<Back to Index>

- Aviation Pioneer Clément Ader, 1841

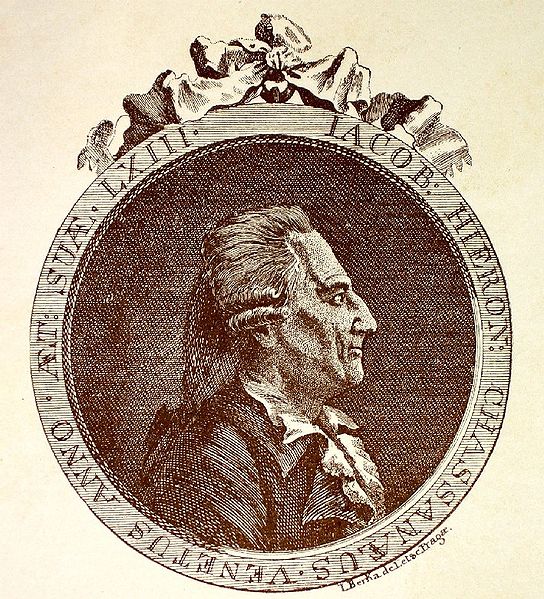

- Writer Giacomo Girolamo Casanova de Seingalt, 1725

- French Revolutionary Armand - Gaston Camus, 1740

PAGE SPONSOR

Giacomo Girolamo Casanova de Seingalt (April 2, 1725 – June 4, 1798) was an Italian adventurer and author from the Republic of Venice. His autobiography, Histoire de ma vie (Story of My Life), is regarded as one of the most authentic sources of the customs and norms of European social life during the 18th century.

He was so famous as a womanizer that his name remains synonymous with the art of seduction. He associated with European royalty, popes and cardinals, along with luminaries such as Voltaire, Goethe and Mozart. He spent his last years in Bohemia as a librarian in Count Waldstein's household, where he also wrote the story of his life. Giacomo Girolamo Casanova was born in Venice in 1725 to actress Zanetta Farussi, wife of actor and dancer Gaetano Giuseppe Casanova. Giacomo was the first of six children, being followed by Francesco Giuseppe (1727 – 1803), Giovanni Battista (1730 – 1795), Faustina Maddalena (1731 – 1736), Maria Maddalena Antonia Stella (1732 – 1800), and Gaetano Alvise (1734 – 1783). At the time of Casanova's birth, the Republic of Venice thrived

as the pleasure capital of Europe, ruled by political and religious

conservatives who tolerated social vices and encouraged tourism. It was

a required stop on the Grand Tour, traveled by young men coming of age, especially Englishmen. The famed Carnival, gambling houses, and beautiful courtesans were powerful drawing cards. This was the milieu that bred Casanova and made him its most famous and representative citizen. Casanova

was cared for by his grandmother Marzia Baldissera while his mother

toured about Europe in the theater. His father died when he was eight.

As a child, Casanova suffered nosebleeds, and his grandmother sought

help from a witch: “Leaving the gondola, we enter a hovel, where we

find an old woman sitting on a pallet, with a black cat in her arms and

five or six others around her.” Though the unguent applied was ineffective, Casanova was fascinated by the incantation. Perhaps

to remedy the nosebleeds (a physician blamed the density of Venice’s

air), Casanova, on his ninth birthday, was sent to a boarding house on

the mainland in Padua. For Casanova, the neglect by his parents was a bitter memory. “So they got rid of me,” he proclaimed. Conditions

at the boarding house were appalling so he appealed to be placed under

the care of Abbé Gozzi, his primary instructor, who tutored him

in academic subjects as well as the violin. Casanova moved in with the

priest and his family and lived there through most of his teenage years. It

was also in the Gozzi household that Casanova first came into contact

with the opposite sex, when Gozzi’s younger sister Bettina fondled him

at the age of eleven. Bettina was “pretty, lighthearted, and a great

reader of romances. … The girl pleased me at once, though I had no idea

why. It was she who little by little kindled in my heart the first

sparks of a feeling which later became my ruling passion.” Although she subsequently married, Casanova maintained a life - long attachment to Bettina and the Gozzi family. Early

on, Casanova demonstrated a quick wit, an intense appetite for

knowledge, and a perpetually inquisitive mind. He entered the University of Padua at twelve and graduated at seventeen, in 1742, with a degree in law (“for which I felt an unconquerable aversion”). It was his guardian’s hope that he would become an ecclesiastical lawyer. Casanova

had also studied moral philosophy, chemistry, and mathematics, and was

keenly interested in medicine. (“I should have been allowed to do as I

wished and become a physician, in which profession quackery is even

more effective than it is in legal practice.”) He frequently prescribed his own treatments for himself and friends. While

attending the university, Casanova began to gamble and quickly got into

debt, causing his recall to Venice by his grandmother, but the gambling

habit became firmly established. Back in Venice, Casanova started his clerical law career and was admitted as an abbé after being conferred minor orders by the Patriarch of Venice.

