<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Stanisław Mazur, 1905

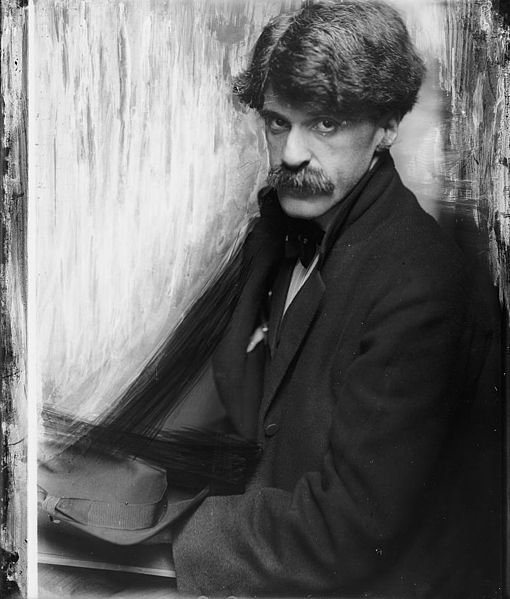

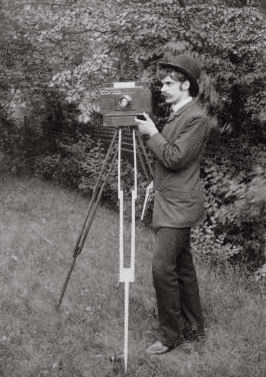

- Photographer Alfred Stieglitz, 1864

- President of the Philippines Manuel Acuña Roxas, 1892

PAGE SPONSOR

Alfred Stieglitz (January 1, 1864 – July 13, 1946) was an American photographer and modern art promoter who was instrumental over his fifty year career in making photography an accepted art form. In addition to his photography, Stieglitz is known for the New York art galleries that he ran in the early part of the 20th century, where he introduced many avant - garde European artists to the U.S. He was married to painter Georgia O'Keeffe.

Stieglitz was born in Hoboken, New Jersey, the first son of German - Jewish immigrants Edward Stieglitz (1833 – 1909) and Hedwig Ann Werner (1845 – 1922). At that time his father was a lieutenant in the Union Army, but after three years of fighting and earning an officer's salary he was able to buy an exemption from future fighting. This allowed him to stay near home during his first son's childhood, and he played an active role in seeing that he was well educated. Over the next fifteen years the Stieglitzes had five more children: Flora (1865 – 1890), twins Julius (1867 – 1937) and Leopold (1867 – 1956), Agnes (1869 – 1952) and Selma (1871 – 1957). Alfred Stieglitz was said to have been very jealous of the closeness of the twins, and as a result he spent much of his youth wishing for a soul mate of his own.

In 1871 Stieglitz was sent to the Charlier Institute, at that time the best private school in New York. He enjoyed his studies but rarely felt challenged by them. During the summers his family would leave the city and travel to Lake George in the Adirondack Mountains. As an adult Stieglitz would return frequently to this same area to rest and spend time with his family.

A year before he graduated, his parents sent him to public high school so he would qualify for admission to the City College where his uncle taught. He found the classes at the high school were far too easy to challenge him, and his father decided that the only way he would get a proper education was to enroll him in the rigorous schools of his German homeland.

In 1881 Edward Stieglitz sold his company for US$400,000 and moved his family to Europe for the next several years. Alfred Stieglitz enrolled in the Realgymnasium (high school) in Karlsruhe, while the other children studied in Weimar. Their parents, along with Hedwig Werner's sister Rosa Werner, traveled around Europe going to museums, spas and theaters. Alfred Stieglitz was reportedly entranced by the thought of his father being cared for and pampered by two different women.

The next year, Stieglitz began studying mechanical engineering at the Technische Hochschule in Berlin. He received the then enormous allowance of US$1,200 a month and spent much of his time going around the city in search of the same type of intellectual discussions he enjoyed back home. By chance he enrolled in a chemistry class taught by Hermann Wilhelm Vogel, who was an important scientist and researcher in the then developing field of photography. In Vogel, Stieglitz found both the academic challenge he needed and an outlet for his growing artistic and cultural interests. At the same time he met German artists Adolf von Menzel and Wilhelm Hasemann, both of whom introduced him to the idea of making art directly from nature. He bought his first camera and traveled through the European countryside, taking many photographs of landscapes and peasants in Germany, Italy and the Netherlands.

In 1884 his parents returned to America, but Stieglitz remained in Germany for the rest of the decade. During this time Stieglitz began to collect the first books of what would become a very large library on photography and photographers in Europe and the U.S. He read extensively as he collected, and through his library he formulated his initial thinking about photography and aesthetics. In 1887 he wrote his very first article, "A Word or Two about Amateur Photography in Germany", for the new magazine The Amateur Photographer. Soon he was regularly writing articles on the technical and aesthetic aspects of photography for magazines in England and Germany.

That same year he submitted several photographs to the annual holiday competition held by the British magazine Amateur Photographer. His photograph The Last Joke, Bellagio won first place – Stieglitz's first photographic recognition. The next year he won both first and second prizes in the same competition, and his reputation began to spread as several German and British photographic magazines began publishing his work.

In 1890 his sister Flora died during childbirth, and his parents called all of their family home to deal with the tragedy. At first Alfred Stieglitz did not want to come back to the city he now considered uncultured, but when his father threatened to cut off his allowance he reluctantly returned to New York.

By this time Stieglitz already considered himself an artist with a camera, and he refused to sell his photographs or seek employment doing anything else. His father, who was ever doting on his first - born son, helped Stieglitz by buying out a small photography business where he could indulge in his interests and perhaps earn a living on his own. Stieglitz demanded such high quality in the production and paid his employee such high wages that the business, the Photochrome Engraving Company, rarely made a profit. During that time, however, Stieglitz had made friends with the editor of The American Amateur Photographer magazine, and soon he was writing regularly for that journal. He also continued to win awards for his photographs at exhibitions, including the highly important joint exhibition of the Boston Camera Club, Photographic Society of Philadelphia and the Society of Amateur Photographers of New York.

