<Back to Index>

- Chemist Johann Friedrich Wilhelm Adolf von Baeyer, 1835

- Painter Henri Regnault, 1843

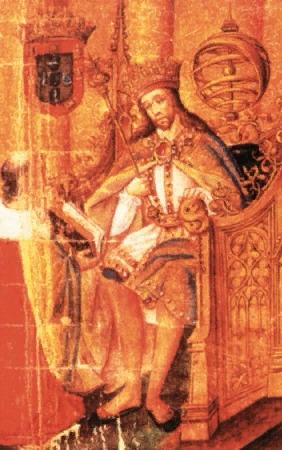

- King of Portugal and the Algarves Edward, the Philosopher, 1391

PAGE SPONSOR

Edward, Portuguese: Duarte (31 October 1391 in Viseu – 9 September 1438 in Tomar), called the Philosopher or the Eloquent, was the eleventh King of Portugal and the Algarve and second Lord of Ceuta from 1433 until his death. He was the son of John I of Portugal and his wife, Philippa of Lancaster, a daughter of John of Gaunt. He was named in honor of his great - grandfather, King Edward III of England. Edward was the oldest member of the Ínclita Geração.

As an infante, Edward always followed his father, King John I, in the affairs of the kingdom. He was knighted in 1415, after the Portuguese capture of the city of Ceuta in North Africa, across from Gibraltar. He became king in 1433 when his father died of the plague and he soon showed interest in internal consensus. During his short reign of five years, Edward called the Cortes (the national assembly) no less than five times to discuss internal affairs and politics. He also followed the politics of his father concerning the maritime exploration of Africa. He encouraged and financed his famous brother, Henry the Navigator, who founded a "school" of maritime navigation at Sagres and who initiated many expeditions. Among these, that of Gil Eanes in 1434 first rounded Cape Bojador on the northwestern coast of Africa, leading the way for further exploration southward along the African coast.

The colony at Ceuta rapidly became a drain on the Portuguese treasury and it was realised that without the city of Tangier, possession of Ceuta was worthless. When Ceuta was captured by the Portuguese, the camel caravans that were part of the overland trade routes began to use Tangier as their new destination. This deprived Ceuta of the materials and goods that made it an attractive market and a vibrant trading locale, and it became an isolated community.

In 1437, Edward's brothers, Henry and Ferdinand, persuaded him to launch an attack on the Marinid sultanate of Morocco. The expedition was not unanimously supported: Infante Peter, Duke of Coimbra and Infante John were both against the initiative; they preferred to avoid conflict with the king of Morocco. They proved to be right. The resulting attack on Tangier, led by Henry, was a debacle. Failing to take the city in a series of assaults, the Portuguese siege camp was soon itself surrounded and starved into submission by a Moroccan relief army. In the resulting treaty, Henry promised to deliver Ceuta back to the Marinids, in return for allowing the Portuguese army to depart unmolested. Edward's youngest brother, Ferdinand the Saint Prince, was handed over to the Marinids as a hostage for the final handover of the city.

The debacle at Tangier dominated Edward's final year. Peter and John urged him to fulfill the treaty, yield Ceuta and secure Ferdinand's release, while Henry (who had signed the treaty) urged him to renege on it. Caught in indecision, Edward assembled the Portuguese Cortes at Leiria in early 1438 for consultation. The Cortes refused to ratify the treaty, preferring to hang on to Ceuta and requesting that Edward find some other way of obtaining Ferdinand's release.

Edward died late that summer of the plague, like his father and mother (and her mother) before him. Popular lore suggested he died of heartbreak over the fate of his hapless brother (Ferdinand would remain in captivity in Fez until his own death in 1443).

Edward's premature death provoked a political crisis in Portugal. Leaving only a young son, Afonso V of Portugal to inherit the throne, it was generally assumed that Edward's brothers would take over the regency of the realm. But Edward's will appointed his unpopular foreign wife, Eleanor of Aragon, as regent. A popular uprising followed, in which the burghers of the realm, assembled by John of Reguengos, acclaimed Peter of Coimbra as regent. But the nobles backed Eleanor's claim, and threatened civil war. The regency crisis was defused by a complicated and tense power sharing arrangement between Eleanor and Peter.

Another less political side of Duarte's personality is related to culture. A reflective and scholarly infante, he wrote the treatises O Leal Conselheiro (The Loyal Counsellor) and Livro Da Ensinanca De Bem Cavalgar Toda Sela (The Art of Riding on Every Saddle) as well as several poems. He was in the process of revising the Portuguese law code when he died.