<Back to Index>

- Linguist Bartol Kašić, 1575

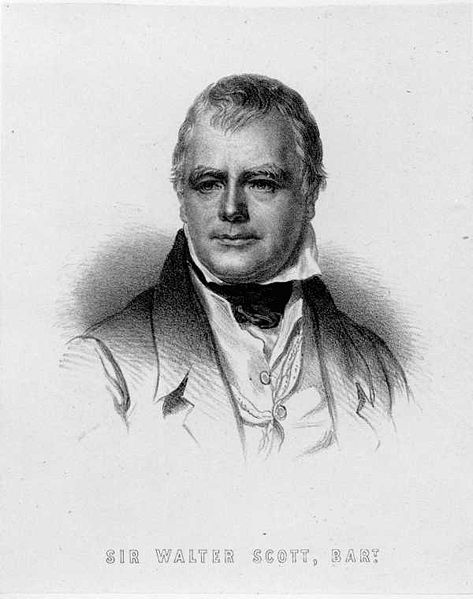

- Writer Walter Scott, 1771

- Taoiseach of Ireland John Mary "Jack" Lynch, 1917

PAGE SPONSOR

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet (15 August 1771 – 21 September 1832) was a Scottish historical novelist, playwright, and poet, popular throughout much of the world during his time.

Scott was the first English language author to have a truly international career in his lifetime, with

many contemporary readers in Europe, Australia, and North America. His

novels and poetry are still read, and many of his works remain classics

of both English language literature and of Scottish literature. Famous titles include Ivanhoe, Rob Roy, The Lady of The Lake, Waverley, The Heart of Midlothian and The Bride of Lammermoor. Scott began studying classics at the University of Edinburgh in

November 1783, at the age of only 12, a year or so younger than most of

his fellow students. In March 1786 he began an apprenticeship in his

father's office to become a Writer to the Signet. While at the university Scott had become a friend of Adam Ferguson, the son of Professor Adam Ferguson who hosted literary salons. Scott met the blind poet Thomas Blacklock who lent him books as well as introducing him to James Macpherson's Ossian cycle of poems. During the winter of 1786 – 87 the 16 year old Scott saw Robert Burns at

one of these salons, for what was to be their only meeting. When Burns

noticed a print illustrating the poem "The Justice of the Peace" and

asked who had written the poem, only Scott knew that it was by John Langhorne, and was thanked by Burns. When

it was decided that he would become a lawyer, he returned to the

university to study law, first taking classes in Moral Philosophy and

Universal History in 1789 – 90. After

completing his studies in law, he became a lawyer in Edinburgh. As a

lawyer's clerk he made his first visit to the Scottish Highlands directing an eviction. He was admitted to the Faculty of Advocates in 1792. He had an unsuccessful love suit with Williamina Belsches of Fettercairn, who married Scott´s friend Sir William Forbes, 6th Baronet. As

a boy, youth and young man, Scott was fascinated by the oral traditions

of the Scottish Borders. He was an obsessive collector of stories, and

developed an innovative method of recording what he heard at the feet of

local story tellers using carvings on twigs, to avoid the disapproval

of those who believed that such stories were neither for writing down

nor for printing. At the age of 25 he began to write professionally,

translating works from German, his first publication being rhymed versions of ballads by Gottfried August Bürger in 1796. He then published an idiosyncratic three volume set of collected ballads of his adopted home region, The Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border. This was the first sign from a literary standpoint of his interest in Scottish history. As

a result of his early polio infection, Scott had a pronounced limp.

Although a determined walker, on horseback he experienced greater

freedom of movement. Unable to consider a military career, Scott

enlisted as a volunteer in the 1st Lothian and Border yeomanry. On

a trip to the Lake District with old college friends he met Charlotte

Genevieve Charpentier (or Charpenter), daughter of Jean Charpentier of Lyon in

France, and ward of Lord Downshire in Cumberland. After three weeks of

courtship, Scott proposed and they were married on Christmas Eve 1797. They had five children, of whom only 4 survived by the time of Scott's death. In 1799 he was appointed Sheriff - Depute of the County of Selkirk, based in the Royal Burgh of Selkirk.

