<Back to Index>

- Philosopher Hans Vaihinger, 1852

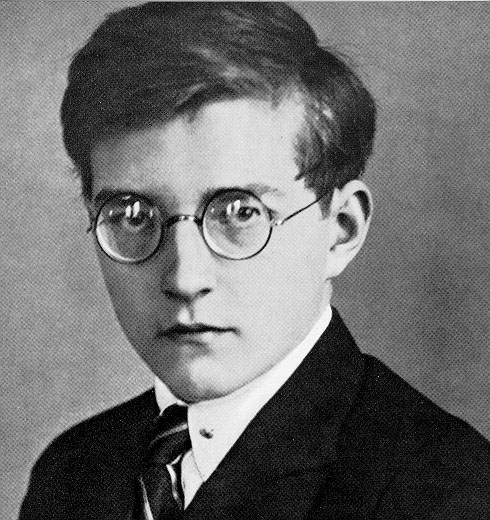

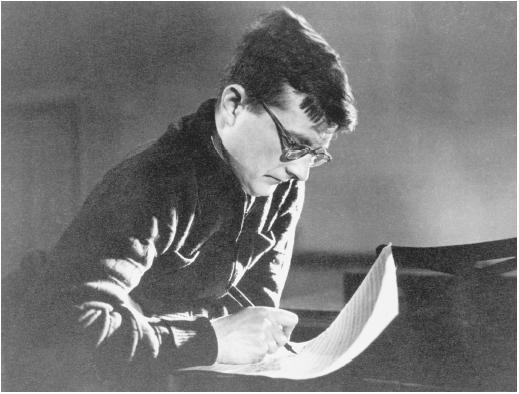

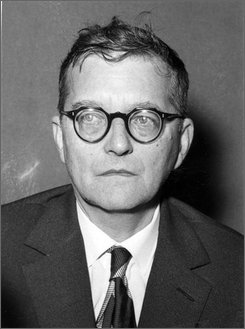

- Composer Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich, 1906

- 7th President of Italy Alessandro (Sandro) Pertini, 1896

PAGE SPONSOR

Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich (September 1906 — 9 August 1975) was a Soviet Russian composer and one of the most celebrated composers of the 20th century.

Shostakovich achieved fame in the Soviet Union under the patronage of Leon Trotsky's chief of staff Mikhail Tukhachevsky, but later had a complex and difficult relationship with the Stalinist bureaucracy. In 1936, the government, most probably under orders from Stalin, harshly criticized his opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District, causing him to withdraw the Fourth Symphony during its rehearsal stages. Shostakovich's music was officially denounced twice, in 1936 and 1948, and was periodically banned. Nevertheless, he also received accolades and state awards and served in the Supreme Soviet of the RSFSR. Despite the official controversy, his works were popular and well received.

After a period influenced by Sergei Prokofiev and Igor Stravinsky, Shostakovich developed a hybrid style, as exemplified by Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District (1934). This single work juxtaposed a wide variety of trends, including the neo - classical style (showing the influence of Stravinsky) and post - Romanticism (after Gustav Mahler). Sharp contrasts and elements of the grotesque characterize much of his music.

Shostakovich's orchestral works include 15 symphonies and six concerti. His symphonic work is typically complex and requires large scale orchestras. Music for chamber ensembles includes 15 string quartets,

a piano quintet, two pieces for a string octet, and two piano trios.

For the piano he composed two solo sonatas, an early set of preludes, and a later set of 24 preludes and fugues. Other works include two operas, and a substantial quantity of film music. Born at 2 Podolskaya Ulitsa in Saint Petersburg, Russia,

Shostakovich was the second of three children born to Dmitri

Boleslavovich Shostakovich and Sofiya Vasilievna Kokoulina.

Shostakovich's paternal grandfather (originally surnamed Szostakowicz) was of Polish Roman Catholic descent (his family roots trace to the region of the town of Vileyka in Belarus), but his immediate forebears came from Siberia. His paternal grandfather, a Polish revolutionary in the January Uprising of 1863–4, had been exiled to Narim (near Tomsk) in 1866 in the crackdown that followed Dmitri Karakozov's assassination attempt on Tsar Alexander II. When his term of exile ended, Boleslaw Szostakowicz decided to remain in Siberia. He eventually became a successful banker in Irkutsk and

raised a large family. His son, Dmitriy Boleslavovich Shostakovich, the

composer's father, was born in exile in Narim in 1875 and attended Saint Petersburg University,

