<Back to Index>

- Economist Wassily Wassilyovich Leontief, 1905

- Writer Rusurrección María de Azkue, 1864

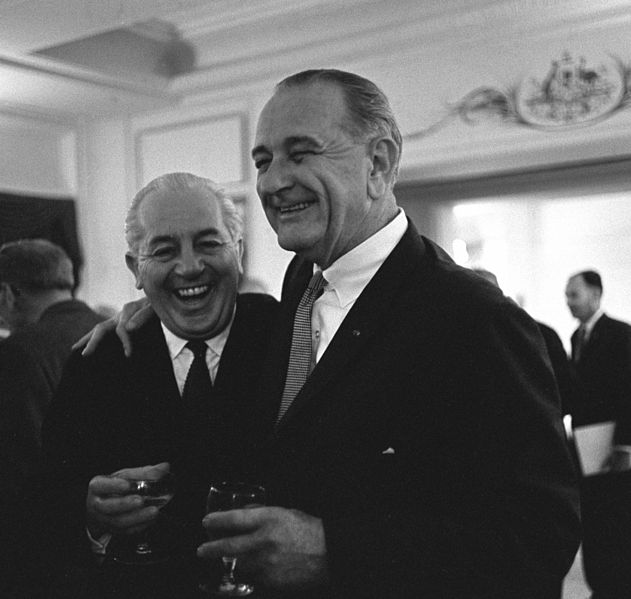

- 17th Prime Minister of Australia Harold Edward Holt, 1908

PAGE SPONSOR

Harold Edward Holt, CH, OC (5 August 1908 - ) is an Australian politician and the 17th Prime Minister of Australia.

His term as Prime Minister was brought to an early and dramatic end in December 1967 when he disappeared while swimming at Cheviot Beach near Portsea, Victoria, and was presumed drowned. Holt spent 32 years in Parliament, including many years as a senior Cabinet Minister, but was Prime Minister for only 22 months. This necessarily limited his personal and political impact, especially when compared to his immediate predecessor Sir Robert Menzies, who was Prime Minister for a total of 18 years. Today, Holt is mainly remembered for his somewhat controversial role in expanding Australia's involvement in the Vietnam War, for his famous "All the way with LBJ" quote, and for the sensational circumstances of his death. In the opinion of his biographer Tom Frame, these have tended to obscure the many achievements of Holt's long and distinguished political career.

As Minister for Immigration (1949 – 1956), Holt was responsible for the relaxation of the White Australia policy and as Treasurer under Menzies he initiated major fiscal reforms including the establishment of the Reserve Bank of Australia and launched and guided the process to convert Australia to decimal currency.

As Prime Minister, he oversaw landmark changes including the historic

decision not to devalue the Australian dollar in line with the British

pound, and the 1967 constitutional referendum in which an overwhelming majority of Australians voted in favour of giving the Commonwealth power to legislate specifically for indigenous Australians. Harold Holt was the elder of Thomas and Olive (Williams) Holt's two children. He was born in the Sydney suburb of Stanmore on 5 August 1908. He and his brother Cliff (Clifford Thomas Holt, born

1910) spent their early life in Sydney and attended three different schools in Sydney and Adelaide between 1913 and 1919. In 1921 Thomas Holt enrolled his sons at Wesley College in Melbourne, where the future Prime Minister Robert Menzies had

been a star pupil. By this time Thomas Holt had left teaching and moved

into theatrical and artist management in partnership with the noted

entrepreneur Hugh D. McIntosh, owner of the Tivoli theatre circuit. For several years in the early 1930s he was based in London. Harold

