<Back to Index>

- Aviator Charles Augustus Lindbergh, 1902

- Playwright Pierre Carlet de Chamblain de Marivaux, 1688

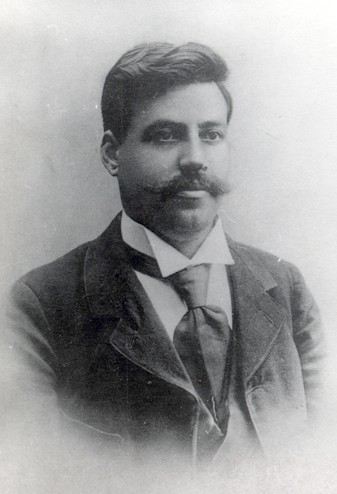

- Bulgarian Macedonian Revolutionary Georgi Nikolov (Gotse) Delchev, 1872

PAGE SPONSOR

Georgi Nikolov Delchev (1872 – 1903; Macedonian: Георги Николов Делчев, known as Gotse Delchev, also spelled Goce Delčev) was an important 19th century revolutionary figure in then Ottoman ruled Macedonia and Thrace. He was one of the leaders of what is commonly known today as Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO), a paramilitaryorganization active in the Ottoman territories in Europe at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century. At his time the name of the organization was Bulgarian Macedonian - Adrianople Revolutionary Committees (BMARC), in 1902 changed to Secret Macedonian - Adrianople Revolutionary Organization (SMARO).

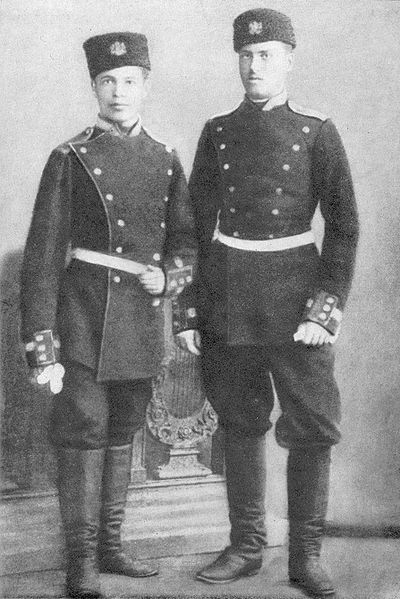

He was born in a large family on February 4, 1872 in Kilkis (Kukush), then in the Ottoman Empire (today in Greece), which was populated predominantly with Macedonians of the Orthodox faith. Since 1859 Kukush became one of the centers of the Bulgarian Uniat Church, but after 1884, most of its population gradually joined the Bulgarian Exarchate. As a student Delchev began first to study in the Bulgarian Uniate's primary school and then in the Bulgarian Exarchate's junior high school. He also read widely in the town's chitalishte, where he was impressed with revolutionary books, and especially Delchev was imbued with the ideas of Bulgarian liberation strugle. In 1888 his family sent him to the Bulgarian Men's High School of Thessaloniki, where he organized and led a secret revolutionary brotherhood. Delchev also distributed revolutionary literature, which he acquired from the school’s graduates who studied in Bulgaria. Graduation from a Bulgarian school was faced with few career prospects and Delchev decided to follow the path of his former school mate Boris Sarafov, entering the military school in Sofia in 1891. He at first encountered the newly independent Bulgaria full of idealism and dedication, but he later became disappointed with the commercialized life of the society and with the authoritarian politics of the dictator Stefan Stambolov. Gotsе spent his leaves in the company of emigrants from Macedonia. Most of them belonged to the Young Macedonian Literary Society. One of his friends was Vasil Glavinov, a leader of the Macedonian - Adrianople faction of the Bulgarian Social Democratic Workers Party. Through Glavinov and his comrades, he came into contact with a different people, who offered a new forms of social struggle. In June 1892 Delchev and the journalist Kosta Shahov, a chairman of the Young Macedonian Literary Society, met in Sofia with the bookseller from Salonica, Ivan Hadzhinikolov. Hadzhinikolov disclosed on this meeting his plans to create a revolutionary organization in Ottoman Macedonia. They discussed together its basic principles and agreed fully on all scores. Delchev explained, he has no intention of remaining an officer and promised after graduating from the Military School, he would return to Macedonia to join the organization. In 1894, only a month before graduation, he was expelled because his political activity as a member of illegal socialist circle. He was given a possibility to enter the Army again through re-applyng for commission, but he refused. Afterwards he returned to European Turkey to work there as a teacher, hoping to organize a national liberation movement through the Bulgarian Exarchate's educational net.