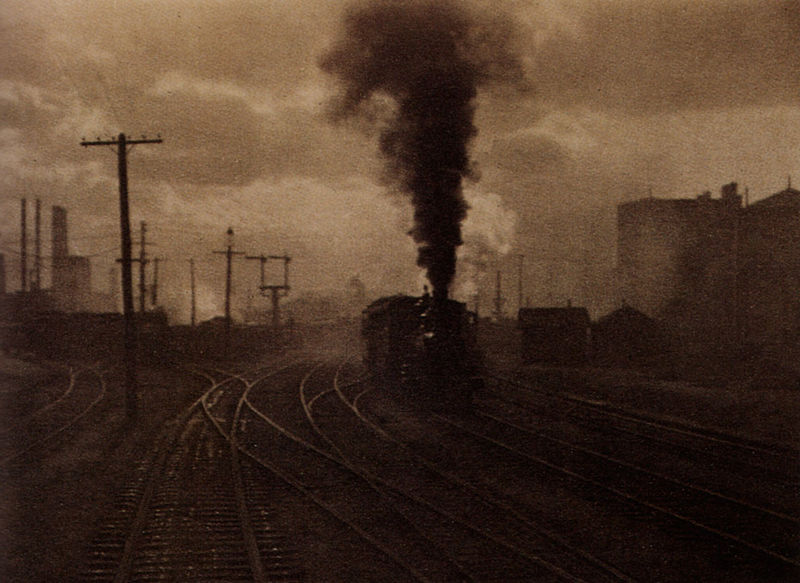

Sometime in late 1892 Stieglitz bought his first hand - held camera, a Folmer and Schwing 4x5 plate film camera. Prior to this he had been using an 8x10 plate film camera that always required a tripod and was difficult to carry around. He was invigorated by the freedom of the new camera, and later that winter he used the new camera to make two of his best known images, "Winter, Fifth Avenue" and "The Terminal".

Stieglitz soon gained a fame for both his photography and his writing about photography's place in relation to painting and other art. In the spring of 1893 he was offered the job of co-editor of The American Amateur Photographer, which he quickly accepted. In order to avoid the appearance of bias in his opinions and because Photochrome was now printing the photogravures for the magazine, Stieglitz refused to draw a salary. From then on he wrote most of the articles and reviews in the magazine, and he quickly gained an enthusiastic audience for both his technical and his critical writings.

During this period Stieglitz's parents began pressuring him to settle down and get married. For several years he had known Emmeline Obermeyer, who was the sister of his close friend and business associate Joe Obermeyer. On 16 November 1893, when she turned twenty and Stieglitz was twenty - nine, they married in New York City. Stieglitz later wrote that he did not love Emmy, as she was known, when they were first married and that their marriage was not consummated for at least a year. He indicated that their marriage was one of financial advantage for him (she had inherited money from her father, a wealthy brewery owner) at a time when his own father had lost a great deal of money in the stock market. In addition, throughout his life Stieglitz was infatuated with younger women. His mother was twelve years younger than his father, and this seemed to have had some influence on his decision to marry the much younger Emmy. He quickly regretted his brash decision to marry as he found out that Emmy could not begin to match his own artistic and cultural interests. Stieglitz biographer Richard Whelan summed up their relationship by saying Stieglitz "resented her bitterly for not becoming his twin."

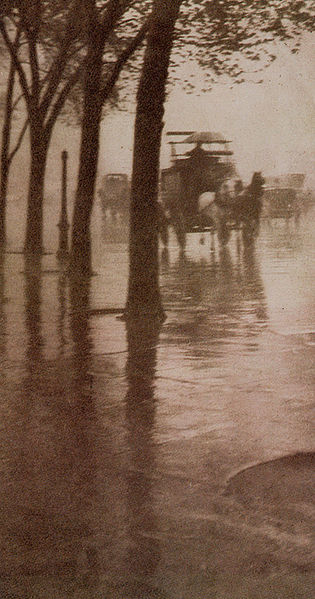

In early 1894 Stieglitz took his wife on a delayed honeymoon to Europe, and they traveled around France, Italy and Switzerland. Stieglitz photographed extensively on the trip, producing some of his early famous images such as A Venetian Canal, "The Net Mender" and A Wet Day on the Boulevard, Paris. While in Paris Stieglitz met French photographer Robert Demachy, who became a life long correspondent and colleague. He also spent some time in London where he met Linked Ring founders George Davidson and Alfred Horsley Hinton. Both would remain friends and colleagues of Stieglitz throughout much of his life.

After the couple returned to New York later in the year, Stieglitz was unanimously elected as one of the first two American members of the Linked Ring. Stieglitz saw this recognition as the impetus he needed to step up his cause of promoting artistic photography in the United States. At the time there were two photographic clubs in New York, the Society of Amateur Photographers and the New York Camera Club. Both were bound to the old technical style of photography and were moribund in their leadership and their finances. Stieglitz pushed for a merger of the two clubs, and he spent most of 1895 working to achieve this goal. He resigned from his position at the Photochrome Company and as editor of "American Amateur Photographer" in order to devote all of his time to his new mission.

In May 1896 Stieglitz succeeded, and the two organizations joined to form the Camera Club of New York. The next year he was offered the presidency of the new organization, but he took the position of vice - president instead so he could concentrate on the programs of the club rather than deal with administrative matters. Within a very short period, he was running all aspects of the organization. He told journalist Theodore Dreiser he wanted to "make the club so large, its labors so distinguished and its authority so final that [it] may satisfactorily use its great prestige to compel recognition for the individual artists without and within its walls."

To accomplish this goal Stieglitz proposed to turn the Camera Club's current newsletter into a greatly expanded magazine that would set a new standard for excellence both in the photos it published and in the writing about photography. Since no one else could match his vision and his enthusiasm, the Trustees of the Club agreed to give him full control over the new publication. In July, 1897, the first issue of Camera Notes appeared, and it soon became revered as the finest photographic magazine in the world. Over the next four years Stieglitz would use Camera Notes to champion his belief in photography as an art form by including articles on art and aesthetics next to prints by some of the leading photographers in Europe and the U.S. Later the critic Sadakichi Hartmann would write "it seemed to me that artistic photography, the Camera Club and Alfred Stieglitz were only three names for one and the same thing."

