<Back to Index>

- Physicist Owen Willans Richardson, 1879

- Landscape Architect Frederick Law Olmsted, 1822

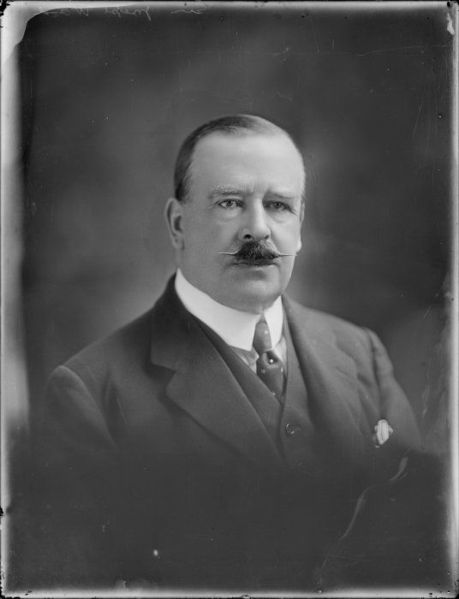

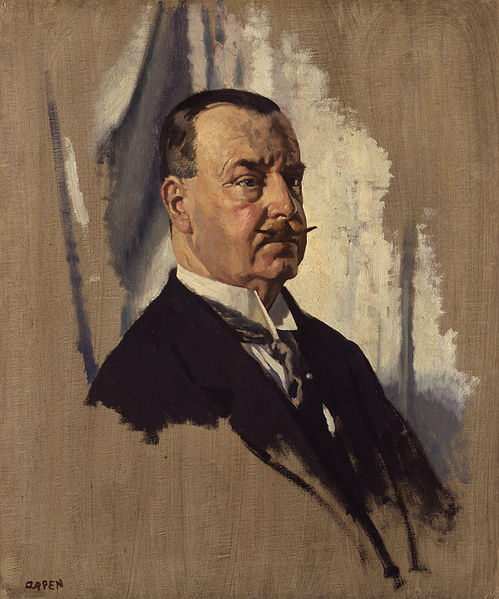

- Prime Minister of New Zealand Joseph George Ward, 1856

PAGE SPONSOR

Sir Joseph George Ward, 1st Baronet, GCMG (1856 – 1930) was the 17th Prime Minister of New Zealand on two occasions in the early 20th century.

Ward was born in Melbourne, on 26 April 1856. His family was of Irish descent, and Ward was raised as a Roman Catholic. His father, who is believed to have been an alcoholic, died in 1860, aged only 31 — Ward was raised by his mother, Hannah. In 1863, the family moved to Bluff (then officially known as Campbelltown), in New Zealand's Southland region, seeking better financial security — Hannah Ward established a shop and a boarding house.

Joseph

Ward received his formal education at primary schools in Melbourne and

Bluff. He did not go to secondary school. He did, however, read

extensively, and also picked up a good understanding of business from

his mother. He is described by most sources as highly energetic and

enthusiastic, and was keen to advance in the world — much of this

attitude is attributed to his mother, who was very eager to see her

children financially secure. In 1869, Ward found a job at the Post Office,

and later as a clerk. Later, with the help of a loan from his mother,

Ward began to work as a freelance trader, selling supplies to the

newly established Southland farming community. Ward

became involved in local politics very quickly. He was elected to the

Campbelltown (Bluff) Borough Council in 1878, despite being only 21

years old — he later became Mayor. He also served on the Bluff Harbour

Board, which he eventually became chairman of. In 1887, Ward successfully stood for Parliament, winning the seat of Awarua. Politically, Ward was a supporter of politicians such as Julius Vogel and Robert Stout, leaders of the liberal wing of Parliament — Ward's support was unusual in the far south. Ward became known as a strong debater on economic matters. In 1891, when the newly founded Liberal Party came to power, the new Prime Minister, John Ballance, appointed Ward to the position of Postmaster General. Later, when Richard Seddon became Prime Minister after Ballance's death, Ward became Treasurer (Minister of Finance).

Ward's basic political outlook was that the state existed to support

and promote private enterprise, and his conduct as Treasurer reflects

this. Ward's

increasing occupation with government affairs led to neglect of his own

business interests, however, and Ward's personal finances began to

deteriorate. In 1896, a judge declared Ward "hopelessly insolvent".

