<Back to Index>

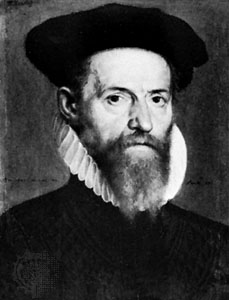

- Physician and Theologian Thomas Erastus, 1524

- Poet Camilo de Almeida Pessanha, 1867

- Prince Esterházy of Galántha Pál I, 1635

PAGE SPONSOR

Thomas Erastus (September 7, 1524 – December 31, 1583) was a Swiss physician and theologian best known for a posthumously published work in which he argued that the sins of Christians should be punished by the state, and not by the church withholding the sacraments. A generalization of this idea, that the state is supreme in church matters, is known somewhat misleadingly as Erastianism.

Erastus was born of poor parents, probably at Baden, Canton of Aargau, Switzerland. His original surname was Lüber, which he translated in humanist style to "Erastus."

In 1540 he was studying arts and theology at Basel. After surviving the plague in 1544, he moved to Bologna as student of philosophy and medicine. In 1553 he became physician to the count of Henneberg, Saxe - Meiningen, and in 1558 held the same post with the elector - palatine, Otto Henry, Elector Palatine, being at the same time professor of medicine at Heidelberg. His patron's successor, Frederick III, made him (1559) a privy councillor and member of the church consistory.

In theology he followed Zwingli, and at the sacramentarian conferences of Heidelberg (1560) and Maulbronn (1564) he advocated by voice and pen the Zwinglian doctrine of the Lord's Supper, replying (1565) to the counter arguments of the Lutheran Johann Marbach, of Strasbourg. He ineffectually resisted the efforts of the Calvinists, led by Caspar Olevianus, to introduce the Presbyterian polity and discipline, which were established at Heidelberg in 1570, on the Genevan model.

One of the first acts of the new church system was to excommunicate Erastus on a charge of Socinianism, founded on his correspondence with Transylvania. The ban was not removed till 1576, Erastus declaring his firm adhesion to the doctrine of the Trinity. His position, however, was uncomfortable, and in 1580 he returned to Basel, where in 1582 he was made professor of ethics. The name of Erastus is known in connection with "Erastianism", used to describe doctrines justifying state control of religion. But the common usage of Erastianism is shown to be a misnomer by the context and detail of the original Treatise of Erastus.

Erastianism, as a by-word, is used to denote the doctrine of the

supremacy of the state in ecclesiastical causes; but the general

problem of the relations between church and state is not one on which

Erastus enters. He published several pieces bearing on medicine, astrology and alchemy, and attacking the system of Paracelsus. In so doing he defended medieval tradition in general, and Galen in particular, while conceding some merit to specific points in Paracelsus. His

name is permanently associated with a posthumous publication, written

in 1568. Its immediate occasion was the disputation at Heidelberg (1568) for the doctorate of theology by George Withers, an English Puritan (subsequently Archdeacon of Colchester), silenced (1565) at Bury St Edmunds by Archbishop Parker. Withers had proposed a disputation against vestments, which the university would not allow; his thesis affirming the excommunicating power of the presbytery was sustained. Hence arose the reply, the Treatise of Erastus. It was published (1589) by Giacomo Castelvetro, who had married his widow. It consists of seventy-five Theses, followed by a Confirmatio in six books, and an appendix of letters to Erastus by Heinrich Bullinger and Rudolf Gwalther, showing that his Theses, written in 1568, had been circulated in manuscript. An English translation of the Theses, with brief life of Erastus (based on Melchior Adam's account), was issued in 1659, entitled The Nullity of Church Censures; it was reprinted as A Treatise of Excommunication (1682), and, as revised by Robert Lee, D.D., in 1844. The

aim of the work is to show, on Scriptural grounds, that sins of

professing Christians are to be punished by civil authority, and not by

withholding of sacraments on the part of the clergy. In the Westminster Assembly a party holding this view included John Selden, John Lightfoot, Thomas Coleman and Bulstrode Whitelocke, whose speech (1645) is appended to Lee's version of the Theses; but the opposite view, after much controversy, was carried, Lightfoot alone dissenting. The consequent chapter of the Westminster Confession of Faith ("Of Church Censures") was, however, not ratified by the English parliament. What is known as Erastianism would be better connected with the name of Hugo Grotius. The only direct reply made to the Explicatio was the Tractatus pius et moderatus de vera excommunicatione et christiano presbyterio (1590) by Theodore Beza, who found himself rather savagely attacked in the Confirmatio thesium; e.g. "Apostolum et Mosen adeoque Deum ipsum audes corrigere."