<Back to Index>

- Philosopher and Statistician Gottfried Achenwall, 1719

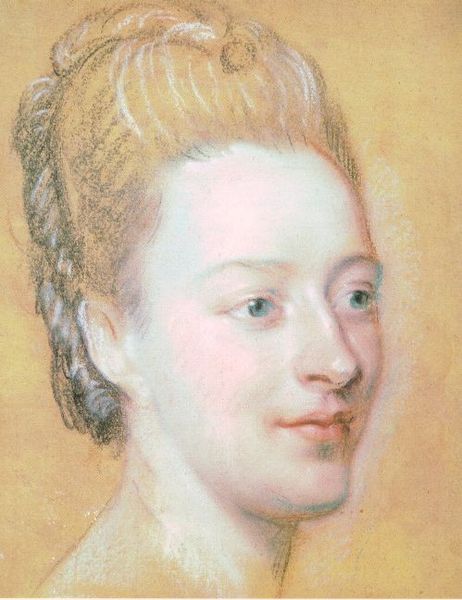

- Writer Isabelle de Charrière (Belle van Zuylen), 1740

- Last Crown Prince of Korea Yi Un (Euimin), 1897

PAGE SPONSOR

Isabelle de Charrière (20 October 1740 – 27 December 1805), known as Belle van Zuylen in the Netherlands and Madame de Charrière elsewhere, is a Dutch writer of the Enlightenment who lived the latter half of her life in Switzerland. She is now best known for her letters although she also wrote novels, pamphlets, music and plays. She took a keen interest in the society and politics of her age, and her work around the time of the French Revolution is regarded as being of particular interest.

Isabella Agneta Elisabeth van Tuyll van Serooskerken was born in Castle Zuylen near Utrecht in the Netherlands, to Diederik Jacob van Tuyll van Serooskerken (1707 - 1776), and Helena Jacoba de Vicq (1724 - 1768). Her parents were described by the British author James Boswell as "one of the most ancient noblemen in the Seven Provinces" and "an Amsterdam lady, with a great deal of money". Isabelle was the eldest of seven children.

In 1750, Isabelle was sent to Geneva and travelled through Switzerland and France. Having spoken only French for a year, she had to relearn Dutch on returning home to the Netherlands. However, French would remain her preferred language for the rest of her life, which helps to explain why, for a long time, her work was not as well known in her country of birth as it otherwise might have been. Isabelle enjoyed a much broader education than was usual for girls at that time, thanks to the liberal views of her parents who also let her study subjects like mathematics. By all accounts, she was a gifted student.

As

she grew older, various suitors appeared on the scene only to be

rejected. She saw marriage as a way to gain freedom but she also wanted

to marry for love. Eventually, in 1771, she married Charles - Emmanuel de

Charrière de Penthaz, the former tutor of her brothers. Since

then she was known as Madame de Charrière. They settled at Le

Pontet in Colombier (near Neuchâtel) in Switzerland. They also spent significant amounts of time in Neuchâtel, Geneva and Paris. Isabelle de Charrière kept up an extensive correspondence with numerous people, including intellectuals like James Boswell and Benjamin Constant. In

1760, Isabelle met David Louis de Constant d'Hermenches (1722 - 1785),

a married Swiss officer regarded in society as a Don Juan. After much

hesitation, Isabelle's need for self - expression overcame her scrupules

and, after a second meeting two years later, she began an intimate and

secret correspondence with him. Constant d'Hermenches was to be one of

her most important correspondents. The Scottish writer James Boswell was

a frequent visitor to Castle Zuylen in 1764 and became a regular

correspondent for several years. After leaving the Netherlands, going on Grand Tour,

he wrote her that he was not in love with her. She replied: "We agree,

because I have no talent for subordination". In 1766 he proposed to her

after meeting her brother in Paris. In 1786, Mme de Charrière met Constant d'Hermenches' nephew, the writer Benjamin Constant in Paris. They began an exchange of letters that would last until the end of her life. Isabelle

de Charrière wrote novels, pamphlets, plays and composed music.

Her most productive period came only after she had been living in

Colombier for a number of years. Themes included her religious doubts,

the nobility and the upbringing of women. Her first novel, Le Noble,

was published in 1762. It was a satire against the nobility and

although it was published anonymously, her identity was soon discovered

and her parents withdrew the work from sale. In 1784 she published two novels, Lettres neuchâteloises and Lettres de Mistriss Henley publiée par son amie.

Both were epistolaries, a form she continued to favour. In 1788, she

published her first pamphlets about the political situation in the

Netherlands. As a admirer of the philosopher Jean - Jacques Rousseau, she assisted in the posthumous publication of his work, Confessions, in 1789. She also wrote her own pamphlets on Rousseau around this time. The French Revolution caused a number of nobles to flee to Neuchâtel and

Mme de Charrière befriended some of them. But she also published

works criticising the attitudes of the aristocratic refugees, most of

whom she felt had learned nothing from the Revolution.