graduating in 1899 from the faculty of physics and mathematics. After

graduation, Dmitriy Boleslavovich went to work as an engineer under Dmitriy Mendeleyev at

the Bureau of Weights and Measures in Saint Petersburg. In 1903, he

married Sofiya Vasilievna Kokoulina, another Siberian transplant to the

capital. Sofiya herself was one of six children born to Vasiliy Yakovlevich Kokoulin, a Russian Siberian native. Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich was a child prodigy as

a pianist and composer, his talent becoming apparent after he began

piano lessons with his mother at the age of eight. (On several

occasions, he displayed a remarkable ability to remember what his

mother had played at the previous lesson, and would get "caught in the

act" of pretending to read, playing the previous lesson's music when

different music was placed in front of him.) In 1918, he wrote a funeral march in memory of two leaders of the Kadet party, murdered by Bolshevik sailors. In 1919, at the age of 13, he was allowed to enter the Petrograd Conservatory, then headed by Alexander Glazunov. Glazunov monitored Shostakovich's progress closely and promoted him. Shostakovich studied piano with Leonid Nikolayev, after a year in the class of Elena Rozanova, composition with Maximilian Steinberg, and counterpoint and fugue with Nikolay Sokolov, with whom he became friends. Shostakovich also attended Alexander Ossovsky's history of music classes. However, he suffered for his perceived lack of political zeal, and initially failed his exam in Marxist methodology in 1926. His first major musical achievement was the First Symphony (premiered 1926), written as his graduation piece at the age of nineteen. After

graduation, he initially embarked on a dual career as concert pianist

and composer, but his dry style of playing (Fay comments on his

"emotional restraint" and "riveting rhythmic drive") was often

unappreciated. He nevertheless won an "honorable mention" at the First International Frederic Chopin Piano Competition in Warsaw in 1927. After the competition Shostakovich met the conductor Bruno Walter, who was so impressed by the composer's First Symphony that he conducted it at its Berlin premiere later that year. Leopold Stokowski was equally impressed and gave the work its U.S. Premiere the following year and also made the work's first recording. Thereafter,

Shostakovich concentrated on composition and soon limited performances

primarily to those of his own works. In 1927 he wrote his Second Symphony (subtitled To October). While writing the symphony, he also began his satirical opera The Nose, based on the story by Gogol. In 1929, the opera was criticised as "formalist" by RAPM, the Stalinist musicians' organisation, and it opened to generally poor reviews in 1930. 1927 also marked the beginning of the composer's relationship with Ivan Sollertinsky, who remained his closest friend until the latter's death in 1944. Sollertinsky introduced Shostakovich to the music of Gustav Mahler, which had a strong influence on his music from the Fourth Symphony onwards.

In 1932, he married his first wife, Nina Varzar. Initial difficulties

led to a divorce in 1935, but the couple soon remarried when Nina

became pregnant with their first child. In the late 1920s and early 1930s he worked at TRAM,

a proletarian youth theatre. Although he did little work in this post,

it shielded him from ideological attack. Much of this period was spent

writing his opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District;

it was first performed in 1934 and was immediately successful, both on

a popular and official level. It was described as, "the result of the

general success of Socialist construction, of the correct policy of the

Party" and said that such an opera “could have been written only by a

Soviet composer brought up in the best tradition of Soviet culture.”

In 1936 Shostakovich fell from official favour. The year began with a series of attacks on him in

Pravda, in particular an article entitled Muddle Instead of Music. Shostakovich was away on a concert tour in Arkhangel’sk when he heard news of the Pravda article.

Two days before the article was published on the evening of January

26th, a friend advised Shostakovich to attend the Bolshoi Theatre

production of his opera. When he arrived, he saw that Stalin and the

Politburo were there. In letters written to Ivan Sollertinsky, a close

friend and advisor, Shostakovich recounts the horror with which he

watched as Stalin shuddered every time the brass and percussion played

too loudly. Equally horrifying was the way Stalin and his companions

laughed at the love making scene between Sergei and Katerina.

Eyewitness accounts testify that Shostakovich was “white as a sheet”

when he went to take his bow after the third act. The article, which condemned Lady Macbeth as formalist, "coarse, primitive and vulgar," was thought to have been instigated by Stalin;

consequently, commissions began to fall off, and his income fell by

about three quarters. Even Soviet music critics who had praised the

opera were forced to recant in print, saying they "failed to detect the

shortcomings of Lady Macbeth as pointed out by the Pravda. Shortly

after the “Muddle Instead of Music” article, Pravda published another,

“Ballet Falsehood,” that criticized Shostakovich’s ballet The Limpid Stream.