Stieglitz did not let his work at the Camera Club deter his own photography. Late in 1897 he hand - pulled the photogravures for a first portfolio of his own work, "Picturesque Bits of New York and Other Studies." He continued to exhibit in shows in Europe and the U.S., and by 1898 his reputation had reached such a point that he was asking the then staggering price of $75 for his most favorite print, "Winter – Fifth Avenue".

That same year the First Philadelphia Photographic Salon was held, and ten of Stieglitz's prints were selected. While at the Salon he met two relatively new photographers, Gertrude Käsebier and Clarence H. White, and the three soon formed close bonds.

On 27 September 1898 Stieglitz's daughter, Katherine "Kitty", was born. With assistance from Emmy's family money, the couple was able to hire a governess, cook and a chambermaid, and, believing that Emmy was well cared - for, Stieglitz saw no reason to cut back the many hours he was spending at the Camera Club and on his own photography. The couple continued to live mostly separate lives under the same roof.

In November 1898 a group of photographers in Munich, Germany, mounted an exhibit of their work in conjunction with a show of graphic prints from artists that included Edvard Munch and Henri Toulouse - Lautrec. They called themselves the "Secessionists", a term that Stieglitz latched onto for both its artistic and its social meanings. Four years later he would use this same name for a newly formed group of pictorial photographers that he organized in New York.

In May 1899 Stieglitz was given a one man exhibition at the Camera Club, consisting of eighty - seven prints. The strain of preparing for this show, coupled with the continuing efforts to produce Camera Notes, took a toll on Stieglitz's health. To lessen his burden he brought in his friends Joseph Keiley and Dallet Fugeut, neither of whom were members of the Camera Club, as associate editors of Camera Notes. Upset by this intrusion from outsiders, not to mention their own diminishing presence in the Club's publication, many of the older members of the Club began to actively campaign against Stieglitz's editorial authority. Stieglitz spent most of 1900 finding ways to outmaneuver these efforts, embroiling him in the very administrative battles that he so strongly wanted to avoid.

One of the few highlights of that year was Stieglitz's introduction to a new photographer, Edward Steichen, at the First Chicago Photographic Salon. Steichen was originally a painter, and he brought many of his painterly instincts to photography. The combination of the two art forms was perfect in Stieglitz's mind, and the two became inseparable friends and colleagues.

The challenges to Stieglitz's authority at the Camera Club continued, and by the following year he was so fraught from these confrontations that he collapsed in the first of several episodes later characterized by Stieglitz as mental breakdowns. He spent much of the summer at the family's Lake George home, Oaklawn, recuperating. When he returned to New York he announced he would resign as editor of Camera Notes. It was not his health that led to this decision, but his frustration with the old ways of thinking that still dominated the Camera Club's membership.

While Stieglitz was recuperating he had corresponded with photographer Eva Watson - Schütze, who urged him to use his influence to put together an exhibition that would be judged solely by photographers. Until that time all photographic exhibitions had been juried by painters and other types of artists, many of whom knew little about photography and its technical characteristics. Ever since the 1898 Munich exhibit Stieglitz had hoped to create a similar collective of artistically minded photographers in the U.S., and with Watson - Schütze's urging he felt the time was right to bring a group of his friends together for the purposes of creating an exhibit to be judged solely by photographers. Stieglitz began looking for a location to hold such an exhibit, and in December 1901 he was invited by Charles DeKay of the National Arts Club to put together an exhibition in which Stieglitz would have "full power to follow his own inclinations."

Within two months Stieglitz had assembled a collection of prints from a close circle of his friends, which, in homage to the Munich photographers, he called the Photo - Secession. Stieglitz had full control over the selection of prints for the show, and by putting it together Stieglitz was not only declaring a secession from the general artistic restrictions of the era but specifically from the official oversight of the Camera Club. The show opened at the Arts Club in early March 1902, and it was an immediate success. He had achieved his dream of putting together an exhibit judged solely by photographers (in this case, himself), and both the Arts Club members and the public responded with critical acclaim.

Invigorated by positive responses he received, he began formulating a plan for his next big move – to publish a completely independent magazine of pictorial photography to carry forth the same artistic standards of the Photo - Secessionist. By July he had fully resigned as editor of Camera Notes, and one month later he published a prospectus for a new journal he called Camera Work. He was determined it would be "the best and most sumptuous of photographic publications", and from the start it lived up to his ideals. The first issue was printed only four months later, in December 1902, and like all of the subsequent issues it contained beautiful hand - pulled photogravures, critical writings on photography, aesthetics and art, and reviews and commentaries on photographers and exhibitions. While there were many other magazines devoted to photography in the world, Camera Work was "the first photographic journal to be visual in focus."

Stieglitz was a perfectionist, and it showed in every aspect of Camera Work. He advanced the art of photogravure printing by demanding unprecedentedly high standards for the prints in Camera Work. The visual quality of the gravures was so high that when a set of prints failed to arrive for a Photo - Secession exhibition in Brussels, a selection of gravures from the magazine was hung instead. Most viewers assumed they were looking at the original photographs.

Throughout 1903 Stieglitz worked at a feverish pace to publish Camera Work according to his very high standards while pursuing multiple opportunities to exhibit his own work and put together shows of the Photo - Secessionists. He was, without exaggeration, "carrying out three simultaneous functions, all of them effectively", while dealing with the stresses of his home life. Although he brought on the same three associate editors he had at Camera Notes to assist with Camera Work (Dalleft Fuguet, Joseph Keiley and John Francis Strauss), he refused to let the smallest details pass without personally approving them. Later he said that he alone individually wrapped and mailed some 35,000 copies of Camera Work over the course of its publication.

By 1904 Stieglitz was once again mentally and physically exhausted. Badly needing a rest he decided to take his family to Europe in May, but in typical Stieglitz fashion he planned a grueling schedule of exhibitions, meetings and excursions. He collapsed almost upon arrival in Berlin, where he spent more than a month recuperating. He spent much of the rest of 1904 photographing Germany while his family visited their relations there. On his way back to the U. S. Stieglitz stopped in London and held a series of meetings with the leaders of the Linked Ring. He had hoped to convince them to set up a chapter of their organization in America (with Stieglitz as the director), but the membership there feared that Stieglitz would soon become their de facto leader. Before he could change their minds, he once again took ill and had to return to the U.S. without accomplishing his ambition.

