<Back to Index>

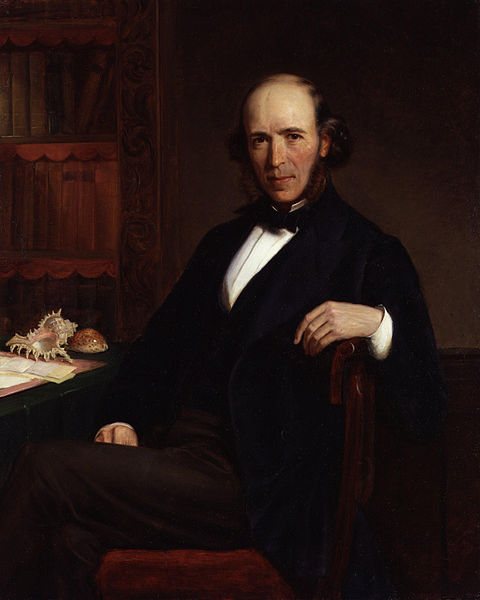

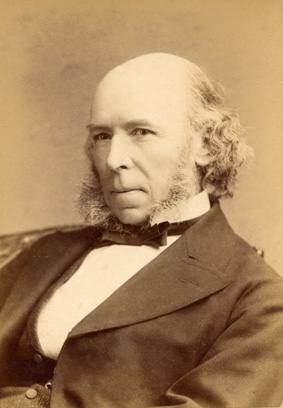

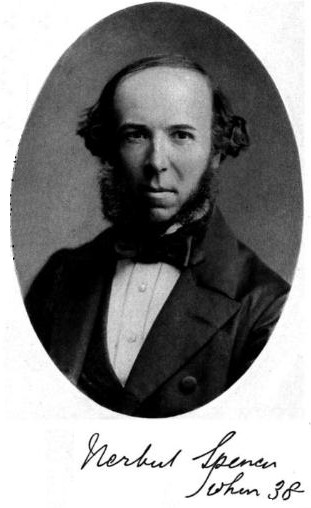

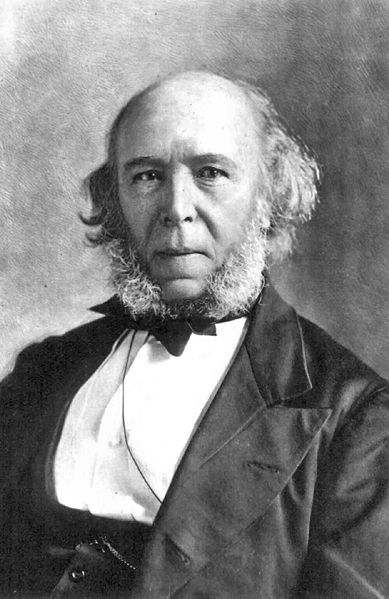

- Philosopher Herbert Spencer, 1820

- Composer Abraham Louis Niedermeyer, 1802

- Generaloberst of the Prussian Army Hans Hartwig von Beseler, 1850

PAGE SPONSOR

Herbert Spencer (27 April 1820 – 8 December 1903) was an English philosopher, biologist, sociologist, and prominent classical liberal political theorist of the Victorian era.

Spencer developed an all-embracing conception of evolution as the progressive development of the physical world, biological organisms, the human mind, and human culture and societies. He was "an enthusiastic exponent of evolution" and even "wrote about evolution before Darwin did." As a polymath, he contributed to a wide range of subjects, including ethics, religion, anthropology, economics, political theory, philosophy, biology, sociology, and psychology. During his lifetime he achieved tremendous authority, mainly in English speaking academia. "The only other English philosopher to have achieved anything like such widespread popularity was Bertrand Russell, and that was in the 20th century." Spencer was "the single most famous European intellectual in the closing decades of the nineteenth century" but his influence declined sharply after 1900; "Who now reads Spencer?" asked Talcott Parsons in 1937.

Spencer is best known for coining the concept "survival of the fittest", which he did in Principles of Biology (1864), after reading Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species. This term strongly suggests natural selection, yet as Spencer extended evolution into realms of sociology and ethics, he also made use of Lamarckism.

Herbert Spencer was born in Derby, England, on 27 April 1820, the son of William George Spencer (generally called George). Spencer’s father was a religious dissenter who drifted from Methodism to Quakerism, and who seems to have transmitted to his son an opposition to all forms of authority. He ran a school founded on the progressive teaching methods of Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi and also served as Secretary of the Derby Philosophical Society, a scientific society which had been founded in the 1790s by Erasmus Darwin, the grandfather of Charles.