Shostakovich did not expect this second article because the general

public and press already accepted this music as “democratic,” or

tuneful and accessible. However, Pravda criticized The Limpid Stream for

incorrectly displaying peasant life on the collective farm. According

to the authorities, the reality of the collective farm was too serious a theme to be displayed in an opera. Between

the Fourth and Fifth symphonies during the years of 1936 and 1937,

Shostakovich mainly composed film music in order to remain in Stalin’s

favor. Stalin recognized that the popularity of Shostakovich’s music

was useful as a propaganda tool, and therefore allowed him to continue

composing. A

public denunciation from the main party newspaper equaled a death

sentence. This naturally put Shostakovich in a state of high anxiety as

he attempted to write the Fourth Symphony. Rehearsal of the Fourth Symphony began

that December, but the political climate made performance impossible.

It was not performed until 1961, but Shostakovich did not repudiate the

work: it retained its designation as his Fourth Symphony. A piano

reduction was published in 1946. More widely, 1936 marked the beginning of the Great Terror, in which many of the composer's friends and relatives were imprisoned or killed. His only consolation in this period was the birth of his daughter Galina in 1936; his son Maxim was born two years later. The composer's response to his denunciation was the Fifth Symphony of

1937, which was, because of its fourth movement, musically more

conservative than his earlier works. Premiering on November 21st, 1937

in Leningrad, it was immensely popular and the success put Shostakovich

in good standing once again. Even the authorities accepted it, and soon

the piece was commissioned to be a part of the celebrations for the

Twentieth Anniversary of the Revolution. Those

who had earlier criticized Shostakovich of formalism claimed that he

had learned from his mistakes and had become a true Soviet artist. For

example, fellow composer Dmitry Kabalevsky, who was among those who

disassociated himself from Shostakovich when the Pravda article

was published, praised the Fifth Symphony and congratulated

Shostakovich for “not having given into the seductive temptations of

his previous ‘erroneous’ ways.” It was also at this time that Shostakovich composed the first of his string quartets. His chamber works

allowed him to experiment and express ideas which would have been

unacceptable in his more public symphonic pieces. In September 1937, he

began to teach composition at the Conservatory, which provided some

financial security but interfered with his own creative work. In 1939, before the Soviet forces invaded Finland, the Party Secretary of Leningrad Andrei Zhdanov commissioned a celebratory piece from Shostakovich, entitled Suite on Finnish Themes to be performed as the marching bands of the Red Army would be parading through the Finnish capital Helsinki. The Winter War was a humiliation for the Red Army, and Shostakovich would never lay claim to the authorship of this work. It was not performed until 2001. After the outbreak of war between the Soviet Union and Germany in

1941, Shostakovich initially remained in Leningrad. He tried to enlist

for the military but was turned away because he had bad eyesight. To

compensate, Shostakovich became a volunteer for the Leningrad

Conservatory’s firefighter brigade and delivered a radio broadcast to

the Soviet people. He

even posed for a photograph that was published in newspapers throughout

the country as a symbol of propaganda for Leningrader’s support for the

war. By

far his greatest and most famous wartime contribution during this time

was the Seventh Symphony. Shostakovich wrote the first three movements

in Leningrad, and completed the work in Kuibyshev, now a settlement in

Volgograd Oblast, where he and his family was evacuated. There is a lot

of controversy concerning whether or not Shostakovich really conceived

the idea of the Seventh Symphony with the siege of Leningrad in mind.

Whether he did or not, the Seventh Symphony became the representation

of Leningrader’s brave resistance to the German invaders. The Seventh

Symphony was immensely popular because its audience saw it as an

authentic piece of patriotic art in a time when people’s morals needed

boosting. The Seventh Symphony was first premiered at the Bolshoi

Theatre in Moscow, and was soon performed abroad in London and the

United States. However, the most compelling performance took place in

besieged Leningrad by the Radio Orchestra. The orchestra only had

fourteen musicians left, so the conductor Karl Eliasberg had to recruit

anyone who could play a musical instrument to perform the symphony.

This incredible feat represented the city’s courage to keep up.

In

spring 1943 the family moved to Moscow. At the time of the Eighth

Symphony's premier, the Red Army began winning the war. Therefore the

public, and most importantly the authorities, wanted another triumphant

piece from the composer. Instead, they got the Eighth Symphony. While

the Seventh Symphony depicts a heroic (and ultimately victorious)

struggle against adversity, the

Eighth Symphony of

that year is perhaps the ultimate in sombre and violent expression

within Shostakovich's output, resulting in it being banned until 1956.

