<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Eberhard Frederich Ferdinand Hopf, 1902

- Painter Maurice de Vlaminck, 1876

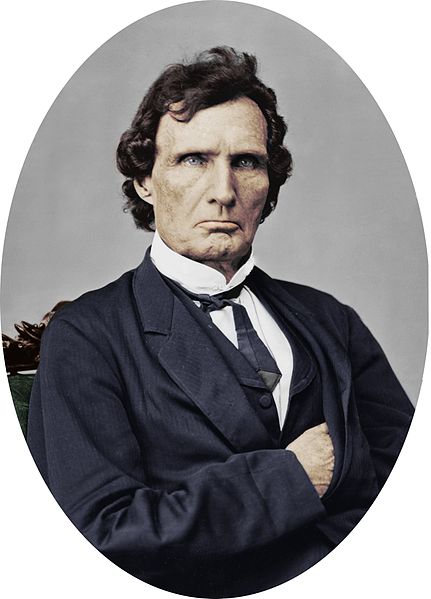

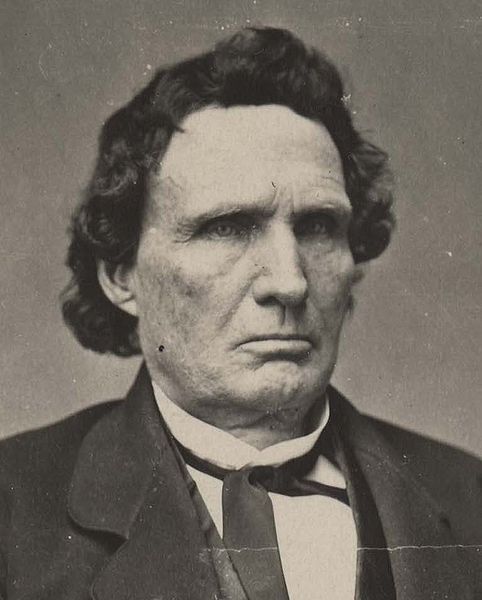

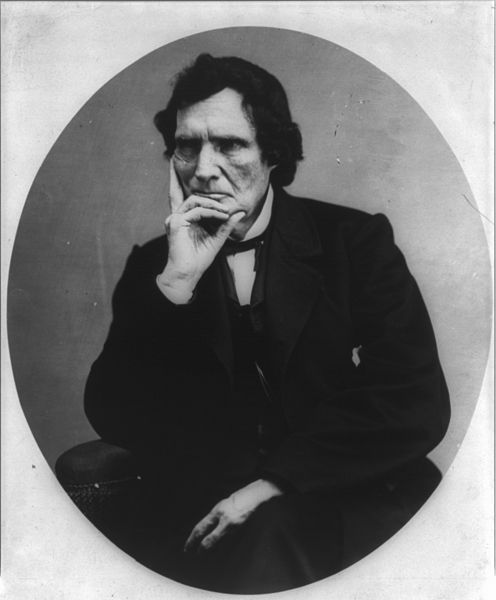

- Member U.S. House of Representatives Thaddeus Stevens, 1792

PAGE SPONSOR

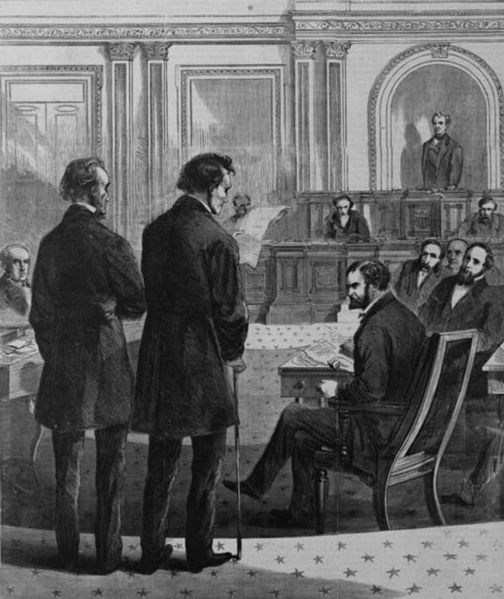

Thaddeus Stevens (April 4, 1792 – August 11, 1868), of Pennsylvania, was a Republican leader and one of the most powerful members of the United States House of Representatives. As chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, Stevens, a witty, sarcastic speaker and flamboyant party leader, dominated the House from 1861 until his death and wrote much of the financial legislation that paid for the American Civil War. Stevens and Senator Charles Sumner were the prime leaders of the Radical Republicans during the American Civil War and Reconstruction. A biographer characterizes him as, "The Great Commoner, savior of free public education in Pennsylvania, national Republican leader in the struggles against slavery in the United States and intrepid mainstay of the attempt to secure racial justice for the freedmen during Reconstruction, the only member of the House of Representatives ever to have been known, as the 'dictator' of Congress."

Historians' views of Stevens have swung sharply since his death as interpretations of Reconstruction have changed. The Dunning School,

which viewed the period as a disaster because it violated American

traditions of republicanism and fair government, depicted Stevens as a

villain for his advocacy of harsh measures in the South, and this

characterization held sway for much of the early 20th Century. Stevens was born in Danville, Vermont, on April 4, 1792. His parents had arrived there from Methuen, Massachusetts, around 1786. He suffered from many hardships during his childhood, including a club foot.

The fate of his father Joshua Stevens, an alcoholic, profligate

shoemaker who was unable to hold a steady job, is uncertain. He may

have died at home, abandoned the family, or been killed in the War of 1812; in any case, he left his wife, Sally (Morrill) Stevens, and four small sons in dire poverty. Having completed his course of study at Peacham Academy, Stevens entered Dartmouth College as a sophomore in 1811, and graduated in 1814; before doing so, he spent one term and part of another at the University of Vermont. He then moved to York, Pennsylvania, where he taught school and studied law. After admission to the bar, he established a successful law practice, first in Gettysburg in 1816, then in Lancaster in 1842. He later took on several young lawyers, among them Edward McPherson, who later became his protégé and ardent supporter in Congress. Stevens