Holt's parents divorced in 1918. His mother died in 1924, when he was

sixteen, and he did not attend her funeral. A lack of parental

affection, his parents' divorce and his mother's early death instilled

deep feelings of loneliness and insecurity in the young Holt. This drove

him to seek approval and acclaim through personal endeavour and career

achievement, and fuelled his eagerness to please others and his need to

be liked. A formative event was his singing performance at his school's

annual Speech Night in December 1926 – none of his family were present,

and the sense of loneliness he felt that night remained with him throughout his life. Holt won a scholarship to Queen's College at the University of Melbourne and began his law degree in 1927. He excelled in many areas of university life – he won College 'Blues' for cricket and Australian rules football,

as well as the College Oratory and Essay Prize. He was a member of the

Melbourne Inter - University Debating team and the United Australia

Organization 'A' Grade debating team, and was president of both the

Sports and Social Club and the Law Students' Society. While at university, Holt met Zara Kate Dickins,

and they soon became lovers. However, the couple split up in 1934 and

Zara travelled overseas. In London she met Captain James Fell, a

British Army officer, and they married in March 1935. Her first son

Nicholas was born in 1937, followed by twin boys Sam and Andrew, born

in 1939. By this time, however, she had renewed her relationship with

Holt and her marriage to Fell ended soon after the twins' birth. Tom

Frame's biography reveals that Holt was the twins' biological father.

Zara and Fell subsequently divorced, she married Holt in 1946 and he

adopted the three boys. Although they remained married until Holt's

death in 1967, Zara's memoirs confirmed longstanding rumours that Holt

had a number of extramarital affairs. Holt graduated with a Bachelor of Laws in 1930. He was admitted to the Victorian Bar in November 1932 and served his articles with the Melbourne firm of Fink, Best & Miller, but the Depression meant

that he was unable to find work as a barrister. His father, based in

London at the time, wanted him to further his studies in England, but

the worsening economy also made this impossible. Holt was drawn to politics in the early 1930s and joined the Prahran branch of the United Australia Party (UAP) in 1933. At the 1934 federal election Holt unsuccessfully contested the safe Labor seat of Yarra for the UAP, running against former Prime Minister James Scullin. In March 1935, he unsuccessfully contested the safe Victorian state Labor seat of Clifton Hill. Holt stood again for the federal House of Representatives on 17 August 1935, at a by-election for the marginally conservative seat of Fawkner, this time successfully. At age 27, he was one of Australia's youngest - ever MPs. From

this point on Holt dedicated himself single - mindedly to a career in

politics and he reportedly had few outside interests, apart from his

well known passion for sport and the sea. He was a 'workaholic',

typically working up to 16 hours a day and subsisting on 4 – 5 hours sleep

each night. In 1939 Holt's mentor Robert Menzies became Prime Minister after the sudden death of the incumbent Joseph Lyons and the short - term caretaker ministry of Sir Earle Page.

Holt's energy, dedication and ability earned him rapid promotion and in

April 1939 he was appointed Minister without Portfolio assisting the

Minister for Supply and Development. In October 1939 he became Minister in charge of Scientific and Industrial Research, and during November – December 1939 he was Acting Minister for Air and Civil Aviation. In May 1940, without resigning his seat, Holt joined the Second Australian Imperial Force as a gunner, but a few months later three Cabinet ministers and several of Australia's top military staff were killed in an air crash in Canberra.

Menzies recalled Holt from the army, appointing him Minister without

Portfolio assisting the Minister for Trade and Customs, and his recall

earned him the ironic nickname "Gunner Holt." In October 1940 Holt was elevated to Cabinet, becoming Minister for Labour and National Service, and one of his most significant achievements in this portfolio was the introduction of the Child Endowment Act, passed in April 1941. In August 1941, a front - bench revolt forced Menzies to resign as Prime Minister. He was replaced by the Country Party leader Arthur Fadden.

Holt was among those who withdrew their support, although he never

revealed his reasons for doing so. In October 1941, the UAP was ousted

by a no-confidence vote, the ALP leader John Curtin was

invited to form a new government, and Menzies resigned as UAP leader.

