<Back to Index>

- Chemist Izaak Maurits (Piet) Kolthoff, 1894

- Writer and Politician Marie Joseph Blaise de Chénier, 1764

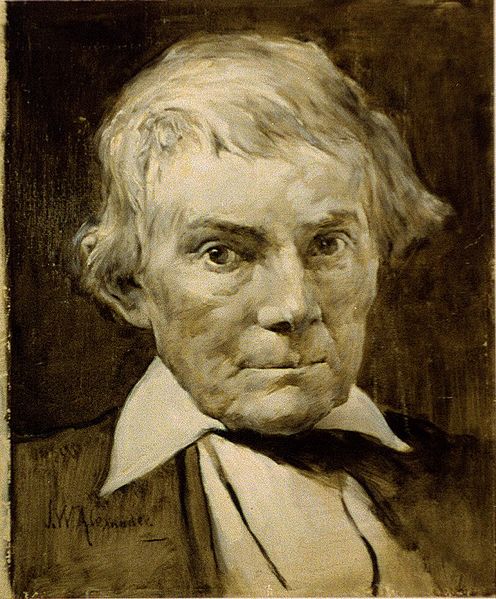

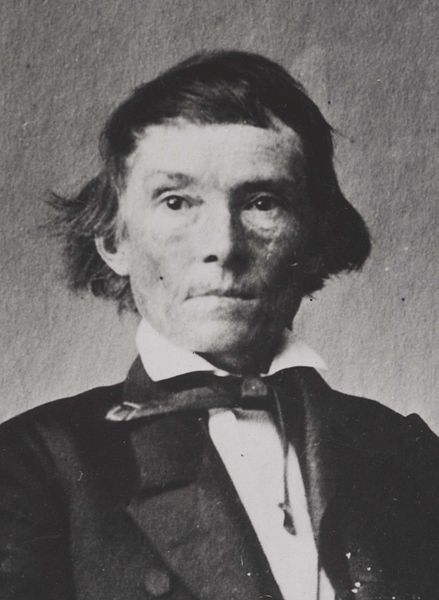

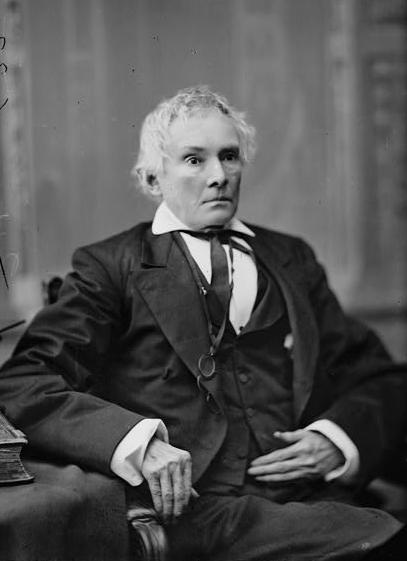

- Vice President of the Confederate States of America Alexander Hamilton Stephens, 1812

PAGE SPONSOR

Alexander Hamilton Stephens (February 11, 1812 – March 4, 1883) was an American politician from Georgia. He was Vice President of the Confederate States of America during the American Civil War. He also served as a U.S. Representative from Georgia (both before the Civil War and after Reconstruction) and as the 50th Governor of Georgia from 1882 until his death in 1883.

Stephens was born to Andrew B. and Margaret Grier Stephens on a farm near Crawfordville, Taliaferro County, Georgia. (At the time of his birth, the farm was part of Warren County and Crawfordville had not yet been founded.) He grew up poor and in difficult circumstances. His mother died when he was an infant and his father and stepmother, Matilda Stephens, died days apart when he was 14, causing him and several siblings to be scattered among relatives.

Frail but precocious, the young Stephens acquired his continued education through the generosity of several benefactors. One of them was the Presbyterian minister Alexander Hamilton Webster. Out of respect for his mentor, Stephens adopted Webster's middle name, Hamilton, as his own. Stephens attended the Franklin College (later the University of Georgia) in Athens, where he was roommates with Crawford W. Long and a member of the Phi Kappa Literary Society. He graduated at the top of his class in 1832.

After several unhappy years teaching school, he took up legal studies, passed the bar in 1834, and began a successful career as a lawyer in Crawfordville. During his 32 years of practice, he gained a reputation as a capable defender of the wrongfully accused. None of his clients charged with capital crimes were executed. One notable case was that of a slave woman accused of attempted murder. Stephens volunteered to defend her. Despite the circumstantial evidence presented against her, Stephens persuaded the jury to acquit the woman, thus saving her life.

Stephens was extremely sickly throughout his life. He often weighed less than 100 pounds, sometimes considerably less, and was frequently bedridden and near death. Descriptions of his unhealthy appearance were common in newspaper stories. While his voice was described as shrill and unpleasant, at the beginning of the Civil War a Northern newspaper described him as "the Strongest Man in the South" because of his intelligence, judgment, and eloquence. His generosity was legendary; his house, even when he was governor of Georgia, was always open to travelers or tramps, and he personally financed the education of over 100 students, black and white, male and female. So prodigious was his charity, that he died virtually penniless.