He returned to more turmoil among his colleagues, with new factions competing to take on Stieglitz as the primary spokesperson for photography in America. By good fortune, while he was gone his friend Edward Steichen had returned to New York from Paris and was living in a small apartment on Fifth Avenue. He noticed that some rooms across from him were empty and thought they would be an ideal place to exhibit a small number of photographs. At first Stieglitz was not interested, but Steichen convinced him that, like Camera Work, this would be something that Stieglitz alone would control. Within a few months Stieglitz had secured the lease, assembled a collection of photographs and published an announcement about the new exhibition. On 25 November 1905 the "Little Galleries of the Photo - Secession" opened with one hundred prints by thirty-nine photographers. The gallery became an instant success, with almost fifteen thousand visitors during its first season and, more importantly, print sales that totaled nearly $2,800. Work by his friend Steichen accounted for more than half of those sales.

Stieglitz now had four "full - time" jobs at once, not including his family, and as usual he devoted himself to all but his family with seemingly boundless energy. Emmy, who had never given up thinking she would one day earn Stieglitz's love, continued giving him an allowance from her inheritance in spite of his on-going neglect. Her support allowed him to work without having to be overly concerned about financial matters, and through the combination of his jobs he became an even more relentless advocate for photography as an independent art form.

He became convinced that the only way photography would be seen as an equal to the other fine art media was for it to be exhibited and published directly next to painting, sculpture, drawings and prints. He sensed that the public had already embraced artistic photography as a legitimate art form, and that even the Photo - Secession, which he had created, was now a part of the accepted culture. In the October 1906 issue of Camera Work his friend Joseph Keiley summed up these feelings: "Today in America the real battle for which the Photo - Secession was established has been accomplished – the serious recognition of photography as an additional medium of pictorial expression." While many people would have been happy to have realized a goal as significant as this, Stieglitz, always the iconoclast, began looking for something to "rattle this growing complacency."

Two months later an artist named Pamela Coleman Smith came

into the Little Galleries and asked Stieglitz to look at some of her

drawings and watercolors. Just twenty - eight years old to Stieglitz's

forty - two, she was relatively unknown when they met. While there is

no

record of a relationship between them, Stieglitz was undoubted affected

by the combination of her youth, her exotic appearance and her unusual

art. He decided to show her work because he thought it would be "highly

instructive to compare drawings and photographs in order to judge

photography's possibilities and limitations". Her

show opened in January, 1907, and to Stieglitz's delight it attracted

far more visitors to the gallery than any of the previous photography

shows. Within a short time nearly every one of her works was sold.

Stieglitz, hoping to capitalize on the popularity of the show, took

photographs of her art work and issued a separate portfolio of his

platinum prints of her work. The

success of her show marked a turning point between the old era of

Stieglitz as revolutionary promoter of photography and new era of

Stieglitz as revolutionary promoter of modern art. In

the late spring of 1907 Stieglitz took the unusual step of

collaborating on a series of photographic experiments with his friend Clarence H. White.

Working with two models, Stieglitz and White took several dozen

photographs of their clothed and nude figures. They then printed a

small selection using a variety of somewhat unusual techniques,

including toning, waxing and drawing on platinum prints. According to

Stieglitz, the idea for their experiments came out of a discussion with

some painters about "the impossibility of the camera to do certain

things." The photographs they took together remain some of the most unusual and distinctive of his whole career. While

he was enjoying significant artistic successes, Stieglitz had no

similar fortune on the financial end of his work. Most months the

Little Galleries cost far more to operate than the meager income from

print sales, membership in the Photo - Secession was declining and even

subscriptions to Camera Work began

to drop off. The total income from all of these efforts now amounted to

less than $400 for the whole year, forcing Stieglitz – in this case,

Emmy – to make up the rest. For

years Emmy had maintained a lifestyle that was relatively extravagant

for their income level. She employed a full - time governess for Kitty,

insisting on traveling to Europe at least once a year, and stayed only

at the best hotels. In spite of her father's concerns about his growing

financial problems she insisted that the family once again travel to

Europe for the summer, and in June Stieglitz, Emmy, Kitty and their

governess once again sailed across the Atlantic. While

on his way to Europe Stieglitz took what is recognized not only as his

signature image but also as one of the most important photographs of

the 20th century. Aiming his camera at the lower class passengers in

the bow of the ship, he captured a scene he titled The Steerage. When he arrived in Paris he developed the image in a borrowed darkroom and

carried the glass plate around with him in Europe for four months. By

the time he returned to New York he was so caught up in other business

that he set it aside and did not publish or exhibit it until four years

later. While in Europe Stieglitz saw the first commercial demonstration of the Autochrome Lumière color photography process, and soon he was experimenting with it in Paris with Steichen, Frank Eugene and Alvin Langdon Coburn.

He took three of Steichen's Autochromes with him to Munich in order to

have four - color reproductions made for insertion into a future issue of Camera Work. Back

again in New York, Stieglitz had to deal with multiple problems at

once. First, he received a notice requesting his resignation from the

Camera Club. Since he had left the Club its membership had plummeted,

and it was nearly bankrupt. The Trustees blamed Stieglitz for their

problems. Stieglitz ignored their request, and after more than forty

members resigned in protest of the Trustee's actions he was reinstated

as a life member. Then, just after he presented a groundbreaking show of Auguste Rodin's

drawings, his own financial problems forced him to close the Little

Galleries for a brief period. He reopened the gallery in February 1908

under the new name "291". The

name change represented a clear break from the old way of thinking

about photography and especially about the Photo - Secession, and from

then on the gallery broke down all boundaries between traditional art

(paintings, sculptures and drawings) and photography. Stieglitz

deliberately interspersed exhibitions of what he knew would be

controversial art, such as Rodin's sexually explicit drawings, with

what Steichen called "understandable art" and with photographs. The

intention was to "set up a dialogue that would enable 291 visitors to

see, discuss and ponder the differences and similarities between

artists of all ranks and types: between painters, draftsmen, sculptors

and photographers; between European and American artists; between older

or more established figures and younger, newer practitioners." During

this same period the National Arts Club mounted a "Special Exhibition

of Contemporary Art" that included photographs by Stieglitz, Steichen,

Käsebier and White along with paintings by Mary Cassatt, William Glackens, Robert Henri, James McNeill Whistler and

others. This is thought to have been the first major show in the U.S.

