<Back to Index>

- Chemist Percy Lavon Julian, 1899

- Architect Donato Bramante, 1444

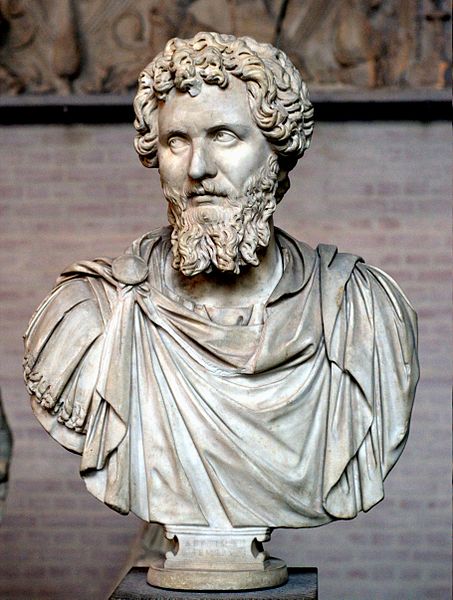

- Emperor of the Roman Empire Lucius Septimius Severus Augustus, 145

PAGE SPONSOR

Septimius Severus (Latin: Lucius Septimius Severus Augustus; 11 April 145 – 4 February 211), also known as Severus, was Roman Emperor from 193 to 211. Severus was born in Leptis Magna in the province of Africa. As a young man he advanced through the customary succession of offices under the reigns of Marcus Aurelius and Commodus. Severus seized power after the death of Emperor Pertinax in 193 during the Year of the Five Emperors. After deposing and killing the incumbent emperor Didius Julianus, Severus fought his rival claimants, the generals Pescennius Niger and Clodius Albinus. Niger was defeated in 194 at the Battle of Issus in Cilicia. Later that year Severus waged a short punitive campaign beyond the eastern frontier, annexing the Kingdom of Osroene as a new province. Severus defeated Albinus three years later at the Battle of Lugdunum in Gaul.

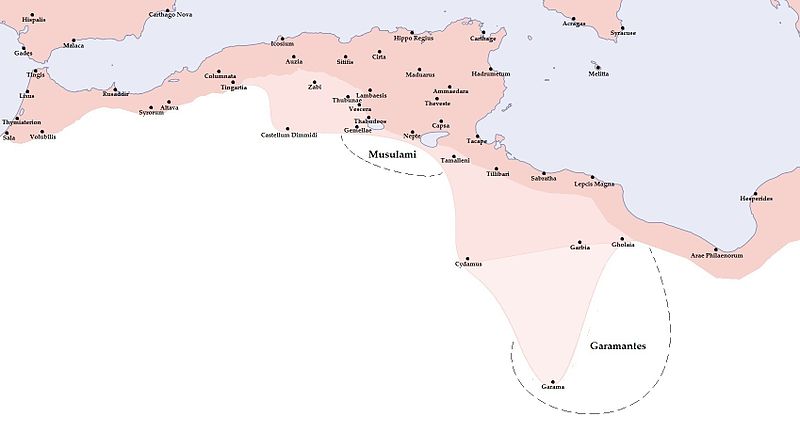

After solidifying his rule over the western provinces, Severus waged another brief, more successful war in the east against the Parthian Empire, sacking their capital Ctesiphon in 197 and expanding the eastern frontier to the Tigris. Furthermore, he enlarged and fortified the Limes Arabicus in Arabia Petraea. In 202, he campaigned in Africa and Mauretania against the Garamantes; capturing their capital Garama and expanding the Limes Tripolitanus along the southern frontier of the empire. Late in his reign he traveled to Britain, strengthening Hadrian's Wall and reoccupying the Antonine Wall. In 208 he began the conquest of Caledonia (modern Scotland), but his ambitions were cut short when he fell fatally ill in late 210. Severus died in early 211 at Eboracum, succeeded by his sons Caracalla and Geta. With the succession of his sons, Severus founded the Severan dynasty, the last dynasty of the empire before the Crisis of the Third Century. Septimius Severus was born on 11 April 145 at Leptis Magna (in modern Libya), son of Publius Septimius Geta and Fulvia Pia. Severus came from a wealthy, distinguished family of equestrian rank. He was of Italian Roman ancestry on his mother's side and of Punic or Libyan - Punic ancestry on his father's. Severus'