The Ninth Symphony (1945),

in contrast, is an ironic Haydnesque parody, which failed to satisfy

demands for a "hymn of victory." The war was won, and unfortunately

Shostakovich’s “pretty” symphony was interpreted as a mockery of the

Soviet Union’s victory rather than a celebratory piece. Shostakovich

continued to compose chamber music, notably his Second Piano Trio (Op. 67), dedicated to the memory of Sollertinsky, with a bitter - sweet, Jewish themed totentanz finale. In 1948 Shostakovich, along with many other composers, was again denounced for formalism in the Zhdanov decree.

Andrei Zhnadov, Chairman of the RSFSR Supreme Soviet, teamed up with

the General Secretary of the Composer’s Union, Tikhon Khrennikov, to

accuse Shostakovich and other composers (such as Sergei Prokofiev and

Dmitry Kabalevsky) for writing inappropriate and formalist music. The

conference resulted in the publication of the Central Committee’s

Decree “On V. Muradeli’s opera The Great Friendship,”

which was targeted towards all Soviet composers and demanded that they

only write “proletarian” music, or music for the masses. The accused

composers, including Shostakovich, were summoned to make public

apologies in front of the committee. Most of Shostakovich's works were banned, he was forced to publicly repent, and his family had privileges withdrawn. Yuri Lyubimov says

that at this time "he waited for his arrest at night out on the landing

by the lift, so that at least his family wouldn't be disturbed." The

consequences of the decree for composers were harsh. Shostakovich was

among those who were dismissed from the Conservatoire altogether. For

Shostakovich, the loss of money was perhaps the largest blow. Others

still in the Conservatory experienced an atmosphere that was thick with

suspicion. No one wanted their work to be understood as formalist, so

many resorted to accusing their colleagues of writing or performing

anti - proletarian music. In the next few years his compositions were divided into film music to pay the rent, official works aimed at securing official rehabilitation, and serious works "for the desk drawer". The latter included the Violin Concerto No. 1 and the song cycle From Jewish Folk Poetry. The cycle was written at a time when the post-war anti - Semitic campaign was already under way, and Shostakovich had close ties with some of those affected. The

restrictions on Shostakovich's music and living arrangements were eased

in 1949, to secure his participation in a delegation of Soviet notables

to the U.S. That year he also wrote his cantata Song of the Forests, which praised Stalin as the "great gardener." In 1951 the composer was made a deputy to the Supreme Soviet of RSFSR. Stalin's death in 1953 was the biggest step towards Shostakovich's official rehabilitation, which was marked by his Tenth Symphony. It features a number of musical quotations and codes (notably the DSCH and

Elmira motifs), the meaning of which is still debated, whilst the

savage second movement is said to be a musical portrait of Stalin

himself. It ranks alongside the Fifth and Seventh as one of his most

popular works. 1953 also saw a stream of premieres of the "desk drawer"

works. During the forties and fifties Shostakovich had close relationships with two of his pupils: Galina Ustvolskaya and Elmira Nazirova. He taught Ustvolskaya from 1937 to 1947. The nature of their relationship is far from clear: Mstislav Rostropovich described it as "tender" and Ustvolskaya claimed in a 1995 interview that

she rejected a proposal of marriage from him in the fifties. However,

in the same interview, Ustvolskaya's friend, Viktor Suslin, said that

she had been "deeply disappointed" in him by the time of her graduation

in 1947. The relationship with Nazirova seems to have been one sided,

expressed largely through his letters to her, and can be dated to

around 1953 to 1956. In the background to all this remained

Shostakovich's first, open marriage to Nina Varzar until her death in

1954. He married his second wife, Komsomol activist Margarita Kainova, in 1956; the couple proved ill matched, and divorced three years later. In 1954, Shostakovich wrote the Festive Overture, opus 96, that was used as the theme music for the 1980 Summer Olympics. In addition his '"Theme from the film Pirogov, Opus 76a: Finale" was played as the cauldron was lit at the 2004 Summer Olympics in Athens, Greece. In 1959, Shostakovich appeared on stage in Moscow at the end of a concert performance of his Fifth Symphony, congratulating Leonard Bernstein and the New York Philharmonic Orchestra for

their performance (part of a concert tour of the Soviet Union).

Bernstein recorded the symphony later that year in New York for Columbia Records.