Spencer was educated in empirical science by his father, while the members of the Derby Philosophical Society introduced him to pre-Darwinian concepts of biological evolution, particularly those of Erasmus Darwin and Jean - Baptiste Lamarck. His uncle, the Reverend Thomas Spencer, vicar of Hinton Charterhouse near Bath, completed Spencer’s limited formal education by teaching him some mathematics and physics, and enough Latin to enable him to translate some easy texts. Thomas Spencer also imprinted on his nephew his own firm free trade and anti - statist political views. Otherwise, Spencer was an autodidact who acquired most of his knowledge from narrowly focused readings and conversations with his friends and acquaintances.

As both an adolescent and a young man Spencer found it difficult to settle to any intellectual or professional discipline. He worked as a civil engineer during the railway boom of the late 1830s, while also devoting much of his time to writing for provincial journals that were nonconformist in their religion and radical in their politics. From 1848 to 1853 he served as sub-editor on the free trade journal The Economist, during which time he published his first book, Social Statics (1851), which predicted that humanity would eventually become completely adapted to the requirements of living in society with the consequential withering away of the state.

Its publisher, John Chapman, introduced him to his salon which was attended by many of the leading radical and progressive thinkers of the capital, including John Stuart Mill, Harriet Martineau, George Henry Lewes and Mary Ann Evans (George Eliot), with whom he was briefly romantically linked. Spencer himself introduced the biologist Thomas Henry Huxley, who would later win fame as 'Darwin’s Bulldog' and who remained his lifelong friend. However it was the friendship of Evans and Lewes that acquainted him with John Stuart Mill’s A System of Logic and with Auguste Comte’s positivism and which set him on the road to his life’s work. He strongly disagreed with Comte.

The first fruit of his friendship with Evans and Lewes was Spencer's second book, Principles of Psychology, published in 1855, which explored a physiological basis for psychology. The book was founded on the fundamental assumption that the human mind was subject to natural laws and that these could be discovered within the framework of general biology. This permitted the adoption of a developmental perspective not merely in terms of the individual (as in traditional psychology), but also of the species and the race. Through this paradigm, Spencer aimed to reconcile the associationist psychology of Mill’s Logic, the notion that human mind was constructed from atomic sensations held together by the laws of the association of ideas, with the apparently more 'scientific' theory of phrenology, which located specific mental functions in specific parts of the brain.

Spencer argued that both these theories were partial accounts of the truth: repeated associations of ideas were embodied in the formation of specific strands of brain tissue, and these could be passed from one generation to the next by means of the Lamarckian mechanism of use - inheritance. The Psychology, he believed, would do for the human mind what Isaac Newton had done for matter. However, the book was not initially successful and the last of the 251 copies of its first edition was not sold until June 1861.

Spencer's interest in psychology derived from a more fundamental concern which was to establish the universality of natural law. In common with others of his generation, including the members of

Chapman's salon, he was possessed with the idea of demonstrating that

it was possible to show that everything in the universe — including human

culture, language, and morality — could be explained by laws of universal

validity. This was in contrast to the views of many theologians of the

time who insisted that some parts of creation, in particular the human

soul, were beyond the realm of scientific investigation. Comte's Systeme de Philosophie Positive had

been written with the ambition of demonstrating the universality of

natural law, and Spencer was to follow Comte in the scale of his

ambition. However, Spencer differed from Comte in believing it was

possible to discover a single law of universal application which he

identified with progressive development and was to call the principle

of evolution. In

1858 Spencer produced an outline of what was to become the System of

Synthetic Philosophy. This immense undertaking, which has few parallels

in the English language, aimed to demonstrate that the principle of

evolution applied in biology, psychology, sociology (Spencer

appropriated Comte's term for the new discipline) and morality. Spencer

envisaged that this work of ten volumes would take twenty years to

complete; in the end it took him twice as long and consumed almost all

the rest of his long life. Despite

Spencer's early struggles to establish himself as a writer, by the

1870s he had become the most famous philosopher of the age. His

works were widely read during his lifetime, and by 1869 he was able to

support himself solely on the profit of book sales and on income from

his regular contributions to Victorian periodicals which were collected

as three volumes of Essays.