He shuttled back and forth to Padua to continue his university studies.

By now, he had become something of a dandy — tall and dark, his long hair

powdered, scented, and elaborately curled. He quickly ingratiated

himself with a patron (something he was to do all his life),

76 year old Venetian senator Alvise Gasparo Malipiero, the owner of Palazzo Malipiero,

close to Casanova’s home in Venice. Malipiero

moved in the best circles and taught young Casanova a great deal about

good food and wine, and how to behave in society. When Casanova was

caught dallying with Malipiero’s intended object of seduction, actress

Teresa Imer, however, the senator drove both of them from his house. Casanova’s

growing curiosity about women led to his first complete sexual

experience, with two sisters Nanetta and Maria Savorgnan, then fourteen

and sixteen, who were distant relatives of the Grimanis. Casanova proclaimed that his life avocation was firmly established by this encounter.

Scandals

tainted Casanova’s short church career. After his grandmother’s death,

Casanova entered a seminary for a short while, but soon his

indebtedness landed him in prison for the first time. An attempt by his

mother to secure him a position with bishop Bernardo de Bernardis was

rejected by Casanova after a very brief trial of conditions in the

bishop's Calabrian see. Instead, he found employment as a scribe with the powerful Cardinal Acquaviva in Rome. On meeting the pope,

Casanova boldly asked for a dispensation to read the “forbidden books”

and from eating fish (which he claimed inflamed his eyes). He also

composed love letters for another cardinal. But when Casanova became

the scapegoat for a scandal involving a local pair of star - crossed

lovers, Cardinal Acquaviva dismissed Casanova, thanking him for his

sacrifice, but effectively ending his church career. In search of a new profession, Casanova bought a commission to become a military officer for the Republic of Venice. His first step was to look the part: Reflecting

that there was now little likelihood of my achieving fortune in my

ecclesiastical career, I decided to dress as a soldier … I inquire for

a good tailor … he brings me everything I need to impersonate a

follower of Mars. … My uniform was white, with a blue vest, a shoulder

knot of silver and gold… I bought a long sword, and with my handsome

cane in hand, a trim hat with a black cockade, with my hair cut in side

whiskers and a long false pigtail, I set forth to impress the whole

city. He joined a Venetian regiment at Corfu, his stay being broken by a brief trip to Constantinople, ostensibly to deliver a letter from his former master the Cardinal. He found his advancement too slow and his duty boring, and he managed to lose most of his pay playing faro. Casanova soon abandoned his military career and returned to Venice. At

the age of 21, he set out to become a professional gambler but losing

all his remaining money from the sale of his commission, he turned to

his old benefactor Alvise Grimani for a job. Casanova thus began his

third career, as a violinist in the San Samuele theater, “a menial

journeyman of a sublime art in which, if he who excels is admired, the

mediocrity is rightly despised. ... My profession was not a noble one,

but I did not care. Calling everything prejudice, I soon acquired all

the habits of my degraded fellow musicians.” He

and some of his fellows, “often spent our nights roaming through

different quarters of the city, thinking up the most scandalous

practical jokes and putting them into execution ... we amused ourselves

by untying the gondolas moored before private homes, which then drifted

with the current”. They also sent midwives and physicians on false

calls. Good

fortune came to the rescue when Casanova, unhappy with his lot as a

musician, saved the life of a Venetian nobleman of the Bragadin family,

who had a stroke while riding with Casanova in a gondola after a

wedding ball. They immediately stopped to have the senator bled. Then,

at the senator’s palace, a physician bled the senator again and applied

an ointment of mercury to

the senator’s chest (mercury was an all purpose but toxic remedy of the

time). The mercury raised his temperature and induced a massive fever,

and Bragadin appeared to be choking on his own swollen windpipe.

A priest was called as death seemed to be approaching. Casanova,

however, took charge and taking responsibility for a change in

treatment, under protest from the attending physician, ordered the

removal of the ointment and the washing of the senator's chest with

cool water. The senator recovered from his illness with rest and a

sensible diet. Because

of his youth and his facile recitation of medical knowledge, the

senator and his two bachelor friends thought Casanova wise beyond his

years, and concluded that he must be in possession of occult knowledge.