Even

before the Stalinist anti - Semitic campaigns in the late 1940s and early

1950s, Shostakovich showed an interest in Jewish themes. He was

intrigued by Jewish music’s “ability to build a jolly melody on sad

intonations.” Examples

of works that included Jewish themes are the Fourth String Quartet

(1949), the First Violin Concerto (1948), and the Four Monologues on

Pushkin Poems (1952). He was further inspired to write with Jewish

themes when he examined Moiser Beregovsky’s thesis on the theme of

Jewish folk music in 1946. In 1948 Shostakovich acquired a book of

Jewish folk songs, and from this he composed the song cycle From Jewish Poetry.

He initially wrote eight songs that were meant to represent the

hardships of being Jewish in the Soviet Union. However in order to

disguise this, Shostakovich ended up adding three more songs meant to

demonstrate the great life Jews had under the Soviet regime. Despite

his efforts to hide the real meaning in the work, the Union of

Composers refused to approve his music in 1949 under the pressure of

the anti - Semitism that gripped the country. From Jewish Poetry could not be performed until after Stalin’s death in March 1953, along with all the other works that were forbidden.

The year 1960 marked another turning point in Shostakovich's life: his joining of the

Communist Party.

The government wanted to appoint him General Secretary of the

Composer’s Union, but in order to hold that position Shostakovich was

required to attain Party membership. It was understood that Nikita

Khrushchev, the First Secretary of the Communist Party from 1958 to

1964, was looking for support from the leading ranks of the

intelligentsia in an effort to create a better relationship with the

Soviet Union’s artists. This

event has been interpreted variously as a show of commitment, a mark of

cowardice, the result of political pressure, and as his free decision. On the one hand, the apparat was

undoubtedly less repressive than it had been before Stalin's death. On

the other, his son recalled that the event reduced Shostakovich to

tears, and he later told his wife Irina that he had been blackmailed. Lev Lebedinsky has said that the composer was suicidal. Once he joined the Party, several articles denouncing individualism in music were published in Pravda under

his name, though he did not actually write them. In addition, in

joining the party, Shostakovich was also committing himself to finally

writing the homage to Lenin that he had promised before. His Twelfth

Symphony, which portrays the Bolshevik Revolution and was completed in

1961, was dedicated to Vladimir Lenin and called “The Year 1917.” Around this time, his health also began to deteriorate. Shostakovich's musical response to these personal crises was the Eighth String Quartet,

composed in only three days. The Eighth String Quartet was written for

the survivors of the Dresden fire bombing that took place in 1945.

Shostakovich subtitled the piece, "In Memory of the Nazi and War

Victims." Like the Tenth Symphony, this quartet incorporates quotations and his musical monogram. In

1962 he married for the third time, to Irina Supinskaya. In a letter to

his friend Isaak Glikman, he wrote, "her only defect is that she is 27

years old. In all other respects she is splendid: clever, cheerful,

straightforward and very likeable." According to Galina Vishnevskaya, who knew the Shostakoviches well, this marriage was a very happy one:

"It was with her that Dmitri Dmitriyevich finally came to know domestic

peace... Surely, she prolonged his life by several years." In November Shostakovich made his only venture into conducting, conducting a couple of his own works in Gorky: otherwise he declined to conduct, citing nerves and ill health as his reasons. That year saw Shostakovich again turn to the subject of anti - Semitism in his Thirteenth Symphony (subtitled Babi Yar). The symphony sets a number of poems by Yevgeny Yevtushenko,

the first of which commemorates a massacre of the Jews during the

Second World War. Opinions are divided how great a risk this was: the

poem had been published in Soviet media, and was not banned, but it

remained controversial. After the symphony's premiere, Yevtushenko was

forced to add a stanza to his poem which said that Russians and

Ukrainians had died alongside the Jews at Babi Yar. In 1965 Shostakovich raised his voice in defense of poet Joseph Brodsky,

who was sentenced to five years of exile and hard labor. Shostakovich

co-signed protests together with Yevtushenko and fellow Soviet artists Kornei Chukovsky, Anna Akhmatova, Samuil Marshak, and the French philosopher Jean - Paul Sartre.

After the protests the sentence was commuted, and Brodsky returned to

Leningrad. Shostakovich joined the group of 25 distinguished

intellectuals in signing the letter to Leonid Brezhnev asking not to rehabilitate Stalin. In later life, Shostakovich suffered from chronic ill health, but he resisted giving up cigarettes and vodka.