By 1944 the UAP had effectively disintegrated and in 1945 Menzies

formally established a new political party, the Liberal Party of Australia, and forged an enduring coalition with the Country Party. Holt was one of the first members to join the Liberal Party's Prahran branch. After eight years in opposition, the Coalition won the federal election of December 1949 and

Menzies began his record - setting second term as Prime Minister. Holt at

this election after a redistribution moved seats to the new division of Higgins. Holt was appointed to the prestigious portfolios of Minister for Labour and National Service (1949 – 1958; he had previously served in this portfolio 1940 – 41) and Minister for Immigration (1949

– 1956), by which time he was being touted in the press as a "certain

successor to Menzies and a potential Prime Minister". In Immigration,

Holt continued and expanded the massive immigration program initiated

by his ALP predecessor, Arthur Calwell, and he displayed a more flexible and caring attitude than Calwell, who was a strong advocate of the White Australia policy. Holt

excelled in the Labour portfolio and has been described as one of the

best Labour ministers since Federation. Although the conditions were

ripe for industrial unrest — Communist influence in the union movement was

then at its peak, and the right - wing faction in Cabinet was openly

agitating for a showdown with the unions — the combination of strong

economic growth and Holt's enlightened approach to industrial relations

saw the number of working hours lost to strikes fall dramatically, from

over two million in 1949 to just 439,000 in 1958. Holt

fostered greater collaboration between the government, the courts,

employers and trade unions. He enjoyed good relationships with union

leaders like Albert Monk, President of the Australian Council of Trade Unions, and Jim Healy, leader of the radical Waterside Workers Federation and

he gained a reputation for tolerance, restraint and a willingness to

compromise, although his controversial decision to use troops to take

control of cargo facilities during a waterside dispute in Bowen, Queensland, in September 1953 provoked bitter criticism. Holt's

personal profile and political standing grew through the 1950s. He

served on numerous committees and overseas delegations, he was appointed

a Privy Counsellor in

1953, and in 1954 he was named one of Australia's six best - dressed

men. In 1956 he was elected Deputy Leader of the Liberal Party and

became Leader of the House, and from this point on he was generally acknowledged as Menzies' heir apparent. In December 1958, following the retirement of Arthur Fadden, Holt was appointed Treasurer.

He delivered his first Budget in August 1959 and his achievements

included major reforms to the banking system (originated by

Fadden) – including the establishment of the Reserve Bank of Australia – and the planning and preparation for the introduction of decimal currency. However,

in November 1960, Holt made one of the few major missteps of his

career. He brought down a mini - budget in an attempt to slow consumption,

control inflation and reduce the deficit, but it triggered the worst credit squeeze since

1945 — the economy was driven into recession, the stock market slumped,

private investment, housing activity and motor vehicle sales fell,

unemployment rose to almost 2 percent (the highest rate since the

Depression) and several major companies collapsed. Holt's blunder damaged his career and brought the Coalition dangerously close to losing the 1961 election, which they won with a precarious one - seat majority (the seat, Moreton, was won by Jim Killen).

Holt was roundly criticised, his public profile was damaged, and he

later described 1960 – 61 as "my most difficult year in public life". But

his political stock, like the economy, soon recovered. He

continued as federal Treasurer until January 1966, when Menzies finally

retired and Holt was elected leader, thus becoming Prime Minister. By

this time he had been an MP for almost thirty-one years — the longest wait

of any non-caretaker Australian Prime Minister. Holt was sworn in as Prime Minister on Australia Day, 26 January 1966. Holt's

term in office covered almost exactly the tumultuous calendar years of

1966 – 67. His short tenure meant that he had limited personal and

political impact as Prime Minister, and he is mainly remembered for the

dramatic circumstances of his disappearance and presumed death. This has

tended to obscure the major events and political trends of his term in

office, especially his role in maintaining and expanding Australia's military commitment to the Vietnam War. Holt's tenure fell during one of the hottest periods of the Cold War era,

and his government faced some unenviable foreign policy challenges.