in which photographers were given equal ranking with painters. For most of 1908 and 1909 Stieglitz was so wrapped up in creating shows at 291 and in publishing Camera Work that

he apparently completely neglected his own photography. If he did take

any photographs during this period he did not consider them worthy of

his standards, and none appear in the definitive catalog of his work, Alfred Stieglitz: The Key Set. In

May 1909 Stieglitz’s father Edward died, and in his will he left his

son the then significant sum of $10,000. Stieglitz was temporarily

relieved of his financial stresses, and he used this new infusion of

cash to keep his gallery and Camera Work in business for the next several years. During this period Stieglitz met Marius de Zayas,

an energetic and charismatic artist from Mexico, and soon de Zayas

became one of his closest colleagues, assisting both with shows at the

gallery and with introducing Stieglitz to new artists in Europe. As

Stieglitz’s reputation as a promoter of European modern art increased,

he soon was approached by several new American artists hoping to have

their works shown. Stieglitz was intrigued by their modern vision,

within months Alfred Maurer, John Marin and Marsden Hartley all had their works hanging on the walls of 291. In 1910, Stieglitz was invited by the director of the Albright Art Gallery to

organize a major show of the best of contemporary photography. Although

an announcement of an open competition for the show was printed in Camera Work, the fact that Stieglitz would be in charge of it generated a new round of attacks against him. An editorial in American Photography magazine

claimed that Stieglitz could no longer "perceive the value of

photographic work of artistic merit which does not conform to a

particular style which is so characteristic of all exhibitions under

his auspices. Half a generation ago this school [the Photo - Secession]

was progressive, and far in advance of its time. Today it is no

progressing, but is a reactionary force of the most dangerous type." Stieglitz

took the attacks as the equivalent of a challenge to a duel, and he was

determined to silence his critics once and for all. He wrote to fellow

photographer George Seeley "The reputation, not only of the

Photo - Secession, but of photography is at stake, and I intend to muster

all the forces available to win out for us." He

spent all summer reviewing and assembling a huge collection of entries,

and when the exhibition opened in October more than six hundred

photographs lined the walls. Critics generally praised the beautiful

aesthetic and technical qualities of the works, and overall the show

was deemed a complete success. However, his critics were mostly proven

right: the vast majority of the prints in the show were from the same

photographers Stieglitz had known for years and whose works he had

exhibited at 291. More than five hundred of the prints came from only

thirty-seven photographers, including Steichen, Coburn, Seeley, White, F. Holland Day,

and Stieglitz himself. The exhibition was a great tribute to the

Photo - Secession, but by its very size and scope it also indicated that

the Photo - Secession had become a part of the very same cultural

establishment that Stieglitz had once fought so hard against. In the January 1911 edition of Camera Work Stieglitz

took the unusual step of reprinting the entire text of a review of the

Buffalo show that included some disparaging words about White's photos.

White was outraged that his friend would provide a forum for such

criticism, and he never forgave Stieglitz. Within a year he and

Käsebier, who was also attacked in the same issue, completely

ended their friendship with Stieglitz. White soon started his own

school of photography, and Käsebier went on to co-found with White

a group called the "Pictorial Photographers of America". Throughout

1911 and early 1912 Stieglitz continued organizing ground breaking

exhibits of modern art at 291 and promoting new art along with

photography in the pages of Camera Work. By the summer of 1912 he was so enthralled with non - photographic art that he published a special number of Camera Work (August

1912) devoted solely to Matisse and Picasso. This was the first issue

of the journal that did not contain a single photograph, and it was a

clear indicator of his interests during this period. In late 1912 painters Walter Pach, Arthur B. Davies and Walt Kuhn began

organizing a great show of modern art, and Davies asked Stieglitz to

help. Stieglitz, who strongly disliked Kuhn, declined to become

involved, but he agreed to lend both a few modern art pieces from 291

to the show. He also agreed to be listed as an honorary vice - president

of the exhibition along with Claude Monet, Odilon Redon, Mabel Dodge and Isabella Stewart Gardner. In February 1913 the watershed Armory Show opened in New York, and soon modern art was a major topic of discussion

throughout the city. Stieglitz took great satisfaction in the public's

response, although much of it was not favorable, but he saw the

popularity of the show as a vindication of the work that he had been

sponsoring at 291 for the past five years. Ever

the promoter and provocateur, he quickly mounted an exhibition of his

own photographs at 291 to run while the Armory Show was in place. He

later wrote that allowing people to see both photographs and modern

paintings at the same time "afforded the best opportunity to the

student and public for a clearer understanding of the place and purpose

of the two media." The

year 1914 was extremely challenging for Stieglitz. In January his

closest friend and co-worker Joseph Keiley died. The normally stoic

Stieglitz was distraught for many weeks. The outbreak of World War I troubled

him in several ways: first, he had family and friends in Germany and

was concerned about their safety; secondly, for many years the

photogravures for Camera Work had

been printed in Germany and now he had to find another printing firm;

and finally the war caused a significant downturn in the American

economy. Suddenly art became a luxury for many people, and by the end

of the year Stieglitz was struggling to keep both 291 and Camera Work alive. He published the April issue of Camera Work in October, but it would be more than a year before he had the time and resources to publish the next issue. In