As they were cabalists themselves, the senator invited Casanova into his household and he became a life long patron. Casanova stated in his memoirs: I

took the most creditable, the noblest, and the only natural course. I

decided to put myself in a position where I need no longer go without

the necessities of life: and what those necessities were for me no one

could judge better than me.... No one in Venice could understand how an

intimacy could exist between myself and three men of their character,

they all heaven and I all earth; they most severe in their morals, and

I addicted to every kind of dissolute living. For

the next three years under the senator’s patronage, working nominally

as a legal assistant, Casanova led the life of a nobleman, dressed

magnificently, and as was natural to him, spending most of his time

gambling and engaging in amorous pursuits. His

patron was exceedingly tolerant, but he warned Casanova that some day

he would pay the price; “I made a joke of his dire Prophecies and went

my way.” However, not much later, Casanova was forced to leave Venice,

due to further scandals. Casanova had dug up a freshly buried corpse in

order to play a practical joke on an enemy and exact revenge — but the

victim went into a paralysis, never to recover. And in another scandal,

a young girl who had duped him accused him of rape and went to the

officials. Casanova was later acquitted of this crime for lack of evidence, but by this time he had already fled out of Venice. Escaping to Parma,

Casanova entered into a three month affair with a Frenchwoman he named

“Henriette”, perhaps the deepest love he ever experienced — a woman who

combined beauty, intelligence, and culture. In his words, “They who

believe that a woman is incapable of making a man equally happy all the

twenty - four hours of the day have never known an Henriette. The joy

which flooded my soul was far greater when I conversed with her during

the day than when I held her in my arms at night. Having read a great

deal and having natural taste, Henriette judged rightly of everything.” She also judged Casanova astutely. As noted Casanovist J. Rives Childs wrote: Perhaps

no woman so captivated Casanova as Henriette; few women obtained so

deep an understanding of him. She penetrated his outward shell early in

their relationship, resisting the temptation to unite her destiny with

his. She came to discern his volatile nature, his lack of social

background, and the precariousness of his finances. Before leaving, she

slipped into his pocket five hundred louis, mark of her evaluation of

him.

Crestfallen and despondent, Casanova returned to Venice, and after a good gambling streak, he recovered and set off on a

Grand Tour, reaching Paris in 1750. Along the way, from one town to another, he got into sexual escapades resembling operatic plots. In Lyon, he entered the society of Freemasonry,

which appealed to his interest in secret rites and which, for the most

part, attracted men of intellect and influence who proved useful in his

life, providing valuable contacts and uncensored knowledge. Casanova

was also attracted to Rosicrucianism. Casanova

stayed in Paris for two years, learned the language, spent much time at

the theatre, and introduced himself to notables. Soon, however, his

numerous liaisons were noted by the Paris police, as they were in

nearly every city he visited. He moved on to Dresden in 1752 and encountered his mother. He wrote a well received play La Moluccheide, now lost. He then visited Prague, and Vienna, where the tighter moral atmosphere was not to his liking. He finally returned to Venice in 1753. In

Venice, Casanova resumed his wicked escapades, picking up many enemies,

and gaining the greater attention of the Venetian inquisitors. His

police record became a lengthening list of reported blasphemies,

seductions, fights, and public controversy. A

state spy, Giovanni Manucci, was employed to draw out Casanova’s

knowledge of cabalism and Freemasonry, and to examine his library for

forbidden books. Senator Bragadin, in total seriousness this time

(being formerly an inquisitor himself), advised his “son” to leave

immediately or face the stiffest consequences. The

following day, at age thirty, Casanova was arrested: “The Tribunal,

having taken cognizance of the grave faults committed by G. Casanova

primarily in public outrages against the holy religion, their

Excellencies have caused him to be arrested and imprisoned under the

Leads.” “The Leads” was a prison of seven cells on the top floor of the east wing of the Doge's palace,

reserved for prisoners of higher status and political crimes and named

for the lead plates covering the palace roof. Without a trial, Casanova

was sentenced to five years in the “unescapable” prison. He was placed in solitary confinement with clothing, a pallet bed, table and armchair in "the worst of all the cells", where

he suffered greatly from the darkness, summer heat and "millions of

fleas." He was soon housed with a series of cell mates, and after five

months and a personal appeal from Count Bragadin was given warm winter

bedding and a monthly stipend for books and better food. During

exercise walks he was granted in the prison garret, he found a piece of

black marble and an iron bar which he smuggled back to his cell; he hid

the bar inside his armchair. When he was temporarily without cell

mates, he spent two weeks sharpening the bar into a spike on the stone.

