<Back to Index>

- Physician William Osler, 1849

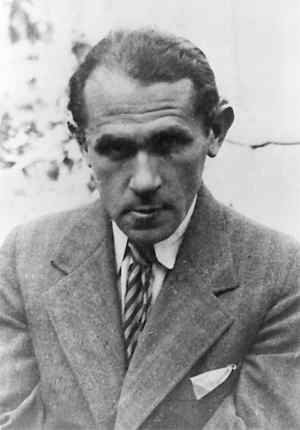

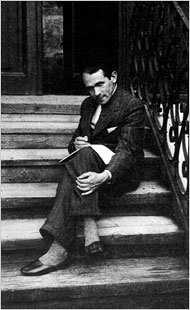

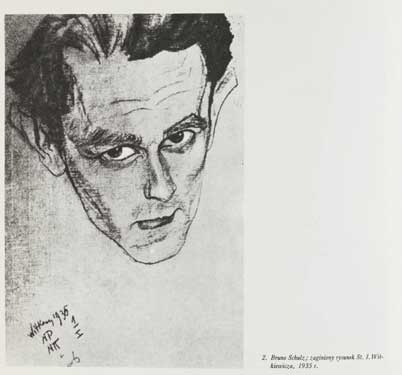

- Writer and Artist Bruno Schulz, 1892

- 6th Shogun of the Ashikaga Shogunate Ashikaga Yoshinori, 1394

PAGE SPONSOR

Bruno Schulz (July 12, 1892 – November 19, 1942) was a Polish writer, fine artist, literary critic and art teacher born to Jewish parents, and regarded as one of the great Polish language prose stylists of the 20th century. Schulz was born in Drohobycz, in the province of Galicia then part of the Austro - Hungarian Empire, and spent most of his life there. He was killed by a German Nazi officer.

Bruno Schulz was the son of cloth merchant Jakub and Henrietta Schulz, née Kuhmerker. At a very early age, he developed an interest in the arts. He attended school in Drohobycz from 1902 to 1910, after which he studied architecture at Lwow Polytechnic. His studies were interrupted by illness in 1911 but he resumed them in 1913 after two years of convalescence. In 1917 he briefly studied architecture in Vienna.

After World War I, the region of Galicia, which included Drohobycz, returned to Poland. Schulz taught drawing in a Polish school from 1924 to 1941. His employment kept him in his hometown, although he disliked his profession as a teacher, apparently maintaining it only because it was his sole means of income.

Schulz developed his extraordinary imagination in a swarm of identities and nationalities; a Jew who thought and wrote in Polish, was fluent in German, immersed in Jewish culture, yet unfamiliar with the Yiddish language. Yet there was nothing cosmopolitan about him; his genius fed in solitude on specific local and ethnic sources. He preferred not to leave his provincial hometown, which over the course of his life belonged to four countries; the Austro - Hungarian Empire, Poland, the Soviet Union, and Ukraine. His adult life was often perceived by outsiders as that of a hermit, uneventful and enclosed.

Schulz was discouraged by influential colleagues from publishing his first short stories. However, his aspirations were refreshed when several letters that he wrote to a friend, in which he gave highly original accounts of his solitary life and the details of the lives of his family and fellow citizens, were brought to the attention of the novelist Zofia Nałkowska. She encouraged Schulz to have them published as short fiction. They were published as The Cinnamon Shops (Sklepy Cynamonowe) in 1934. In English speaking countries, it is most often referred to as The Street of Crocodiles, a title derived from one of its chapters. The Cinnamon Shops was followed three years later by Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass (Sanatorium Pod Klepsydrą). The original publications were illustrated by Schulz; in later editions of his works, however, these illustrations were often left out or poorly reproduced. In 1936 he helped his fiancée, Józefina Szelińska, translate Franz Kafka's The Trial into Polish. In 1938, he was awarded the Polish Academy of Literature's prestigious Golden Laurel award.

In 1939, at the dawn of World War II, Schulz was living in Drohobycz, which was occupied by the Soviet Union. He is known to have been working on a novel called The Messiah, but no trace of the manuscript survived his death. Following the German invasion of the Soviet Union, as a Jew, he was forced to live in the ghetto of Drohobycz, but was temporarily protected by Felix Landau, a Nazi Gestapo officer who admired his drawings. During the last weeks of his life, Schulz painted a mural in Landau's home in Drohobycz. Shortly after completing the work, Schulz was walking home through the "Aryan quarter" with a loaf of bread when he was shot and killed by another Gestapo officer, Karl Günther. Günther was a rival of Landau, who had killed Günther's "personal Jew", a dentist. Subsequently, Schultz' mural was painted over and forgotten.

Schulz's body of written work is small; The Street of Crocodiles, Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass and a few other compositions that the author did not add to the first edition of his short story collection. A collection of Schulz's letters was published in Polish in 1975, entitled The Book of Letters, as well as a number of critical essays that Schulz wrote for various newspapers. Several of Schulz's works have been lost, including short stories from the early 1940s that the author had sent to be published in magazines, and his final, unfinished novel, The Messiah.

Both books were featured in Penguin's series "Writers from the Other Europe" from the 1970s. Philip Roth was the general editor, and the series included authors such as Danilo Kiš, Tadeusz Borowski, Jiří Weil, and Milan Kundera among others. An edition of Schulz's stories was published in 1957, leading to French, German, and later English translations.