the meantime Stieglitz's friends de Zayas, Paul de Haviland, and Agnes

Meyer convinced him that the solution to his problems was to take on a

totally new project , something that would re-engage him in his

interests. Soon he began publishing a new journal, which he called 291 after

his gallery. It was a complete labor of love and intended to be the

very epitome of avant - garde culture. Like many of Stieglitz's efforts,

it was an aesthetic triumph and a financial disaster. It ceased

publication after twelve issues. During

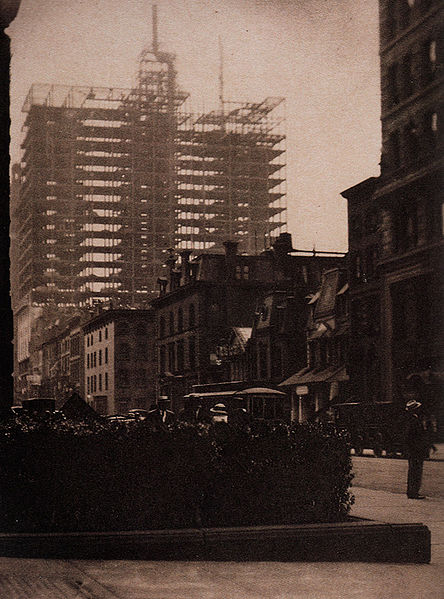

this period Stieglitz became increasingly intrigued with a more modern

visual aesthetics for photography. He had won his long battle to

achieve artistic recognition for pictorial photography, but as he

became aware of what was going on in avant - garde painting and sculpture

he found that pictorialism no longer represented the future – it was

the past. He was influenced in part by painter Charles Sheeler and by photographer Paul Strand.

In 1915, Strand, who had been coming to see shows at 291 for many

years, introduced Stieglitz to a new photographic vision was embodied

by the bold lines of everyday forms. Stieglitz was one of the first to

see the beauty and grace of Strand's style, and he gave Strand a major

exhibit at 291. He also devoted almost the entire last issue of Camera Work to his photographs. In January 1916, Stieglitz was shown a portfolio of drawings by a young artist named Georgia O'Keeffe.

Stieglitz was so taken by her art that without meeting O'Keeffe or even

getting her permission to show her works he made plans to exhibit her

work at 291. The first that O'Keeffe heard about any of this was from

another friend who saw her drawings in the gallery in late May of that

year. She finally met Stieglitz after going to 291 and chastising him

for showing her work without her permission. Stieglitz was immediately attracted to her both physically and artistically. O’Keeffe did not immediately return the interest. Soon

thereafter she met Strand, and her physical and artistic attraction

focused on him. O’Keeffe then returned to her home in Texas, and for

several months she and Strand exchanged increasingly romantic letters.

When Strand told his friend Stieglitz about his new yearning, Stieglitz

responded by telling Strand about his own infatuation with O’Keeffe.

Gradually Strand’s interest waned, and Stieglitz’s escalated. By the

summer of 1917 he and O’Keeffe were writing each other "their most

private and complicated thoughts", and it was clear that something very intense was developing.

The

year 1917 marked the end of an era in Stieglitz's life and the

beginning of another. In part because of changing aesthetics, the

changing times brought on by the war and because of his growing

relationship with O'Keeffe, he no longer had the interest or the

resources to continue what he had been doing for the past decade.

Within the period of a few months, he disbanded what was left of the

Photo - Secession, ceased publishing Camera Work and

closed the doors of 291. It was also clear to him that his marriage to

Emmy was over. He had finally found "his twin", and nothing would stand

in his way of the relationship he had wanted all of his life. During

the previous eighteen months Stieglitz and O'Keeffe had been writing to

each other with increasing passion and seeing each other whenever

possible (she was living in Texas for most of this time). In early June

O'Keeffe moved to New York after Stieglitz promised he would provide

her with a quiet studio where she could paint. They were inseparable

from the moment she arrived, and within a month he took the first of

many nude photographs of her. He chose to do this at his family's

apartment while his wife Emmy was away, but she returned while their

session was still in progress. She had suspected something was going on

between Stieglitz and O'Keeffe for a while, but his audacity in

bringing her to their home both confirmed her fears and naturally

outraged her. She told him to stop seeing her or get out. Stieglitz,

who some believe had set up the entire situation in order to provoke

the confrontation, did

not hesitate; he left and immediately found a place in the city where

he and O'Keeffe could live together. Uncertain about what this new

freedom meant for their relationship, they slept separately for more

than two weeks. By the end of July they were in the same bed together,

and by mid August when they visited Oaklawn "they were like two

teenagers in love. Several times a day they would run up the stairs to

their bedroom, so eager to make love that they would start taking their

clothes off as they ran." Stieglitz

filed for divorce almost immediately, but once he was out of their

apartment Emmy had a change of heart. Due to the legal delays caused by

Emmy and her brothers, it would be six more years before the divorce

was finalized. During this period Stieglitz and O'Keeffe continued to

live together most of the time, although she would go off on her own

from time to time. She was relatively free-spirited and out-going with

Stieglitz and his friends, but she needed solitude for weeks or months

at a time when she focused on painting or creating. This arrangement

worked well with Stieglitz's own lifestyle, and he used the times when

she was away to concentrate on his photography and on his continued

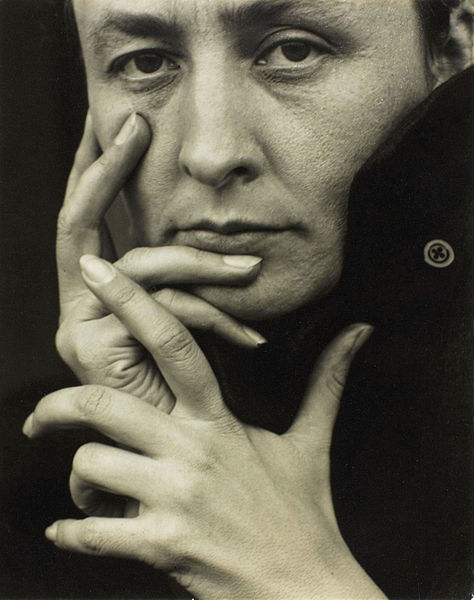

promotion of modern art. One

of the most important things that O'Keeffe provided for Stieglitz was

the muse he had always wanted. He photographed O'Keeffe obsessively

between 1918 and 1925 in what was the most prolific period in his

entire life. During this period he produced more than 350 mounted

prints of O'Keeffe that portrayed a wide range of her character, moods

and beauty. He shot many close-up studies of parts of her body,

especially her hands either isolated by themselves or near her face or

hair. The strength of these photos is that, as O'Keeffe biographer

Roxanna Robinson points out, her "personality was crucial to these

photographs; it was this, as much as her body, that Stieglitz was

recording." They remain one of the most dynamic and intimate records of a single individual in the history of art. In