In his early married days Scott had a decent living from his earnings

at the law, his salary as Sheriff - Depute, his wife's income, some

revenue from his writing, and his share of his father's rather meagre

estate. In 1796, Scott's friend James Ballantyne founded

a printing press in Kelso, in the Scottish Borders. Through Ballantyne,

Scott was able to publish his first works and his poetry then began to

bring him to public attention. In 1805, The Lay of the Last Minstrel captured wide public imagination, and his career as a writer was established in

spectacular fashion. He published many other poems over the next ten

years, including the popular The Lady of the Lake, printed in 1810 and set in the Trossachs. Portions of the German translation of this work were set to music by Franz Schubert. One of these songs, Ellens dritter Gesang, is popularly labelled as "Schubert's Ave Maria". Marmion, published in 1808, produced some of his most memorable lines. Canto VI. Stanza 17 reads: Yet Clare's sharp questions must I shun In 1809, Scott persuaded James Ballantyne and

his brother to move to Edinburgh and to establish their printing press

there. He became a partner in their business. As a political

conservative and advocate of the Union with England, Scott helped to

found the Tory Quarterly Review, a review journal to which he made several anonymous contributions. In 1813 he was offered the position of Poet Laureate. He declined, and the position went to Robert Southey. Scott's

first success was his poetry. Since childhood, he had been fascinated

by stories in the oral tradition of the Scottish Borders. This drew him

to explore the writing of prose. Hitherto, the novel was accorded lower

(and often scandalous) social value compared to the epic poetry that had

brought him public acclaim. In an innovative and astute action, he

wrote and published his first novel, Waverley, under the guise of anonymity. It was a tale of the Jacobite rising of 1745 in the Kingdom of Great Britain. Its English protagonist was Edward Waverley, by his Tory upbringing sympathetic to the Jacobite cause. Becoming enmeshed in events, however, he eventually chooses Hanoverian respectability.

There followed a succession of novels over the next five years, each

with a Scottish historical setting. Mindful of his reputation as a poet,

Scott maintained the anonymity he had begun with Waverley,

always publishing the novels under the name Author of Waverley or

attributed as "Tales of..." with no author. Even when it was clear that

there would be no harm in coming out into the open, he maintained the

façade, apparently out of a sense of fun. During this time the

nickname The Wizard of the North was popularly applied to the

mysterious best selling writer. His identity as the author of the

novels was widely rumoured, and in 1815 Scott was given the honour of

dining with George, Prince Regent, who wanted to meet "the author of Waverley". In 1819 Ivanhoe,

a historical romance set in 12th century England, marked a move away

from a focus on the history and society of Scotland. Ivanhoe features a

sympathetic Jewish character named Rebecca, considered by many critics

to be the book's real heroine. This was remarkable at a time when the

struggle for the Emancipation of the Jews in England was

gathering momentum, and arguably reflects Scott's deep seated sense of

natural and humanistic justice. It too was a success, and he wrote

several others along similar lines. Scott wrote The Bride of Lammermoor based on a true story of two lovers, in the setting of the Lammermuir Hills.

In the novel, Lucie Ashton and Edgar Ravenswood exchange vows, but

Lucie's mother discovers that Edgar is an enemy of their family. She

intervenes and forces her daughter to marry Sir Arthur Bucklaw, who has

just inherited a large sum of money on the death of his aunt. On their

wedding night, Lucie stabs the bridegroom, succumbs to insanity, and

dies. Donizetti's opera Lucia di Lammermoor was based on Scott's novel. His

fame grew as his explorations and interpretations of Scottish history

and society captured popular imagination. Impressed by this, the Prince

Regent (the future George IV) gave Scott permission to search for the

fabled but long lost Honours (Crown Jewels) of Scotland, which had last

been used to crown Charles II and during the years of the Protectorate

under Cromwell had been squirrelled away. In 1818, Scott and a small

team of military men unearthed the honours from the depths of Edinburgh

Castle. A grateful Prince Regent granted Scott the title of baronet.