Then he began to gouge through the wooden floor underneath his bed,

knowing that his cell was directly above the Inquisitor’s chamber. Just

three days before his intended escape, during a festival when no

officials would be in the chamber below, Casanova was moved to a

larger, lighter cell with a view, despite his protests that he was

perfectly happy where he was. In his new cell, “I sat in my armchair

like a man in a stupor; motionless as a statue, I saw that I had wasted

all the efforts I had made, and I could not repent of them. I felt that

I had nothing to hope for, and the only relief left to me was not to

think of the future.” Overcoming

his inertia, Casanova set upon another escape plan. He solicited the

help of the prisoner in the adjacent cell, Father Balbi, a renegade

priest. The spike, carried to the new cell inside the armchair, was

passed to the priest in a folio Bible carried under a heaping plate of

pasta by the hoodwinked jailer. The priest made a hole in his ceiling,

climbed across and made a hole in the ceiling of Casanova’s cell. To

neutralize his new cell mate, who was a spy, Casanova played on his

superstitions and terrorized him into silence. When

Balbi broke through to Casanova’s cell, Casanova lifted himself through

the ceiling, leaving behind a note that quoted the 117th Psalm

(Vulgate): “I shall not die, but live, and declare the works of the

Lord”. The

spy remained behind, too frightened of the consequences if he would be

caught escaping with the others. Casanova and Balbi pried their way

through the lead plates and onto the sloping roof of the Doge’s Palace,

with a heavy fog swirling. The drop to the nearby canal being too

great, Casanova pried open the grate over a dormer window, and broke

the window to gain entry. They found a long ladder on the roof, and

with the additional use of ropes, lowered themselves into the room

whose floor was twenty - five feet below. They rested until morning,

changed clothes, then broke a small lock on an exit door and passed

into a palace corridor, through galleries and chambers, down stairs,

and out a final door. It was six in the morning and they escaped by

gondola. Eventually, Casanova reached Paris, where he arrived on the

same day (January 5, 1757) that Robert - François Damiens made an attempt on the life of Louis XV, and later witnessed and described his execution. Skeptics

contend that Casanova’s tale of escape is implausible, and that he

simply bribed his way to freedom with the help of his patron. However,

some physical evidence does exist in the state records, including

repairs to the cell ceilings. Thirty years later in 1787, Casanova wrote Story of My Flight, which was very popular and was reprinted in many languages, and he repeated the tale a little later in his memoirs. Casanova's judgment of the exploit is characteristic: Thus

did God provide me with what I needed for an escape which was to be a

wonder if not a miracle. I admit that I am proud of it; but my pride

does not come from my having succeeded, for luck had a good deal to do

with that; it comes from my having concluded that the thing could be

done and having had the courage to undertake it."

He

knew his stay in Paris might be a long one and he proceeded

accordingly: “I saw that to accomplish anything I must bring all my

physical and moral faculties in play, make the acquaintance of the

great and the powerful, exercise strict self control, and play the

chameleon.” Casanova

had matured, and this time in Paris, though still depending at times on

quick thinking and decisive action, he was more calculating and

deliberate. His first task was to find a new patron. He reconnected

with old friend de Bernis, now the Foreign Minister of France. Casanova

was advised by his patron to find a means of raising funds for the

state as a way to gain instant favor. Casanova promptly became one of

the trustees of the first state lottery, and one of its best ticket salesmen. The enterprise earned him a large fortune quickly. With

money in hand, he traveled in high circles and undertook new

seductions. He duped many socialites with his occultism, particularly

the Marquise Jeanne d'Urfé, using his excellent memory which made him appear to have a sorcerer’s power of numerology. In Casanova’s view, “deceiving a fool is an exploit worthy of an intelligent man”. Casanova claimed to be a Rosicrucian and an alchemist, aptitudes which made him popular with some of the most prominent figures of the era, among them Madame de Pompadour, Count de Saint - Germain, d'Alembert and Jean - Jacques Rousseau.

So popular was alchemy among the nobles, particularly the search for

the “philosopher’s stone”, that Casanova was highly sought after for

his supposed knowledge, and he profited handsomely. He

met his match, however, in the Count de Saint - Germain: “This very

singular man, born to be the most barefaced of all imposters, declared

with impunity, with a casual air, that he was three hundred years old,

that he possessed the universal medicine, that he made anything he

liked from nature, that he created diamonds.” De

Bernis decided to send Casanova to Dunkirk on his first spying mission.

Casanova was paid well for his quick work and this experience prompted

one of his few remarks against the ancien régime and

the class he was dependent on. He remarked in hindsight, “All the

French ministers are the same. They lavished money which came out of

the other people’s pockets to enrich their creatures, and they were

absolute: The down trodden people counted for nothing, and, through

this, the indebtedness of the State and the confusion of finances were

the inevitable results. A Revolution was necessary.” As the Seven Years War began, Casanova was again called to help increase the state treasury. He was entrusted with a mission of selling state bonds in Amsterdam, Holland being the financial center of Europe at the time. He

succeeded in selling the bonds at only an 8% discount, and the

following year was rich enough to found a silk manufactory with his

earnings. The French government even offered him a title and a pension

if he would become a French citizen and work on behalf of the Finance

Ministry, but he declined, perhaps because it would frustrate his Wanderlust. Casanova

had reached his peak of fortune but could not sustain it. He ran the

business poorly, borrowed heavily trying to save it, and spent much of

his wealth on constant liaisons with his female workers who were his “harem”. For his debts, Casanova was imprisoned again, this time at For - l'Évêque,

but was liberated four days afterwards, upon the insistence of the

Marquise d'Urfé. Unfortunately, though he was released, his

patron de Bernis was dismissed by Louis XV at

that time and Casanova’s enemies closed in on him. He sold the rest of

his belongings and secured another mission to Holland to distance

himself from his troubles.