Global political, commercial and military alignments were rapidly

reconfigured as the Soviets and the USA vied for world domination in

diverse theatres of conflict. Australia's ties with the UK dwindled

rapidly as Britain closed foreign bases, disengaged from its former

territories East of Suez and

began courting the EEC, as a result of which American investment in

Australia skyrocketed and Australia's onetime enemy Japan took over from

the UK as Australia's major trading partner. Strategically,

the period was dominated by Lyndon Johnson's fateful decision to

escalate the war in South East Asia. Australia's involvement in Vietnam

increased significantly under Holt, with Australian troops fighting and

dying in sometimes desperate battles like Long Tan.

Growing community unrest about the draft, the rising tide of casualties

and social debate about the moral rectitude of the war fuelled the

first significant stirrings of organised domestic opposition, such as

the influential community anti - conscription organisation Save Our Sons. There was also considerable anxiety about the volatile situation in Indonesia, in which Sukarno was replaced by General Suharto, while the Chinese Communist Party launched the cataclysmic Cultural Revolution. The precarious international situation reached a crisis point in June 1967 when the Six Day War flared in the Middle East and six days later China tested its first H-bomb. As the Space Race gathered momentum, the continuing turmoil of decolonisation visited

wars, coups, famine, armed uprisings and violent repression on

countries across South and Central America, Africa and Asia. The transfer of power from Menzies to Holt in February 1966 was smooth and unproblematic, and at the federal election later

that year the electorate overwhelmingly endorsed Holt, re-electing the

Holt - McEwen Coalition government with 56% of the two party preferred

vote. As of 2007, this still stands as the greatest winning margin at a

federal election in Australian political history. Behind

the scenes, however, Menzies' retirement had created a power vacuum in

the party, and internal divisions soon emerged. Menzies' domination of

the party, and the fact that Holt's succession had been established for

many years, meant that a secure second rank of leadership had not been

developed. Holt's disappearance at the end of 1967 forced the party to

choose a "wild card" successor from the Senate after the leading

contender, deputy Liberal leader William McMahon, was unexpectedly eliminated from the contest due to a dispute with their Coalition partners, the Country Party. Political historian James Jupp says

that, in domestic policy, Holt identified with the reformist wing of

Victorian Liberalism. One of his most notable achievements was to

initiate the process of breaking down the preferential White Australia policy by

ending the distinction between Asian and European migrants and by

permitting skilled Asians to settle with their families. He also

established the Australian Council for the Arts (later the Australia Council),

which began the tradition of federal government support for Australian

arts and artists, an initiative that was considerably expanded by Holt's

successor John Gorton. In the area of constitutional reform, undoubtedly the most significant event of Holt's time as Prime Minister was the 1967 referendum in which an overwhelming majority of Australians voted in favour of giving the Commonwealth power to legislate specifically for indigenous Australians and to include them in the Commonwealth census. In

economics, Holt's tenure began with the phasing in of Australia's new

system of decimal currency, launched on 14 February 1966, and it was

marked by a major realignment of commercial and military ties away from

the UK and towards the USA and Asia. Although all the preparatory work

for the decimal changeover had been done while Menzies was Prime

Minister, Holt had particular responsibility as Treasurer for currency

matters, and he was centrally involved in both the decision to change

and its implementation. In 1967 the Holt government made the historic decision not to depreciate the Australian dollar in line with Britain's depreciation of the pound sterling,

a custom that Australia had previously always followed, but this

decision created considerable dissent within the Coalition; Country

Party leader John McEwen was

particularly angered by the move — he saw it as a threat to Australia's

balance of payments and feared that it would lead to increased

production costs for primary industry. In

terms of party politics, one of the most significant features of Holt's

brief tenure as PM is that his unexpected death triggered the beginning

of an unprecedented period of turmoil within the Liberal Party and a

rapid decline in the Coalition's electoral fortunes. For twenty - two

years, from its founding in 1944 to his retirement in 1966, the Liberal

Party had had only one leader, Robert Menzies. After Menzies'

retirement, the party had three leaders in six years and in December

1972 the Coalition's hold on power was ended by a resounding electoral

loss to the ALP under Gough Whitlam. During Holt's term in office, the Vietnam War was

the dominant foreign policy issue. The Holt government significantly

increased Australia's military involvement in the war and Holt

vehemently defended U.S. policy in the region. Holt also forged a close relationship with U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson, whom he had first met in Melbourne in 1942. Holt

visited Washington in mid 1966 and Johnson visited Australia in October

that year, the first time a serving American president had visited Australia. Whilst