never married but two of his adult nephews came to live with him. He

shared his home and parental responsibilities with his mixed race

housekeeper of twenty years, Lydia Hamilton Smith, but historians are

unsure whether the relationship was sexual, as was widely rumored. At first, Stevens belonged to the Federalist Party, but switched to the Anti - Masonic Party, then to the Whig Party, and finally to the Republican Party. In 1833, he was elected on the Anti - Masonic ticket to the Pennsylvania House of Representatives, where he served intermittently until 1842. He

introduced legislation to curb secret societies, to provide more funds

to Pennsylvania's colleges, and to put a constitutional limit on state

debt. He refused to sign the new state constitution of 1838 because it

did not give the right to vote to black citizens. He also came to the

defense of a new state law, passed on April 1, 1834, providing free

public schools. Newly elected members of the Pennsylvania State Senate tried

to repeal the public education act, while the lower house tried to

preserve it. Although Stevens had been reelected with instructions to

favor repeal, in a great speech, he defended free public education and

persuaded the Pennsylvania Assembly to vote 2 - 1 in favor of keeping the

new law. Stevens devoted most of his enormous energies to the destruction of what he considered the Slave Power, that is the conspiracy he saw of slave owners to seize control of the federal government and block the progress of liberty. In 1848, while still a Whig party member, Stevens was elected to serve in the House of Representatives. He served in congress from 1849 to 1853, and then from 1859 until his death in 1868. He defended and supported Native Americans, Seventh - day Adventists, Mormons, Jews, Chinese, and women. However, the defense of runaway or fugitive slaves gradually began to consume the greatest amount of his time, until the abolition of slavery became his primary political and personal focus. He was actively involved in the Underground Railroad, assisting runaway slaves in getting to Canada. A

possible Underground Railroad site (which consists of a water cistern

that shows evidence of being modified for human habitation) has been

discovered under his office in Lancaster, PA. This office, along with

Lydia Smith's home, is located next to the new conference center in the

center of Lancaster; they may soon become a museum open to the public. During the American Civil War Stevens