His works were translated into German, Italian, Spanish, French,

Russian, Japanese and Chinese, and into many other languages and he was

offered honors and awards all over Europe and North America. He also

became a member of the Athenaeum, an exclusive Gentleman's Club in London open only to those distinguished in the arts and sciences, and the X Club, a dining club of nine founded by T.H. Huxley that

met every month and included some of the most prominent thinkers of the

Victorian age (three of whom would become presidents of the Royal Society). Members included physicist - philosopher John Tyndall and Darwin's cousin, the banker and biologist Sir John Lubbock. There were also some quite significant satellites such as liberal clergyman Arthur Stanley, the Dean of Westminster; and guests such as Charles Darwin and Hermann von Helmholtz were

entertained from time to time. Through such associations, Spencer had a

strong presence in the heart of the scientific community and was able

to secure an influential audience for his views. Despite his growing wealth and fame he never owned a house of his own. The

last decades of Spencer's life were characterized by growing

disillusionment and loneliness. He never married, and after 1855 was a

perpetual hypochondriac who complained endlessly of pains and maladies

that no physician could diagnose. By

the 1890s his readership had begun to desert him while many of his

closest friends died and he had come to doubt the confident faith in

progress that he had made the centerpiece of his philosophical system.

His later years were also ones in which his political views became

increasingly conservative. Whereas Social Statics had

been the work of a radical democrat who believed in votes for women

(and even for children) and in the nationalization of the land to break

the power of the aristocracy, by the 1880s he had become a staunch

opponent of female suffrage and made common cause with the landowners

of the Liberty and Property Defence League against what they saw as the drift towards 'socialism' of elements (such as Sir William Harcourt) within the administration of William Ewart Gladstone -

largely against the opinions of Gladstone himself. Spencer's political

views from this period were expressed in what has become his most

famous work, The Man versus the State. The exception to Spencer's growing conservativism was that he remained throughout his life an ardent opponent of imperialism and militarism. His critique of the Boer War was especially scathing, and it contributed to his declining popularity in Britain. Spencer

also invented a precursor to the modern paper clip, though it looked

more like a modern cotter pin. This "binding - pin" was distributed by

Ackermann & Company. Spencer shows drawings of the pin in Appendix

I (following Appendix H) of his autobiography along with published

descriptions of its uses. In 1902, shortly before his death, Spencer was nominated for the Nobel Prize for literature.

He continued writing all his life, in later years often by dictation,

until he succumbed to poor health at the age of 83. His ashes are

interred in the eastern side of London's Highgate Cemetery facing Karl Marx's grave. At Spencer's funeral the Indian nationalist leader Shyamji Krishnavarma announced a donation of £1,000 to establish a lectureship at Oxford University in tribute to Spencer and his work.

The

basis for Spencer's appeal to many of his generation was that he

appeared to offer a ready made system of belief which could substitute

for conventional religious faith at a time when orthodox creeds were

crumbling under the advances of modern science. Spencer's philosophical

system seemed to demonstrate that it was possible to believe in the

ultimate perfection of humanity on the basis of advanced scientific

conceptions such as the

first law of thermodynamics and biological evolution. In essence Spencer's philosophical vision was formed by a combination of deism and

positivism. On the one hand, he had imbibed something of eighteenth

century deism from his father and other members of the Derby

Philosophical Society and from books like George Combe's immensely popular The Constitution of Man (1828).

This treated the world as a cosmos of benevolent design, and the laws

of nature as the decrees of a 'Being transcendentally kind.' Natural

laws were thus the statutes of a well governed universe that had been

decreed by the Creator with the intention of promoting human happiness.

Although Spencer lost his Christian faith as a teenager and later

rejected any 'anthropomorphic' conception of the Deity, he nonetheless

held fast to this conception at an almost sub-conscious level. At the

same time, however, he owed far more than he would ever acknowledge to

positivism, in particular in its conception of a philosophical system

as the unification of the various branches of scientific knowledge. He

also followed positivism in his insistence that it was only possible to

have genuine knowledge of phenomena and hence that it was idle to

speculate about the nature of the ultimate reality. The tension between

positivism and his residual deism ran through the entire System of

Synthetic Philosophy. Spencer

followed Comte in aiming for the unification of scientific truth; it

was in this sense that his philosophy aimed to be 'synthetic.' Like

Comte, he was committed to the universality of natural law, the idea

that the laws of nature applied without exception, to the organic realm

as much as to the inorganic, and to the human mind as much as to the

rest of creation. The first objective of the Synthetic Philosophy was

thus to demonstrate that there were no exceptions to being able to

discover scientific explanations, in the form of natural laws, of all

the phenomena of the universe. Spencer’s volumes on biology,

psychology, and sociology were all intended to demonstrate the

existence of natural laws in these specific disciplines. Even in his

writings on ethics, he held that it was possible to discover ‘laws’ of

morality that had the status of laws of nature while still having

normative content, a conception which can be traced to Combe’s Constitution of Man. The

