<Back to Index>

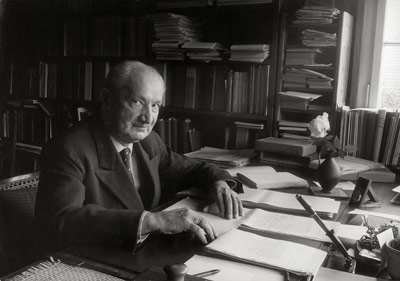

- Philosopher Martin Heidegger, 1889

- Composer Wenzel Müller, 1767

- Prime Minister of Portugal Fernando de Sá Nogueira de Figueiredo, 1st Marquess de Sá da Bandeira, 1795

PAGE SPONSOR

Martin Heidegger (September 26, 1889 – May 26, 1976) was an influential German philosopher known for his existential and phenomenological explorations of the "question of Being." His best known book, Being and Time, is considered to be one of the most important philosophical works of the 20th century and he has been influential beyond philosophy, in literature, psychology, and artificial intelligence. Heidegger remains controversial due to his involvement with Nazism and statements in support of Adolf Hitler.

Heidegger claimed that Western philosophy since Plato, has misunderstood what it means for something "to be", tending to approach this question in terms of a being, rather than asking about Being itself. In other words, Heidegger believed all investigations of being have historically focused on particular entities and their properties, or have treated Being itself as an entity, or substance, with properties. A more authentic analysis of being would, for Heidegger, investigate "that on the basis of which beings are already understood", or that which underlies all particular entities and allows them to show up as entities in the first place. But since philosophers and scientists have overlooked the more basic, pre-theoretical ways of being from which their theories derive, and since they have incorrectly applied those theories universally, they have confused our understanding of being and human existence. To avoid these deep rooted misconceptions, Heidegger believed philosophical inquiry must be conducted in a new way, through a process of retracing the steps of the history of philosophy.

Heidegger argued that this misunderstanding, beginning with Plato, has left its traces in every stage of Western thought. All that we understand, from the way we speak to our notions of "common sense", is susceptible to error, to fundamental mistakes about the nature of being. These mistakes filter into the terms through which being is articulated in the history of philosophy — such as reality, logic, God, consciousness, and presence. In his later philosophy, Heidegger argues that this profoundly affects the way in which human beings relate to modern technology.

Heidegger's work has strongly influenced philosophy, theology and the humanities. Within philosophy it played a crucial role in the development of existentialism, hermeneutics, deconstructionism, postmodernism, and continental philosophy in general. Well known philosophers such as Karl Jaspers, Leo Strauss, Ahmad Fardid, Hans - Georg Gadamer, Jean - Paul Sartre, Emmanuel Lévinas, Hannah Arendt, Maurice Merleau - Ponty, Michel Foucault, Richard Rorty, William E. Connolly, and Jacques Derrida have all analyzed Heidegger's work.

Heidegger supported National Socialism and was a member of the Nazi Party from May 1933 until May 1945. His defenders, notably Hannah Arendt, see this support as arguably a personal " 'error' " (a word which Arendt placed in quotation marks when referring to Heidegger's Nazi - era politics). Defenders think this error was largely irrelevant to Heidegger's philosophy. Critics, such as his former students Emmanuel Levinas and Karl Löwith, claim that Heidegger's support for National Socialism revealed flaws inherent in his thought.

Heidegger was born in rural Meßkirch, Germany. Raised a Roman Catholic, he was the son of the sexton of the village church, Friedrich Heidegger, and his wife Johanna, née Kempf. In their faith, his parents adhered to the First Vatican Council of 1870, which was observed mainly by the poorer class of Meßkirch. The religious controversy between the wealthy Altkatholiken and the working class led to the temporary use of a converted barn for the Roman Catholics. At the festive reunion of the congregation in 1895, the Old Catholic sexton handed the key to six year old Martin.