father was an obscure provincial who held no major political status,

but he had two cousins, Publius Septimius Aper and Gaius Septimius

Severus, who served as consuls under emperor Antoninus Pius. His mother's family had moved from Italy to North Africa and was of the Fulvius gens, an ancient and politically influential clan which was originally of plebeian status. Severus' siblings were an older brother, Publius Septimius Geta, and a younger sister, Septimia Octavilla. Severus’s maternal cousin was Praetorian prefect and consul Gaius Fulvius Plautianus. Septimius

Severus was brought up at his home town of Leptis Magna. He spoke the

local Punic language fluently but he was also educated in Latin and

Greek, which he spoke with a slight accent. Little else is known of the

young Severus' education but according to Cassius Dio, the boy had been eager for more education than he had actually got. Presumably, Severus received lessons in oratory, and at age 17, he gave his first public speech.

Sometime

around 162, Septimius Severus set out for Rome seeking a public career.

By recommendation of his 'uncle', Gaius Septimius Severus, he was

granted entry into the senatorial ranks by emperor

Marcus Aurelius. Membership of the senatorial order was a prerequisite to attain the standard succession of offices known as the cursus honorum,

and to gain entry into the Roman Senate. Nevertheless, it appears that

Severus' career during the 160s was beset with some difficulties. It is

likely that he served as a vigintivir in Rome, overseeing road maintenance in or near the city, and he may have appeared in court as an advocate. However, he omitted the military tribunate from the cursus honorum and was forced to delay his quaestorship until he had reached the required minimum age of 25. To make matters worse, the Antonine Plague swept

through the capital in 166. With his career at a halt, Severus decided

to temporarily return to Leptis, where the climate was healthier. According to the Historia Augusta,

a usually unreliable source, he was prosecuted for adultery during this

time but the case was ultimately dismissed. At the end of 169, Severus

was of the required age to become a quaestor and journeyed back to

Rome. On 5 December, he took office and was officially enrolled in the Roman Senate. Between

170 and 180 the activities of Septimius Severus went largely

unrecorded, in spite of the fact that he occupied an impressive number of posts in quick succession. The Antonine Plague had

severely thinned the senatorial ranks and with capable men now in short

supply, Severus' career advanced more steadily than it otherwise might

have. After his first term as quaestor, he was ordered to serve a

second term at Baetica (southern Spain), but

circumstances prevented Severus from taking up the appointment. The

sudden death of his father necessitated a return to Leptis Magna to

settle family affairs. Before he was able to leave Africa, Moorish tribesmen invaded southern Spain. Control of the province was handed over to the

emperor, while the Senate gained temporary control of Sardinia as compensation. Thus, Septimius Severus spent the remainder of his second term as quaestor on the island. In 173, Severus' kinsman Gaius Septimius Severus was appointed proconsul of the Africa Province. The elder Severus chose his cousin as one of his two legati pro praetore. Following the end of this term, Septimius Severus travelled back to Rome, taking up office as tribune of the plebs, with the distinction of being candidatus of the emperor.