Holt stated that his friendship with Johnson was reflected in the

strong relationship between Australia and the USA, former Australian

diplomat and foreign affairs expert Alan Renouf was more cynical in his assessment of the situation. In the chapter on Vietnam in The Frightened Country,

his 1979 book on Australian foreign policy, Renouf bluntly suggested

that Holt was in effect "seduced" by Johnson, and notes that the Johnson

administration criticized the Holt government for not doing enough and

repeatedly pressured Australia to increase its troop commitment in

Vietnam. On

taking office, Holt declared that Australia had no intention of

increasing its commitment to the war, but just one month later, in

December 1966, he announced that Australia would treble its troop

commitment to 4,500, including 1,500 National Service conscripts, creating a single independent Australian task force based at Nui Dat. Five months later, in May, Holt was obliged to announce the death of the first National Service conscript in Vietnam, Private Errol Wayne Noack,

aged 21. Just before his disappearance, Holt approved a further

increase in troop numbers, committing a third battalion to the war — a

decision that was subsequently revoked by his successor, John Gorton. Holt visited the USA in late June 1966, where he gave a speech in Washington in the presence of President Johnson. Reported in The Australian on

1 July 1966, Holt's speech concluded with a remark which has come to be

seen as encapsulating his unquestioning support for Johnson, for

America's Vietnam policy and for continued Australian military

involvement in the Vietnam War: Following

his Washington visit Holt went on to London and in a speech there given

on 7 July he was sharply critical of the UK, France and other U.S.

allies that had refused to commit troops to the Vietnam War. On

20 October 1966, President Johnson arrived in Australia at Holt's

invitation for a three - day state visit, the first to Australia by a

serving U.S. President. The tour marked the first major anti - war

demonstrations staged in Australia. In Sydney, protesters lay down in

front of the car carrying Johnson and the Premier of New South Wales, Robert Askin (prompting

Askin's notorious order to "Run over the bastards"). In Melbourne, a

crowd estimated at 750,000 turned out to welcome Johnson, although a

vocal anti - war contingent demonstrated against the visit by throwing

paint bombs at Johnson's car and chanting "LBJ, LBJ, how many kids did

you kill today?". In

December, Australia signed a controversial agreement with the United

States that would allow the U.S. to establish a secret strategic communications facility at Pine Gap in the Northern Territory.

On 20 December 1966, Holt announced that Australia's military force in

Vietnam was to be increased again to 6,300 troops plus an additional

twelve tanks, two minesweepers and eight bombers. Holt

fought his first and only general election as Prime Minister on 26

November 1966, focusing his campaign on the issue of Vietnam and the

supposed Communist threat in Asia. Labor leader Arthur Calwell bitterly

opposed Australia's part in the war and promised that Australian troops

would be brought home if Labor won office, and opposition to overseas

service by Australian conscripts had long been part of ALP policy. Although

domestic opposition to the war was beginning to build, Australia's

involvement in Vietnam still enjoyed majority popular support. The

Coalition scored a stunning victory over the ALP, winning many former

ALP seats and sweeping back into power with (at the time) the largest

parliamentary majority since Federation.

The Liberal Party increased its numbers from 52 to 61, and the Country

Party from 20 to 21, with Labor dropping from 51 to 41 seats, and one

Independent. Among the new members elected was future federal Treasurer Phillip Lynch.