This placed Ward, as Treasurer, in a politically difficult situation,

and he was forced to resign his portfolios on 16 June. In 1897, he was

forced to file for bankruptcy, which legally obligated him to resign

his seat in Parliament. A loophole, however, meant that there was

nothing to stop him simply contesting it again — he did so, and in the

resulting by-election was

elected with an increased majority. Ward actually gained considerable

popularity as a result of his financial troubles — Ward was widely seen

as a great benefactor of the Southland region, and public perceptions

were that he was being persecuted by his enemies over an honest mistake. Gradually,

Ward rebuilt his businesses, and paid off his creditors. Richard

Seddon, still Prime Minister, quickly reappointed Ward to Cabinet. He

gradually emerged as the most prominent of Seddon's supporters, and was

seen as a possible successor. As Seddon's long tenure as Prime Minister

continued, some suggested that Ward should challenge Seddon for the

leadership, but Ward was unwilling. In 1906, Seddon unexpectedly died. Ward was in London at

the time. It was generally agreed in the party that Ward would succeed him, although the return journey would take two months — William Hall - Jones became Prime Minister until Ward arrived. Ward was sworn in on 6 August 1906. Ward

was not seen by most as being of the same calibre as Seddon. The

diverse interests of the Liberal Party, many believed, had been held

together only by Seddon's strength of personality and his powers of

persuasion — Ward was not seen as having the same qualities. Frequent

internal disputes led to indecision and frequent policy changes, with

the ultimate result being paralysis of government. The Liberal Party's

two main support bases, the left leaning urban workers and the

conservative small farmers, were increasingly at odds, and Ward lacked

any coherent strategy to solve the problem — any attempt to please one

group simply alienated the other. Ward increasingly focused on foreign

affairs, which was seen by his opponents as a sign that he could not

cope with the country's problems. In the 1908 elections, the Liberals won a majority, but in the 1911 elections, Parliament appeared to be deadlocked. The Liberals survived for a time on the casting vote of the Speaker, but Ward, discouraged by the result, resigned from the premiership in March the following year. The party replaced him with Thomas Mackenzie, his Minister of Agriculture — Mackenzie's government survived only a few more months. Ward, who most believed had finished his political career, took a position on the backbenches,

and refused several requests to resume the leadership of the

disorganised Liberals. He occupied himself with relatively minor

matters, and took his family on a visit to England, where he was

created a baronet by King George V on 20 June 1911. On

11 September 1913, however, Ward finally accepted the leadership of the

Liberal Party once again. Ward extracted a number of important

concessions from the party, insisting on a very high level of personal

control — Ward felt that the party's previous lack of direction was the

primary cause for its failure. Ward also worked to build alliances with

the growing labour movement, which was now standing candidates in many

seats. On 12 August 1915, Ward and accepted a proposal by William Massey and the governing Reform Party to form a joint administration for World War I.

Ward became deputy leader of the administration, also holding the

Finance portfolio. Relations between Ward and Massey were not good —

besides their political differences, Ward was an Irish Catholic, and

Massey was an Irish Protestant. The administration ended on 21 August

1919. In the 1919 elections, Ward himself lost the seat of Awarua, and left Parliament. In 1923, he contested a by-election in Tauranga, but was defeated by an unimportant Reform Party candidate, Charles MacMillan. Ward was largely considered a spent force. In the 1925 elections, however, he narrowly returned to Parliament as MP for Invercargill.

Ward contested the seat under the "Liberal" label, despite the fact

that the remnants of the Liberal Party were now calling themselves by

different names — his opponents characterised him as living in the

past, and of attempting to fight the same battles over again. Ward's

health was also failing. In 1928, however, the remnants of the Liberal Party reasserted themselves as the new United Party, focused around George Forbes (leader of one faction of the Liberals), Bill Veitch (leader of another faction), and Albert Davy (a

former organiser for the Reform Party). Forbes and Veitch both sought

the leadership, and neither of them gained a clear advantage. In the

end, Davy invited Ward himself to step in as a compromise candidate,

perhaps hoping that Ward's status as a former Prime Minister would

create a sense of unity. Ward

accepted the offer, and became leader of the new United Party. His

health, however, was still poor, and he found the task difficult. In the 1928 election campaign,

Ward startled both his supporters and his audience by promising to

borrow £70 million in the course of a year in order to revive the

economy — this is believed to have been a mistake caused by Ward's

failing eyesight. Despite the strong objections his party had to this

"promise", it was sufficient to prompt a massive surge in support for

United — in the elections, United gained the same number of seats as

Reform. With the backing of the Labour Party, Ward became Prime Minister again, twenty - two years after his original appointment. Ward's

health continued to decline, however. He suffered a number of heart

attacks, and soon, it was George Forbes who was effectively running the

government. Ward was determined not to resign, however, and remained

Prime Minister well after he had lost the ability to perform that role.

Finally, on 28 May 1930, Ward succumbed to strong pressure from his

colleagues and his family, and passed the premiership to Forbes. Ward died shortly afterwards, on 8 July. He was given a state funeral by way of a requiem mass celebrated by Archbishop Redwood at the Basilica of the Sacred Heart, Hill St, Wellington. He was buried with considerable ceremony in Bluff. His son Vincent, was elected to replace him as MP for Invercargill.