second objective of the Synthetic Philosophy was to show that these

same laws led inexorably to progress. In contrast to Comte, who

stressed only the unity of scientific method, Spencer sought the

unification of scientific knowledge in the form of the reduction of all

natural laws to one fundamental law, the law of evolution. In this

respect, he followed the model laid down by the Edinburgh publisher Robert Chambers in his anonymous Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation (1844). Although often dismissed as a lightweight forerunner of Charles Darwin’s The Origin of Species, Chambers’ book was in reality a programme for the unification of science which aimed to show that Laplace’s nebular hypothesis for

the origin of the solar system and Lamarck’s theory of species

transformation were both instances (in Lewes' phrase) of 'one

magnificent generalization of progressive development.' Chambers was

associated with Chapman’s salon and his work served as the

unacknowledged template for the Synthetic Philosophy. The

first clear articulation of Spencer’s evolutionary perspective occurred

in his essay, 'Progress: Its Law and Cause', published in Chapman's Westminster Review in 1857, and which later formed the basis of the First Principles of a New System of Philosophy (1862). In it he expounded a theory of evolution which combined insights from Samuel Taylor Coleridge's essay 'The Theory of Life' — itself derivative from Friedrich von Schelling's Naturphilosophie — with a generalization of von Baer’s

law of embryological development. Spencer posited that all structures

in the universe develop from a simple, undifferentiated, homogeneity to

a complex, differentiated, heterogeneity, while being accompanied by a

process of greater integration of the differentiated parts. This

evolutionary process could be found at work, Spencer believed,

throughout the cosmos. It was a universal law, applying to the stars

and the galaxies as much as to biological organisms, and to human

social organization as much as to the human mind. It differed from

other scientific laws only by its greater generality, and the laws of

the special sciences could be shown to be illustrations of this

principle. This attempt to explain the evolution of complexity was radically different from that to be found in Darwin’s Origin of Species which was published two years later. Spencer is often, quite erroneously,

believed to have merely appropriated and generalized Darwin’s work on natural selection. But although after reading Darwin's work he coined the phrase 'survival of the fittest' as his own term for Darwin's concept, and

is often misrepresented as a thinker who merely applied the Darwinian

theory to society, he only grudgingly incorporated natural selection

into his preexisting overall system. The primary mechanism of species

transformation that he recognized was Lamarckian use - inheritance

which posited that organs are developed or are diminished by use or

disuse and that the resulting changes may be transmitted to future

generations. Spencer believed that this evolutionary mechanism was also

necessary to explain 'higher' evolution, especially the social

development of humanity. Moreover, in contrast to Darwin, he held that

evolution had a direction and an endpoint, the attainment of a final

state of equilibrium. He tried to apply the theory of biological

evolution to sociology. He proposed that society was the product of

change from lower to higher forms, just as in the theory of biological

evolution, the lowest forms of life are said to be evolving into higher

forms. Spencer claimed that man's mind had evolved in the same way from

the simple automatic responses of lower animals to the process of

reasoning in the thinking man. Spencer believed in two kinds of

knowledge: knowledge gained by the individual and knowledge gained by

the race. Intuition, or knowledge learned unconsciously, was the

inherited experience of the race. Spencer read with excitement the original positivist sociology of Auguste Comte. A philosopher of science, Comte had proposed a theory of sociocultural evolution that society progresses by a general law of three stages.