This time, however, his mission failed and he fled to

Cologne, then Stuttgart in the spring of 1760, where he lost the rest of his fortune. He was yet again arrested for his debts, but managed to escape to Switzerland. Weary of his wanton life, Casanova visited the monastery of Einsiedeln and

considered the simple, scholarly life of a monk. He returned to his

hotel to think on the decision only to encounter a new object of

desire, and reverting to his old instincts, all thoughts of a monk’s

life were quickly forgotten. Moving on, he visited Albrecht von Haller and Voltaire, and arrived in Marseille, then Genoa, Florence, Rome, Naples, Modena, and Turin, moving from one sexual romp to another. In 1760, Casanova started styling himself the Chevalier de

Seingalt, a name he would increasingly use for the rest of his life. On

occasion, he would also call himself Count de Farussi (using his

mother's maiden name) and when Pope Clement XIII presented Casanova with the Papal Order of the Éperon d'Òr, he had an impressive cross and ribbon to display on his chest. Back

in Paris, he set about one of his most outrageous schemes — convincing

his old dupe the Marquise d'Urfé that he could turn her into a

young man through occult means. The plan did not yield Casanova the big

payoff he had hoped for, and the Marquise d'Urfé finally lost

faith in him. Casanova

traveled to England in 1763, hoping to sell his idea of a state lottery

to English officials. He wrote of the English, “the people have a

special character, common to the whole nation, which makes them think

they are superior to everyone else. It is a belief shared by all

nations, each thinking itself the best. And they are all right.” Through

his connections, he worked his way up to an audience with King George

III, using most of the valuables he had stolen from the Marquise

d'Urfé. While working the political angles, he also spent much

time in the bedroom, as was his habit. As a means to find females for

his pleasure, not being able to speak English, he put an advertisement

in the newspaper to let an apartment to the “right” person. He

interviewed many young women, choosing one “Mistress Pauline” who

suited him well. Soon, he established himself in her apartment and

seduced her. These and other liaisons, however, left him weak with venereal disease and he left England broke and ill. He

went on to Belgium, recovered, and then for the next three years,

traveled all over Europe, covering about 4,500 miles by coach over

rough roads, and going as far as Moscow (the

average daily coach trip being about 30 miles in a day). Again, his

principal goal was to sell his lottery scheme to other governments and

repeat the great success he had with the French government. But a

meeting with Frederick the Great bore

no fruit and in the surrounding German lands, the same result. Not

lacking either connections or confidence, Casanova went to Russia and

met with Catherine the Great but she flatly turned down the lottery idea. In 1766, he was expelled from Warsaw following a pistol duel with Colonel Count Franciszek Ksawery Branicki over

an Italian actress, a lady friend of theirs. Both duelists were

wounded, Casanova on the left hand. The hand recovered on its own,

after Casanova refused the recommendation of doctors that it be

amputated. Other

stops failed to gain any takers for the lottery. He returned to Paris

for several months in 1767 and hit the gambling salons, only to be

expelled from France by order of Louis XV himself, primarily for

Casanova’s scam involving the Marquise d'Urfé. Now

known across Europe for his reckless behavior, Casanova would have

difficulty overcoming his notoriety and gaining any fortune. So he

headed for Spain, where he was not as well known. He tried his usual

approach, leaning on well placed contacts (often Freemasons), wining

and dining with nobles of influence, and finally arranging an audience

with the local monarch, in this case Charles III. When no doors opened

for him, however, he could only roam across Spain, with little to show

for it. In Barcelona, he escaped assassination and landed in jail for

six weeks. His Spanish adventure a failure, he returned to France

briefly, then to Italy.

In

Rome, Casanova had to prepare a way for his return to Venice. While

waiting for supporters to gain him legal entry into Venice, Casanova

began his modern Tuscan - Italian translation of the

Iliad, his History of the Troubles in Poland,

and a comic play. To ingratiate himself with the Venetian authorities,

Casanova did some commercial spying for them. After months without a

recall, however, he wrote a letter of appeal directly to the

Inquisitors. At last, he received his long sought permission and burst

into tears upon reading “We, Inquisitors of State, for reasons known to

us, give Giacomo Casanova a free safe conduct ... empowering him to

come, go, stop, and return, hold communication wheresoever he pleases

without let or hindrance. So is our will.” Casanova was permitted to

return to Venice in September 1774 after eighteen years of exile. At

first, his return to Venice was a cordial one and he was a celebrity.