Later, after George's accession to the throne, the city government of

Edinburgh invited Scott, at the King's behest, to stage - manage the

King's entry into Edinburgh. With only three weeks for planning and

execution, Scott created a spectacular and comprehensive pageant,

designed not only to impress the King, but also in some way to heal the

rifts that had previously destabilised Scots society. He used the event

to contribute to the drawing of a line under an old world which pitched

his homeland into regular bouts of bloody strife. He, along with his

'production team', mounted what in modern days could be termed a PR

event, in which the (rather tubby) King was dressed in tartan, and was

greeted by his people, many of whom were also dressed in similar tartan

ceremonial dress. This form of dress, previously proscribed after the

1745 rebellion against the English, subsequently became one of the

seminal, potent and ubiquitous symbols of Scottish identity. Much

of Scott's autograph work shows an almost stream - of - consciousness

approach to writing. He included little in the way of punctuation in his

drafts, leaving such details to the printers to supply. He eventually acknowledged in 1827 that he was the author of the Waverley novels. When Scott was a boy, he sometimes travelled with his father from Selkirk to Melrose in the Border Country where

some of his novels are set. At a certain spot the old gentleman would

stop the carriage and take his son to a stone on the site of the Battle

of Melrose (1526).

Not far away was a little farm called Cartleyhole, and this Scott

eventually purchased. The farmhouse developed into a wonderful home that

has been likened to a fairy palace. Through windows enriched with the

insignia of heraldry the sun shone on suits of armour, trophies of the

chase, a library of over 9,000 volumes, fine

furniture, and still finer pictures. Panelling of oak and cedar and

carved ceilings relieved by coats of arms in their correct colours added

to the beauty of the house. It

is estimated that the building cost him over £25,000. More land

was purchased until Scott owned nearly 1,000 acres (4 km²). A

neighbouring Roman road with a ford used in olden days by the abbots of

Melrose suggested the name of Abbotsford. Although Scott died at

Abbotsford, he was buried in Dryburgh Abbey, where nearby there is a large statue of William Wallace, one of Scotland's many romanticised historical figures. From being one of the most popular novelists of the 19th century, Scott suffered from a decline in popularity after the First World War. The tone was set in E.M. Forster's classic Aspects of the Novel (1927),

where Scott was savaged as being a clumsy writer who wrote slapdash,

badly plotted novels. Scott also suffered from the rising star of Jane Austen,

who was considered merely an entertaining "woman's novelist" in the

19th century. But in the 20th century, Austen began to be seen as

perhaps the major English novelist of the first few decades of the 19th

century. As Austen's star rose, Scott's sank, although, ironically, he

had been one of the few male writers of his time to recognise Austen's

genius. Scott's

ponderousness and wordiness were out of step with Modernist

sensibilities. Nevertheless, he was responsible for two major trends

that carry on to this day. First, he essentially invented the modern

historical novel; an enormous number of imitators (and imitators of

imitators) appeared in the 19th century. It is a measure of Scott's

influence that Edinburgh's central railway station, opened in 1854 by

the North British Railway, is called Waverley. Second, his Scottish novels followed on from James Macpherson's Ossian cycle in rehabilitating the public perception of Highland culture after years in the shadows following southern distrust of hill bandits and the Jacobite rebellions. As enthusiastic chairman of the Celtic Society of Edinburgh, he contributed to the reinvention of Scottish culture. It is worth noting, however, that Scott was a Lowland Scot, and that his re-creations of the Highlands were