Writing after various developments in biology, however, Spencer

rejected what he regarded as the ideological aspects of Comte's

positivism, attempting to reformulate social science in terms of

evolutionary biology. One might broadly describe Spencer's sociology as socially Darwinistic (though strictly speaking he was a proponent of Lamarckism rather than Darwinism). The

evolutionary progression from simple, undifferentiated homogeneity to

complex, differentiated heterogeneity was exemplified, Spencer argued,

by the development of society. He developed a theory of two types of

society, the militant and the industrial, which corresponded to this

evolutionary progression. Militant society, structured around

relationships of hierarchy and obedience, was simple and

undifferentiated; industrial society, based on voluntary, contractually

assumed social obligations, was complex and differentiated. Society,

which Spencer conceptualized as a 'social organism'

evolved from the simpler state to the more complex according to the

universal law of evolution. Moreover, industrial society was the direct

descendant of the ideal society developed in Social Statics,

although Spencer now equivocated over whether the evolution of society

would result in anarchism (as he had first believed) or whether it

pointed to a continued role for the state, albeit one reduced to the

minimal functions of the enforcement of contracts and external defense. Though Spencer made some valuable contributions to early sociology, not least in his influence on structural functionalism,

his attempt to introduce Lamarckian or Darwinian ideas into the realm

of social science was unsuccessful. It was considered by many, furthermore, to be actively dangerous. Hermeneuticians of the period, such as Wilhelm Dilthey, would pioneer the distinction between the natural sciences (Naturwissenschaften) and human sciences (Geisteswissenschaften). In the 1890s, Émile Durkheim established formal academic sociology with a firm emphasis on practical social research. By the turn of the 20th century the first generation of German sociologists, most notably Max Weber, had presented methodological antipositivism. The

end point of the evolutionary process would be the creation of 'the

perfect man in the perfect society' with human beings becoming

completely adapted to social life, as predicted in Spencer’s first

book. The chief difference between Spencer’s earlier and later

conceptions of this process was the evolutionary timescale involved.

The psychological — and hence also the moral — constitution which had

been

bequeathed to the present generation by our ancestors, and which we in

turn would hand on to future generations, was in the process of gradual

adaptation to the requirements of living in society. For example,

aggression was a survival instinct which had been necessary in the

primitive conditions of life, but was maladaptive in advanced

societies. Because human instincts had a specific location in strands

of brain tissue, they were subject to the Lamarckian mechanism of

use - inheritance so that gradual modifications could be transmitted to

future generations. Over the course of many generations the

evolutionary process would ensure that human beings would become less

aggressive and increasingly altruistic, leading eventually to a perfect

society in which no one would cause another person pain. However,

for evolution to produce the perfect individual it was necessary for

present and future generations to experience the 'natural' consequences

of their conduct. Only in this way would individuals have the

incentives required to work on self - improvement and thus to hand an

improved moral constitution to their descendants. Hence anything that

interfered with the 'natural' relationship of conduct and consequence

was to be resisted and this included the use of the coercive power of

the state to relieve poverty, to provide public education, or to

require compulsory vaccination. Although charitable giving was to be

encouraged even it had to be limited by the consideration that

suffering was frequently the result of individuals receiving the

consequences of their actions. Hence too much individual benevolence

directed to the 'undeserving poor' would break the link between conduct

and consequence that Spencer considered fundamental to ensuring that

humanity continued to evolve to a higher level of development. Spencer adopted a utilitarian standard

of ultimate value — the greatest happiness of the greatest number — and

the

culmination of the evolutionary process would be the maximization of

utility. In the perfect society individuals would not only derive

pleasure from the exercise of altruism ('positive beneficence') but

would aim to avoid inflicting pain on others ('negative beneficence').

They would also instinctively respect the rights of others, leading to

the universal observance of the principle of justice – each person had

the right to a maximum amount of liberty that was compatible with a

like liberty in others. 'Liberty' was interpreted to mean the absence

of coercion, and was closely connected to the right to private

property. Spencer termed this code of conduct 'Absolute Ethics' which

provided a scientifically grounded moral system that could substitute

for the supernaturally based ethical systems of the past. However, he

recognized that our inherited moral constitution does not currently

permit us to behave in full compliance with the code of Absolute

Ethics, and for this reason we need a code of 'Relative Ethics' which

takes into account the distorting factors of our present imperfections. Spencer's

distinctive view of musicology was also related to his ethics. Spencer

thought that the origin of music is to be found in impassioned oratory.

Speakers have persuasive effect not only by the reasoning of their

words, but by their cadence and tone — the musical qualities of their

voice serve as "the commentary of the emotions upon the propositions of

the intellect," as Spencer put it. Music,

conceived as the heightened development of this characteristic of

speech, makes a contribution to the ethical education and progress of

the species. "The strange capacity which we have for being affected by

melody and harmony, may be taken to imply both that it is within the

possibilities of our nature to realize those intenser delights they

dimly suggest, and that they are in some way concerned in the

realization of them. If so the power and the meaning of music become

comprehensible; but otherwise they are a mystery." Spencer's

last years were characterized by a collapse of his initial optimism,

replaced instead by a pessimism regarding the future of mankind.

