<Back to Index>

- Physicist Emilio Gino Segrè, 1905

- Poet Paul Fort, 1872

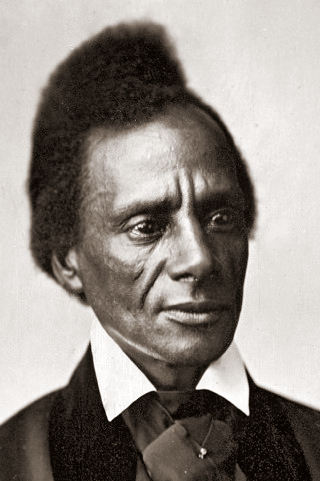

- Civil Rights Activist and 1st Woman in U.S. Senate Charles Lenox Remond and Hattie Ophelia Wyatt Caraway, 1810 and 1878

PAGE SPONSOR

Charles Lenox Remond (1 February 1810 – 22 December 1873) was an American orator, abolitionist and military organizer during the American Civil War. He was the brother of Sarah Parker Remond, also heavily engaged in the cause.

Remond was born free in Salem, Massachusetts, to John Remond, naturalised from Curaçao, a hairdresser, and Nancy Lenox, daughter of a prominent Bostonian, a hairdresser and caterer. The eldest son of eight children, He began his activism in opposition to slavery while in his twenties as orator speaking at public gatherings and conferences in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Maine, New York and Pennsylvania.

In 1838 the Massachusetts Anti - Slavery Society, chose him as one of its agents. As a delegate from the American Anti - Slavery Society, he went with William Lloyd Garrison to the World's Anti - Slavery Convention in London in 1840. The young Remond had a reputation as an eloquent lecturer and is reported to have been the first black public speaker on abolition.

In 1842 at meetings held by Remond and his sister in New Brighton, Massachusetts, Remond stated "When the world shall learn that "mind makes the man" -- that goodness; moral worth, and integrity of soul, are the true tests of Character, then prejudice against caste and color, will cease to be."

Remond recruited black soldiers in Massachusetts for the Union Army during the Civil War, particularly for the famed 54th and 55th Massachusetts Infantry. He was also active in recruiting for the U.S. Colored Troops. Remond's

family operated a hairdressing business, and catering service in which

several members participated and struck out on the own. After the war,

he worked as a clerk in the Boston Customs

House, and as a street lamp inspector. Of Remond's siblings were Nancy,

the eldest, wife of James Shearman, an oyster dealer; Caroline, a salon

owner, wife of Joseph Putnam; Cecelia, co-owner of a wig salon, wife of

James Babcock; Maritchie Juan, wig salon co-owner; Sarah Parker, abolition activist;, and John who was married to Ruth Rice. Remond

was married to Amy Matilda William Casey (her second marriage) until

her death on 15 August 1856. His second wife was Elizabeth Magee.

Remond died in Boston in 1882. Charles Remond Douglass, the son of Frederick Douglass, was named for him. Remond is buried in Harmony Grove Cemetery, in Salem. Hattie Ophelia Wyatt Caraway (February 1, 1878 – December 21, 1950) was the first woman elected to serve as a United States Senator. Senator Caraway represented Arkansas. Hattie Wyatt was born near Bakerville, Tennessee, in Humphreys County,

the daughter of William Carroll Wyatt, a farmer and shopkeeper, and

Lucy Mildred Burch. At the age of four she moved with her family to Hustburg, Tennessee. After briefly attending Ebenezer College in

Hustburg, she transferred to Dickson (Tenn.) Normal College, where she

received her B.A. degree in 1896. She taught school for a time before

marrying in 1902 Thaddeus Horatius Caraway, whom she had met in

college; they had three children, Paul Caraway, Forrest, and Robert; Paul and Forrest became Generals in the United States Army. The couple moved to Jonesboro, Arkansas, where she cared for their children and home and her husband practiced law and started a political career. The

Caraways settled in Jonesboro where he established a legal practice

while she cared for the children, tended the household and kitchen

garden, and helped to oversee the family's cotton farm. The family eventually established a second home Riversdale at Riverdale Park, Maryland. Her husband, Thaddeus Caraway, was elected to the United States House of Representatives in 1912, and he served in that office until 1921 when he was elected to the United States Senate where

he served until he died in office in 1931. Following the precedent of

appointing widows to temporarily take their husbands' places, Arkansas governor Harvey Parnell appointed

