<Back to Index>

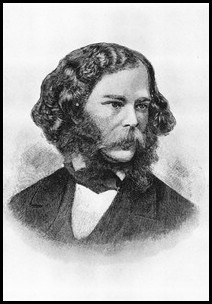

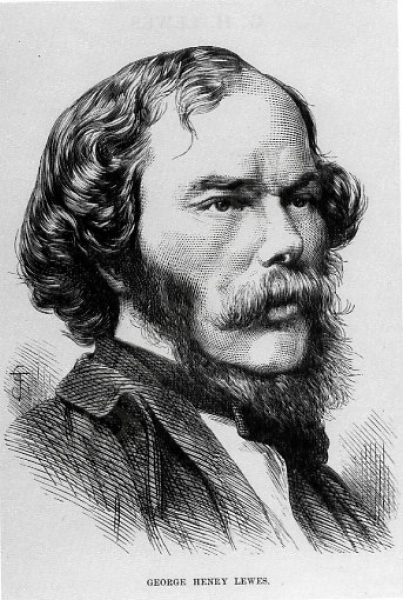

- Philosopher George Henry Lewes, 1817

- Painter George Clausen, 1852

- Sultan of the Ottoman Empire Ahmed I (Bakhti), 1590

PAGE SPONSOR

George Henry Lewes (18 April 1817 – 28 November 1878) was an English philosopher and critic of literature and theatre. He became part of the mid Victorian ferment of ideas which encouraged discussion of Darwinism, positivism, and religious scepticism. However, he is perhaps best known today for having openly lived with George Eliot, a soul mate whose life and writings were enriched by their friendship, although they were never married.

Lewes, born in London, was an illegitimate son of a minor poet, John Lee Lewes, and Elizabeth Ashweek and grandson of comic actor Charles Lee Lewes. His mother married a retired sea captain when he was six and frequent changes of home meant he was educated in London, Jersey, Brittany, and finally at Dr Charles Burney's school in Greenwich. Having abandoned successively a commercial and a medical career, he seriously thought of becoming an actor and appeared several times on stage between 1841 and 1850. Finally he devoted himself to literature, science and philosophy.

As early as 1836 he belonged to a club formed for the study of philosophy, and had sketched out a physiological treatment of the philosophy of the Scottish school. Two years later he went to Germany, probably with the intention of studying philosophy.

He became friends with Leigh Hunt, and through him, entered London literary society and met John Stuart Mill, Thomas Carlyle and Charles Dickens.

In 1841 he married Agnes Jervis, daughter of Swynfen Stevens Jervis. Lewes met writer Marian Evans, later to be famous as George Eliot, in 1851, and by 1854 they had decided to live together. Lewes and Agnes Jervis had agreed to have an open marriage, and

in addition to the three children they had together, Agnes had also had

several children by other men. Since Lewes was named on the birth

certificate as the father of one of these children despite knowing this

to be false, and was therefore considered complicit in adultery, he was

not able to divorce Agnes. In July 1854 Lewes and Evans travelled to Weimar and Berlin together for the purpose of research. The

trip to Germany also served as a honeymoon as Evans and Lewes were now

effectively married, with Evans calling herself Marian Evans Lewes, and

referring to Lewes as her husband. It was not unusual for men in

Victorian society to have affairs; Charles Dickens, Friedrich Engels and Wilkie Collins had

committed relationships with women they were not married to, though

more discreetly than Lewes. What was scandalous was the Leweses' open

admission of the relationship. Of his three sons only one, Charles Lewes, survived him; he became a London county councillor. During

the next ten years Lewes supported himself by contributing, to

quarterly and other reviews, articles discussing a wide range of

subjects, often imperfect but revealing acute critical judgment

enlightened by philosophic study. The most valuable are those on drama, afterwards republished under the title Actors and Acting (1875), and The Spanish Drama (1846). As a youngster, he witnessed a performance by Edmund Kean which stayed with him as an unforgettable experience. He also witnessed and wrote of his impressions of performances by William Charles Macready and

other famous stars of the 19th century London stage. He is considered

to be the first practitioner of modern theatre criticism and the

realistic approach to acting. In 1845 – 46, Lewes published The Biographical History of Philosophy,

an attempt to depict the life of philosophers as an ever renewed

fruitless labour to attain the unattainable. In 1847 – 48, he published

two novels — Ranthrope, and Rose, Blanche and Violet —

which, though displaying considerable skill in plot, construction, and

characterization, have taken no permanent place in literature. The same

is to be said of an ingenious attempt to rehabilitate Robespierre (1849). In 1850 he collaborated with Thornton Leigh Hunt in the foundation of the Leader, of which he was the literary editor. In 1853 he republished under the title of Comte's Philosophy of the Sciences a series of papers which had appeared in that journal. The culmination of Lewes's work in prose literature is the Life of Goethe (1855),

probably the best known of his writings. Lewes's versatility, and his

combination of scientific with literary tastes, eminently fitted him to

appreciate the wide ranging activity of the German poet. The work

became well known in Germany itself, despite the boldness of its

criticism and the unpopularity of some of its views (e.g. on the

relation of the second to the first part of Faust).