Heidegger's

family could not afford to send him to university, so he entered a

Jesuit seminary, though he was turned away within weeks because of the

health requirement, and what he described as a psychosomatic heart condition. Heidegger later left Catholicism, describing it as incompatible with his philosophy. After studying theology at the University of Freiburg from

1909 to 1911, he switched to philosophy, in part again because of his

heart condition. Heidegger completed his doctoral thesis on psychologism in 1914 influenced by Neo - Thomism and Neo - Kantianism, and in 1916 finished his venia legendi with a thesis on Duns Scotus influenced by Heinrich Rickert and Edmund Husserl. In the two years following, he worked first as an unsalaried Privatdozent, then served as a soldier during the final year of World War I, working behind a desk and never leaving Germany.

After the war, he served as a salaried senior assistant to Edmund Husserl at the University of Freiburg from 1919 until 1923.

In 1923, Heidegger was elected to an extraordinary Professorship in Philosophy at the University of Marburg. His colleagues there included Rudolf Bultmann, Nicolai Hartmann, and Paul Natorp. Heidegger's students at Marburg included Hans - Georg Gadamer, Hannah Arendt, Karl Löwith, Gerhard Krüger, Leo Strauss, Jacob Klein, Gunther (Stern) Anders, and Hans Jonas. Through a confrontation with Aristotle he

began to develop in his lectures the main theme of his philosophy: the

question of the sense of being. He extended the concept of subject to

the dimension of history and concrete existence, which he found prefigured in such Christian thinkers as Saint Paul, Augustine of Hippo, Luther, and Kierkegaard. He also read the works of Dilthey, Husserl, and Max Scheler.

In 1927, Heidegger published his main work Sein und Zeit (Being and Time). When Husserl retired as Professor of Philosophy in 1928, Heidegger accepted Freiburg's election to be his successor, in spite of a counter - offer by Marburg. Heidegger remained at Freiburg im Breisgau for the rest of his life, declining a number of later offers, including one from Humboldt University of Berlin. His students at Freiburg included Charles Malik, Herbert Marcuse, and Ernst Nolte. Emmanuel Levinas attended his lecture courses during his stay in Freiburg in 1928.

Heidegger was elected rector of the University on April 21, 1933, and joined the National Socialist German Workers' (Nazi) Party on May 1. In his inaugural address as rector on May 27, and in political speeches and articles from the same year, he expressed his support for the Nazi cause and its leader, Adolf Hitler. He resigned the rectorate in April 1934, but remained a member of the Nazi party until 1945.

In late 1946, as France engaged in

épuration légale,

the French military authorities determined that Heidegger should be

forbidden from teaching or participating in any university activities

because of his association with the Nazi Party. The denazification procedures against Heidegger continued until March 1949, when he was finally pronounced a "Mitläufer"

(literally, mit = with, Läufer = runner, ie. "one who runs along

with", but the equivalent meaning in English is closer to "bandwagon

effect" or "herd instinct", standing for the notion that people often

do and believe things merely because many other people

do and believe the same things) of National Socialism, and no punitive

measures against him were proposed. This opened the way for his

readmission to teaching at Freiburg University in the winter semester

of 1950 – 51. He was granted emeritus status and then taught regularly from 1951 until 1958, and by invitation until 1967.

Heidegger married Elfride Petri on March 21, 1917, in a Catholic ceremony officiated by his friend Engelbert Krebs, and a week later in a Protestant ceremony in the presence of her parents. Their first son Jörg was born in 1919. According to published correspondence between the spouses, Hermann (born 1920) is the son of Elfride and Friedel Caesar.

Martin Heidegger had extramarital affairs with Hannah Arendt and Elisabeth Blochmann, both students of his. Arendt was Jewish, and Blochmann had one Jewish parent, making them subject to severe persecution by the Nazi authorities. He helped Blochmann emigrate from Germany prior to World War II, and resumed contact with both of them after the war.

Heidegger spent much time at his vacation home at Todtnauberg, on the edge of the Black Forest. He considered the seclusion provided by the forest to be the best environment in which to engage in philosophical thought.