Nevertheless, he devoted much of his efforts in reinforcing his

arguments and preventing the misinterpretation of his monumental

theory of non - interference. Spencer's reputation among the Victorians owed a great deal to his agnosticism. He rejected theology as

representing the 'impiety of the pious.' He was to gain much notoriety

from his repudiation of traditional religion, and was frequently

condemned by religious thinkers for allegedly advocating atheism and

materialism. Nonetheless, unlike Huxley, whose agnosticism was a

militant creed directed at ‘the unpardonable sin of faith’ (in Adrian

Desmond’s phrase), Spencer insisted that he was not concerned to

undermine religion in the name of science, but to bring about a

reconciliation of the two. Starting

either from religious belief or from science, Spencer argued, we are

ultimately driven to accept certain indispensable but literally

inconceivable notions. Whether we are concerned with a Creator or the

substratum which underlies our experience of phenomena, we can frame no

conception of it. Therefore, Spencer concluded, religion and science

agree in the supreme truth that the human understanding is only capable

of 'relative' knowledge. This is the case since, owing to the inherent

limitations of the human mind, it is only possible to obtain knowledge

of phenomena, not of the reality ('the absolute') underlying phenomena.

Hence both science and religion must come to recognize as the 'most

certain of all facts that the Power which the Universe manifests to us

is utterly inscrutable.' He called this awareness of 'the Unknowable'

and he presented worship of the Unknowable as capable of being a

positive faith which could substitute for conventional religion.

Indeed, he thought that the Unknowable represented the ultimate stage

in the evolution of religion, the final elimination of its last

anthropomorphic vestiges. Spencerian

views in 21st century circulation derive from his political theories

and memorable attacks on the reform movements of the late 19th century.

He has been claimed as a precursor by libertarians and anarcho - capitalism. Economist Murray Rothbard called Social Statics "the greatest single work of libertarian political philosophy ever written." Spencer

argued that the state was not an "essential" institution and that it

would "decay" as voluntary market organization would replace the

coercive aspects of the state. He also argued that the individual had a "right to ignore the state." As a result of this perspective, Spencer was harshly critical of patriotism. In response to being told that British troops were in danger during the Second Afghan War,

he replied: "When men hire themselves out to shoot other men to order,

asking nothing about the justice of their cause, I don’t care if they

are shot themselves." Politics

in late Victorian Britain moved in directions that Spencer disliked,

and his arguments provided so much ammunition for conservatives and

individualists in Europe and America that they still are in use in the

21st century. The expression ‘There Is No Alternative’ (TINA), made famous by Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, may be traced to its emphatic use by Spencer. By

the 1880s he was denouncing "the new Toryism" (that is, the "social

reformist wing" of the Liberal party - the wing to some extent hostile

to Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone,

this faction of the Liberal party Spencer compared to the

interventionist "Toryism" of such people as the former Conservative

party Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli). In The Man versus the State (1884), he

attacked Gladstone and the Liberal party for losing its proper mission

(they should be defending personal liberty, he said) and instead

promoting paternalist social legislation (what Gladstone himself called

"Construction" an element in the modern Liberal party that he opposed).

Spencer denounced Irish land reform, compulsory education, laws to

regulate safety at work, prohibition and temperance laws, tax funded

libraries, and welfare reforms. His main objections were threefold: the

use of the coercive powers of the government, the discouragement given

to voluntary self - improvement, and the disregard of the "laws of life."

The reforms, he said, were tantamount to "socialism", which he said was

about the same as "slavery" in terms of limiting human freedom. Spencer

vehemently attacked the widespread enthusiasm for annexation of

colonies and imperial expansion, which subverted all he had predicted

about evolutionary progress from ‘militant’ to ‘industrial’ societies

and states. Spencer anticipated many of the analytical standpoints of later libertarian theorists such as Friedrich Hayek,

especially in his "law of equal liberty", his insistence on the limits

to predictive knowledge, his model of a spontaneous social order, and

his warnings about the "unintended consequences" of collectivist social

reforms.

Spencer is sometimes credited for the

Social Darwinist model

that applied the law of the survival of the fittest to society.