From

about 1853 Lewes's writings show that he was occupying himself with

scientific and more particularly biological work, though he always

showed a distinctly scientific bent in his writings. Considering that

he had not had technical training these studies are a testimony to his

intellect. More than popular expositions of accepted scientific truths,

they contain able criticisms of conventionally accepted ideas and

embody the results of individual research and individual reflection. He

made several suggestions, some of which have since been accepted by physiologists,

of which the most valuable is that now known as the doctrine of the

functional indifference of the nerves — that what were known as the

specific energies of the optic, auditory and other nerves are simply

differences in their mode of action due to the differences of the

peripheral structures or sense - organs with which they are connected.

This idea was subsequently proposed independently by Wundt.

In 1865, on the starting of the

Fortnightly Review, Lewes became its editor, but he retained the post for less than two years, when he was succeeded by John Morley.

This marks the transition from more strictly scientific to philosophic

work. Lewes had been interested in philosophy from early youth; one of

his earliest essays was an appreciative account of Hegel's Aesthetics. Under the influence of the positivism of Auguste Comte and John Stuart Mill's System of Logic, he abandoned all faith in the possibility of metaphysics, and recorded this abandonment in his History of Philosophy.

Yet he did not at any time give unqualified assent to Comte's

teachings, and with wider reading and reflection his mind moved further

away from the positivist stance. In the preface to the third edition of

his History of Philosophy he avowed a change in this direction, and this movement is even more plainly discernible in subsequent editions of the work. The final outcome of his intellectual progress is The Problems of Life and Mind.

His sudden death cut short the work, yet it is complete enough to allow

a judgment on the author's matured conceptions on biological,

psychological and metaphysical problems. The first two volumes on The Foundations of a Creed laid down Lewes' foundation — a rapprochement between

metaphysics and science. He was still positivist enough to pronounce

all inquiry into the ultimate nature of things fruitless: what matter,

form, and spirit are in themselves is a futile question that belongs to

the sterile region of "metempirics". But philosophical questions may be susceptible to a precise solution through scientific method.

Thus, since the relation of subject to object falls within our

experience, it is a proper matter for philosophic investigation. His

treatment of the question of the relation of subject to object confused

the scientific truth that mind and body coexist in the living organism

and the philosophic truth that all knowledge of objects implies a

knowing subject. In Shadworth Hodgson's phrase, he mixed up the genesis of mental forms with their nature (Philosophy of Reflexion, ii. 40-58). Thus he reached a monistic doctrine

that mind and matter are two aspects of the same existence by attending

simply to the parallelism between psychical and physical processes as a

given fact (or probable fact) of our experience, leaving out of account

their relation as subject and object in the cognitive act. His

identification of the two as phases of one existence is open to

criticism not only from the point of view of philosophy but from that

of science. In his treatment of such ideas as "sensibility,"

"sentience" and the like, he does not always make it clear whether he

is speaking of physical or of psychical phenomena. Among other

philosophic questions discussed in these two volumes the nature of

casual relation is perhaps the one which is handled with most freshness

and suggestiveness. The third volume, The Physical Basis of Mind, further develops the writer's views on organic activities

as a whole. He insists on the radical distinction between organic and

inorganic processes and the impossibility of explaining the former by

purely mechanical principles. All parts of the nervous system have the

same elementary property; sensibility. Thus sensibility belongs as much

to the lower centres of the spinal cord as to the brain, the former,

more elementary, form contributing to the subconscious region

of mental life, while the higher functions of the nervous system, which

make up our conscious mental life, are more complex modifications of

this fundamental property of nerve substance. The nervous organism acts as a whole, particular mental operations cannot be referred to definite regions of the brain, and the hypothesis of nervous activity by an isolated pathway from one nerve cell to

another is altogether illusory. By insisting on the complete coincidence between the regions of nerve action and sentience, that

these are but different aspects of one thing, he was able to attack the

doctrine of animal and human automatism which

affirms that feeling or consciousness is merely an incidental concomitant of nerve action in no way essential to the chain of

physical events. Lewes's views on psychology, partly explained in the earlier volumes of the Problems,

are more fully worked out in the last two (3rd series). He discussed

the method of psychology with much insight. Against Comte and his

followers he claimed a place for introspection in psychological

research. As well as this subjective method there must be an objective

one, a reference to nervous conditions and socio - historical data.

Biology would help explain mental functions such as feeling and

thinking, it would not help us to understand differences of mental

faculty in different races and stages of human development. The organic

conditions of these differences will probably for ever escape

detection, hence they can be explained only as the products of the

social environment. The relationship of mental phenomena to social and

historical conditions is probably Lewes's most important contribution to psychology. He

also emphasized the complexity of mental phenomena. Every mental state

is regarded as compounded of three factors in different proportions —

sensible affection, logical grouping and motor impulse. But Lewes's

work in psychology consists less in discoveries than in method. His

biological experience prepared him to view mind as a complex unity of

which the highest processes are identical with and evolved out of the

lower. Thus the operation of thought, or "the logic of signs," is a

more complicated form of the elementary operations of sensation and

instinct or "the logic of feeling." The last volume of the Problems illustrates

this position. It is a valuable repository of psychological facts, many

of them drawn from obscure regions of mental life and from abnormal

experience. To suggest and to stimulate the mind, rather than to supply

it with any complete system of knowledge, may be said to be Lewes's

service to philosophy. The exceptional rapidity and versatility of his

intelligence seems to account at once for the freshness in his way of

envisaging the subject matter of philosophy and psychology, and for the

want of satisfactory elaboration and of systematic co-ordination.