In early 1967, Arthur Calwell retired as ALP leader and Gough Whitlam succeeded

him. Whitlam proved a far more effective opponent, both in the media

and in parliament, and Labor soon began to recover from its losses and

gain ground, with Whitlam repeatedly besting Holt in Parliament. By

this time the long - suppressed tensions between the Coalition partners

over economic and trade policies were also beginning to emerge.

Throughout his reign as Liberal leader, Menzies had enforced strict

party discipline but, once he was gone, dissension began to surface.

Some Liberals soon became dissatisfied by what they saw as Holt's weak

leadership. Alan Reid asserts

that Holt was being increasingly criticised within the party in the

months before his death, that he was perceived as being "vague,

imprecise and evasive" and "nice to the point that his essential decency was viewed as weakness". Holt's

popularity and political standing was damaged by his perceived poor

handling of a series of controversies that emerged during 1967. In

April, the ABC's new nightly current affairs program This Day Tonight ran a story which criticised the government's decision not to reappoint the Chair of the ABC Board, Sir James Darling. Holt responded rashly, questioning the impartiality of the ABC and implying political bias on the part of journalist Mike Willesee (whose father Don Willesee was an ALP Senator and future Whitlam government minister) and his statement drew strong protests from both Willesee and the Australian Journalists' Association. In

May, increasing pressure from the media and within the Liberal Party

forced Holt to announce a parliamentary debate on the question of a second inquiry into the 1964 sinking of HMAS Voyager to be held on 16 May. The debate included the maiden speech by newly elected NSW Liberal MP Edward St John QC,

who used the opportunity to criticize the government's attitude to new

evidence about the disaster. An enraged Holt interrupted St John's

speech, in defiance of the parliamentary convention that maiden speeches

are heard in silence; his blunder embarrassed the government and

further undermined Holt's support in the Liberal Party. A few days

later, Holt announced a new Royal Commission into the disaster. In June Holt travelled to London via Canada, where on 6 June he opened the Australian Pavilion at Expo 67 in Montreal; on the return journey the Holts stayed with the Johnsons at the presidential summer resort, Camp David, in Maryland. In

October the government became embroiled in another embarrassing

controversy over the alleged misuse of VIP aircraft, which came to a

head when John Gorton (Government

Leader in the Senate) tabled documents which showed that Holt had

unintentionally misled Parliament in his earlier answers on the matter.

Support for his leadership was eroded even further by his refusal to

sack the Minister for Air Peter Howson in order to defuse the scandal, fuelling criticism from within the party that Holt was "weak" and lacked Menzies' ruthlessness. In November 1967 the government suffered a serious setback in the Senate elections, winning just 42.8 per cent of the vote against Labor's 45 per cent. The coalition also lost the seats of Corio and Dawson to

Labor in by-elections. Alan Reid says that within the party the

reversal was blamed on Holt's mishandling of the VIP planes scandal. In

December, days before Holt disappeared, the Chief Government Whip Dudley Erwin decided

to meet with Holt and confront him about growing unrest in the party.

According to Alan Reid's account, Erwin had no concerns about policy —

his anxiety was entirely focussed on Holt's leadership style, his

parliamentary performance and his public image. The

notes Erwin made for his planned meeting with Holt (which he evidently

provided to Reid) indicate that he and others were worried that Holt was

too susceptible to traps set for him by the ALP over issues like the

VIP jets scandal, and that he had repeatedly let himself become the

target of Opposition "harassment" instead of letting his ministers take

the heat on controversial issues. On

the morning of Sunday 17 December 1967, Holt, friends Christopher

Anderson, Jan Lee and George Illson and his two bodyguards drove down

from Melbourne to see the British lone yachtsman Alec Rose sail through Port Phillip Heads in his boat Lively Lady to

complete a leg of his solo circumnavigation of the globe, which started

and ended in England. Around noon, the party drove to one of Holt's

favourite swimming and snorkelling spots, Cheviot Beach on Point Nepean near Portsea, on the eastern arm of Port Phillip Bay. Holt decided to go swimming, although the surf was heavy and Cheviot Beach was notorious for its strong currents and dangerous rip tides. Ignoring

his friends pleas not to go in, Holt began swimming but soon

disappeared from view. Fearing the worst, his friends raised the alert.