Even the Inquisitors wanted to hear how he had escaped from their

prison. Of his three bachelor patrons, however, only Dandolo was still

alive and Casanova was invited back to live with him. He received a

small stipend from Dandolo and hoped to live from his writings, but

that was not enough. He reluctantly became a spy again for Venice, paid

by piece work, reporting on religion, morals, and commerce, most of it

based on gossip and rumor he picked up from social contacts. He was disappointed. No financial opportunities of interest came about and few doors opened for him in society as in the past. At

age 49, the years of reckless living and the thousands of miles of

travel had taken its toll. Casanova’s smallpox scars, sunken cheeks,

and hook nose became all the more noticeable. His easygoing manner was

now more guarded. Prince Charles de Ligne, a friend (and uncle of his future employer), described him around 1784: He

would be a good looking man if he were not ugly; he is tall and built

like Hercules, but of an African tint; eyes full of life and fire, but

touchy, wary, rancorous — and this gives him a ferocious air. It is

easier to put him in a rage than to make him gay. He laughs little, but

makes other laugh. ... He has a manner of saying things which reminds me of Harlequin or Figaro, and which makes them sound witty. Venice

had changed for him. Casanova now had little money for gambling, few

willing females worth pursuing, and few acquaintances to enliven his

dull days. He heard of the death of his mother and more paining, he

went to the bedside of Bettina Gozzi, who had first introduced him to

sex, and she died in his arms. His Iliad was published in three volumes, but to limited subscribers and yielding little money. He got into a published dispute with Voltaire over

religion. When he asked, “Suppose that you succeed in destroying

superstition. With what will you replace it?” Voltaire shot back, “I

like that. When I deliver humanity from a ferocious beast which devours

it, can I be asked what I shall put in its place.” From Casanova’s

point of view, if Voltaire had “been a proper philosopher, he would

have kept silent on that subject ... the people need to live in

ignorance for the general peace of the nation”. In

1779, Casanova found Francesca, an uneducated seamstress, who became

his live in lover and housekeeper, and who loved him devotedly. Later

that year, the Inquisitors put him on the payroll and sent him to

investigate commerce between the Papal states and Venice. Other

publishing and theater ventures failed, primarily from lack of capital.

In a downward spiral, Casanova was expelled again from Venice in 1783,

after writing a vicious satire poking fun at Venetian nobility. In it

he made his only public statement that Grimani was his true father. Forced to resume his travels again, Casanova arrived in Paris, and in November 1783 met Benjamin Franklin while attending a presentation on aeronautics and the future of balloon transport. For

a while, Casanova served as secretary and pamphleteer to Sebastian

Foscarini, Venetian ambassador in Vienna. He also became acquainted with Lorenzo Da Ponte, Mozart’s librettist, who noted about Casanova, “This singular man never liked to be in the wrong.” Notes by Casanova indicate that he may have made suggestions to Da Ponte concerning the libretto for Mozart’s Don Giovanni.

In

1785, after Foscarini died, Casanova began searching for another

position. A few months later, he became the librarian to Count Joseph

Karl von Waldstein, a

chamberlain of the emperor, in the Castle of Dux, Bohemia (Duchcov Castle, Czech Republic). The Count — himself a Freemason, cabalist, and frequent traveler — had

taken to Casanova when they had met a year earlier at Foscarini’s

residence. Although the job offered security and good pay, Casanova

describes his last years as boring and frustrating, even though it was

the most productive time for writing. His

health had deteriorated dramatically and he found life among peasants

to be less than stimulating. He was only able to make occasional visits

to Vienna and Dresden for

relief. Although Casanova got on well with the Count, his employer was

a much younger man with his own eccentricities. The Count often ignored

him at meals and failed to introduce him to important visiting guests.

Moreover, Casanova, the testy outsider, was thoroughly disliked by most

of the other inhabitants of the Castle of Dux. Casanova’s only friends

seemed to be his fox terriers. In despair, Casanova considered suicide,

but instead decided that he must live on to record his memoirs, which

he did until his death. In 1797, word arrived that the Republic of Venice had ceased to exist and Napoleon Bonaparte had

seized Casanova’s home city. It was too late to return home. Casanova

died on June 4, 1798, at age 73. His last words are said to have been

“I have lived as a philosopher and I die as a Christian”.

The isolation and boredom of Casanova’s last years enabled him to focus without distractions on his

Histoire de ma vie,

without which his fame would have been considerably diminished, if not

blotted out entirely. He began to think about writing his memoirs

around 1780 and began in earnest by 1789, as “the only remedy to keep

from going mad or dying of grief”. The first draft was completed by

July 1792, and he spent the next six years revising it. He puts a happy

face on his days of loneliness, writing in his work, “I can find no

pleasanter pastime than to converse with myself about my own affairs

and to provide a most worthy subject for laughter to my well bred

audience.” His recollections only go up to the summer of 1774. His

memoirs were still being compiled at the time of his death. A letter by

him in 1792 states that he was reconsidering his decision to publish

them believing his story was despicable and he would make enemies by

writing the truth about his affairs. But he decided to proceed and to

use initials instead of actual names, and to tone down its strongest

passages. He wrote in French instead of Italian because “the French language is more widely known than mine”. The memoirs open with: I

begin by declaring to my reader that, by everything good or bad that I

have done throughout my life, I am sure that I have earned merit or

incurred guilt, and that hence I must consider myself a free agent. ...