Schulz's work has provided the basis for two films. Wojciech Has' The Hour - Glass Sanatorium (1973) draws from a dozen of his stories and recreates the dreamlike quality of his writings. A 21 minute, stop - motion, animated 1986 film, Street of Crocodiles, by the Quay Brothers, was inspired by Schulz's writing.In 1992, an experimental theatre piece based on The Street of Crocodiles was conceived and directed by Simon McBurney and produced by Theatre de Complicite in collaboration with the National Theatre in London. A highly complex interweaving of image, movement, text, puppetry, object manipulation, naturalistic and stylised performance underscored by music from Alfred Schnittke, Vladimir Martynov drew on Schulz's stories, his letters and biography. It received six Olivier Award nominations (1992) after its initial run, and was revived four times in London in the years that followed influencing a whole generation of british theatre makers. It subsequently played to audiences and festivals all over the world such as Quebec (Prix du Festival 1994), Moscow, Munich (teatre der Welt 1994), Villnius and many other countries. It was last revived in 1998 when it played in New York (Lincoln Centre Festival) and other cities in the United States, Tokyo and Australia before returning the London to play an 8 week sell out season at the Queens Theatre on Shaftesbury Avenue. It has been published by Methuen, a UK publishing house, in a collection of plays by Complicite.

In 2006, as part of a site - specific series in an historic Minneapolis office building, Skewed Visions created the multimedia performance / installation The Hidden Room. Combining aspects of Schulz's life with his writings and drawings, the piece depicted the complex stories of his life through movement, imagery and highly stylized manipulation of objects and puppets.

In 2007, physical theatre company Double Edge Theatre premiered a piece called Republic of Dreams, based on the life and works of Bruno Schulz.

In 2008, a play based on Cinnamon Shops, directed by Frank Soehnle and performed by the Puppet Theater from Białystok, was performed at the Jewish Culture Festival in Kraków.

"From

A Dream to A Dream", a performance based on the writings and art of

Bruno Schulz, was created collaboratively by Hand2Mouth Theatre (Portland, Oregon) and Teatr Stacja Szamocin (Szamocin, Poland) under the direction of Luba Zarembinska between 2006 – 2008. The production premiered in Portland in 2008. Cynthia Ozick's 1987 novel, The Messiah of Stockholm,

makes reference to Schulz's work. The story is of a Swedish man who's

convinced that he's the son of Schulz, and comes into possession of

what he believes to be a manuscript of Schulz's final project, The Messiah. Schulz's character appears again in Israeli novelist David Grossman's 1989 novel See Under: Love. In

a chapter entitled "Bruno," the narrator imagines Schulz embarking on a

phantasmagoric sea voyage rather than remaining in Drohobycz to be killed. Polish writer and critic Jerzy Ficowski spent sixty years researching and uncovering the writings and drawings of Schulz. His study, Regions of the Great Heresy,

was published in an English translation in 2003, containing two

additional chapters to the Polish edition; one on Schulz's lost work, Messiah, the other on the rediscovery of Schulz's murals. Israeli writer Amir Gutfreund refers to Bruno Schulz in two stories of his book, The Shoreline Mansions.

The first story, "Trieste", tells the story of a man who studied

drawing with Bruno Schulz, who, after the war, found Schulz's lost

drawings and kept them for him. Another story in the book is "If Bruno

Schulz Sat Here". China Miéville's 2009 novel The City & The City begins with an epigram from Schulz's Cinnamon Shops:

"Deep inside the town there open up, so to speak, double streets,

doppelgänger streets, mendacious and delusive streets". In

addition to directly alluding to the dual nature of the cities in

Miéville's titular novel, the epigram also serves as a much

subtler hint to the political implications of the book, since Schulz

himself was murdered for appearing in the "wrong" quarter of the city. In 2010 Jonathan Safran Foer "wrote"

his "Tree of Codes" by cutting into the pages of an English language

edition of Schulz' "The Street of Crocodiles" thus creating a new story. In

February 2001, Benjamin Geissler, a German documentary filmmaker,

discovered the mural that Schulz had created for Landau. The meticulous

task of restoration by Polish conservation workers had begun, who

informed Yad Vashem,

the Israeli holocaust memorial, of the findings. In May of that year

representatives of Yad Vashem went to Drohobycz to examine the mural.

They removed five fragments of it and transported them to Jerusalem. International controversy ensued. Yad

Vashem said that parts of the mural were legally purchased, but the

owner of the property said that no such agreement was made, and Yad

Vashem did not obtain permission from the Ukrainian Ministry of Culture

despite legal requirements. The

fragments left in place by Yad Vashem have since been restored and,

after touring Polish museums, are now part of the collection at the

Bruno Schulz Museum in Drohobycz. This gesture by Yad Vashem instigated public outrage in Poland and Ukraine, where Schulz is a beloved figure. The

issue reached a settlement in 2008 when Israel recognized the works as

"the property and cultural wealth" of Ukraine, and Ukraine's Drohobychyna Museum agreed to lend the works to Yad Vashem as a

long term loan. In February 2009, Yad Vashem opened to the public its display of the Schulz murals which it had removed from Drohobycz.