Within a short time the beach and the water off shore were being

searched by a large contingent of police, Royal Australian Navy divers, Royal Australian Air Force helicopters, Army personnel from nearby Point Nepean and local volunteers. This quickly escalated into one of the largest search operations in Australian history, but no trace of Holt could be found. Two

days later, on 19 December 1967, the government made an official

announcement that Holt was presumed dead. The Governor - General Lord Casey sent for the Country Party leader and Coalition Deputy Prime Minister John McEwen, and he was sworn in as caretaker Prime Minister until such time as the Liberals elected a new leader. Holt was a strong swimmer and an experienced skindiver,

with what Holt's biographer Tom Frame describes as "incredible powers

of endurance underwater". However, his health was evidently far from

perfect at the time of his death — he had collapsed in Parliament

earlier in the year, apparently suffering from a "vitamin deficiency",

and this raised fears among some senior Liberals that he might have a

heart condition. In

September 1967 Holt had suffered a recurrence of an old shoulder

injury, which reportedly caused him agonising pain, and for this he was

prescribed strong painkillers. He ignored recent advice from his doctor Marcus de Laune Faunce not to play tennis or swim until the shoulder healed and reportedly obtained a prescription for morphine from

another doctor. Tom Frame also records that Holt had already got into

trouble twice while skindiving earlier in 1967 — on the first occasion,

while snorkeling at Portsea in May, he got into severe difficulties due

to a leaking snorkel and had to be pulled from the water by friends,

gasping for breath, blue in the face and vomiting seawater.

A memorial service held at St Paul's Anglican Cathedral in Melbourne on 22 December, was attended by a number of international dignitaries including President Johnson and Charles, Prince of Wales. Among the many Asian leaders were Nguyễn Văn Thiệu, President of South Vietnam, and Park Chung-hee, President of South Korea. It was also one of the first events to be transmitted from Australia to other countries via satellite. There

were many rumours surrounding Holt's death, including claims that he

had committed suicide or faked his own death in order to run away with

his mistress. The mystery became the subject of numerous urban myths in

Australia, including outlandish but persistent stories that he had been

kidnapped by a Chinese submarine, or that he had been abducted by a UFO.

In 1983, British journalist Anthony Grey published a controversial book

in which he claimed that Holt had been an agent for the People's

Republic of China and that he had been picked up by a Chinese submarine

off Portsea and taken to China. Many of Holt's security detail had

testified to seeing bubbles mysteriously surround him before he slipped

beneath the waves. Much of this suspicion stems from the simple fact

that his body was never found. There

have been reports from Chinese spies working for CIA, who have given a

great deal of evidence concerning Holt's alleged presence in China.

Additionally, at the time of Holt's disappearance, there was a major

on-going investigation searching for a communist spy that was known to

be operating at the highest levels of the Australian government. Holt

would have been aware of this effort and that it was a matter of time

before the traitor would be caught. Journalist Ray Martin made a documentary, Who Killed Harold Holt?, screened in November 2007, which suggested that Holt might have committed suicide. The Bulletin magazine featured a story supporting the suicide theory. In support of the view, The Bulletin quoted fellow cabinet minister Doug Anthony who spoke about Holt's depression shortly before his death. The

suggestion of suicide was rejected by Holt's son Sam, by his biographer

Tom Frame and by former prime minister and Holt's Cabinet colleague at

the time, Malcolm Fraser. On 23 October 2008 ABC Television broadcast the one - hour docudrama The Prime Minister is Missing, starring 1960s pop idol Normie Rowe as

Holt. This program covered much of the same ground as Martin's

documentary, but rejected Martin's suggestion that Holt had committed

suicide, stating that he was a vocal 'life affirmer'. The documentary

also noted that Holt was suffering a shoulder injury and had been

advised by his physician Marcus de Laune Faunce not to play tennis or swim, advice that was ignored on both counts. A different doctor had prescribed morphine for

the injured shoulder and the documentary suggested that the effect of

the drug might have impaired Holt's judgement in entering the dangerous

surf. No

official federal government enquiry was conducted, on the grounds that

it would have been a waste of time and money. Neither was an inquest

held at the time because Victorian law did not provide any mechanism for

reporting presumed or suspected deaths to the Victorian Coroner.