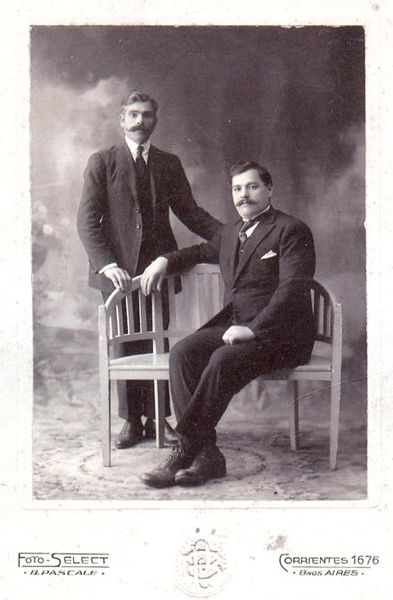

Meanwhile in Ottoman Thessaloniki a revolutionary organization was founded, by a small band of anti - Ottoman Macedono - Bulgarian revolutionaries, including Hadzhinikolov. The organization developed quickly and had managed to begin establishing a network of local organizations across Macedonia and the Adrianople Vilayet, usually centered around the schools of the Bulgarian Exarchate. The same year Delchev became a teacher in an Еxarchate's school in Štip, where he met another teacher - Dame Gruev, who was also a leader of the newly established local committee of BMARC. As a result of the close friendship between the two, Delchev joined the organization immediately, and gradually became one of its main leaders. After this, both Gruev and Delchev worked together in Štip and its environs. The expansion of the IMRO at the time was considerable, particularly after Gruev settled in Thessaloniki during the years 1895 - 1897, in the quality of a Bulgarian school inspector. Under his direction, Delchev travelled during the vacations throughout Macedonia and established and organized committees in villages and cities. Delchev also established a contacts with some of the leaders of the Supreme Macedonian - Adrianople Committee (SMAC). Its official declaration was a struggle for autonomy of Macedonia and Thrace. However, as a rule, most of SMAC's leaders were officers with stronger connections with the governments, waging terrorist struggle against the Ottomans in the hope of provoking a war and thus Bulgarian annexation of both areas. He arrived illegally in Bulgaria's capital and tried to get support from the SMAC's leadership. Delchev had a number of meetings with Danail Nikolaev, Yosif Kovachev, Toma Karayovov, Andrey Lyapchev and others, but he was often frustrated of their views. As a whole, Delchev had a negative attitude towards their activities. After spending the next school year (1895 - 1896) as a teacher in the town of Bansko, he participated in the Thessaloniki Congress of BMARC in 1896. Afterwards Delchev submitted his resignation as teacher and in 1897 he moved back to Bulgaria, where he, together with Gyorche Petrov, served as a foreign representatives of the organization in Sofia.

