<Back to Index>

- Physicist Mohammad Abdus Salam, 1926

- Writer Johann Gottfried Seume, 1763

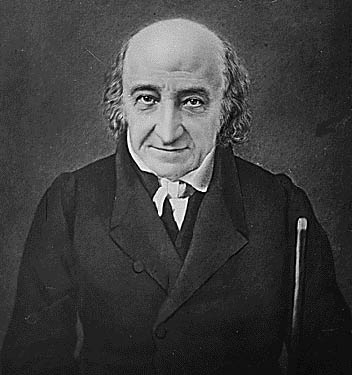

- 4th U.S. Secretary of the Treasury Abraham Alfonse Albert Gallatin, 1761

PAGE SPONSOR

Abraham Alfonse Albert Gallatin (January 29, 1761 – August 12, 1849) was a Swiss - American ethnologist, linguist, politician, diplomat, congressman, and the longest - serving United States Secretary of the Treasury. In 1831, he founded the University of the City of New York. In 1896, this university was renamed New York University; it is now one of the largest private, non - profit universities in the United States.

Born in Switzerland, Gallatin immigrated to America in the 1780s, ultimately settling in Pennsylvania. He was politically active against the Federalist Party program, and was elected to the United States Senate in

1793, but was removed from office by a 14 – 12 party line vote after a

protest raised by his opponents suggested he had fewer than the

required nine years of citizenship. In 1795 he was elected to the House of Representatives and served in the fourth through sixth Congresses, becoming House Majority Leader. He was an important leader of the new Democratic - Republican Party, its chief spokesman on financial matters, and led opposition to many of the policy proposals of Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton. He also helped found the House Committee on Finance (later the Ways and Means Committee)

and often engineered withholding of finances by the House as a method

of overriding executive actions to which he objected. While Treasury

Secretary, his services to his country were honored in 1805 when Meriwether Lewis named one of the three headwaters of the Missouri River after Gallatin. Gallatin was born in Geneva, Switzerland, to the wealthy Jean Gallatin and his wife, Sophie Albertine Rollaz. Gallatin's

family had great influence in Switzerland, and many family members held

distinguished positions in the magistracy, military, and in Swiss

delegations of foreign armies. His parents married in 1753. Gallatin's

father, a prosperous merchant, died in 1765, followed by his mother in

April 1770. Gallatin, now orphaned, was taken into the care of

Mademoiselle Pictet, a family friend and distant relative of Gallatin's

father. Here, Gallatin remained, until January 1773 when he was sent to

boarding school. While a student at the elite Academy of Geneva, Gallatin read deeply in philosophy of Jean - Jacques Rousseau and the French Physiocrats; he became dissatisfied with the traditionalism of Geneva. As a student of the Enlightenment,

he believed in human nature and believed that when free from social

trammels, it would display nobler qualities and achieve vaster results,

not merely in the physical but also in the moral world. Thus the

democratic spirit of America attracted him in 1780 at the age of 19. In

April 1780, he secretly left Geneva with his classmate Henri Serre.

Armed with letters of recommendation from eminent Colonials (including Benjamin Franklin)

that the Gallatin family procured, the two young men departed France in

May, setting sail for the then Colonies in an American ship, "the

Kattie". They reached Cape Ann on July 14 and arrived in Boston the next day, traveling the intervening thirty miles by horseback.

Bored with monotonous Bostonian life, the men set sail with a Swiss female companion, to the settlement of

Machias, located on the northeastern tip of the Maine frontier.

At Machias, Gallatin operated a bartering venture, in which he dealt

with a variety of goods and supplies. He enjoyed the simple life and

the natural environment surrounding him. During

the winter of 1780 - 81 Gallatin served in the defense of his new country

and even commanded a garrison in Maine for a time. Gallatin

and Serre returned to Boston in October 1781, after abandoning their

bartering venture in Machias. Gallatin supported himself by giving

French language lessons. Soon afterward, he sent a letter to

Mademoiselle Pictet, offering a frank account of the troubles he was

having in America. Pictet sensed this would be the case, and she had

already contacted Dr. Samuel Cooper,

a distinguished Bostonian patriot, whose grandson was a student in

Geneva. With Cooper's influence, Gallatin was able to secure a faculty

position in July 1782 at Harvard College, where he taught French. Gallatin used his early salary to purchase 370 acres (1.5 km2) of land in Fayette County, Pennsylvania, near Point Marion south of Pittsburgh which

he thought well suited for farming and as a staging area for selling

land and goods. Gallatin honored his friends by naming the new property Friendship Hill. He moved there in 1784. In

the spring of 1789, Gallatin eloped with Sophia Allegre, the attractive

daughter of his landlady, who disapproved of him. However, she fell ill

and died later that year. He was in mourning for several years and

seriously considered returning to Geneva. However, on November 1, 1793,

he married Hannah Nicholson, daughter of the well connected Commodore James Nicholson. They would have two sons and a daughter. In 1794, Gallatin was hearing rumors of mass exodus of Europeans fleeing the French Revolution.