Humanitarian impulses had to be resisted as nothing should be allowed

to interfere with nature's laws, including the social struggle for

existence. According to a review of the JSTOR English

language database, the term "social Darwinism" was first used in an

English language academic journal in a 1895 book review by the Harvard

economist Frank Taussig (It

had been used as early as 1877 in Europe). JSTOR data indicates that

term was only used 21 times before 1931. The first time Spencer was

associated with "social Darwinism" was in a 1937 book review by Leo Rogin. Spencer's reputation as a Social Darwinist can be largely traced to Richard Hofstadter's book Social Darwinism in American Thought 1860 - 1915,

"a hostile critique of Spencer's work, published in 1944, [which] sold

in large numbers and was very influential, especially in academic

circles. It claimed that Spencer had used evolution to justify economic

and social inequality, and to support a political stance of extreme

conservatism, which led, amongst other things, to the eugenics

movement. In simple terms, it is as if Spencer's phrase, 'the survival

of the fittest,' had been claimed by him as the basis of a political

doctrine." While Hofstadter is generally credited with popularizing the term in his book "Social Darwinism in American Life" it was Talcott Parsons who

paved the way for Hofstadter. In his hugely influential book "The

Structure of Social Action" (1937) Parsons wrote that "Spencer is dead"

and then went on to define social Darwinism. "Parsons's wide definition

of Social Darwinism, including anyone who applied biological ideas in

the social sciences, also helped to admit Spencer and (to a lesser

extent) Sumner [to the category of social Darwinist]...". Use

of the term skyrocketed after Hofstader's book was published in 1944,

and Hofstader is frequently cited in the secondary literature as an

authoritative account of the Synthetic Philosophy. Princeton University economist Tim Leonard (2009) has argued, in the article Origins of the Myth of Social Darwinism, that Hofstadter's influential characterization of Spencer is flawed. According to Roderick Long,

Leonard argues that "Hofstadter is guilty of distorting Spencer's free

market views and smearing them with the taint of racist Darwinian

collectivism." Leonard

suggests that, through constant repetition, Hofstadter's Spencer has

taken on a life of its own, his views and arguments represented by the

same few passages, usually cited not directly from the source but from

Hofstadter's rather selective quotations. While Spencer did advocate

"survival of the fittest" in the competition among men, Leonard

emphasizes that it is inaccurate to call Spencer a Social Darwinist, because he actually held Lamarckian views: he believed that parents acquire traits through voluntary exertion and then pass on them to their progeny. The

claim that Spencer was a social darwinist might have its origin in a

flawed understanding of his support for competition. Whereas in biology

the competition of various organisms can result in the death of a

species or organism, the kind of competition Spencer advocated is

closer to the one used by economists, where competing individuals or

firms improve the well being of the rest of society. Furthermore,

Spencer viewed charity and altruism positively, as he believed in

voluntary association and informal care as opposed to using government

machinery.

While

most philosophers fail to achieve much of a following outside the

academy of their professional peers, by the 1870s and 1880s Spencer had

achieved an unparalleled popularity, as the sheer volume of his sales

indicate. He was probably the first, and possibly the only, philosopher

in history to sell over a million copies of his works during his own

lifetime. In the United States, where pirated editions were still

commonplace, his authorized publisher, Appleton, sold 368,755 copies

between 1860 and 1903. This figure did not differ much from his sales

in his native Britain, and once editions in the rest of the world are

added in the figure of a million copies seems like a conservative

estimate. As

William James remarked,

Spencer "enlarged the imagination, and set free the speculative mind of

countless doctors, engineers, and lawyers, of many physicists and

chemists, and of thoughtful laymen generally." The aspect of his thought that emphasized individual self - improvement found a ready audience in the skilled working class. Spencer's

influence among leaders of thought was also immense, though it was most

often expressed in terms of their reaction to, and repudiation of, his

ideas. As his American follower John Fiske observed, Spencer's ideas were to be found "running like the weft through all the warp" of Victorian thought. Such varied thinkers as Henry Sidgwick, T.H. Green, G.E. Moore, William James, Henri Bergson, and Émile Durkheim defined their ideas in relation to his. Durkheim’s Division of Labour in Society is

to a very large extent an extended debate with Spencer, from whose

sociology, many commentators now agree, Durkheim borrowed extensively. In post 1863 Uprising Poland, many of Spencer's ideas became integral to the dominant fin - de - siècle ideology, "Polish Positivism". The leading Polish writer of the period, Bolesław Prus, hailed Spencer as "the Aristotle of the nineteenth century" and adopted Spencer's metaphor of society - as - organism, giving it a striking poetic presentation in his 1884 micro-story, "Mold of the Earth", and highlighting the concept in the introduction to his most universal novel, Pharaoh (1895). The