1920 Stieglitz was invited by Mitchell Kennerly of the Anderson

Galleries in New York to put together a major exhibition of his

photographs. He spent much of that year mounting recent works, and in

early 1921 he hung the first one man exhibit of his photographs since

1913. Of the 146 prints he put on view, only seventeen had been seen

before. Forty - six were of O'Keeffe, including many nudes, and by

agreement with O'Keeffe she was not identified as the model on any of

the prints. It

was in the catalog for this show that Stieglitz made his famous

declaration: "I was born in Hoboken. I am an American. Photography is

my passion. The search for Truth my obsession." What is less known is

that he conditioned this statement by following it with these words: This

statement symbolized the dichotomy that Stieglitz embodied. On one hand

he was the absolute perfectionist who photographed the same scene over

and over until he was satisfied and then used only the finest papers

and printing techniques to bring in the image to completion; on the

other he completely disdained any attempt to apply artistic terminology

to his work, for it would always be that – "work" created from the

heart and not "art" created by academicians and others who had to be

"trained" to see the beauty in front of them. In 1922 Stieglitz organized a large show of John Marin's

paintings and etching at the Anderson Galleries, followed by a huge

auction of nearly two hundred paintings by more than forty American

artists, including O'Keeffe. Energized by this activity, he began one

of his most creative and unusual undertakings – photographing a series

of cloud studies simply for their form and beauty. He said: By

late summer he had created a series he called "Music – A Sequence of

Ten Cloud Photographs". Over the next twelve years he would take

hundreds of photographs of clouds without any reference points of

location or direction. These are generally recognized as the first

intentionally abstract photographs, and they remain some of his most

powerful photographs. He would come refer to these photographs as Equivalents. Stieglitz's

mother Hedwig died in November 1922, and as he did with his father he

buried his grief in his work. He spent time with Strand and his new

wife Beck, reviewed the work of another newcomer named Edward Weston and

began organizing a new show of O'Keeffe's work. Her show opened in

early 1923, and Stieglitz spent much of the spring marketing her work.

Eventually twenty of her paintings sold for more than $3,000. In the

summer O'Keeffe once again took off for the seclusion of the Southwest,

and for a while Stieglitz was alone with Beck Strand at Lake George. He

took a series of nude photos of her, and soon he became infatuated with

her. They had a brief physical affair before O'Keeffe returned in the

fall. O'Keeffe could tell what had happened, but since she did not see

Stieglitz's new lover as a serious threat to their relationship she let

things pass. Six years later she would have her own affair with Beck

Strand in New Mexico. In

1924 Stieglitz's divorce was finally approved by a judge, and within

four months he and O'Keeffe married. It was a small, private ceremony

at Marin's house, and afterward the couple went back home. There was no

reception, festivities or honeymoon. O'Keeffe said later that they

married in order to help soothe the troubles of Stieglitz's daughter

Kitty, who at that time was being treated in a sanatorium for

depression and hallucinations. The

marriage did not seem to have any immediate effect on either Stieglitz

or O'Keeffe; they both continued working on their individual projects

as they had before. For the rest of their lives together, their

relationship was, as biographer Benita Eisler characterized it, "a

collusion ... a system of deals and trade - offs, tacitly agreed to and

carried out, for the most part, without the exchange of a word.

Preferring avoidance to confrontation on most issues, O'Keeffe was the

principal agent of collusion in their union." In

the coming years O'Keeffe would spend much of her time painting in New

Mexico, while Stiegliz rarely left New York except for summers at Lake

George. O'Keeffe later said "Stieglitz was a hypochondriac and couldn't be more than 50 miles from a doctor." At the end of 1924 the Boston Museum of Fine Arts acquired

a collection of twenty - seven of Stieglitz's photographs. This was the

first time a major museum included photographs in its permanent

collection. Stieglitz donated the photos in order to have complete

control over which images would go into the collection. In

1925 Stieglitz was invited by the Anderson Galleries to put together

one of the largest exhibitions of American art that had ever been

organized, and he responded with his typical exuberance and

showmanship. The title of the show says more than any summary can offer:Alfred

Stieglitz Presents Seven Americans: 159 Paintings, Photographs, and

Things, Recent and Never Before Publicly Shown by Arthur G. Dove,

Marsden Hartley, John Marin, Charles Demuth, Paul Strand, Georgia

O'Keeffe and Alfred Stieglitz. The

show ran for three weeks and was very well attended, but when it was

over only one small painting by O'Keeffe had sold out of all the works

on exhibit. Soon

after Stieglitz was offered the continued use of one of the rooms at

the Anderson Galleries, and he decided it would be just the right space

for a series of exhibitions by some of the same artists in the Seven

Americans show. In December 1925 he opened his new gallery, publicly

called "The Intimate Gallery" but referred to by Stieglitz as "The

Room" because of its small size. Over the next four years he put

together sixteen shows of works by Marin, Dove, Hartley, O'Keeffe and

Strand, along with individual exhibits by Gaston Lachaise, Oscar Bluemner and Francis Picabia. During this time Stieglitz cultivated a relationship with influential new art collector Duncan Phillips, who purchased several works through The Intimate Gallery. In 1927 a young woman named Dorothy Norman came