Delchev's involvement in BMARC was an important moment in the history of the Macedonian - Adrianople liberation movement. The years between the end of 1896, when he left the Exarchate's educational system and 1903 when he died, represented the final and most effective revolutionary phase of his short life. In this period he was a representative of the Foreign Committee of the BMARC in Sofia. Again in Sofia, negotiating with suspicious politicians and arms merchants, Delchev saw more of the unpleasant face of the Principality, and became even more disillusioned with its political system. In 1897 he, along with Gyorche Petrov, wrote the new organization's statute, which divided Macedonia and Adrianople areas into seven regions, each with a regional structure and secret police, following the Internal Revolutionary Organization's example. Below the regional committees were districts. The Central committee was placed in Salonica. In 1898 Delchev decided to be created a permanent acting armed bands (chetas) in every district. His correspondence with other BMARC / SMARO members covers extensive data on supplies, transport and storage of weapons and ammunition in Macedonia. Delchev envisioned independent production of weapons, which resulted in the establishment of a bomb manufacturing plant in the village of Sabler near Kyustendil in Bulgaria. The bombs were later smuggled across the Ottoman border into Macedonia. Gotse Delchev was the first to organize and lead a band into Macedonia with the purpose of robbing or kidnapping a rich Turks. His experiences demonstrate the weaknesses and difficulties which the Organization faced in its early years. Later he was one of the organizers of the Miss Stone Affair. He made two short visits to the Adrianople area of Thrace in 1896 and 1898. In 1900 he inspected the BMARC's detachments in Eastern Thrace again, aiming better coordination between Macedonian and Thracian revolutionary organizations. He also led the congress of the Adrianople revolutionary district held in Plovdiv in April 1902. Afterwards Delchev inspected the BMARC's structures in the Central Rhodopes. The inclusion of the rural areas into the organizational districts contributed to the expansion of the organization and the increase in its membership, while providing the essential prerequisites for the formation of the military power of the organization, at the same time having Delchev as its military advisor (inspector) and chief of all internal revolutionary bands. Delchev aimed also at better coordination between BMARC and the Supreme Macedonian - Adrianople Committee. For a short time in the late 1890s lieutenant Boris Sarafov, who was a former school mate of Delchev became its leader. At that period the foreign representatives Delchev and Petrov became by rights members of the leadership of the Supreme Committee and so BMARC even managed to gain de facto control of the SMAC. Nevertheless it soon split into two factions: one loyal to the BMARC and one led by some officers close to the Bulgarian prince. Delchev opposed this officers' insistent attempts to gain control over the activity of BMARC. Sometimes SMAC even clashed militarily with local SMARO bands as in the autumn of 1902. Then the Supreme Macedonian - Adrianople Committee organized a failed uprising in Pirin Macedonia (Gorna Dzhumaya), which merely served to provoke Ottoman repressions and hampered the work of the underground network of SMARO. The primary question regarding the timing of the uprising in Macedonia and Thrace implicated an apparent discordance not only among the SMAC and the SMARO, but also among the SMARO's leadership. At the Salonika Congress of January 1903, where Delchev did not participate, an early uprising was debated and it was decided to stage one in the Spring of 1903. This led to fierce debates among the representatives at the Sofia SMARO's Conference in March 1903. By that time two strong tendecies had crystallized within the SMARO. The right wing majority was convinced that if the Organization would unleash a general uprising, Bulgaria would be provoked to declare war of the Ottomans and after the subsequent intervention of the Great Powers the Еmpire would collapse. The left wing faction led by Delchev, on the other hand, warned against the risks of such unrealistic plans, opposing the uprising as inappropriate tactics and premature in time. Deltchev, who was under the influence of leading Bulgarian anarchists such as Mihail Gerdzhikov and Varban Kilifarski personally supported the tactics of permanent terrorist attacks as the Thessaloniki bombings of 1903. Finally, he had no choice but agree to that course of action at least managing to delay its start from May to August. Delchev also convinced the IMRO leadership to transform its idea of a mass rising involving the civil population into a rising based on guerrilla warfare. Towards the end of March 1903 Gotse with his detachment destroyed the railway bridge over Angista river, aiming to test the new guerrilla tactics. Following that in the late April he set out for Salonica to meet with Dame Gruev and to discusse the situation. After his meeting Delchev headed for Mount Ali Botush where he was expected to meet with representatives from the Seres Revolutionary District detachments. But he never made it.

Gotse Delchev died on May 4, 1903 in a skirmish with the Turkish police near the village of Banitsa, probably after betrayal by local villagers, as rumours asserted, while preparing the Ilinden - Preobrazhenie Uprising. After being identified by the local authorities in Seres, the bodies of Delchev and his comrade, Dimitar Gushtanov, were buried in a common grave in Banitsa. Soon afterwards SMARO, aided by SMAC organized the uprising against the Ottomans, which after the initial successes, was crushed with much loss of life. Two of his brothers, Mitso Delchev and Milan Delchev were also killed fighting against the Ottomans as militants in the IMRO chetas of the Bulgarian voivodas Hristo Chernopeev and Krstjo Asenov in 1901 and 1903, respectively. In 1914, with a royal decree of Tsar Ferdinand I, a pension for life was granted to their father Nikola Delchev, because of the merits of his sons to the freedom of Macedonia.

During the Second Balkan War of 1913, Kilkis, which had been annexed by Bulgaria in the First Balkan War, was taken by the Greeks. Virtually all of its pre-war 7,000 Bulgarian inhabitants, including Delchev's family, were expelled to Bulgaria by the Greek Army. The same happened to the population of Banitsa, the village where Delchev was buried. During the First World War, when Bulgaria was temporarily in control of the area, Delchev's remains were transferred to Sofia, where they rested until after the Second World War. During the Second World War, the area was taken by the Bulgarians again and Delchev's grave near Banitsa was restored. Until then Delchev was considered one of the greatest Bulgarians from Macedonia.