As his wealth increased,

Stephens began acquiring land and slaves. By the time of the Civil War,

Stephens owned 34 slaves and several thousand acres.

Stephens entered politics in 1836, when he was elected

to the Georgia House of Representatives. He

served there until 1841. In 1842, he was elected to

the Georgia State Senate.

In 1843, Stephens was elected U.S. Representative as a Whig, in a special election to fill the vacancy caused by the resignation of Mark A. Cooper. This seat was at - large, as Georgia did not have House districts until 1844. In 1844, 1846, and 1848, Stephens was re-elected from the 7th District as a Whig. In 1851 he was re-elected as a Unionist, in 1853 as a Whig (from the 8th District), and in 1855 and 1857 as a Democrat. He served from October 2, 1843 to March 3, 1859, from the 28th Congress through the 35th Congress.

As a national lawmaker during the crucial decades before the Civil War, Stephens was involved in all of the major sectional battles. He began as a moderate defender of slavery, but later accepted the prevailing Southern rationale used to defend the institution.

Stephens quickly rose to prominence as one of the leading Southern Whigs in the House. He supported the annexation of Texas in 1845. Along with his fellow Whigs, he vehemently opposed the Mexican - American War. He was an equally vigorous opponent of the Wilmot Proviso, which would have barred the extension of slavery into territories acquired by the United States during the war with Mexico. This would later nearly kill Stephens when he argued with Judge Reuben Cone, who stabbed him repeatedly in a fit of anger. Stephens was physically outmatched by his larger assailant, but he remained defiant during the attack, refusing to recant his positions even at the cost of his life. Only the intervention of others saved him. Stephens' wounds were serious, and he returned home to Crawfordville to recover. He and Cone reconciled before Cone's death in 1851.

Stephens and fellow Georgia Representative Robert Toombs campaigned for the election of Zachary Taylor as President in 1848. Both were chagrined and angered when Taylor proved less than pliable on aspects of the Compromise of 1850. Stephens and Toombs both supported the Compromise of 1850 though they opposed the exclusion of slavery from the territories on the theory that such lands belonged to all of the people. The pair returned to Georgia to secure support for the measures at home. Both men were instrumental in the drafting and approval of the Georgia Platform, which rallied Unionists throughout the Deep South.

Not only were Stephens and

Toombs political allies, but they were lifelong

friends. Stephens was described as "a highly sensitive

young man of serious and joyless habits of consuming

ambition, of poverty fed pride, and of morbid

preoccupation within self," a contrast to the "robust,

wealthy, and convivial Toombs. But this strange

camaraderie endured with singular accord throughout

their lives."

By this time, Stephens had departed the ranks of the Whig party — its northern wing having proved obstinate to Southern interests. Back in Georgia, Stephens, Toombs, and Democratic Representative Howell Cobb formed the Constitutional Union Party. The party overwhelmingly carried the state in the ensuing election and, for the first time, Stephens returned to Congress no longer a Whig. Stephens spent the next few years as a Constitutional Unionist, essentially an independent. He vigorously opposed the dismantling of the Constitutional Union Party when it began crumbling in 1851. Political realities soon forced the Union Democrats in the party to affiliate once more with the national party, and by mid 1852, the combination of both Democrats and Whigs, which had formed a "party" behind the Compromise, had ended.

The sectional issue surged to the forefront again in 1854, when Senator Stephen A. Douglas moved to organize the Nebraska Territory, all of which lay north of the Missouri Compromise line, in the Kansas - Nebraska Act. This legislation aroused fury in the North because it applied the popular sovereignty principle to the Territory, thereby negating the Missouri Compromise. Had it not been for Stephens, the bill would have probably never passed in the House. He employed an obscure House rule to bring the bill to a vote. He later called this "the greatest glory of my life."

From this point on, Stephens voted with the Democrats. Not until after the Congressional elections of 1855 could Stephens be properly called a Democrat, although even then he never officially declared it. In this move, Stephens broke irrevocably with many of his former Whig colleagues. When the Whig Party disintegrated after the election of 1852, some Whigs flocked to the short lived Know - Nothing Party. But Stephens fiercely opposed the Know - Nothings both for their secrecy and their anti - immigrant and anti - Catholic position.

Despite his late arrival in the Democratic Party, Stephens quickly rose through the ranks. He even served as President James Buchanan's floor manager in the House during the fruitless battle for the Lecompton Constitution for Kansas Territory in 1857. He was instrumental in framing and passing the so called English bill after it became clear that Lecompton would never pass.

Stephens did not seek re-election to Congress in 1858. As sectional peace eroded during the next two years, Stephens became increasingly critical of southern extremists. Although virtually the entire South had spurned Douglas as a traitor to Southern Rights because he had opposed the Lecompton Constitution and broken with Buchanan, Stephens remained on good terms with the Illinois Senator and served as one of his presidential electors in the election of 1860.

In 1861, Stephens was elected

as a delegate to the Georgia special convention to

decide on secession from

the United States.