Heidegger died on May 26, 1976, and was buried in the Meßkirch cemetery.

Adolf Hitler was sworn in as Chancellor of Germany on January 30, 1933. Heidegger was elected rector of the University of Freiburg on April 21, 1933, and assumed the position the following day. On May 1 he joined the Nazi Party. Heidegger delivered his inaugural address, the Rektoratsrede, on "Die Selbstbehauptung der Deutschen Universität" ("The Self - assertion of the German University") on May 27. Heidegger claimed that: "The German people must choose its future, and this future is bound to the Führer."

His tenure as rector was fraught with difficulties from the outset. Some National Socialist education officials viewed him as a rival, while others saw his efforts as comical. Some of Heidegger's fellow National Socialists also ridiculed his philosophical writings as gibberish. He finally offered his resignation on April 23, 1934, and it was accepted on April 27. Heidegger remained a member of both the academic faculty and of the Nazi Party until the end of the war. Philosophical historian Hans Sluga wrote:

Though as rector he prevented students from displaying an anti - Semitic poster at the entrance to the university and from holding a book burning, he kept in close contact with the Nazi student leaders and clearly signaled to them his sympathy with their activism.

In 1945 Heidegger wrote of his term as rector, giving the writing to his son Hermann; it was published in 1983:

Beginning in 1917, German - Jewish philosopher Edmund Husserl championed Heidegger's work, and helped him secure the retiring Husserl's chair in Philosophy at the University of Freiburg.The rectorate was an attempt to see something in the movement that had come to power, beyond all its failings and crudeness, that was much more far reaching and that could perhaps one day bring a concentration on the Germans' Western historical essence. It will in no way be denied that at the time I believed in such possibilities and for that reason renounced the actual vocation of thinking in favor of being effective in an official capacity. In no way will what was caused by my own inadequacy in office be played down. But these points of view do not capture what is essential and what moved me to accept the rectorate.

On April 6, 1933, the Reichskommissar of Baden Province, Robert Wagner, suspended all Jewish government employees, including present and retired faculty at the University of Freiburg. Heidegger's predecessor as Rector formally notified Husserl of his "enforced leave of absence" on April 14, 1933.

Heidegger became Rector of the University of Freiburg on April 22, 1933. The following week the national Reich law of April 28, 1933, replaced Reichskommissar Wagner's decree. The Reich law required the firing of Jewish professors from German universities, including those, such as Husserl, who had converted to Christianity. The termination of the retired professor Husserl's academic privileges thus did not involve any specific action on Heidegger's part.

Heidegger had by then broken off contact with Husserl, other than through intermediaries. Heidegger later claimed that his relationship with Husserl had already become strained after Husserl publicly "settled accounts" with Heidegger and Max Scheler in the early 1930s.

Heidegger did not attend his former mentor's cremation in 1938. In 1941, under pressure from publisher Max Niemeyer, Heidegger agreed to remove the dedication to Husserl from Being and Time (restored in post - war editions).

Heidegger's behavior towards Husserl has evoked controversy. Hannah Arendt initially suggested that Heidegger's behavior precipitated Husserl's death. She called Heidegger a "potential murderer." However, she later recanted her accusation.

After the failure of Heidegger's rectorship, he withdrew from most political activity, without canceling his membership in the NSDAP (Nazi Party). Nevertheless, references to National Socialism continued to appear in his work. The most controversial such reference occurred during a 1935 lecture which was published in 1953 as part of the book An Introduction to Metaphysics. In the published version, Heidegger refers to the "inner truth and greatness" of the National Socialist movement (die innere Wahrheit und Größe dieser Bewegung), but he then adds a qualifying statement in parentheses: "namely, the confrontation of planetary technology and modern humanity" (nämlich die Begegnung der planetarisch bestimmten Technik und des neuzeitlichen Menschen). However, it subsequently transpired that this qualification had not been made during the original lecture, although Heidegger claimed that it had been. This has led scholars to argue that Heidegger still supported the Nazi party in 1935 but that he did not want to admit this after the war, and so he attempted to silently correct his earlier statement.