early 20th century was hostile to Spencer. Soon after his death, his

philosophical reputation went into a sharp decline. Half a century

after his death, his work was dismissed as a "parody of philosophy", and the historian Richard Hofstadter called him "the metaphysician of the homemade intellectual, and the prophet of the cracker barrel agnostic." Nonetheless, Spencer’s thought had penetrated so deeply into the Victorian age that his influence did not disappear entirely. In the late 20th century, however, much more positive estimates have appeared. In his 1955 book, Social Darwinism in American Thought, Hofstadter commented that Spencer's views inspired Andrew Carnegie's and Willam Graham Summers' conceptions of capitalism.

Despite

his reputation as a Social Darwinist, Spencer's political thought has

been open to multiple interpretations. His political philosophy could

both provide inspiration to those who believed that individuals were

masters of their fate, who should brook no interference from a meddling

state, and those who believed that social development required a strong

central authority. In

Lochner v. New York, conservative justices of the United States Supreme Court could

find inspiration in Spencer's writings for striking down a New York law

limiting the number of hours a baker could work during the week, on the

ground that this law restricted liberty of contract. Arguing against the majority's holding that a "right to free contract" is implicit in the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. wrote:

"The Fourteenth Amendment does not enact Mr. Herbert Spencer's Social

Statics." Spencer has also been described as a quasi - anarchist, as well as an outright anarchist. Marxist theorist Georgi Plekhanov, in his 1909 book Anarchism and Socialism, labeled Spencer a "conservative Anarchist." Spencer's ideas became very influential in China and Japan largely

because he appealed to the reformers' desire to establish a strong

nation - state with which to compete with the Western powers. His

thought

was introduced by the Chinese scholar Yen Fu, who saw his writings as a prescription for the reform of the Qing state. Spencer also influenced the Japanese Westernizer Tokutomi Soho,

who believed that Japan was on the verge of transitioning from a

"militant society" to an "industrial society," and needed to quickly

jettison all things Japanese and take up Western ethics and learning. He also corresponded with Kaneko Kentaro, warning him of the dangers of imperialism. Savarkar writes in his Inside the enemy camp, about reading all of Spencer's works, of his great interest in them, of their translation into Marathi, and their influence on the likes of Tilak and Agarkar, and the affectionate sobriquet given to him in Maharashtra - Harbhat Pendse.

Spencer also exerted a great influence on

literature and rhetoric. His 1852 essay, “The Philosophy of Style,” explored a growing trend of formalist approaches to writing. Highly focused on the proper placement and ordering of the parts of an English sentence, he created a guide for effective composition. Spencer’s aim was to free prose writing from as much "friction and inertia" as possible, so that the reader would not be slowed by strenuous

deliberations concerning the proper context and meaning of a sentence.

Spencer argued that it is the writer's ideal "To so present ideas that

they may be apprehended with the least possible mental effort" by the reader. He argued that by making the meaning as readily accessible as possible, the writer would achieve the greatest possible communicative efficiency.

This was accomplished, according to Spencer, by placing all the

subordinate clauses, objects and phrases before the subject of a

sentence so that, when readers reached the subject, they had all the

information they needed to completely perceive its significance. While

the overall influence that “The Philosophy of Style” had on the field

of rhetoric was not as far reaching as his contribution to other

fields, Spencer’s voice lent authoritative support to formalist views of rhetoric. Spencer also had an influence on literature, as many novelists and short story authors came to address his ideas in their work. George Eliot, Leo Tolstoy, Thomas Hardy, Bolesław Prus, Abraham Cahan, D.H. Lawrence, Machado de Assis, Richard Austin Freeman, and Jorge Luis Borges all referenced Spencer. Arnold Bennett greatly praised First Principles, and the influence it had on Bennett may be seen in his many novels. Jack London went so far as to create a character, Martin Eden, a staunch Spencerian. It has also been suggested that the character of "Vershinin" in Anton Chekhov's play The Three Sisters is a dedicated Spencerian. H.G. Wells used Spencer's ideas as a theme in his novella, The Time Machine, employing them to explain the evolution of man into two species. It is perhaps the best testimony to the influence of

Spencer’s beliefs and writings that his reach was so diverse. He

influenced not only the administrators who shaped their societies’

inner workings, but also the artists who helped shape those societies'

ideals and beliefs.