<Back to Index>

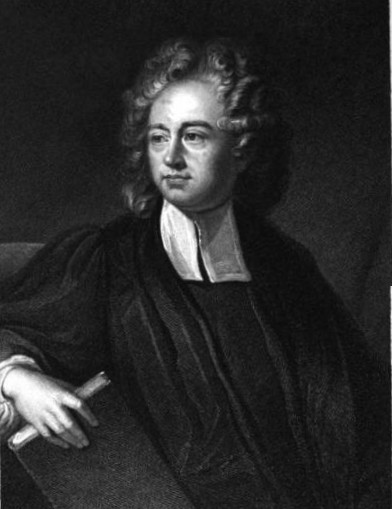

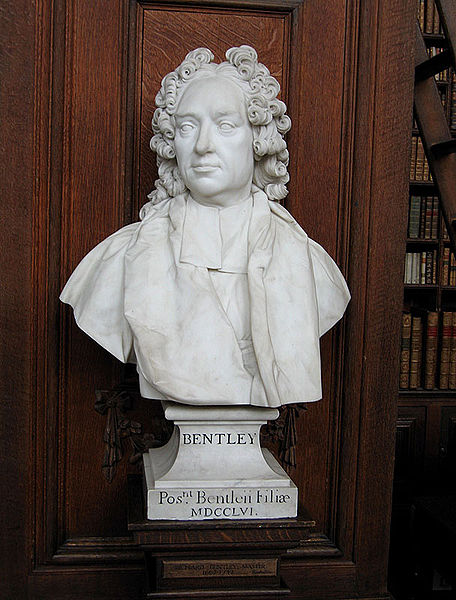

- Classical Scholar Richard Bentley, 1662

- Painter Hendrick Avercamp, 1585

- General of the Portuguese Army Gomes Freire de Andrade, 1757

PAGE SPONSOR

Richard Bentley (27 January 1662 – 14 July 1742) was an English classical scholar, critic, and theologian. He was long the master of Trinity College, Cambridge.

Bentley was the first Englishman to be ranked with the great heroes of classical learning and was known for his literary and textual criticism. Called the "founder of historical philology", Bentley is credited with the creation of the English school of Hellenism. He inspired generations of subsequent scholars. Bentley was born at Oulton near Rothwell, Leeds, West Yorkshire, northern England. His grandfather had suffered for the Royalist cause following the English Civil War, leaving the family in reduced circumstances. Bentley's mother, the daughter of a stonemason, had some education, and was able to give her son his first lessons in Latin. After attending grammar school in Wakefield, Bentley was an undergraduate at St John's College, Cambridge in 1676. He afterward obtained a scholarship and took the degree of B.A. in 1680 (M.A. 1683).

He never became a

Fellow, but was appointed to be the headmaster of Spalding Grammar School before he was 21. Edward Stillingfleet, dean of St Paul's, hired Bentley as tutor to his son, which enabled the

younger man to meet eminent scholars, have access to the best private

library in England, and become familiar with Dean Stillingfleet. During

his six years as tutor, Bentley also made a comprehensive study of Greek and Latin writers, storing up knowledge which he used later. In 1689, Stillingfleet became bishop of Worcester, and Bentley's pupil went to Wadham College, Oxford, accompanied by his tutor. Bentley soon met Dr John Mill, Humphrey Hody, and Edward Bernard. Here he studied the manuscripts of the Bodleian, Corpus Christi and

other college libraries. He collected material for literary studies.

Among these are a corpus of the fragments of the Greek poets and an

edition of the Greek lexicographers. The Oxford (Sheldonian) press was about to bring out an edition (the editio princeps) from the unique manuscript of the Greek Chronicle in the Bodleian Library. It was a universal history (down to AD 560) of John of Antioch (date uncertain, between 600 and 1000), called John Malalas or "John the Rhetor". The editor, Dr John Mill, principal of St Edmund Hall, asked Bentley to review it and make any remarks on the text. Bentley wrote the Epistola ad Johannem Millium, which is about 100 pages included at the end of the Oxford Malalas (1691).

This short treatise placed Bentley ahead of all living English

scholars. The ease with which he restored corrupted passages, the

certainty of his emendation and command over the relevant material, are in a style totally different from the careful and laborious learning of Hody, Mill or Edmund Chilmead.

To the small circle of classical students (lacking the great critical

dictionaries of modern times), it was obvious that he was a critic

beyond the ordinary. In 1690, Bentley had taken deacon's orders. In 1692 he was nominated first Boyle lecturer,

a nomination repeated in 1694. He was offered the appointment a third

time in 1695 but declined it, as he was involved in too many other

activities. In the first series of lectures ("A Confutation of

Atheism"), he endeavours to present Newtonian physics in a popular form, and to frame them (especially in opposition to Hobbes) into proof of the existence of an intelligent Creator. He had some correspondence with Newton, then living in Trinity College, Cambridge, on the subject. The second series, preached in 1694, has not been published and is believed to be lost. After being ordained, Bentley was promoted to a prebendal stall in Worcester Cathedral.