During the convention, as well as during the 1860

presidential campaign, Stephens called for the

South to remain loyal to the Union, likening it to

a leaking but fixable boat. During the convention

he reminded his fellow delegates that Republicans were

a minority in Congress (especially in the Senate)

and, even with a Republican President, would be

forced to compromise just as the two sections had

for decades. And, because the Supreme Court had

voted 7–2 in the Dred Scott case,

it would take decades of Senate approved

appointments to reverse it. He voted against

secession in the convention, but asserted the

right to secede if the federal government

continued allowing northern states to nullify the Fugitive Slave Law with

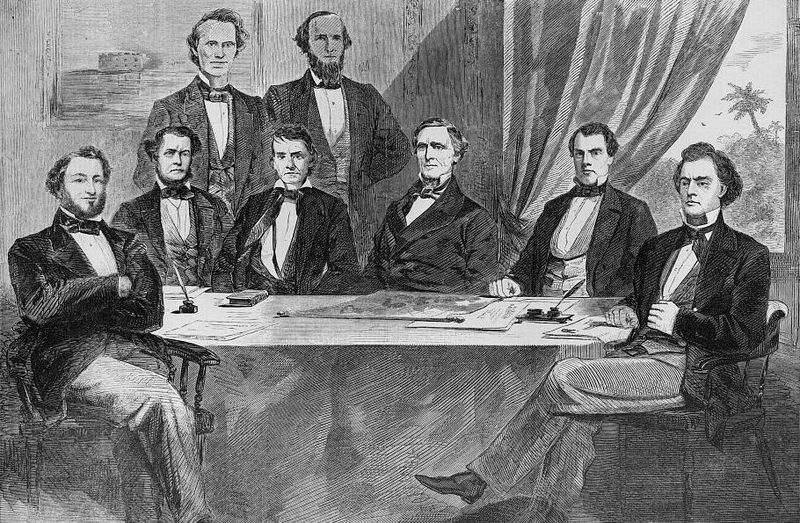

"personal liberty laws". He was elected to the Confederate Congress, and was chosen

by the Congress as Vice President of the

provisional government. He was then elected Vice

President of the Confederacy. He

took the oath of office on February 11, 1861, and

served until his arrest on May 11, 1865. Stephens

officially served in office eight days longer than

President Jefferson Davis;

he took his oath seven days before Davis'

inauguration and was captured the day after Davis.

On March 21, 1861, Stephens gave his famous Cornerstone Speech in Savannah, Georgia. In it he declared that slavery was the natural condition of blacks and the foundation of the Confederacy. He declared that, "Our new Government is founded upon exactly the opposite ideas; its foundations are laid, its cornerstone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery, subordination to the superior race, is his natural and normal condition."

On the eve of the outbreak of the Civil War, he counseled delay in moving militarily against the Northern held Fort Sumter and Fort Pickens, so that the Confederacy could build up its forces and stock resources.

In 1862, Stephens first publicly expressed his opposition to the Davis Administration. Throughout the war he denounced many of the president's policies, including conscription, suspension of the writ of habeas corpus, impressment, various financial and taxation policies, and Davis' military strategy.

In mid 1863, Davis dispatched Stephens on a fruitless mission to Washington to discuss prisoner exchanges, but in the immediate aftermath of the Federal victory of Gettysburg, the Lincoln Administration refused to receive him. As the war continued, and the fortunes of the Confederacy sank lower, Stephens became more outspoken in his opposition to the administration. On March 16, 1864, Stephens delivered a speech to the Georgia Legislature that was widely reported both North and South. In it, he excoriated the Davis Administration for its support of conscription and suspension of habeas corpus, and further, he supported a block of resolutions aimed at securing peace. From then until the end of the war, as he continued to press for actions aimed at bringing about peace, his relations with Davis, never warm to begin with, turned completely sour.

On February 3, 1865, he was one

of three Confederate commissioners who met with

Lincoln on the steamer River

Queen at

the Hampton Roads Conference, a fruitless

effort to discuss measures to bring an end to the

fight.

Stephens was arrested at his home in Crawfordville, on May 11, 1865. He was imprisoned in Fort Warren, Boston Harbor, for five months until October 1865. In 1866, he was elected to the United States Senate by the first legislature convened under the new Georgia State Constitution, but did not present his credentials, as the state had not been readmitted to the union. In 1873, he was elected U.S. Representative as a Democrat from the 8th District to fill the vacancy caused by the death of Ambrose R. Wright, and was re-elected in 1874, 1876, 1878, and 1880. He served in the 43rd through 47th Congresses, from December 1, 1873 until his resignation on November 4, 1882. On that date, he was elected and took office as Governor of Georgia. His tenure as governor proved brief; Stephens died on March 4, 1883, four months after taking office. According to a former slave, a gate fell on Stephens "and he was crippled and lamed up from dat time on 'til he died."

He was interred in Oakland Cemetery in Atlanta, then re-interred on his estate, Liberty Hall, near Crawfordville.

He is the author of A Constitutional View of the Late War Between the States (1867 – 70, 2 Vols.) and History of the United States (1871 and 1883).

He is pictured on the CSA $20.00 banknote (3rd, 5th, 6th, and 7th issues).

Stephens County, Georgia, bears his name, as

does A.H. Stephens Historic Park, a state park near

Crawfordville.