In private notes written in 1939, Heidegger took a strongly critical view of Hitler's ideology, however in public lectures he seems to have continued to make ambiguous comments which, if they expressed criticism of the regime, did so only in the context of praising its ideals. For instance, in a 1942 lecture, published posthumously, Heidegger said of recent German classics scholarship: "In the majority of 'research results', the Greeks appear as pure National Socialists. This over enthusiasm on the part of academics seems not even to notice that with such "results" it does National Socialism and its historical uniqueness no service at all, not that it needs this anyhow.

An important witness to Heidegger's continued allegiance to National Socialism during the post rectorship period is his former student Karl Löwith, who met Heidegger in 1936 while Heidegger was visiting Rome. In an account set down in 1940 (though not intended for publication), Löwith recalled that Heidegger wore a swastika pin to their meeting, though Heidegger knew that Löwith was Jewish. Löwith also recalled that Heidegger "left no doubt about his faith in Hitler", and stated that his support for National Socialism was in agreement with the essence of his philosophy.

After the end of World War II, Heidegger was summoned to appear at a denazification hearing. Heidegger's former lover Hannah Arendt spoke on his behalf at this hearing, while Jaspers spoke against him. The result of the hearings was that Heidegger was forbidden to teach between 1945 and 1951. One consequence of this teaching ban was that Heidegger began to engage far more in the French philosophical scene.

In his postwar thinking, Heidegger distanced himself from Nazism, but his critical comments about Nazism seem "scandalous" to some since they tend to equate the Nazi war atrocities with other inhumane practices related to rationalisation and industrialisation, including the treatment of animals by factory farming. For instance in a lecture delivered at Bremen in 1949, Heidegger said: "Agriculture is now a motorized food industry, the same thing in its essence as the production of corpses in the gas chambers and the extermination camps, the same thing as blockades and the reduction of countries to famine, the same thing as the manufacture of hydrogen bombs."

In 1967 Heidegger met with the Jewish poet Paul Celan,

a concentration camp survivor. Celan visited Heidegger at his country

retreat and wrote an enigmatic poem about the meeting, which some

interpret as Celan's wish for Heidegger to apologize for his behavior during the Nazi era. On September 23, 1966, Heidegger was interviewed by Rudolf Augstein and Georg Wolff for Der Spiegel magazine,

in which he agreed to discuss his political past provided that the

interview be published posthumously (it was published on May 31, 1976).

In the interview, Heidegger defended his entanglement with National

Socialism in two ways: first, he argued that there was no alternative,

saying that he was trying to save the university (and science in

general) from being politicized and thus had to compromise with the

Nazi administration. Second, he admitted that he saw an "awakening" ("Aufbruch")

which might help to find a "new national and social approach", but said

that he changed his mind about this in 1934, largely prompted by the

violence of the Night of the Long Knives. In his interview Heidegger defended as double speak his

1935 lecture describing the "inner truth and greatness of this

movement." He affirmed that Nazi informants who observed his lectures

would understand that by "movement" he meant National Socialism.

However, Heidegger asserted that his dedicated students would know this

statement was no elegy for the NSDAP. Rather, he meant it as he

expressed it in the parenthetical clarification later added to An Introduction to Metaphysics (1953), namely, "the confrontation of planetary technology and modern humanity." The Löwith account from 1936 has been cited to contradict the account given in the Der Spiegel interview

in two ways: that there he did not make any decisive break with

National Socialism in 1934, and that Heidegger was willing to entertain

more profound relations between his philosophy and political

involvement. The Der Spiegel interviewers

did not bring up Heidegger's 1949 quotation comparing the

industrialization of agriculture to the extermination camps. In fact,

the interviewers were not in possession of much of the evidence now

known for Heidegger's Nazi sympathies.