However, the Commonwealth and Victoria Police compiled a 108 page report

into the disappearance, including statements from all eyewitnesses and

details of the search operation. The law in Victoria was changed in 1985, and in 2003 the Victoria Police Missing

Persons Unit formally reopened 161 pre-1985 cases in which drowning was

suspected but no body was found. Holt's son Nicholas Holt said that

after 37 years there were few surviving witnesses and no new evidence

would be presented. On 2 September 2005, the Coroner's finding was that

Holt had drowned in accidental circumstances on 17 December 1967. Holt's

disappearance triggered a leadership crisis in the Liberal Party which

briefly raised the possibility of a split in the Coalition. On the

morning of 18 December Country Party leader John McEwen publicly declared that neither he nor his Country Party colleagues would serve in a Coalition if the deputy Liberal leader William McMahon were

elected as Liberal leader. McEwen refused to give his reasons, saying

only that McMahon knew what they were. In the interim, on 19 December,

McEwen was sworn in as Prime Minister on the understanding that his

commission would continue only until such time as the Liberals could

elect a new leader. With McMahon unexpectedly eliminated from the

contest, Senator John Gorton was elected Liberal leader on 9 January 1968, and was sworn in as Prime Minister on 10 January, replacing McEwen. In the Queen's Birthday Honours of June 1968, Holt's widow Zara Holt was made a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire, becoming Dame Zara Holt DBE. She later married for a third time, to a Liberal party colleague of Holt's, Jeff Bate, and was then known as Dame Zara Bate. In 1968 the newly commissioned United States Navy Knox class destroyer escort USS Harold E. Holt (FF-1074) was named in his honour. She was launched by Holt's widow Dame Zara at the Todd Shipyards in Los Angeles on 3 May 1969, and was the first American warship to bear the name of a foreign leader. In

1969 a plaque commemorating Holt was bolted to the seafloor off Cheviot

Beach after a memorial ceremony. It bears the inscription: Other memorials include: the suburb of Holt, Australian Capital Territory, the Naval Communication Station Harold E. Holt, the Division of Holt, an electoral district in the Australian House of Representatives in Victoria, a sundial and garden in the Fitzroy Gardens, Melbourne, a wing for boarders at Wesley College, Melbourne, a swimming pool in Malvern, Victoria, the

Harold Holt Fisheries Reserves – five protected areas in southern Port

Phillip, located at Swan Bay, Point Lonsdale, Mud Islands, Point Nepean and Pope’s Eye (The Annulus). Holt is most famously commemorated by the Harold Holt Memorial Swimming Centre, a swimming pool complex in the Melbourne suburb of Glen Iris.

The complex was already under construction at the time of Holt's

disappearance, and since he was Malvern's local member it was named in

his memory. The irony of commemorating him with a swimming pool has been

the source of wry amusement to some Australians. By way of a folk memorial, he is recalled in the Australian vernacular expression "do a Harold Holt" (or "do the Harry"), rhyming slang for

"do a bolt" meaning "to disappear suddenly and without explanation",

although this is usually employed in the context of disappearance from a

social gathering rather than a case of presumed death.

“ In memory of Harold Holt, Prime Minister of Australia, who loved the sea and disappeared hereabouts on 17 December 1967. ”

Bill Bryson dedicates a chapter of his book Down Under (published in the US as In a Sunburned Country) to Holt's disappearance.