Septimius

Severus was already in his early thirties at the time of his first

marriage. In about 175, he married a woman from Leptis Magna named

Paccia Marciana. It is likely that he met her during his tenure as legate under

his uncle. Marciana's name reveals that she was of Punic or Libyan

origin but virtually nothing else is known of her. Septimius Severus

does not mention her in his autobiography, though he later commemorated

her with statues when he became emperor. The Historia Augusta claims

that Marciana and Severus had two daughters but their existence is

nowhere else attested. It appears that the marriage produced no

children, despite lasting for more than ten years. Marciana died of natural causes around 186. Septimius

Severus was now in his forties and still childless. Eager to remarry,

he began enquiring into the horoscopes of prospective brides. The Historia Augusta relates

that he heard of a woman in Syria who had been foretold that she would

marry a king, and therefore Severus sought her as his wife. This woman was an Emesan noblewoman named Julia Domna. Her father, Julius Bassianus, descended from the royal house of Samsigeramus and Sohaemus, and served as a high priest to the local cult of the sun god Elagabal. Domna's older sister was Julia Maesa, later grandmother to the future emperors Elagabalus and Alexander Severus. Bassianus accepted Severus' marriage proposal in early 187, and the following summer he and Julia were married. The

marriage proved to be a happy one and Severus cherished his wife and

her political opinions, since she was very well read and keen on

philosophy. Together, they had two sons, Lucius Septimius Bassianus (later nicknamed Caracalla, b. 4 April 188) and Publius Septimius Geta (b. 7 March 189).

In 191 Severus received from the emperor

Commodus the command of the legions in Pannonia. On the murder of Pertinax by the Praetorian Guard in 193, Severus' troops proclaimed him Emperor at Carnuntum, whereupon he hurried to Italy. The former emperor, Didius Julianus,

was condemned to death by the Senate and killed, and Severus took

possession of Rome without opposition. He executed Pertinax's murderers

and dismissed the rest of the Praetorian Guard, populating its ranks with loyal troops from his own legions. The legions of Syria, however, had proclaimed Pescennius Niger emperor. At the same time, Severus felt it was reasonable to offer Clodius Albinus, the powerful governor of Britannia who had probably supported Didius against him, the rank of Caesar, which implied some claim to succession. With his rearguard safe, he moved to the East and crushed Niger's forces at the Battle of Issus.

The following year was devoted to suppressing Mesopotamia and other

Parthian vassals who had backed Niger. When afterwards Severus declared openly his son Caracalla as

successor, Albinus was hailed emperor by his troops and moved to

Gallia. Severus, after a short stay in Rome, moved northwards to meet

him. On February 19, 197, in the Battle of Lugdunum, with an army of about 75,000 men, mostly composed of Illyrian, Moesian and Dacian legions, Severus defeated and killed Clodius Albinus, securing his full control over the Empire. In early 197 he departed Rome and travelled to the east by sea. He embarked at Brundisium and probably landed at the port of Aegeae in Cilicia, traveling to Syria by land. He immediately gathered his army and crossed the Euphrates. Abgar IX, King of Osroene but essentially only the ruler of Edessa since

the annexation of his kingdom as a Roman province, handed over his

children as hostages and assisted Severus' expedition by providing

archers. At this time Tiridates II, King of Armenia, also sent hostages, money and gifts. Severus traveled onwards to Nisibis, which his general Julius Laetus had prevented from falling into enemy hands. Afterwards, Severus returned to Syria for a time to plan a much more ambitious campaign. The

following year he led another, more successful campaign against the

Parthian Empire, reportedly in retaliation for the support given to

Pescennius Niger. The Parthian capital Ctesiphon was sacked by the legions and the northern half of Mesopotamia was annexed to the empire. However, like Trajan over a century before, he was unable to capture the fortress of Hatra even after two lengthy sieges. During his time in the east he also expanded the Limes Arabicus, building new fortifications in the Arabian Desert from Basie to Dumata. His relations with the Roman Senate were

never good. He was unpopular with them from the outset, having seized

power with the help of the military, and he returned the sentiment.