An idea struck his fancy; perhaps he should develop a settlement for

these emigrants. Throughout the spring and summer of 1795 Gallatin

pondered, planned and finally selected Wilson's Port, a small river

town located one mile (1.6 km) north of his Friendship Hill.

Collecting four other investors, three of which were also Swiss,

Gallatin had the partnership incorporated as Albert Gallatin &

Company. Together they purchased Wilson's Port, Georgetown and vacant

lots across the river in Greensboro. The partners named their new settlement New Geneva. With a company store, boat yard and mills along Georges Creek, the partners awaited the rush of settlers. An

improved European situation and mild economic recession in 1796 - 1797

did not bring the expected wealth to the Gallatin partnership. As

Gallatin struggled with the Federalists in the Congress, his partners

happened upon six German glassblowers traveling to Kentucky.

Convinced that glass would revive their sagging investment, the

partners asked the Germans to set up shop in New Geneva. Gallatin was

appalled with the idea, and considered it to be a gamble. Nonetheless,

production of glass began on January 18, 1798. Window glass, whiskey

bottles and other hollow ware were produced. This was the first glass

blown west of the Alleghenies. The

glass business was not without its problems. Poor initial profits,

material shortages and a labor "insurrection" combined to make Gallatin

believe that the glass industry should be abandoned. By 1800, though,

the business had made a turnaround. With the availability of coal

across the river, the glass works were moved to Greensboro in 1807.

Later in 1816 Gallatin would call the glass works his most "productive

property". Another industry to make its appearance at the New Geneva complex was the manufacture of muskets. In 1797 a crisis with France had flared into an undeclared war. The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania called out to its militia, only to find a shortage of muskets, bayonets and cartridge boxes. Contracts were awarded to private manufacturers to produce 12,000 stands of arms. Seeing

an opportunity to relieve festering debts from the land and glass

businesses, the western partners sought Gallatin's advice and political

pull in the state government to acquire an arms contract. Initially

against the idea, the mounting debts forced Gallatin to reconsider. He

signed a contract in January 1799 to produce 2000 muskets with

bayonets. The Gallatin partners subcontracted Melchior Baker of Haydentown to

make the muskets. Lack of skilled labor and quality steel supported by

poor management plagued the business. By April, 1801 only 600 muskets

had been delivered, fifteen months behind schedule. Seeing only

complete financial ruin if he remained in the agreement, Gallatin

transferred all contractual obligations to Melchior Baker and Abraham

Stewart. During

his fifth year as Minister to France, Albert Gallatin longed for

retirement to Friendship Hill. Hoping to live off the profits of the

glass business, Gallatin made substantial improvements to the house and

grounds. It was not a happy homecoming. The economic "Panic of 1819"

caught up with the glass business and forced its closure in 1821. While

"contented to live and die amongst the Monongahela hills" Albert

Gallatin sold his beloved Friendship Hill and other western holdings at

great financial loss. In 1793, Gallatin won election to the United States Senate. When the Third Congress opened on December 2, 1793, he took the oath of office,

but, on that same day, nineteen Pennsylvania Federalists filed a

protest with the Senate that Gallatin did not have the minimum nine

years of citizenship required to be a senator. The petition was sent to

committee, which duly reported that Gallatin had not been a citizen for

the required period. Gallatin rebutted the committee report, noting his

unbroken residence of thirteen years in the United States, his 1785

oath of allegiance to the Commonwealth of Virginia, his service in the

Pennsylvania legislature, and his substantial property holdings in the

United States. The report and Gallatin's rebuttal were sent to a second

committee. This committee also reported that Gallatin should be

removed. The matter then went before the full Senate where Gallatin was

removed in a party line vote of 14 – 12. Gallatin's brief stint in the Senate was not without consequence. Gallatin had proven to be an effective opponent of Alexander Hamilton's financial policies, and the election controversy added to his fame. The

dispute itself had important ramifications. At the time, the Senate

held closed sessions. However, with the American Revolution only a

decade ended, the senators were leery of anything which might hint that

they intended to establish an aristocracy, so they opened up their

chamber for the first time for the debate over whether to unseat

Gallatin. Soon after, open sessions became standard procedure for the

Senate.