to the gallery to look at works by Marin, and once again Stieglitz

became infatuated with a much younger woman. She began volunteering for

mundane tasks at the gallery, and soon she found she was returning

Stieglitz's attention. By the next year, when Stieglitz was sixty - four

and she twenty - two, they both declared their love for each other. At

this stage it was mostly an intellectual attraction – Norman was

married and had a child – but she came to the gallery almost every day

and did Stieglitz's bidding without complaints. For

most of the past year O'Keeffe had been dealing with bouts of illness

or secluded at Lake George painting, and she and Stieglitz had seen

each other only intermittently. She knew of her husband's interest in

Norman but thought it was just another of his infatuations. Having

struggled with artistic roadblocks for many months she felt she needed

a major change of some sort, so when Mabel Dodge invited

her to come to Santa Fe for the summer O'Keeffe told Stieglitz that she

had to go in order to be able to create again. Stieglitz took advantage

of her time away to begin photographing Norman, and he began teaching

her the technical aspects of printing as well. When Norman had a second

child she missed only about two months before returning to the gallery

on a regular basis. Within

a short time they became lovers, but even after their physical affair

diminished a few years later they continued to work together whenever

O'Keeffe was not around until Stieglitz died in 1946. In

early 1929 Stieglitz was told that the building that housed the Room

would be torn down later in the year. Once again he would be without a

gallery to carry out his ambitions. After a last show of Demuth's work

in May he retreated to Lake George for the summer, once again exhausted

and depressed. Without his knowledge his friends the Strands began to

raise funds for a new gallery, knowing such a project would re-energize

their old friend. In spite of terrible economy at the time they

succeeded in raising nearly sixteen thousand dollars and even found a

place that was ready to be occupied. When they surprised Stieglitz with

their gift he reacted with harsh ingratitude, saying it was time for

"young ones" to do some of the work he had been shouldering for so many

years. The

Strands were indignant, and although Stieglitz eventually apologized

and accepted their generosity the incident marked the beginning of the

end of their long and close relationship. In

the late fall Stieglitz returned to New York and set about establishing

his new domain. Not only was it the largest gallery he had ever

managed, it provided a space for his first darkroom in the city.

Previously he had borrowed other darkrooms or worked only when he was

at Lake George. On 15 December, two weeks after his sixty - fifth

birthday, Stieglitz opened his new gallery, An American Place (soon

known only as "The Place"). He continued showing group or individual

shows of his friends Marin, Demuth, Hartley, Dove and Strand for the

next sixteen years, but O'Keeffe received at least one major exhibition

each year. He fiercely controlled access to her works and incessantly

promoted her even when critics gave her less than favorable reviews.

Often during this time they would only see each other during the

summer, when it was too hot in her New Mexico home, but they wrote to

each other almost weekly with the fervor of soul mates. In

1932 Stieglitz mounted a forty - year retrospective of one hundred

twenty - seven of his works at The Place. He included all of his most

famous photographs, but he also purposely chose to include recent

photos of O'Keeffe, who, because of her years in the Southwest sun,

looked older than her forty - five years, next to portraits of his young

lover Norman. It was one of the few times he acted spitefully to

O'Keeffe in public, and it might have been as a result of their

increasingly intense arguments in private about his control over her

art. Later

that year he mounted a show of O'Keeffe's works next to some amateurish

paintings on glass by Beck Strand. He didn't bother to put together a

catalog of the show, and it was clear to the Strands that he intended

it as an insult to his ex-lover. Paul Strand never forgave Stieglitz.

He said "The day I walked into the Photo - Secession 291 [sic] in 1907

was a great moment in my life… but the day I walked out of An American

Place in 1932 was not less good. It was fresh air and personal

liberation from something that had become, for me at least,

second - rate, corrupt and meaningless." In 1936 Stieglitz returned briefly to his photographic roots by mounting one of the first exhibitions of photos by Ansel Adams in New York City. He also put on one of the first shows of Eliot Porter's work two years later. He encouraged younger photographer Todd Webb to

develop his own style and immerse himself in the medium; Stieglitz was

considered at the time to have been the "godfather of modern

photography". The next year the Cleveland Museum of Art mounted

the first major exhibition of Stieglitz's work outside of his own

galleries. He spent many hours laboring over the choices and making

sure that each print was perfect, and once again he worked himself into

exhaustion. O'Keeffe spent most of the year in New Mexico. In

early 1938, Stieglitz suffered a serious heart attack, one of six

coronary or angina attacks that would strike him over the next eight

years. Each would leave him increasingly weakened, and his recovery

times would lengthen after each one. Still, as soon as he was strong

enough he would return to The Place and pick up where he left off. In

his absence, Norman managed the gallery. Stieglitz would often sleep on

a small cot at the gallery, either too weak to leave or not wanting to

return to his usually empty home. O'Keeffe remained in her Southwest

home from spring to fall of this period. In the summer of 1946

Stieglitz suffered a fatal stroke. He remained in a coma long enough

for O'Keeffe to finally return home. When she got to his hospital room

Norman was there with him. She left immediately, and O'Keeffe was with

him when he died. According

to his wishes, a simple funeral was held with only twenty of his

closest friends and family in attendance. Stieglitz was cremated, and

O'Keeffe and his niece Elizabeth Davidson took his ashes to Lake

George. O'Keeffe never revealed exactly where she distributed them,

saying only "I put him where he could hear the water." The

day after the funeral, O'Keeffe called Norman to demand "absolute

control" over An American Place. She told Norman to clear all of her

things out of the gallery, and ended by saying that she considered

Norman's relationship with Stieglitz to be "absolutely disgusting." O'Keeffe

then began the monumental task of assembling all of Stieglitz's estate.

He had more than 3,000 photographs of his own, 850 works of art mostly

by artists he represented, 580 prints by other photographers, an

enormous collection of books and writings, plus nearly 50,000 pieces of

correspondence. She was given the sole authority over his belongings,

and took three years to personally sort through every piece. She gave

most of his works to major museums in the U.S., including the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC, with other collections at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Museum of Modern Art, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Art Institute of Chicago, Boston Museum of Fine Arts, Library of Congress and Fisk University. His correspondence went to the Beinecke Rare Books Room and Manuscript Library at Yale University.

During

the course of his long career, Stieglitz produced more than 2,500

mounted photographs. After his death O’Keeffe committed to assembling

the best and most complete set of his photographs, selecting in most

cases what she considered to be only the finest print of each image he

made. In some cases she included slightly different versions of the

same image, and these series are invaluable for their insights about

Stieglitz's aesthetic composition. She chose only those prints that

Stieglitz had personally mounted, since he did not consider a work to

be finished until he completed this step. In 1949 she donated the first

part of what she called the "key set" of 1,317 Stieglitz photographs to

the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC.

In 1980 she added to the set another 325 photographs taken by Stieglitz

of her, including many nudes. Now numbering 1,642 photographs, it is

the largest, most complete collection of Stieglitz's work anywhere in

the world. In 2002 the National Gallery published a two volume,

1,012 page catalog that reproduced the complete key set along with

detailed annotations about each photograph.

Some of his quotations: