<Back to Index>

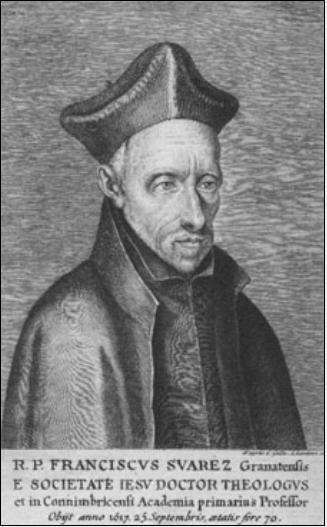

- Philosopher Francisco Suárez, 1548

- Poet André Henri Constant van Hasselt, 1806

- Commodore of the U.S. Navy Stephen Decatur, Jr., 1779

PAGE SPONSOR

Francisco Suárez (5 January 1548 – 25 September 1617) was a Spanish Jesuit priest, philosopher and theologian, one of the leading figures of the School of Salamanca movement, and generally regarded among the greatest scholastics after Thomas Aquinas.

Francisco Suárez was born at Granada, in southern Spain. At the age of sixteen Suarez entered the Society of Jesus at Salamanca, and he studied philosophy and theology there for five years from 1565 to 1570. It appears that he was not a promising student at first; indeed, he nearly gave up his thoughts of study after twice failing the entrance exam. After passing the exam at the third attempt, however, things changed, and he completed his course of study in philosophy with distinction, going on to study theology, then to teach philosophy at Ávila and Segovia. He was ordained in 1572, and taught theology at Ávila and Segovia (1575), Valladolid (1576), Rome (1580 – 85), Alcalá (1585 – 92), Salamanca (1592 – 97), and Coimbra (1597 – 1616).

He wrote on a wide variety of subjects, producing a vast amount of work (his complete works in Latin amount to twenty - six volumes). Suárez's writings include treatises on law, the relationship between church and state, metaphysics, and theology. He is considered the father of international law and his Disputationes metaphysicae were widely read in Europe during the seventeenth century and is considered by some scholars to be his most profound work.

Suárez was regarded during his lifetime as being the greatest living philosopher and theologian, and given the nickname Doctor Eximius et Pius; Pope Gregory XIII attended his first lecture in Rome. Pope Paul V invited him to refute the errors of James I of England, and wished to retain him near his person, to profit by his knowledge. Philip II of Spain sent him to the University of Coimbra in order to give it prestige, and when Suárez visited the University of Barcelona, the doctors of the university went out to meet him wearing the insignia of their faculties.

After his death in Portugal (in either Lisbon or Coimbra) his reputation grew still greater, and he had a direct influence on such leading philosophers as Hugo Grotius, René Descartes, John Norris, and Gottfried Leibniz.

In 1679 Pope Innocent XI publicly condemned sixty - five casuist propositions, taken chiefly from the writings of Escobar, Suárez and others, mostly Jesuit, theologians as propositiones laxorum moralistarum and forbade anyone to teach them under penalty of excommunication.

His

most important philosophical achievements were in metaphysics and the

philosophy of law. Suárez may be considered almost the last

eminent representative of

scholasticism. He adhered to a moderate form of Thomism and developed metaphysics as a systematic enquiry.

For Suárez, metaphysics was the science of real essences (and existence); it was mostly concerned with real being rather than conceptual being, and with immaterial rather than with material being. He held (along with earlier scholastics) that essence and existence are the same in the case of God (ontological argument), but disagreed with Aquinas and others that the essence and existence of finite beings are really distinct. He argued that in fact they are merely conceptually distinct: rather than being really separable, they can only logically be conceived as separate.

On the vexed subject of universals, he endeavored to steer a middle course between the realism of Duns Scotus and the nominalism of William of Occam. His position is a little bit closer to nominalism than that of Thomas Aquinas. Sometimes he is classified as amoderate nominalist, but his admitting of objective precision (praecisio obiectiva) ranks him with moderate realists. The only veritable and real unity in the world of existences is the individual; to assert that the universal exists separately ex parte rei would be to reduce individuals to mere accidents of one indivisible form. Suárez maintains that, though the humanity of Socrates does not differ from that of Plato, yet they do not constitute realiter one and the same humanity; there are as many "formal unities" (in this case, humanities) as there are individuals, and these individuals do not constitute a factual, but only an essential or ideal unity ("ita ut plura individua, quae dicuntur esse ejusdem naturae, non sint unum quid vera entitate quae sit in rebus, sed solum fundamentaliter vel per intellectum"). The formal unity, however, is not an arbitrary creation of the mind, but exists "in natura rei ante omnem operationem intellectus."

His metaphysical work, giving a remarkable effort of systematisation, is a real history of medieval thought, combining the three schools available at that time: Thomism, Scotism and Nominalism. He is also a deep commentator of Arabic or high medieval works. He enjoyed the reputation of being the greatest metaphysician of his time. He thus founded a school of his own, Suarezianism, the chief characteristic principles of which are:

- the principle of individuation by the proper concrete entity of beings;

- the rejection of pure potentiality of matter;

- the singular as the object of direct intellectual cognition;

- a distinctio rationis ratiocinatae between the essence and the existence of created beings;

- the possibility of spiritual substance only numerically distinct from one another;

- ambition for the hypostatic union as the sin of the fallen angels;

- the Incarnation of the Word, even if Adam had not sinned;

- the solemnity of the vow only in ecclesiastical law;

- the system of Congruism that modifies Molinism by the introduction of subjective circumstances, as well as of place and of time, propitious to the action of efficacious grace, and with predestination ante praevisa merita;

- the possibility of holding one and the same truth by both science and faith;

- the belief in Divine authority contained in an act of faith;

- the production of the body and blood of Christ by transubstantiation as constituting the Eucharistic sacrifice;

- the final grace of the Blessed Virgin Mary superior to that of the angels and saints combined.