Returning

home, he found western Pennsylvanians (mostly Scotch Irish) angry at

the whiskey tax imposed in 1791 by Congress at the demand of

Alexander Hamilton to

raise money to pay the national debt. Farmers could only export whiskey

because transportation costs were too high for grain. Although Gallatin

had opposed the tax before it was passed and attended numerous protest

meetings, he counseled moderation. Nevertheless, the role he played in

the Whiskey Rebellion in the early 1790s proved a lasting political liability, as President George Washington denounced

the tax protesters, called out the militia, and marched at the head of

the army to put down the rebellion. A group of radicals, headed by a

blatant demagogue named David Bradford, staged incendiary meetings, to

which they summoned the local militia, terrorized conservatives in

Pittsburgh, threatened federal revenue officers with death, and called

for rebellion. Gallatin

calmed the westerners; with courage and persuasive oratory, he faced

the excited and armed mobs, heartened the moderates, won over the

wavering, and at last secured a vote of 34 to 23 in the revolutionary

committee of sixty for peaceable submission to the law of the country.

The rebellion collapsed as the army moved near, Bradford fled, and

there was no fighting. Gallatin's neighbors approved his advocacy of

their cause and elected him to the U.S. House of Representatives for

three terms, 1795 - 1801. Entering the House of Representatives in 1795, he served in the fourth through sixth Congresses. He was the major spokesman on finance for the new Jeffersonian Democratic - Republican Party, headed by James Madison. By 1797, when Madison retired, Gallatin became the party leader in the House, a position now known as House Majority Leader. He strongly opposed the domestic programs of the Federalist Party, as well as the Jay Treaty of 1795, which he thought was a sellout to the British. When the Quasi War with France erupted in 1798 he kept a low profile, but did oppose the Alien and Sedition Acts. Although Gallatin opposed the entire program of Alexander Hamilton in the 1790s, when he came to power in 1801 he found himself keeping all the main parts, and supporting the Bank of the United States, which other Jeffersonians vehemently opposed. As party leader, Gallatin put a great deal of pressure on President John Adams' Treasury Secretary Oliver Wolcott, Jr. to maintain fiscal responsibility. He also helped found the House Committee on Finance (which would evolve into the Ways and Means Committee)

and often engineered withholding of finances by the House as a method

of overriding executive actions to which he objected. His measures to

withhold naval appropriations during this period were met with vehement

animosity by the Federalists, who accused him of being a French spy.

Gallatin's

mastery of public finance, an ability rare among members of the

Jeffersonian party, led to his automatic choice as Secretary of the

Treasury, despite Federalist attacks that he was a "foreigner" with a

French accent. He was secretary from 1801 to May 1813 (and nominally

until February 1814) under presidents Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, the longest tenure of this office in American history.

The

national debt was seen as an indicator of waste and corruption, and

Jeffersonians wanted it paid off totally. They also wanted to buy

Louisiana and fight a war with Britain, and Gallatin managed to finance

these grand objectives, but he could not simultaneously pay off the

debt. The debt stood at $80 million in 1801, and Gallatin devoted 3/4

of federal revenues to reducing it. Despite spending $15 million on

Louisiana, and losing the tax on whiskey when it was repealed in 1802,

Gallatin trimmed the debt to $45 million. The government saved money by

mothballing the Navy and keeping the Army small and poorly equipped.

Gallatin reluctantly supported Jefferson's embargo of 1807 - 1808, which

tried to use economic coercion to change British policies, and failed

to do so. The War of 1812 (1812 – 1815) proved expensive, and the debt soared to $123 million, even with burdensome new taxes.

Gallatin helped plan the Lewis and Clark Expedition, mapping out the area to be explored. Upon finding the source of the Missouri River at present day Three Forks, Montana, Captains Lewis and Clark named the eastern of the three tributaries after Gallatin; the other two were named after President Jefferson and James Madison, the Secretary of State (and next President). The Gallatin River descends from Yellowstone National Park, followed north by U.S. Highway 191 past the Big Sky Resort, towards Bozeman. A few miles southwest of the city the river turns northwest, where Interstate 90 follows it to Three Forks.

In

1808 Gallatin proposed a dramatic $20 million program of internal

improvements — that is, roads and canals along the Atlantic seacoast and

across the Appalachian mountain

barrier to be financed by the federal government. It was rejected by

the "Old Republican" faction of his party that deeply distrusted the

national government, and anyway there was no money to pay for it. Most

of Gallatin's proposals were eventually carried out years later, but

this was done not by the concerted federal action he proposed, but by

local governmental and private action. Though often wasteful, this

method enlisted local and private energies in large enterprises. While

not a pacifist, he strongly opposed building up a navy and endorsed

Jefferson's scheme of using small gunboats to protect major ports. (The

plan failed in the War of 1812 as the British landed behind the harbors

unhindered.) In 1812, the U.S. was financially unprepared for war. For example, the Democratic Republicans allowed the First Bank of the United States to

expire in 1811, over Gallatin's objections. He had to ship $7 million

to Europe to pay off its foreign stockholders just at a time money was

needed for war. The heavy military expenditures for the War of 1812,

and the decline in tariff revenue caused by the embargo and the British blockade cut off legitimate trade (there was plenty of smuggling, but smugglers never paid taxes.) In