Beginning in 1958 he suffered from a debilitating condition that

particularly affected his right hand, eventually forcing him to give up

piano playing; in 1965 it was diagnosed as polio. He also suffered heart attacks the following year and again in 1971, and several falls in which he broke both his legs; in 1967 he wrote in a letter: "Target

achieved so far: 75% (right leg broken, left leg broken, right hand

defective). All I need to do now is wreck the left hand and then 100%

of my extremities will be out of order." A preoccupation with his own mortality permeates Shostakovich's later works, among them the later quartets and the Fourteenth Symphony of

1969 (a song cycle based on a number of poems on the theme of death).

This piece also finds Shostakovich at his most extreme with musical

language, with twelve - tone themes and dense polyphony used throughout.

Shostakovich dedicated this score to his close friend Benjamin Britten, who conducted its Western premiere at the 1970 Aldeburgh Festival. The Fifteenth Symphony of 1971 is, by contrast, melodic and retrospective in nature, quoting Wagner, Rossini and the composer's own Fourth Symphony. Shostakovich died of lung cancer on 9 August 1975 and after a civic funeral was interred in the Novodevichy Cemetery, Moscow. The official obituary did not appear in Pravda until three days after his death, apparently because the wording had to be approved at the highest level, by Leonid Brezhnev and the rest of the Politburo. Even before his death he had been commemorated with the naming of the Shostakovich Peninsula on Alexander Island, Antarctica. He was survived by his third wife, Irina; his daughter, Galina; and his son, Maxim,

a pianist and conductor who was the dedicatee and first performer of

some of his father's works. Shostakovich himself left behind several

recordings of his own piano works, while other noted interpreters of

his music include his friends Emil Gilels, Mstislav Rostropovich, Tatiana Nikolayeva, Maria Yudina, David Oistrakh, and members of the Beethoven Quartet. Shostakovich's opera Orango (1932) was found by Russian researcher Olga Digonskaya in his last home. It is being orchestrated by the British composer Gerard McBurney and will be performed some time in 2010 – 2011. Shostakovich's musical influence on later composers outside the former Soviet Union has been relatively slight, although Alfred Schnittke took up his eclecticism, and his contrasts between the dynamic and the static, and some of André Previn's

music shows clear links to Shostakovich's style of orchestration. His

influence can also be seen in some Nordic composers, such as Kalevi Aho and Lars - Erik Larsson. Many of his Russian contemporaries, and his pupils at the Leningrad Conservatory, however, were strongly influenced by his style (including German Okunev, Boris Tishchenko, whose 5th Symphony of 1978 is dedicated to Shostakovich's memory, Sergei Slonimsky,

and others). Shostakovich's conservative idiom has nonetheless grown

increasingly popular with audiences both within and beyond Russia, as

the avant - garde has declined in influence and debate about his

political views has developed. Shostakovich's works are broadly tonal and in the Romantic tradition, but with elements of atonality and chromaticism. In some of his later works (e.g., the Twelfth Quartet), he made use of tone rows.

His output is dominated by his cycles of symphonies and string

quartets, each numbering fifteen. The symphonies are distributed fairly

evenly throughout his career, while the quartets are concentrated

towards the latter part. Among the most popular are the Fifth and Seventh Symphonies and the Eighth and Fifteenth Quartets. Other works include the operas Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, The Nose and the unfinished The Gamblers based on the comedy of Nikolai Gogol; six concertos (two each for piano, violin and cello); two piano trios; and a large quantity of film music. Shostakovich's music shows the influence of many of the composers he most admired: Bach in his fugues and passacaglias; Beethoven in the late quartets; Mahler in the symphonies and Berg in his use of musical codes and quotations. Among Russian composers, he particularly admired Modest Mussorgsky, whose operas Boris Godunov and Khovanshchina he re-orchestrated; Mussorgsky's influence is most prominent in the wintry scenes of Lady Macbeth and the Eleventh Symphony, as well as in his satirical works such as "Rayok". Prokofiev's influence is most apparent in the earlier piano works, such as the first sonata and first concerto. The influence of Russian church and folk music is very evident in his works for unaccompanied choir of the 1950s. Shostakovich's relationship with Stravinsky was profoundly ambivalent; as he wrote to Glikman, "Stravinsky the composer I worship. Stravinsky the thinker I despise." He was particularly enamoured of the Symphony of Psalms,