Severus ordered the execution of dozens of Senators on charges of

corruption and conspiracy against him, replacing them with his own favorites. Upon his arrival at Rome in 193, he discharged the Praetorian Guard which

had murdered Pertinax and auctioned the Roman Empire to Didius

Julianus. Its members were stripped of their ceremonial armour and

ordered to remove themselves within 100 miles of the city on pain of

death. Severus then raised a new Guard composed of 50,000 loyal soldiers mainly camped at Albanum,

near Rome (also probably to grant the emperor a kind of centralized

reserve). During his reign the number of legions was also increased

from 25/30 to 33. He also increased the number of auxiliary corps (numerii), many of these troops coming from the Eastern borders. Additionally the annual wage for a soldier was raised from 300 to 500 denarii. Although his actions turned Rome into a military dictatorship,

he was popular with the citizens of Rome, having stamped out the

rampant corruption of Commodus's reign. When he returned from his

victory over the Parthians, he erected the Arch of Septimius Severus in Rome. According to Cassius Dio, however, after 197 Severus fell heavily under the influence of his Praetorian Prefect, Gaius Fulvius Plautianus, who came to have almost total control of most branches of the imperial administration. Plautianus's daughter, Fulvia Plautilla,

was married to Severus's son, Caracalla. Plautianus’s excessive power

came to an end in 205, when he was denounced by the Emperor's dying

brother and killed. However, the two following praefecti, including the jurist Aemilius Papinianus, received even larger powers.

Christians were persecuted during

the reign of Septimius Severus. Severus allowed the enforcement of

policies already long established, which meant that Roman authorities

did not intentionally seek out Christians, but when people were accused

of being Christians they would be forced to either curse Jesus and make an offering to Roman gods, or be executed. Furthermore, wishing to strengthen the peace by encouraging religious harmony through syncretism, Severus tried to limit the spread of the two groups who refused to yield to syncretism by outlawing conversions to Christianity or Judaism.

Individual officials availed themselves of the laws to proceed with

rigor against the Christians. Naturally the emperor, with his strict

conception of law, did not hinder such partial persecution, which took

place in Egypt and the Thebaid, as well as in Africa proconsularis and the East. Christian martyrs were numerous in Alexandria. No less severe were the persecutions in Africa, which seem to have begun in 197 or 198, and included the Christians known in the Roman martyrology as the martyrs of Madaura. Probably in 202 or 203 Felicitas and Perpetua suffered for their faith. Persecution again raged for a short time under the proconsul Scapula in 211, especially in Numidia and Mauritania. Later accounts also speak of a Gallic persecution, especially at Lyons,

under Severus, but historians, based on archaeological and literary

evidence, generally consider these events actually to have taken place

under Emperor Marcus Aurelius. In late 202 Severus launched a campaign in the province of Africa. The legate of Legio III Augusta Quintus Anicius Faustus had been fighting against the Garamantes along the Limes Tripolitanus for five years, capturing several settlements from the enemy such as Cydamus, Gholaia, Garbia, and their capital Garama - over 600 km south of Leptis Magna. During this time the province of Numidia was also enlarged: the empire annexed the settlements of Vescera, Castellum Dimmidi, Gemellae, Thabudeos, Thubunae, and Zabi. By 203 the entire southern frontier of Roman Africa had been dramatically

expanded and re-fortified. Desert nomads could no longer safely raid

the region's interior and escape back into the Sahara. In 208 Severus traveled to Britain with the intention of conquering Caledonia. Modern archaeological discoveries have made the scope and direction of his northern campaign better understood. Severus

likely arrived in Britain possessing an army over 40,000, considering

some of the camps constructed during his campaign could house this

number. He strengthened Hadrian's Wall and reconquered the Southern Uplands up to the Antonine Wall, which was also enhanced. Severus built a 165 acre camp south of the Antonine Wall at Trimontium,

likely assembling his forces there. Severus then thrust north with his

army across the wall into enemy territory. Retracing the steps of Agricola over a century previously, Severus rebuilt and garrisoned many abandoned Roman forts along the east coast, including Carpow which could house up to 40,000 soldiers. An