After 1944, the Bulgarian policy on the Macedonian Question was changed under Bulgaria's new communist regime, which was committed to the Comintern policy of supporting the development of a distinct ethnic Macedonian consciousness. Communist Yugoslavia also began to implement the same policy. Initially, Delchev was proclaimed by the Communist leader of the newly established Yugoslav People's Republic of Macedonia, Lazar Koliševski as: "...one Bulgarian of no significance for the liberation struggles...". But on October 10, 1946, under direct pressure from Moscow, as part of the policy to foster the development of separate Macedonian identity, Delchev's mortal remains were transported to Skopje. On the following day they were enshrined in a marble sarcophagus in the yard of the church "Sveti Spas", where they have remained since. After the Tito – Stalin split in 1948, Bulgaria gradually shifted to its previous view, that Macedonian Slavs are in fact Bulgarians. Yugoslav authorities, in contrast, exerted efforts to claim Delchev for the Macedonian national cause. Aiming to enforce the belief Delchev was an ethnic Macedonian, all documents written by him in standard Bulgarian were translated into the standartized in 1945 Macedonian language, and presented as originals. The new rendition of history reappraised the 1903 Ilinden Uprising as an anti - Bulgarian revolt. The past was systematycally falsified to conceal the truth, that most of the well known Macedonians had felt themselves to be Bulgarians. As a result, Delchev was declared an ethnic Macedonian hero, and Macedonian school textbooks began even to hint at Bulgarian complicity in his death. Despite the efforts of the post 1945 Yugoslav historigraphy to represent Delchev as ethnic Macedonian separatist, if he was still alive in SFRY during the late 1940s, probably he would have finished up in an internment camp, as other former IMRO activists of that time.

The international,

cosmopolitan views of Delchev could be summarized in his proverbial sentence: "I understand the world solely as a field for cultural competition among the peoples". In the late 19th century the anarchists and socialists from Bulgaria linked their struggle closely with the revolutionary movements in Macedonia and Thrace. Thus, as a young cadet in Sofia Delchev became a member of a left circle, where he was strongly influenced by the modern than Marxist and Bakunin's ideas. His views were formed also under the influence of the ideas of earlier anti - Ottoman fighters as Levski, Botev and Zahari Stoyanov, who were among the founders of the pro-Bulgrarian Internal Revolutionary Organization, the Bulgarian Revolutionary Central Committee and the Bulgarian Secret Central Revolutionary Committee, respectively. Later

he participated in the Internal organization's struggle and as well

educated leader, became one of its theoreticians and co-author of the

BMARC's statute from 1896. Developing

his ideas further in 1902 he took the step, together with other left

functionaries, of changing its nationalistic character, which

determined that members of the organization can be only Bulgarians. The

new supra - nationalistic statute renamed it to Secret Macedono - Adrianopolitan Revolutionary Organization (SMARO), which

was to be an insurgent organization, open to all Macedonians and

Thracians regardless of nationality, who wished to participate in the

movement for their autonomy. This scenario was partially facilitated by the Treaty of Berlin (1878),

according to which Macedonia and Adrianople areas were given back from

Bulgaria to the Ottomans, but especially by its unrealized 23rd.

article, which promised future autonomy for unspecified territories in European Turkey, settled with Christian population. In general, an autonomous status was

presumed to imply a special kind of constitution of the region, a

reorganization of gendarmerie, broader representation of the local

Christian population in it as well as in all the administration,

similarly to what happened in the short lived Eastern Rumelia. However, there was not a clear political agenda behind IMRO's idea about autonomy. Delcev,

like other left wing activists, vaguely determined the bonds in the

future common Macedonian - Adrianopolitan autonomous region on the one

hand, and on the other between it, the Principality of Bulgaria, and de facto annexed Eastern Rumelia. Even the possibility that Bulgaria could be absorbed into a future autonomous Macedonia, rather than the reverse, was discussed. It

is claimed that Delchev's personal view was much more likely to see

incorporation into Bulgaria as a natural final outcome of this autonomy, or eventually inclusion in a future Balkan (Con)Federative Republic after the expected dissolution of the Ottoman Empire. The last idea was probably influenced by the League for the Balkan Confederation, created in 1894 by Balkan socialists, which supported Macedonian autonomy inside a general federation of Southeast Europe. The idea of a separate Macedonian nation was as yet promoted only by small circles of intellectuals in Delchev's time, and failed to gain wide popular support. As a whole the idea of autonomy was strictly political and did not imply a secession from Bulgarian ethnicity. In

fact, for militants such as the socialist Delchev and other leftists,

that participated in the national movement retaining a political

outlook, national liberation meant "radical political liberation through shaking off the social shackles". There aren't any indications suggesting his doubt about the Bulgarian ethnic character of the Macedonians at that time. The

Bulgarian ethnic self - identification of Delchev has been recognized аs

from leading international researchers of the Macedonian Question, as well as from the Macedonian historical scholarship, although reluctantly. However, despite his Bulgarian loyalty, he was against any chauvinistic propaganda and nationalism.