<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Feng Kang, 1920

- Writer Cesare Pavese, 1908

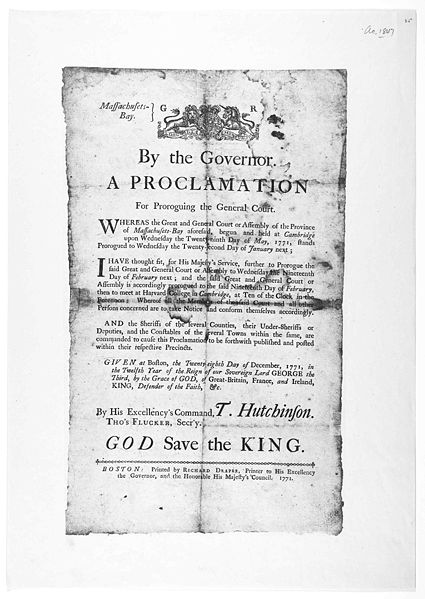

- Governor of the Province of Massachusetts Bay Thomas Hutchinson, 1711

PAGE SPONSOR

Thomas Hutchinson (9 September 1711 – 3 June 1780) was the British royal governor of colonial Massachusetts from 1771 to 1774 and a prominent Loyalist in the years before the American Revolution.

Hutchinson was born in Boston. He showed remarkable aptitude for business early on, and by the time he was 24 had accumulated considerable property in trading ventures on his own account. In 1734 he married Margaret Sanford, a granddaughter of Rhode Island Governor Peleg Sanford; Hutchinson was a great grandson of both Rhode Island Governor William Coddington and of Anne Hutchinson, an early Puritan settler who was banished from the colony for heresy.

As his career advanced he became involved in the civil leadership of the colony, first as a selectman in Boston in 1737. Later in the same year he was chosen a representative to the Massachusetts General Court and at once took a strong stand in opposition to the views of the majority with regard to a proper currency. His unpopular opinions led to his retirement in 1740. In that year he went to England as a commissioner to represent Massachusetts in a boundary dispute with New Hampshire. In 1742 he was re-elected to the General Court, and was chosen annually to the General Court until 1749, serving as the Speaker from 1746 to 1749. He continued his advocacy of a sound currency, and when the British Parliament reimbursed Massachusetts in 1749 for the expenses incurred in the Louisbourg expedition, he proposed the abolition of the bills of credit, and the utilization of the parliamentary repayment as the basis for a new Colonial currency. The proposal was finally adopted by the Assembly, and its good effect on the trade of the colony at once established Hutchinson's reputation as a financier.

On leaving the General Court in 1749 he was appointed at once to the Governor's Council. In 1750 he was chairman of a commission to arrange a treaty with the Indians in the District of Maine, which was then part of Massachusetts, and he served on boundary commissions to settle disputes with Connecticut and Rhode Island. In 1752 he was appointed judge of probate and a justice of the Common Pleas. In 1754, as a delegate from Massachusetts to the Albany Convention, he took a leading part in the discussions and favoured Benjamin Franklin's plan for colonial union.

In 1758 he was appointed lieutenant governor. In 1760 Governor Francis Bernard had appointed Hutchinson instead of James Otis, Sr., as Chief Justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court. In the following year, by issuing writs of assistance, he brought upon himself a storm of protest and criticism. His distrust of popular government as exemplified in the New England town meeting increased. Although he opposed the principle of the Stamp Act,

considered it impolitic, and later advised its repeal, he accepted its

legality, and, as a result of his stand, his city house was ransacked

by a mob in August 1765, and his valuable collection of books was

destroyed. For many years he had been working on a history of the

colony, compiling original manuscripts and source materials. After the

destruction of his home, he bitterly rescued many of these materials from the muddy road. In 1769, upon the resignation of Governor Francis Bernard, he became acting governor, serving in that capacity at the time of the Boston Massacre, 5 March 1770, when popular clamour compelled him to order the removal of the troops from the city. In

March 1771, he received his commission as governor, and was the last

civilian governor of the Massachusetts colony. His administration,

controlled completely by the British ministry, increased the friction

with the colonials. The publication, in 1773, of some letters on colonial affairs written

by Hutchinson, and obtained by Franklin in England, still further

aroused public indignation. In England, while Hutchinson was vindicated

in discussions in the Privy Council,

Franklin was severely criticised and fired as a colonial postmaster

general. The resistance of the colonials led the ministry to see the

necessity for stronger measures. A temporary suspension of the civil

government followed, and General Gage was appointed military governor in April 1774. Driven

from the country by threats in the following May and broken in health

and spirit, Hutchinson spent the rest of his life in exile in England. In England, still nominally governor, he was consulted by Lord North in regard to American affairs; but his advice that a moderate policy be adopted, and his opposition to the Boston Port Bill, and the suspension of the Massachusetts charter, were not heeded. While

he was still officially the acting governor, he was compelled to refuse

a baronetcy because of the severe financial losses when his American

estates and other property in Massachusetts were confiscated by the new

government without compensation by the Crown. Bitter and disillusioned,

Hutchinson, nevertheless, continued to work on his history of the

colony which was the fruit of many decades of research. Two volumes

were published in his lifetime. His History of Massachusetts Bay (volume

i, 1764; volume ii, 1767; volume iii, 1828) a work of great historical

value, calm, and judicious in the main, but considered by some to be entirely unphilosophical and lacking in style. His Diary and Letters was published in 1884 – 86. He died at Brompton, now a part of London, on 3 June 1780, aged 68. Hutchinson had built a country estate in Milton, Massachusetts, part of which, Governor Hutchinson's Field is owned by The Trustees of the Reservations and is open to the public. He built a garden behind the house, which is now listed on the National Register of Historic Places.