presenting a copy of his own piano version of it to Stravinsky when the

latter visited the USSR in 1962. (The meeting of the two composers was

not very successful, however; observers commented on Shostakovich's

extreme nervousness and Stravinsky's "cruelty" to him.) Many

commentators have noted the disjunction between the experimental works

before the 1936 denunciation and the more conservative ones that

followed; the composer told Flora Litvinova, "without 'Party

guidance' ... I would have displayed more brilliance, used more

sarcasm, I could have revealed my ideas openly instead of having to

resort to camouflage." Articles published by Shostakovich in 1934 and 1935 cited Berg, Schoenberg, Krenek, Hindemith, "and especially Stravinsky" among his influences. Key works of the earlier period are the First Symphony, which combined the academicism of the conservatory with his progressive inclinations; The Nose ("The most uncompromisingly modernist of all his stage works"); Lady Macbeth. which precipitated the denunciation; and the Fourth Symphony, described by Grove as "a colossal synthesis of Shostakovich's musical development to date". The

Fourth Symphony was also the first in which the influence of Mahler

came to the fore, prefiguring the route Shostakovich was to take to

secure his rehabilitation, while he himself admitted that the preceding

two were his least successful. In

the years after 1936, Shostakovich's symphonic works were outwardly

musically conservative, regardless of any subversive political content.

During this time he turned increasingly to chamber works, a field that permitted the composer to explore different and often darker ideas without inviting external scrutiny. While

his chamber works were largely tonal, they gave Shostakovich an outlet

for sombre reflection not welcomed in his more public works. This is

most apparent in the late chamber works, which portray what Groves has

described as a "world of purgatorial numbness"; in some of these he included the use of tone rows, although he treated these as melodic themes rather than serially. Vocal works are also a prominent feature of his late output, setting texts often concerned with love, death and art. According

to Shostakovich scholar Gerard McBurney, opinion is divided on whether

his music is "of visionary power and originality, as some maintain, or,

as others think, derivative, trashy, empty and second - hand." William Walton, his British contemporary, described him as "The greatest composer of the 20th century." Musicologist David Fanning concludes in Grove that,

"Amid the conflicting pressures of official requirements, the mass

suffering of his fellow countrymen, and his personal ideals of

humanitarian and public service, he succeeded in forging a musical

language of colossal emotional power." Some modern composers have been critical. Pierre Boulez dismissed Shostakovich's music as "the second, or even third pressing of Mahler." The Romanian composer and Webern disciple Philip Gershkovich called Shostakovich "a hack in a trance." A related complaint is that Shostakovich's style is vulgar and strident: Stravinsky wrote of Lady Macbeth: "brutally hammering ... and monotonous." English composer and musicologist Robin Holloway described

his music as "battleship - grey in melody and harmony, factory - functional

in structure; in content all rhetoric and coercion." In the 1980s, the Finnish conductor and composer Esa - Pekka Salonen was critical of Shostakovich and didn't conduct his music. For instance, he said in 1987: "Shostakovich

is in many ways a polar counter - force for Stravinsky. [...] When I have

said that the 7th symphony of Shostakovich is a dull and unpleasant

composition, people have responded: 'Yes, yes, but think of the

background of that symphony.' Such an attitude does no good to anyone." It is certainly true that Shostakovich borrows extensively from the material and styles both of earlier composers and of popular music; the vulgarity of "low" music is a notable influence on this "greatest of eclectics". McBurney traces this to the avant - garde artistic

circles of the early Soviet period in which Shostakovich moved early in

his career, and argues that these borrowings were a deliberate

technique to allow him to create "patterns of contrast, repetition,

exaggeration" that gave his music the large scale structure it required.

Shostakovich was in many ways an obsessive man: according to his daughter he was "obsessed with cleanliness"; he synchronised the clocks in his apartment; he regularly sent cards to himself to test how well the postal service was working. Elizabeth Wilson's Shostakovich: A Life Remembered (1994) indexes 26 references to his nervousness. Mikhail Druskin

remembers that even as a young man the composer was "fragile and

nervously agile". Yuri

Lyubimov comments, "The fact that he was more vulnerable and receptive

than other people was no doubt an important feature of his genius". In later life, Krzysztof Meyer recalled, "his face was a bag of tics and grimaces". In

his lighter moods, sport was one of his main recreations, although he

preferred spectating or umpiring to participating (he was a qualified football referee). His favourite football club was Zenit Leningrad, which he would watch regularly. He also enjoyed playing card games, particularly patience. Both light and dark sides of his character were evident in his fondness for satirical writers such as Gogol, Chekhov and Mikhail Zoshchenko. The influence of the latter in particular is evident in his letters, which include wry parodies of Soviet officialese.