In 1693 the curator of the royal library became vacant, and his friends

tried to obtain the position for Bentley, but did not have enough

influence. The new librarian, a Mr Thynne, resigned in favour of

Bentley, on condition that he receive an annuity of £130 for life

out of the £200 salary. In 1695 Bentley received a royal chaplaincy and the living of Hartlebury. That same year, he was elected a fellow of the Royal Society, and in 1696 earned the degree of D.D. (Doctor of Divinity). The scholar Johann Georg Graevius of Utrecht made a dedication to him, prefixed to a dissertation on Albert Rubens, De Vita Flavii Mattii Theodori (1694), which showed Bentley's work had been recognized on the Continent. Bentley had official apartments in St. James's Palace, and his first care was the royal library. He worked to restore the collection from a dilapidated condition. He persuaded the Earl of Marlborough to

ask for additional rooms in the palace for the books. This was granted,

but Marlborough kept them for personal use. Bentley enforced the law,

ensuring that publishers delivered nearly 1000 volumes which had been

purchased but not delivered. The University of Cambridge commissioned him to obtain Greek and Latin fonts for their classical books; he had these made in Holland. He assisted John Evelyn in his Numismata.

Bentley did not settle down to the steady execution of any of the major

projects he had started. In 1694, he designed an edition of Philostratus, but abandoned it to Gottfried Olearius (1672 – 1715), "to the joy," says F. A. Wolf, "of Olearius and of no one else." He supplied Graevius with collations of Cicero, and Joshua Barnes with a warning as to the spuriousness of the Epistles of Euripides. Barnes printed the epistles anyway and declared that no one could doubt their authenticity but a man perfrictae frontis aut judicii imminuti. For Graevius's Callimachus (1697), Bentley added a collection of the fragments with notes. He wrote the Dissertation on the Epistles of Phalaris, his major academic work, almost accidentally. In 1697, William Wotton, about to bring out a second edition of his Ancient and Modern Learning, asked Bentley to write out a paper exposing the spuriousness of the Epistles of Phalaris, long a subject of academic controversy. The Christ Church College editor of Phalaris, Charles Boyle,

resented Bentley's paper. He had already quarreled with Bentley in

trying to get the manuscript in the royal library collated for his

edition (1695). Boyle wrote a response which was accepted by the

reading public, although it was much later criticized as showing

superficial learning.)

The demand for Boyle's book required a second printing. When Bentley

responded, it was with his dissertation. The truth of its conclusions

was not immediately recognized but it has a high reputation. In 1700, the commissioners of ecclesiastical patronage recommended Bentley to the Crown for the mastership of Trinity College, Cambridge.

He arrived an outsider and proceeded to reform the college

administration. He started a program of renovations to the buildings,

and used his position to promote learning. At the same time, he

antagonized the fellows, and the capital programme caused reductions in

their incomes, which they resented. After ten years of stubborn but ineffectual resistance, the fellows appealed to the Visitor, the bishop of Ely (John Moore). Their petition was full of general complaints. Bentley's reply (The Present State of Trinity College,

etc., 1710) is in his most crushing style. The fellows amended their

petition and added a charge of Bentley's having committed 54 breaches

of the statutes. Bentley appealed directly to the Crown, and backed his

application with a dedication of his Horace to the lord treasurer (Harley). The

Crown lawyers decided against him; the case was heard (1714) and a

sentence of expulsion from the mastership was drawn up. Before it was

executed, the bishop of Ely died and the process lapsed. The feud

continued in various forms at lower levels. In 1718 Cambridge rescinded

Bentley's degrees, as punishment for failing to appear in the

vice - chancellor's court in a civil suit. It was not until 1724 that he

had them restored under the law. In 1733 the fellows of Trinity again brought Bentley to trial before the bishop of Ely (then Thomas Greene), and he was sentenced to deprivation. The college statutes required the sentence to be exercised by the vice - master Richard Walker,

who was a friend of Bentley and refused to act. Although the feud

continued until 1738 or 1740 (about thirty years in all), Bentley

remained in his post. During

his mastership, except for the first two years, Bentley continuously

pursued his studies, although he did not publish much. In 1709 he

contributed a critical appendix to John Davies's edition of Cicero's Tusculan Disputations. In the following year, he published his emendations on the Plutus and Nubes of Aristophanes, and on the fragments of Menander and Philemon. He published the last work under the pen name of "Phileutherus Lipsiensis." He used it again two years later in his Remarks on a late Discourse of Freethinking, a reply toAnthony Collins the deist. The university thanked him for this work and its support of the Anglican Church and clergy. Although