Despite an excellent moral foundation, the inevitable fruit of the

divine principles which were rooted in my heart, I was all my life the

victim of my senses; I have delighted in going astray and I have

constantly lived in error, with no other consolation than that of

knowing I have erred. ... My follies are the follies of youth. You will

see that I laugh at them, and if you are kind you will laugh at them

with me. Casanova wrote about the purpose of his book: I

expect the friendship, the esteem, and the gratitude of my readers.

Their gratitude, if reading my memoirs will have given instruction and

pleasure. Their esteem if, doing me justice, they will have found that

I have more virtues than faults; and their friendship as soon as they

come to find me deserving of it by the frankness and good faith with

which I submit myself to their judgment without in any way disguising

what I am. He

also advises his readers that they “will not find all my adventures. I

have left out those which would have offended the people who played a

part in them, for they would cut a sorry figure in them. Even so, there

are those who will sometimes think me too indiscreet; I am sorry for

it.” And

in the final chapter, the text abruptly breaks off with hints at

adventures unrecorded: “Three years later I saw her in Padua, where I

resumed my acquaintance with her daughter on far more tender terms.” Uncut,

the memoirs ran to twelve volumes, and the abridged American

translation runs to nearly 1200 pages. Though his chronology is at

times confusing and inaccurate, and many of his tales exaggerated, much

of his narrative and many details are corroborated by contemporary

writings. He has a good ear for dialogue and writes at length about all

classes of society. Casanova, for the most part, is candid about his faults, intentions, and

motivations, and shares his successes and failures with good humor. The

confession is largely devoid of repentance or remorse. He celebrates

the senses with his readers, especially regarding music, food, and

women. “I have always liked highly seasoned food. ... As for women, I

have always found that the one I was in love with smelled good, and the

more copious her sweat the sweeter I found it.” He mentions over 120 adventures with women and girls, with several veiled references to male lovers as well. He

describes his duels and conflicts with scoundrels and officials, his

entrapments and his escapes, his schemes and plots, his anguish and his

sighs of pleasure. He demonstrates convincingly, “I can say vixi (‘I have lived’).” The

manuscript of Casanova’s memoirs was held by his relatives until it was

sold to F. A. Brockhaus publishers, and first published in heavily

abridged versions in German around 1822, then in French. During World

War II, the manuscript survived the allied bombing of Leipzig. The

memoirs were heavily pirated through the ages and have been translated

into some twenty languages. But not until 1960 was the entire text

published in its original language of French. In 2010 the manuscript was acquired by the National Library of France, which has started digitizing it.

For Casanova, as well as his contemporary

sybarites of

the upper class, love and sex tended to be casual and not endowed with

the seriousness characteristic of the Romanticism of the 19th century. Flirtations,

bedroom games, and short term liaisons were common among nobles who

married for social connections rather than love. For Casanova, it was

an open field of sexual opportunities. Although

multi - faceted and complex, Casanova's personality was dominated by his

sensual urges: “Cultivating whatever gave pleasure to my senses was

always the chief business of my life; I never found any occupation more

important. Feeling that I was born for the sex opposite of mine, I have

always loved it and done all that I could to make myself loved by it.” He noted that he sometimes used "assurance caps" to prevent impregnating his mistresses. Casanova’s

ideal liaison had elements beyond sex, including complicated plots,

heroes and villains, and gallant outcomes. In a pattern he often

repeated, he would discover an attractive woman in trouble with a

brutish or jealous lover (Act I); he would ameliorate her difficulty

(Act II); she would show her gratitude; he would seduce her; a short

exciting affair would ensue (Act III); feeling a loss of ardor or

boredom setting in, he would plead his unworthiness and arrange for her

marriage or pairing with a worthy man, then exit the scene (Act IV). As William Bolitho points out in Twelve Against the Gods,

the secret of Casanova's success with women “had nothing more esoteric

in it than [offering] what every woman who respects herself must

demand: all that he had, all that he was, with (to set off the lack of

legality) the dazzling attraction of the lump sum over what is more

regularly doled out in a lifetime of installments.” Casanova

advises, “There is no honest woman with an uncorrupted heart whom a man

is not sure of conquering by dint of gratitude. It is one of the surest

and shortest means.” Alcohol and violence, for him, were not proper tools of seduction. Instead,

attentiveness and small favors should be employed to soften a woman’s

heart, but “a man who makes known his love by words is a fool”. Verbal

communication is essential — “without speech, the pleasure of love is

diminished by at least two-thirds” — but words of love must be implied,

not boldly proclaimed. Mutual

consent is important, according to Casanova, but he avoided easy

conquests or overly difficult situations as not suitable for his

purposes. He

strove to be the ideal escort in the first act — witty, charming,

confidential, helpful — before moving into the bedroom in the third act.