1813, the Treasury had expenditures of $39 million and revenue of only

$15 million. Despite anger from Congress, Gallatin was forced to

reintroduce the Federalist taxes he had denounced in 1798, such as the taxes on

whiskey and salt, as well as a direct tax on land and slaves. Absent a

national bank, and with the refusal of New England financiers to loan

money for the war effort, Gallatin resorted to innovative methods to

finance the war. In March 1813, he initiated the public bidding system

that was to characterize subsequent government borrowings. A financial

syndicate subscribed for 57% of the $16,000,000 loan, of which

$5,720,000 came from New York City, $6,858,000 from Philadelphia, and

$75,000 from Boston. He succeeded in funding the deficit of $69 million

by bond issues, and thereby paid the direct cost of the war, which

amounted to $87 million. Realizing the need for a national bank, he

helped charter the Second Bank of the United States, in 1816. In 1813, President James Madison sent him as the United States representative to a Russian brokered

peace talk, which Britain ultimately refused, preferring direct

negotiations. Gallatin then resigned as Secretary of the Treasury to

head the United States delegation for these negotiations and was

instrumental in securing the Treaty of Ghent,

which brought the War of 1812 to a close. His patience and skill in

dealing not only with the British but also with his fellow members of

the American commission, including Henry Clay and John Quincy Adams, made the Treaty "the special and peculiar triumph of Mr. Gallatin." Declining another term at the Treasury, from 1816 to 1823 Gallatin served as United States Minister to France, struggling with scant success to improve relations with the Bourbon Restoration government. Gallatin returned to America in 1823 and was nominated for Vice President by the Republican Congressional caucus that had chosen William H. Crawford as

its Presidential candidate. Gallatin never wanted the role and was

humiliated when he was forced to withdraw from the race because he

lacked popular support. Gallatin was alarmed at the possibility Andrew Jackson might

win; he saw Jackson as "an honest man and the idol of the worshippers

of military glory, but from incapacity, military habits, and habitual

disregard of laws and constitutional provisions, altogether unfit for

the office." He returned home to Pennsylvania where he lived until 1826. By 1826, there was much contention between the United States and Britain over claims to the Columbia River system

on the Northwest coast. Gallatin put forward a claim in favor of

American ownership, outlining what has been called the "principle of

contiguity" in his statement called "The Land West of the Rockies". It

states that lands adjacent to already settled territory can reasonably

be claimed by the settled territory. This argument is an early version

of the doctrine of America's "manifest destiny".

This principle became the legal premise by which the United States was

able to claim the lands to the west. In 1826 and 1827, he served as

minister to the Court of St. James's (i.e.,

minister to Great Britain) and negotiated several useful agreements,

such as a ten year extension of the joint occupation of Oregon.

He then settled in New York City, where he helped found New York University in

1831, in order to offer university education to the working and

merchant classes as well as the wealthy. He became president of the

National Bank (which was later renamed Gallatin Bank). In 1849,

Gallatin died in Astoria in what is now the Borough of Queens, New York; he is interred at Trinity Churchyard in

New York City. Prior to his death, Gallatin had been the last surviving

member of the Jefferson Cabinet and the last surviving Senator from the

18th century. His

last great endeavor was founding the American science of ethnology,

with his studies of the languages of the Native Americans; he has been

called "the father of American ethnology." Throughout his career, Gallatin pursued an interest in Native American language and culture. He drew upon government contacts in his research, gathering information through Lewis Cass, explorer William Clark, and Thomas McKenney of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Gallatin developed a personal relationship with Cherokee tribal leader John Ridge,

who provided him with information on the vocabulary and structure of

the Cherokee language. Gallatin's research resulted in two published

works: A Table of Indian Languages of the United States (1826) and Synopsis of the Indian Tribes of North America (1836).

His research led him to conclude that the natives of North and South

America were linguistically and culturally related, and that their

common ancestors had migrated from Asia in prehistoric times. In 1842, Gallatin joined with John Russell Bartlett to found the American Ethnological Society. Later research efforts include examination of selected Pueblo societies, the Akimel O'odham (Pima) peoples, and the Maricopa of the Southwest. In politics, Gallatin stood for assimilation of

Native Americans into European based American society, encouraging

federal efforts in education leading to assimilation and denying

annuities for Native Americans displaced by western expansion.

Almost immediately, Gallatin became active in Pennsylvania politics; he was a member of the state constitutional convention in 1789, and was elected to the Pennsylvania General Assembly in 1790.