he had long studied Horace, Bentley wrote his version quickly in the

end, publishing it in 1711 to gain public support at a critical period

of the Trinity quarrel. In the preface, he declared his intention of

confining his attention to criticism and correction of the text. Some

of his 700 or 800 emendations have

been accepted, but the majority were rejected by the early 20th century

as unnecessary, although scholars acknowledged they showed his wide

learning. In 1716, in a letter to William Wake, Archbishop of Canterbury, Bentley announced his plan to prepare a critical edition of the New Testament. During the next four years, assisted by J.J. Wetstein, an eminent biblical critic, he collected materials for the work. In 1720 he published Proposals for a New Edition of the Greek Testament, with examples of how he intended to proceed. By comparing the text of the Vulgate with

that of the oldest Greek manuscripts, Bentley proposed to restore the

Greek text as received by the church at the time of the Council of Nice. Bentley's lead manuscript was Codex Alexandrinus, which he described as "the oldest and best in the world." Bentley used also manuscripts: 51, 54, 60, 113, 440, 507, and 508. Numerous subscribers were obtained to support publication of the work, but he never completed it. His Terence (1726) is more important than his Horace; next to the Phalaris, this most determined his reputation. In 1726 he also published the Fables of Phaedrus and the Sentenliae of Publilius Syrus. His Paradise Lost (1732), suggested by Queen Caroline, has been criticized as the weakest of his work. He suggested that the poet John Milton had employed both an amanuensis and

an editor, who were responsible for clerical errors and interpolations,

but it is unclear whether Bentley believed his own position. He never

published his planned edition of Homer,

but some of his manuscript and marginal notes are held by Trinity

College. Their chief importance is in his attempt to restore the metre

by the insertion of the lost digamma.

Bentley

was self-assertive and presumptuous, which alienated some people. But,

James Henry Monk, Bentley's biographer, charged him (in his first

edition, 1830) with an indecorum of which he was not guilty. Bentley

seemed to inspire mixed feelings of admiration and repugnance. In 1701, Bentley married Joanna Bernard, daughter of Sir John Bernard, 2nd Baronet of Brampton, Huntingdonshire. They

had three children together: Richard (1708 – 1782), an eccentric,

playwright and artist whose engravings for Thomas Gray’s ‘A Long Story’ were published in 1753, and two daughters, one named Johanna. His wife died in 1740. Johanna Bentley married Denison Cumberland in

1728. He became Master of Trinity College and later served in two

bishoprics. He was a grandson of Richard Cumberland, bishop of Peterborough. Their son Richard Cumberland developed as a prolific dramatist, while earning his living as a civil servant.

In

old age, Bentley continued to read; and enjoyed the society of his

friends and several rising scholars, J Markland, John Taylor, and his

nephews Richard and Thomas Bentley, with whom he discussed classical

subjects. He died at 80 of pleurisy. Bentley was the first Englishman to be ranked with the great heroes of classical learning. Before him there were only John Selden, and, in a more restricted field, Thomas Gataker and

Pearson. "Bentley inaugurated a new era of the art of criticism. He

opened a new path. With him criticism attained its majority. Where

scholars had hitherto offered suggestions and conjectures, Bentley,

with unlimited control over the whole material of learning, gave

decisions". The modern German school of philology recognised his genius. Bunsen wrote that Bentley "was the founder of historical philology." Jakob Bernays says of his corrections of the Tristia,

"corruptions which had hitherto defied every attempt even of the

mightiest, were removed by a touch of the fingers of this British Samson." Bentley

was credited with creating the English school of Hellenists, by which

the 18th century was distinguished, including scholars such as R Dawes, J Markland, J Taylor, J Toup, T Tyrwhitt, Richard Porson, PP Dobree, Thomas Kidd and JH Monk. Although the Dutch school of the period had its own tradition, it was also influenced by Bentley. His letters to the young Hemsterhuis on his edition of Julius Pollux made the latter one of Bentley's most devoted admirers. Bentley

inspired a following generation of scholars. Self - taught, he created

his own discipline; but no contemporary English guild of learning could

measure his power or check his eccentricities. He defeated his academic

adversaries in the Phalaris controversy. The attacks by Alexander Pope (he was assigned a niche in The Dunciad), John Arbuthnot and

others demonstrated their inability to appreciate his work, as they

considered textual criticism as pedantry. His classical controversies

also called forth Jonathan Swift's Battle of the Books. In

a university where the instruction of youth or the religious

controversy of the day was the chief occupation, Bentley was unique.

His learning and original views seem to have been developed before

1700. After this period, he acquired little and made only spasmodic

efforts to publish. But, the critic A.E. Housman believed that the edition of Manilius (1739) was Bentley's greatest work.