<Back to Index>

- Inventor Joseph Marie Charles Jacquard, 1752

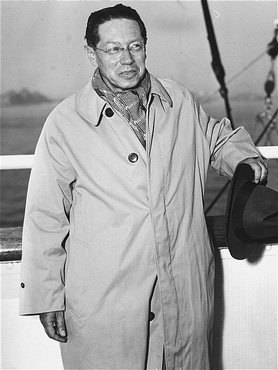

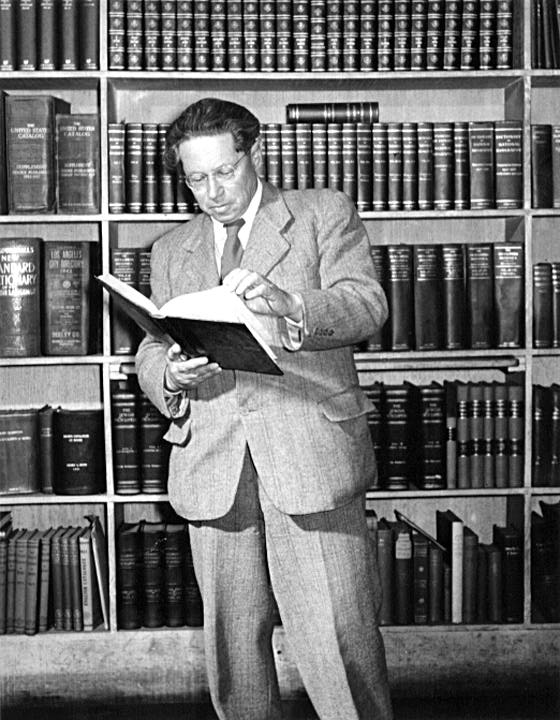

- Writer Lion Feuchtwanger, 1884

- General of the Union Cavalry Alfred Pleasonton, 1824

PAGE SPONSOR

Lion Feuchtwanger (7 July 1884 – 21 December 1958) was a German - Jewish novelist and playwright. A prominent figure in the literary world of Weimar Germany, he influenced contemporaries including playwright Bertolt Brecht.

Feuchtwanger's fierce criticism of the Nazi Party — years before it assumed power — ensured that he would be a target of government sponsored persecution after Adolf Hitler's appointment as chancellor of Germany in January 1933. Following a brief period of internment in France, and a harrowing escape from Continental Europe, he sought asylum in the United States, where he died in 1958. Feuchtwanger is often praised for his efforts to expose the brutality of the Nazis and occasionally criticized for his failure to acknowledge the brutality of the Soviets and the Communist Party under Joseph Stalin.

Feuchtwanger's ancestors originated from the

Middle Franconian city of Feuchtwangen which, following a pogrom in 1555, expelled all its resident Jews. Some of the expellees subsequently settled in Fürth where they were called the Feuchtwangers, meaning those from Feuchtwangen. Feuchtwanger's grandfather Elkan moved to Munich in the middle of 19th century, where

Lion Feuchtwanger was born in 1884, and raised in a Jewish household.

He studied literature and philosophy in the universities in Munich and Berlin.

Feuchtwanger served in the German Army during World War I, an experience that contributed to a leftist tilt in his writings. After studying a variety of subjects, he became a theatre critic and founded the culture magazine, "Der Spiegel", in 1908. He soon became a figure in the literary world, and was sought out by the young Bertolt Brecht, with whom he collaborated on drafts of Brecht's early work, The Life of Edward II of England, in 1923 - 24. According to Feuchtwanger's widow, Marta, Feuchtwanger was a possible source for the titles of two other Brecht works, including Drums in the Night (first called Spartakus by Brecht).

Feuchtwanger was already well known throughout Germany in 1925, when his first popular novel, Jud Süß (Jew Suss), appeared. He also published Erfolg (Success), a fictionalized account of the rise and fall of the Nazi Party (which he considered, in 1930, a thing of the past) during the inflation era. The new fascist regime soon began persecuting him, and while he was on a speaking tour of America, in Washington, D.C., he was a guest of honor at a dinner hosted by then German ambassador Friedrich Wilhelm von Prittwitz und Gaffron. That same day (January 30, 1933) Hitler was appointed Chancellor. The next day, Prittwitz resigned from the diplomatic corps and called Feuchtwanger, recommending that he not return home.

In 1933, while Feuchtwanger was on the tour, his house was ransacked by government agents who stole or destroyed many items from his extensive library, including invaluable manuscripts of some of his projected works (one of the characters in The Oppermanns undergoes an identical experience).

Feuchtwanger and his wife did not return to Germany, moving instead to Southern France, settling in Sanary - sur - Mer. His works were included among those burned during the May 10, 1933 Nazi book burning held across Germany. On August 25, 1933, the official government gazette, Reichsanzeiger, included Feuchtwanger's name on the first list of those whose German citizenship was revoked because of "disloyalty to the German Reich and the German people." Because Feuchtwanger had addressed and predicted many of their crimes even before they came to power, Hitler considered him a personal enemy and the Nazis designated Feuchtwanger as the "Enemy of the state number one", as mentioned in The Devil in France (Der Teufel in Frankreich). Still, Nazi Propaganda Minister Goebbels paid Feuchtwanger the dubious compliment of having his book Jud Süß made into a film in 1940 — albeit, with the introduction of an anti - Semitic slant that did not appear in the original.

In his writings, Feuchtwanger exposed Nazi racist policies years before the official London and Paris governments abandoned their policy of appeasement towards Hitler. He remembered that American politicians also had suggested that "Hitler be given a chance." With the publication of The Oppermanns in 1933, he became a prominent spokesman in opposition to the Third Reich. Within a year, the novel was translated into the Czech, Danish, English, Finnish, Hebrew, Hungarian, Norwegian, Polish and Swedish languages.

In 1936, still in Sanary, he wrote The Pretender (Der falsche Nero), in which he compared the Roman upstart Terentius Maximus, who had claimed to be Nero, with Hitler.

The following year he traveled to the Soviet Union. His notes about life in Moscow, Moskau 1937, show him praising life under Joseph Stalin and approving of the Moscow Trials. The book has been criticized as a work of naive apologism.

When the Germans invaded France in 1940, Feuchtwanger was captured and imprisoned in an internment camp,

Les Milles (Camp des Milles). In 1941, he published a memoir of his internment, The Devil in France (Der Teufel in Frankreich). He escaped Les Milles with the help of his wife Marta; Varian Fry, an American journalist who helped refugees escape from occupied France; Hiram Bingham IV, US Vice Consul in Marseilles; and, the Rev. Waitstill and Mrs. Martha Sharp,

a Unitarian minister and his wife who were in Europe on a similar

mission as Fry. The Rev. Sharp volunteered to accompany Feuchtwanger by

rail from Marseilles across Spain to Lisbon. If Feuchtwanger had been

recognized at border crossings in France or Spain, he would have been

detained and turned over to the Gestapo.

Realizing that even in Portugal, Feuchtwanger was still not out of

reach of the Nazis, Martha Sharp gave up her own berth on the Excalibur, so Feuchtwanger could sail immediately for New York City with her husband.