was one of the three or four most powerful men in Congress, using his

slashing oratorical powers, his chairmanship of the Ways and Means Committee, and above all his single minded devotion to victory. His power grew during Reconstruction as he dominated the House and helped to draft both the Fourteenth Amendment and the Reconstruction Act in 1867. He was one of two Congressmen in July, 1861 opposing the Crittenden - Johnson Resolution stating

the limited war aim of restoring the Union while preserving slavery; he

helped repeal it in December. In August, 1861, he supported the first

law attacking slavery, the Confiscation Act that said owners would

forfeit any slaves they allowed to help the Confederate war effort. By

December he was the first Congressional leader pushing for emancipation

as a tool to weaken the rebellion. He called for total war on January

22, 1862: "Let

us not be deceived. Those who talk about peace in sixty days are

shallow statesmen. The war will not end until the government shall more

fully recognize the magnitude of the crisis; until they have discovered

that this is an internecine war in which one party or the other must be

reduced to hopeless feebleness and the power of further effort shall be

utterly annihilated. It is a sad but true alternative. The South can

never be reduced to that condition so long as the war is prosecuted on

its present principles. The North with all its millions of people and

its countless wealth can never conquer the South until a new mode of

warfare is adopted. So long as these states are left the means of

cultivating their fields through forced labor, you may expend the blood

of thousands and billions of money year by year, without being any

nearer the end, unless you reach it by your own submission and the ruin

of the nation. Slavery gives the South a great advantage in time of

war. They need not, and do not, withdraw a single hand from the

cultivation of the soil. Every able - bodied white man can be spared

for the army. The black man, without lifting a weapon, is the mainstay

of

the war. How, then, can the war be carried on so as to save the Union

and constitutional liberty? Prejudices may be shocked, weak minds

startled, weak nerves may tremble, but they must hear and adopt it.

Universal emancipation must be proclaimed to all. Those who now furnish

the means of war, but who are the natural enemies of slaveholders, must

be made our allies. If the slaves no longer raised cotton and rice,

tobacco and grain for the rebels, this war would cease in six months,

even though the liberated slaves would not raise a hand against their

masters. They would no longer produce the means by which they sustain

the war." Stevens

led the Radical Republican faction in their battle against the bankers

over the issuance of money during the Civil War. Stevens made various

speeches in Congress in favor of President Lincoln and Henry Carey's "Greenback" system, interest free currency in the form of fiat government issued United States Notes that

would effectively threaten the bankers' profits in being able to issue

and control the currency through fractional reserve loans. Stevens

warned that a debt based monetary system controlled by for-profit banks

would lead to the eventual bankruptcy of the people, saying "the Government and not the banks should have the benefit from creating the medium of exchange," yet