Suárez made an important classification of being in Disputationes Metaphysicae (1597), which influenced the further development of theology within Catholicism (his fellow Jesuit Pedro da Fonseca having a powerful effect on Protestant Scholastic thought in the 16th and 17th centuries). In the second part of the book, disputations 28 - 53, Suárez fixes the distinction between ens infinitum (God) and ens finitum (created beings). The first division of being is that between ens infinitum and ens finitum. Instead of dividing being into infinite and finite, it can also be divided into ens a se and ens ab alio, i.e., being that is from itself and being that is from another. A second distinction corresponding to this one: ens necessarium and ens contingens, i.e., necessary being and contingent being. Still another formulation of the distinction is between ens per essentiam and ens per participationem, i.e., being that exists by reason of its essence and being that exists only by participation in a being that exists on its own (eigentlich). A further distinction is between ens increatum and ens creatum, i.e., uncreated being and created, or creaturely, being. A final distinction is between being as actus purus and being as ens potentiale, i.e., being as pure actuality and being as potential being. Suárez decided in favor of the first classification of the being into ens infinitum and ens finitum as the most fundamental, in connection with which he accords the other classifications their due.

In theology, Suárez attached himself to the doctrine of Luis Molina, the celebrated Jesuit professor of Évora. Molina tried to reconcile the doctrine of predestination with the freedom of the human will and the predestinarian teachings of the Dominicans by

saying that the predestination is consequent upon God's foreknowledge

of the free determination of man's will, which is therefore in no way

affected by the fact of such predestination. Suárez endeavoured

to reconcile this view with the more orthodox doctrines of the efficacy

of grace and special election, maintaining that, though all share in an

absolutely sufficient grace, there is granted to the elect a grace

which is so adapted to their peculiar dispositions and circumstances

that they infallibly, though at the same time quite freely, yield

themselves to its influence. This mediatizing system was known by the

name of "congruism." Here Suárez' main importance stems probably from his work on natural law, and from his arguments concerning positive law and the status of a monarch. In his extensive work Tractatus de legibus ac deo legislatore (reprinted, London, 1679) he is to some extent the precursor of Grotius and Samuel Pufendorf,

in making an important distinction between natural law and

international law, which he saw as based on custom. Though his method

is throughout scholastic, he covers the same ground, and Grotius speaks

of him in terms of high respect. The fundamental position of the work

is that all legislative as well as all paternal power is derived from

God, and that the authority of every law resolves itself into His.

Suárez refutes the patriarchal theory of government and the

divine right of kings founded upon it --- doctrines popular at that

time

in England and to some extent on the Continent. He argued against the

sort of social contract theory that became dominant among early modern political philosophers such as Thomas Hobbes and John Locke, but some of his thinking found echoes in the more liberal, Lockean contract theorists. Human

beings, argued Suárez, have a natural social nature bestowed

upon them by God, and this includes the potential to make laws. But

when a political society is formed, the authority of the state is not

of divine but of human origin; therefore, its nature is chosen by the

people involved, and their natural legislative power is given to the

ruler. Because

they gave this power, they have the right to take it back, to revolt

against a ruler — but only if the ruler behaves badly towards them, and

they're obliged to act moderately and justly. In particular, the people

must refrain from killing the ruler, no matter how tyrannical he may

have become. If a government is imposed on people, on the other hand,

they not only have the right to defend themselves by revolting against

it, they are entitled to kill the tyrannical ruler. In 1613, at the instigation of Pope Paul V, Suárez wrote a treatise dedicated to the Christian princes of Europe, entitled Defensio catholicae fidei contra anglicanae sectae errores. This was directed against the oath of allegiance which James I required

from his subjects. James (himself a talented scholar) caused it to be

burned by the common hangman, and forbade its perusal under the

'severest penalties, complaining bitterly to Philip III that he should harbour in his dominions a declared enemy of the throne and majesty of kings.

The Disputationes Metaphysicae (1597)

were published in the Seventeenth Century by the Portugal Jesuits. In

the Eighteen Century, the Venice edition in 23 volumes in folio

(1740 – 1757) appeared, followed by the Parisian Vivès edition, 28

volumes (1856 – 1861); in 1965 the Vivés edition of the Disputationes Metaphysicae was

reprinted by Georg Olms, Hildesheim. No modern edition of

Suárez's complete works is yet available. Several current to

semi - current translations of Suárez's Disputations have

recently been re-translated or translated into English for the first

time. An

effort is underway to try and provide a complete contemporary English

translation of the "Disputationes Metaphysicae". The

contributions of Suarez to metaphysics and theology exerted significant

influence over 18th century scholastic theology among both Roman

Catholics and Protestants. Among early Protestant scholastics the influence of his Disputationes Metaphysicae is evident in the writings of Bartholomaeus Keckermann (1571 – 1609), Clemens Timpler (1563 – 1624), Gilbertus Jacchaeus (1578 – 1628), Johann Heinrich Alsted (1588 – 1638), Antonius Walaeus (1573 – 1639), and Johannes Maccovius (Jan Makowski; 1588 – 1644), among others. This influence was so pervasive that by 1643 it provoked the Dutch Reformed theologian Jacobus Revius to publish his book length response: Suarez repurgatus.