more than a little fanciful, in spite of his extensive travels around

his native country. This suggests that his motives in romanticising the

nobility of Highland ways of life, lie beyond any kind of simple

depiction. Scotland

was poised to move away from an era of tribal, often sectarian and

certainly socially divisive warfare, into a more contemporary diplomatic

and mercantile world. Like many politically conservative thinkers in

Scotland, Scott lived in mortal fear of a revolution in the French style

on British soil. His organisation of the visit of King George IV to Scotland in

1822 was a pivotal event intended to inspire a view of his home country

that, in his view, accentuated the 'positive' of the past whilst

allowing the age of quasi - mediaeval blood - letting to be put to rest

quietly to invent a more useful, perhaps peaceful future. After being essentially unstudied for many decades, a small revival of interest in Scott's work began in the 1970s and 1980s. Postmodern tastes

favoured discontinuous narratives and the introduction of the 'first

person', yet they were more favourable to Scott's work than Modernist

tastes. F.R. Leavis had rubbished Scott, seeing him as a thoroughly bad novelist and a thoroughly bad influence (The Great Tradition [1948]);

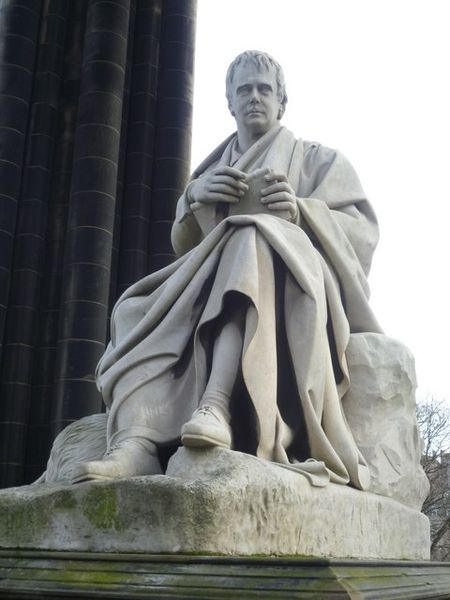

Marilyn Butler, however, offered a political reading of the fiction of

the period that found a great deal of genuine interest in his work (Romantics, Revolutionaries, and Reactionaries [1981]). Scott is now seen as an important innovator and a key figure in the development of Scottish and world literature. During his lifetime, Scott's portrait was painted by Sir Edwin Landseer and fellow Scots Sir Henry Raeburn and James Eckford Lauder. In Edinburgh, the 61.1 metre tall Victorian Gothic spire of the Scott Monument was designed by George Meikle Kemp. It was completed in 1844, 12 years after Scott's death, and dominates the south side of Princes Street. Scott is also commemorated on a stone slab in Makars' Court, outside The Writers' Museum, Lawnmarket, Edinburgh, along with other prominent Scottish writers; quotes from his work are also visible on the Canongate Wall of the Scottish Parliament building in Holyrood. There is a tower dedicated to his memory on Corstorphine Hill in the west of the city and as mentioned previous Edinburgh Waverley railway station takes the name of one of his novels. In Glasgow, Walter Scott's Monument dominates the centre of George Square, the main public square in the city. Designed by David Rhind in 1838, the monument features a large column topped by a statue of Scott. There is a statue of Scott in New York City's Central Park. The annual Walter Scott Prize for Historical Fiction was created in 2010 by the Duke and Duchess of Buccleuch,

whose ancestors were closely linked to Sir Walter Scott. At

£25,000 it is one of the largest prizes in British literature. The

award has been presented at Scott's historic home Abbotsford House.

Scott has been credited with rescuing the Scottish banknote. In 1826, there was outrage in Scotland at the attempt of Parliament to prevent the production of banknotes of less than five pounds. Scott wrote a series of letters to the Edinburgh Weekly Journal under the pseudonym "Malachi Malagrowther"

for retaining the right of Scottish banks to issue their own banknotes.