after Lincoln's assassination the Radical Republicans lost this battle

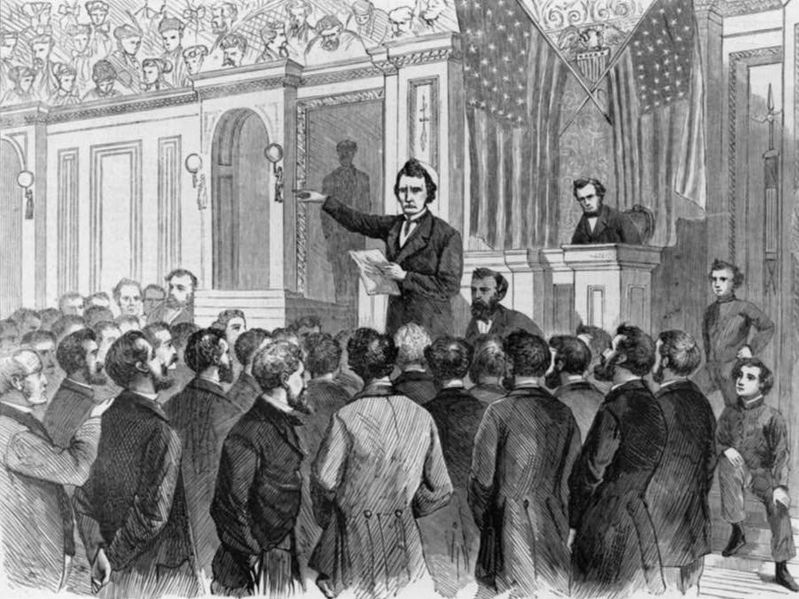

and a National banking monopoly emerged in the years after. Stevens was so outspoken in his condemnation of the Confederacy that Major General Jubal Early of the Army of Northern Virginia made a point of burning much of his iron business, at modern day Caledonia State Park to the ground during the Gettysburg Campaign. Early claimed that this action was in direct retaliation for Stevens' perceived support of similar atrocities by the Union Army in the South. Stevens was the leader of the Radical Republicans, who had full control of Congress after the 1866 elections. He largely set the course of Reconstruction.

He wanted to begin to rebuild the South, using military power to force

the South to recognize the equality of Freedmen. When President Johnson

resisted, Stevens proposed and passed the resolution for the impeachment of Andrew Johnson in 1868. Stevens told W.W. Holden, the Republican governor of North Carolina,

in December, 1866, "It would be best for the South to remain ten years

longer under military rule, and that during this time we would have

Territorial Governors, with Territorial Legislatures, and the

government at Washington would pay our general expenses as territories,

and educate our children, white and colored and both."

Thaddeus Stevens died at midnight on August 11, 1868, in

Washington, D.C., less than three months after the acquittal of Johnson by the Senate. Stevens' coffin lay in state inside the Capitol Rotunda, flanked by a Black Honor Guard (the Butler Zouaves from the District of Columbia). Twenty thousand people, one-half of whom were African - American, attended his funeral in Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

He chose to be buried in the Shreiner - Concord Cemetery because it was

the only cemetery that would accept people without regard to race. Stevens

wrote the inscription on his headstone that reads: "I repose in this

quiet and secluded spot, not from any natural preference for solitude,

but finding other cemeteries limited as to race, by charter rules, I

have chosen this that I might illustrate in my death the principles

which I advocated through a long life, equality of man before his

Creator." Stevens' monument is at the intersection of North Mulberry Street and West Chestnut Street in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Stevens dreamed of a socially just world, where unearned privilege did not exist. He believed from his personal experience that being different or having a different perspective can enrich society. He believed that differences among people should not be feared or oppressed but celebrated. In his will he left $50,000 to establish Stevens, a school for the relief and refuge of homeless, indigent orphans.

"They shall be carefully educated in the various branches of English

education and all industrial trades and pursuits. No preference shall

be shown on account of race or color in their admission or treatment. Neither poor Germans, Irish or Mahometan, nor any others on account their race or religion of their parents, shall be excluded. They shall be fed at the same table." This original bequest has now evolved into Thaddeus Stevens College of Technology.

The College continually strives to provide underprivileged individuals

with opportunities and to create an environment in which individual

differences are valued and nurtured. In

Washington, D.C., the Stevens Elementary School was built in 1868 as

one of the first publicly funded schools for black children. President Jimmy Carter's daughter, Amy Carter, attended the school. Other locations named in honor of Thaddeus Stevens includes the community of Stevens, Pennsylvania, Stevens County, Kansas, Thaddeus Stevens Elementary School in New Castle, Pennsylvania, and The Stevens School in Peacham, Vermont. Buildings

associated with Stevens are currently being restored by the Historic

Preservation Trust of Lancaster, PA, with an eye toward focusing on the

establishment of a $20 million dollar museum. These include his home,

law offices, and a nearby tavern. The effort also celebrates the

contributions of his housekeeper, Lydia Hamilton Smith, who was

involved in the underground railroad.

Austin Stoneman, the naive and fanatical congressman in D.W. Griffith's The Birth of a Nation, was modeled on Stevens. Additionally, he was portrayed as a villain in The Clansman, the second novel in the trilogy upon which "Birth of a Nation" was based. He was also portrayed (by Lionel Barrymore) as a villain and fanatic in Tennessee Johnson, the 1942 MGM film about the life of President Andrew Johnson. In May of 2011, Steven Spielberg cast Tommy Lee Jones to play Stevens in a film adaptation of the book Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln, by Doris Kearns Goodwin, currently titled Lincoln.