Casanova claims not to be predatory (“my guiding principle has been

never to direct my attack against novices or those whose prejudices

were likely to prove an obstacle”); however, his conquests did tend to

be insecure or emotionally exposed women. Casanova

valued intelligence in a woman: “After all, a beautiful woman without a

mind of her own leaves her lover with no resource after he had

physically enjoyed her charms.” His attitude towards educated women,

however, was typical for his time: “In a woman learning is out of

place; it compromises the essential qualities of her sex ... no

scientific discoveries have been made by women ... (which) requires a

vigor which the female sex cannot have. But in simple reasoning and in

delicacy of feeling we must yield to women.”

Gambling was

a common recreation in the social and political circles in which

Casanova moved. In his memoirs, Casanova discusses many forms of 18th

century gambling — including lotteries, faro, basset, piquet, biribi, primero, quinze, and whist — and the passion for it among the nobility and the high clergy. Cheaters

(known as “correctors of fortune”) were somewhat more tolerated than

today in public casinos and in private games for invited players, and

seldom caused affront. Most gamblers were on guard against cheaters and

their tricks. Scams of all sorts were common, and Casanova was amused

by them. Casanova

gambled throughout his adult life, winning and losing large sums. He

was tutored by professionals, and he was “instructed in those wise

maxims without which games of chance ruin those who participate in

them”. He was not above occasionally cheating and at times even teamed

with professional gamblers for his own profit. Casanova claims that he

was “relaxed and smiling when I lost, and I won without covetousness”.

However, when outrageously duped himself, he could act violently, sometimes calling for a duel. Casanova

admits that he was not disciplined enough to be a professional gambler:

“I had neither prudence enough to leave off when fortune was adverse,

nor sufficient control over myself when I had won.” Nor

did he like being considered as a professional gambler: “Nothing could

ever be adduced by professional gamblers that I was of their infernal clique.” Although

Casanova at times used gambling tactically and shrewdly — for making

quick money, for flirting, making connections, acting gallantly, or

proving himself a gentleman among his social superiors — his practice

also could be compulsive and reckless, especially during the euphoria

of a new sexual affair. "Why did I gamble when I felt the losses so

keenly? What made me gamble was avarice. I loved to spend, and my heart

bled when I could not do it with money won at cards."

Although

best known for his prowess in seduction for more than two hundred years

since his death, Casanova was also recognized by his contemporaries as

an extraordinary person, a man of far ranging intellect and curiosity.

Casanova was one of the foremost chroniclers of his age. He was a true

adventurer, traveling across Europe from end to end in search of

fortune, seeking out the most prominent people of his time to help his

cause. He was a servant of the establishment and equally decadent as

his times, but also a participant in secret societies and a seeker of

answers beyond the conventional. He was religious, a devout Catholic,

and believed in prayer: “Despair kills; prayer dissipates it; and after

praying man trusts and acts.” Along with prayer he also believed in

free will and reason, but clearly did not subscribe to the notion that

pleasure seeking would keep him from heaven. He

was, by vocation and avocation, a lawyer, clergyman, military officer,

violinist, con man, pimp, gourmand, dancer, businessman, diplomat, spy,

politician, mathematician, social philosopher, cabalist, playwright,

and writer. He wrote over twenty works, including plays and essays, and

many letters. His novel Icosameron is an early work of science fiction. Born

of actors, he had a passion for the theater and for an improvised,

theatrical life. But with all his talents, he frequently succumbed to

the quest for pleasure and sex, often avoiding sustained work and

established plans, and got himself into trouble when prudent action

would have served him better. His true occupation was living largely on

his quick wits, steely nerves, luck, social charm, and the money given

to him in gratitude and by trickery. Prince Charles de Ligne,

who understood Casanova well, and who knew most of the prominent

individuals of the age, thought Casanova the most interesting man he

had ever met: “there is nothing in the world of which he is not

capable.” Rounding out the portrait, the Prince also stated: The

only things about which he knows nothing are those which he believes

himself to be expert: the rules of the dance, the French language, good

taste, the way of the world, savoir vivre.

It is only his comedies which are not funny, only his philosophical

works which lack philosophy — all the rest are filled with it; there is

always something weighty, new, piquant, profound. He is a well of

knowledge, but he quotes Homer and Horace ad nauseam. His wit and his sallies are like Attic salt. He is sensitive and

generous, but displease him in the slightest and he is unpleasant,

vindictive, and detestable. He believes in nothing except what is most

incredible, being superstitious about everything. He loves and lusts

after everything. ... He is proud because he is nothing. ... Never tell

him you have heard the story he is going to tell you. ... Never omit to

greet him in passing, for the merest trifle will make him your enemy. “Casanova”, like “Don Juan”, is a long established term in the English language. According to Merriam Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, 11th ed., the noun Casanova means “Lover; esp:

a man who is a promiscuous and unscrupulous lover”. The first usage of

the term in written English was around 1852. References in culture to

Casanova are numerous — in books, films, theater, and music.