Hattie Caraway to the vacant seat, and she was sworn into office on

December 9. With the Arkansas Democratic party's backing, she easily

won a special election in January 1932 for the remaining months of the

term, becoming the first woman elected to the Senate. Although she took

an interest in her husband's political career, Hattie Caraway avoided

the capital's social and political life as well as the campaign for

women's suffrage. She recalled that "after equal suffrage I just added

voting to cooking and sewing and other household duties." In

May 1932 Caraway surprised Arkansas politicians by announcing that she

would run for a full term in the upcoming election, joining a field

already crowded with prominent candidates who had assumed she would

step aside. She told reporters, "The time has passed when a woman

should be placed in a position and kept there only while someone else

is being groomed for the job." When she was invited by Vice President Charles Curtis to preside over the Senate she took advantage of the situation to announce that she would run for reelection. Populist Louisiana politician Huey Long travelled

to Arkansas on a 9 day campaign swing to campaign for her. She was the

first female Senator to preside over this body as well as the first to

chair a Committee (Senate Committee on Enrolled Bills). Lacking

any significant political backing, Caraway accepted the offer of help

from Long, whose efforts to limit incomes and increase aid to the poor

she had supported. Long was also motivated by sympathy for the widow as

well as by his ambition to extend his influence into the home state of

his rival, Senator Joseph Robinson. Bringing his colorful and flamboyant campaign style to Arkansas, Long

stumped the state with Caraway for a week just before the Democratic

primary, helping her amass nearly twice as many votes as her closest

opponent. She went on to win the general election in November. Caraway's

Senate committee assignments included Agriculture and Forestry,

Commerce, and Enrolled Bills and Library, which she chaired. She

sustained a special interest in relief for farmers, flood control, and

veterans' benefits, all of direct concern to her constituents, and cast

her votes for nearly every New Deal measure. Her loyalty to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, however, did not extend to racial issues, and in 1938 she joined fellow southerners in a filibuster against

the administration's anti - lynching bill. Although she carefully prepared

herself for Senate work, Caraway spoke infrequently and rarely made

speeches on the floor of the Senate but built a reputation as an honest

and sincere Senator. She was sometimes portrayed by patronizing

reporters as "Silent Hattie" or "the quiet grandmother who never said

anything or did anything." She explained her reticence as unwillingness

"to take a minute away from the men. The poor dears love it so." In 1938 Caraway entered a tough fight for reelection, challenged by Representative John L. McClellan,

who argued that a man could more effectively promote the state's

interests. With backing from government employees, women's groups, and

unions, Caraway won a narrow victory in the primary and took the

general election by a large margin. During her tenure in the Senate,

three other women - Rose McConnell Long, Dixie Bibb Graves, and Gladys Pyle -

held brief tenures of two years or less in the Senate, but none of them

overlapped, and so there were never more than two women in the body.

She supported Roosevelt's foreign policy, arguing for his lend - lease bill

from her perspective as a mother with two sons in the army. While

encouraging women to contribute to the war effort, Caraway insisted

that caring for the home and family was a woman's primary task. Yet her

consciousness of women's disadvantages was evident as early as 1931,

when, upon being assigned the same Senate desk that had been briefly

occupied by the first widow ever appointed to take her husband's place,

she commented privately, "I guess they wanted as few of them

contaminated as possible." Moreover, in 1943, Caraway became the first

woman legislator to cosponsor the Equal Rights Amendment. In

her bid for reelection in 1944, Caraway placed a poor fourth in the

Democratic primary, losing her Senate seat to freshman congressman J. William Fulbright, the young, dynamic former president of the University of Arkansas who

had already gained a national reputation. Roosevelt then appointed her

to the Employees' Compensation Commission, and in 1946 President Harry Truman gave

her a post on the Employees' Compensation Appeals Board, where she

served until suffering a stroke in January 1950. She died on December

21 of the same year in Falls Church, Virginia, and was buried in West

Lawn Cemetery in Jonesboro, Arkansas. Caraway was a prohibitionist and voted against anti - lynching legislation along with many other Democratic Senators. She was generally a supporter of Franklin D. Roosevelt's

economic recovery legislation. Caraway's defiance of the Arkansas

establishment in insisting that she was more than a temporary stand in

for her husband enabled her to set a valuable precedent for women in

politics. Although she remained at the margins of power, Caraway's

diligent and capable attention to Senate responsibilities won the

respect of her colleagues, encouraged advocates of wider public roles

for women, and demonstrated that political skills were not the

exclusive property of men. She

loved her family and paid her debts; in the 1930s, one of her sons was

visiting a relative in West Tennessee, in the little town of Newbern.

The child was thrown from a horse, mortally wounded, in front of the

house of local banker Bush Crenshaw. Crenshaw had tried to save the

farmers from foreclosure during the Great Depression but his monkeying

with papers to do so had incurred a sentence to the federal

penitentiary. In gratitude for Mr. Bush's kindness to her son, Senator

Caraway intervened with President Franklin Delano Roosevelt to get a

presidential pardon for Bush Crenshaw. On February 21, 2001, the United States Postal Service issued a 76¢ Distinguished Americans series postage stamp in her honor. Her gravesite was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on September 20, 2007.