interesting story from around this time is when Severus' wife, Julia

Domna, criticised the sexual morals of the Caledonian women, the wife

of Caledonian chief Argentocoxos replied: "We fulfill the demands of

nature in a much better way than do you Roman women; for we consort

openly with the best men, whereas you let yourselves be debauched in

secret by the vilest". Cassius

Dio's account of the invasion reads "Severus, accordingly, desiring to

subjugate the whole of it, invaded Caledonia. But as he advanced

through the country he experienced countless hardships in cutting down

the forests, levelling the heights, filling up the swamps, and bridging

the rivers; 2 but he fought no battle and beheld no enemy in battle

array. The enemy purposely put sheep and cattle in front of the

soldiers for them to seize, in order that they might be lured on still

further until they were worn out; for in fact the water caused great

suffering to the Romans, and when they became scattered, they would be

attacked. Then, unable to walk, they would be slain by their own men,

in order to avoid capture, so that a full fifty thousand died. 3 But

Severus did not desist until he approached the extremity of the island.

Here he observed most accurately the variation of the sun's motion and

the length of the days and the nights in summer and winter

respectively. 4 Having thus been conveyed through practically the whole

of the hostile country (for he actually was conveyed in a covered

litter most of the way, on account of his infirmity), he returned to

the friendly portion, after he had forced the Britons to come to terms,

on the condition that they should abandon a large part of their

territory." By

210, Severus' campaigning had made significant gains, despite

Caledonian guerrilla tactics and purportedly heavy Roman casualties.

The Caledonians sued for peace, which Severus granted on condition they

relinquish control of the Central Lowlands. This is evidenced by extensive Severan era fortifications in the Central Lowlands. The Caledonians, short on supplies and feeling their position becoming desperate, revolted later that year along with the Maeatae. Severus

prepared for another protracted campaign within Caledonia. He was now

intent on exterminating the Caledonians, telling his soldiers: “Let no

one escape sheer destruction, No one our hands, not even the babe in

the womb of the mother, If it be male; let it nevertheless not escape

sheer destruction.” Severus' campaign was cut short when he fell fatally ill. He

withdrew to Eboracum and died there in 211. Although his son Caracalla

continued campaigning the following year, he soon settled for peace.

The Romans never campaigned deep into Caledonia again: they soon withdrew south permanently to Hadrian's Wall. He

is famously said to have given the advice to his sons: "Be harmonious,

enrich the soldiers, and scorn all other men" before he died at Eboracum (York) on February 4, 211. Upon his death in 211, Severus was deified by the Senate and succeeded by his sons, Caracalla and Geta, who were advised by his wife Julia Domna. The cameo glass Portland Vase is said to have been excavated in the 16th century from his tomb. Though

his military expenditure was costly to the empire, Severus was the

strong, able ruler that Rome needed at the time. His enlargement of the Limes Tripolitanus secured Africa, the agricultural base of the empire. His victory over Parthia was total, establishing a new status quo in the east which secured Nisibis and Singara for the empire. His policy of an expanded and better rewarded army was criticized by his contemporary Dio Cassius and Herodianus:

in particular, they pointed out the increasing burden (in the form of

taxes and services) the civilian population had to bear to maintain the

new army. In order to maintain his enlarged military he debased the Roman currency drastically. Upon his accession he decreased the silver purity of the denarius from

81.5% to 78.5%. However, the silver weight actually increased, rising

from 2.40 grams to 2.46 grams. Nevertheless the following

year he debased the denarius substantially because of rising military

expenditures. The silver purity decreased from 78.5% to 64.5% — the

silver weight dropping from 2.46 grams to 1.98 grams. In 196

he reduced the purity and silver weight of the denarius again, to 54%

and 1.82 grams respectively. Severus' currency debasement was the largest since the reign of Nero, compromising the long term strength of the economy. However, Severus

minted a much higher volume of denarii than his predecessors, alleviating some of the negative effects of debasement. Severus

was also distinguished for his buildings. Apart from the triumphal arch

in the Roman Forum carrying his full name, he also built the Septizodium in Rome and enriched greatly his native city of Leptis Magna (including another triumphal arch on the occasion of his visit of 203). The greater part of the Flavian Palace overlooking the Circus Maximus was undertaken in his reign.