Zoshchenko himself noted the contradictions in the composer's

character: "he is ... frail, fragile, withdrawn, an infinitely

direct, pure child ... [but he is also] hard, acid, extremely

intelligent, strong perhaps, despotic and not altogether good natured

(although cerebrally good natured)". He was diffident by nature: Flora Litvinova has said he was "completely incapable of saying 'No' to anybody." This meant he was easily persuaded to sign official statements, including a denunciation of Andrei Sakharov in

1973; on the other hand he was willing to try to help constituents in

his capacities as chairman of the Composers' Union and Deputy to the

Supreme Soviet. Oleg Prokofiev commented that "he tried to help so many people that ... less and less attention was paid to his pleas." Shostakovich was an agnostic and stated when asked if he believed in God, "No, and I am very sorry about it."

Shostakovich's

response to official criticism and, what is more important, the

question of whether he used music as a kind of abstract dissidence is a

matter of dispute. He outwardly conformed to government policies and

positions, reading speeches and putting his name to articles expressing

the government line.

But it is evident he disliked many aspects of the regime, as confirmed

by his family, his letters to Isaak Glikman, and the satirical cantata "Rayok", which ridiculed the "anti - formalist" campaign and was kept hidden until after his death. He was a close friend of Marshal of the Soviet Union Mikhail Tukhachevsky, who was executed in 1937 during the Great Purge. It is also uncertain to what extent Shostakovich expressed his opposition to the state in his music. The revisionist view was put forth by Solomon Volkov in the 1979 book Testimony,

which was claimed to be Shostakovich's memoirs dictated to Volkov. The

book alleged that many of the composer's works contained coded

anti - government messages.

That would place Shostakovich in a tradition of Russian artists

outwitting censorship that goes back at least to the early 19th century

poet Pushkin. It is known that he incorporated many quotations and motifs in his work, most notably his signature DSCH theme. His longtime collaborator Evgeny Mravinsky said that "Shostakovich very often explained his intentions with very specific images and connotations." The revisionist perspective has subsequently been supported by his children, Maxim and Galina, and many Russian musicians. More recently, Volkov has argued that Shostakovich adopted the role of the yurodivy or holy fool in

his relations with the government. Shostakovich's widow Irina, who was

present during Volkov's visits to Shostakovich, denies the authenticity

of Testimony. Other prominent revisionists are Ian MacDonald, whose book The New Shostakovich put forward more interpretations of his music, and Elizabeth Wilson, whose Shostakovich: A Life Remembered provides testimony from many of the composer's acquaintances.

In May 1958, during a visit to Paris, Shostakovich recorded his two piano concertos with André Cluytens, as well as some short piano works. These were issued by EMI on an LP, reissued by Seraphim Records on LP, and eventually digitally remastered and released on CD. Shostakovich recorded the two concertos in stereo in Moscow for Melodiya. Shostakovich also played the piano solos in recordings of the Sonata, Op. 40, for Cello and Piano with cellist Daniil Shafran and also with Mstislav Rostropovich; the Sonata, Op. 134, for Violin and Piano with violinist David Oistrakh; and the Trio, Op. 67, for Violin, Cello, and Piano with violinist David Oistrakh and cellist Miloš Sádlo.

There is also a short sound film of Shostakovich as soloist in a 1930s

concert performance of the closing moments of his first piano concerto.

A color film of Shostakovich supervising one of his operas, from his

last year, was also made.

Musicians and scholars including Laurel Fay and Richard Taruskin contest the authenticity and debate the significance of Testimony, alleging that Volkov compiled it from a combination of recycled

articles, gossip, and possibly some information direct from the

composer. Fay documents these allegations in her 2002 article 'Volkov's Testimony reconsidered', showing that the only pages of the original Testimony manuscript

that Shostakovich had signed and verified are word - for - word

reproductions of earlier interviews given by the composer, none of

which are controversial. (Against this, it has been pointed out by

Allan B. Ho and Dmitry Feofanov that

at least two of the signed pages contain controversial material: for

instance, "on the first page of chapter 3, where [Shostakovich] notes

that the plaque that reads 'In this house lived [Vsevolod] Meyerhold' should also say 'And in this house his wife was brutally murdered'.") More broadly, Fay and Taruskin argue that

the significance of Shostakovich is in his music rather than his life,

and that to seek political messages in the music detracts from, rather

than enhances, its artistic value.