This provoked such a response that the Government was forced to relent

and allow the Scottish banks to continue printing pound notes. This

campaign is commemorated by his continued appearance on the front of all

notes issued by the Bank of Scotland. The image on the 2007 series of banknotes is based on the portrait by Henry Raeburn. In Life on the Mississippi, Mark Twain satirised

the impact of his writings, declaring that Scott "had so large a hand

in making Southern character, as it existed before the [American Civil] war", that he is in great measure responsible for the war". He

goes on to coin the term "Sir Walter Scott disease", which he blames

for the South's lack of advancement. Twain ridiculed chivalry in A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, in which the main character repeatedly utters "great Scott" as an oath. He also targeted Scott in Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, where he names a sinking boat the "Walter Scott". In To Kill a Mockingbird, the protagonist's brother is made to read Walter Scott's book Ivanhoe, and he refers to the author as "Sir Walter Scout", in reference to his own sister's nickname. In To the Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf a

few of the characters discuss their views on Scott's Waverley Novels at

dinner. Afterwards, one of the characters sits down to read and reacts

to The Antiquary. In Mother Night by Kurt Vonnegut,

Jr., memoirist and playwright Howard W. Campbell, Jr. prefaces his text

with the six lines beginning "Breathes there the man. . " In John Brown by Ralph Waldo Emerson, Emerson writes, "Walter Scott would have delighted to draw his picture and trace his adventurous career." In Knights of the Sea by Paul Marlowe, there are several quotes from and references to Marmion, as well as an inn named after Ivanhoe, and a fictitious Scott novel entitled The Beastmen of Glen Glammoch.

Born in College Wynd in the Old Town of Edinburgh in 1771, the son of a solicitor, Scott survived a childhood bout of polio in 1773 that left him lame. To cure his lameness he was sent in 1773 to live in the rural Borders region at his grandparents' farm at Sandyknowe, adjacent to the ruin of Smailholm Tower, the earlier family home. Here

he was taught to read by his aunt Jenny, and learned from her the

speech patterns and many of the tales and legends that characterised

much of his work. In January 1775 he returned to Edinburgh, and that

summer went with his aunt Jenny to take spa treatment at Bath in England, where they lived at 6 South Parade. In the winter of 1776 he went back to Sandyknowe, with another attempt at a water cure at Prestonpans during the following summer.

In 1778 Scott returned to Edinburgh for private education to prepare him for school, and in October 1779 he began at the Royal High School of Edinburgh.

He was now well able to walk and explore the city and the surrounding

countryside. His reading included chivalric romances, poems, history and

travel books. He was given private tuition by James Mitchell in

arithmetic and writing, and learned from him the history of the Kirk with emphasis on the Covenanters. After finishing school he was sent to stay for six months with his aunt Jenny in Kelso, attending the local Grammar School where he met James and John Ballantyne who later became his business partners and printed his books.

Must separate Constance from the nun

Oh! what a tangled web we weave

When first we practise to deceive!

A Palmer too! No wonder why

I felt rebuked beneath his eye

In

1825 and 1826, a banking crisis swept the City of London and Edinburgh.

The Ballantyne printing business, in which he was heavily invested,

crashed, resulting in his being very publicly ruined. Rather than

declare himself bankrupt, or to accept any kind of financial support

from his many supporters and admirers (including the King himself), he

placed his house and income in a trust belonging to his creditors, and

determined to write his way out of debt. He kept up his prodigious

output of fiction, as well as producing a biography of Napoleon Bonaparte,

until 1831. By then his health was failing. Notwithstanding this, he

undertook a grand tour of Europe, being welcomed and celebrated wherever

he went. He returned to Scotland and, in September 1832 died (under

unexplained circumstances) at Abbotsford, the home he had designed and

had built, near Melrose in the Scottish Borders. Though he died owing

money, his novels continued to sell and the debts encumbering his estate

were eventually discharged.