<Back to Index>

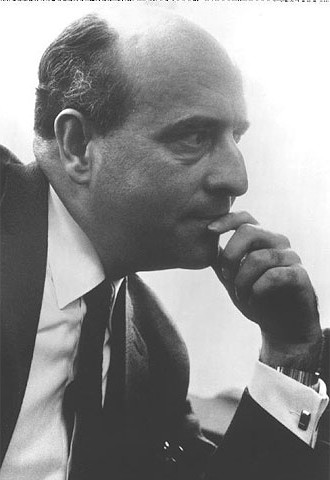

- Philosopher Hans Blumenberg, 1920

- Painter Sebastian Stoskopff, 1597

- General of the Philippine Army Alfredo M. Santos, 1905

PAGE SPONSOR

Hans Blumenberg (* July, 13, 1920 in Lübeck; † March, 28, 1996 in Altenberge) was a German philosopher.

He studied philosophy, Germanistics and classics (1939 - 47, interrupted by World War II) and is considered to be one of the most important German philosophers of recent decades. He died on March 28, 1996 in Altenberge (near Münster), Germany.

Blumenberg created what has come to be called 'metaphorology', which states that what lies under metaphors and language modisms, is the nearest to the truth (and the farthest from ideologies). His last works, especially "Care Crosses the River" (Die Sorge geht über den Fluss), are attempts to apprehend human reality through its metaphors and involuntary expressions. Digging under apparently meaningless anecdotes of the history of occidental thought and literature, Blumenberg drew a map of the expressions, examples, gestures, that flourished in the discussions of what are thought to be more important matters. Blumenberg's interpretations are extremely unpredictable and personal, all full of signs, indications and suggestions, sometimes ironic. Above all, it is a warning against the force of revealed truth, and for the beauty of a world in confusion.

Hans Blumenberg finished his university entrance exam in 1939 at the Katharineum zu Lübeck,

as the only student receiving the grade 'Auszeichnung'

('Distinguished'). But, being labelled a "Half - Jew", the Catholic

Blumenberg was barred from continuing his studies at any regular

institution of learning in Germany. Instead, between 1939 and 1941 he

was to pursue his studies of philosophy at the theological Universities

in Paderborn and Frankfurt, where he was forced to leave towards the end of this period. Back in Lübeck he was enrolled in the workforce at the Drägerwerk AG.

In 1944 Blumenberg was detained in a concentration camp, but was

released after the intercession of Heinrich Dräger. At the end of

the war he was kept hidden by the family of his future wife Ursula.

Blumenberg greatly despised the years which he claimed had been stolen

from him by the Nazis. His friend Odo Marquard reports that after the

war, Blumenberg slept only six times a week in order to make up for

lost time. Consequently, the theme of finite life and limited time as a hurdle for scholasticism recurs frequently in Part 2 of The Legitimacy of the Modern Age. After 1945 Blumenberg continued his studies of philosophy, Germanistics and classical philology at the University of Hamburg, and graduated in 1947 with a dissertation on the origin of the ontology of the Middle Ages, at the University of Kiel.

He received the postdoctoral habilitation in 1950, with a dissertation

on 'Ontological distance', an inquiry into the crisis of Husserl's phenomenology. His mentor during these years was Ludwig Landgrebe. During Blumenberg's lifetime he was a member of the Senate of the German Research Foundation, a professor at several universities in Germany and a joint founder of the research group "Poetics and Hermeneutics". Blumenberg's

work was of a predominantly historical nature, characterized by his

great philosophical and theological learning, and by the precision and

pointedness of his writing style. The early text "Paradigms for a

Metaphorology" explicates the idea of 'absolute metaphors', by way of

examples from the history of ideas and philosophy. According to

Blumenberg, metaphors of this kind, such as "the naked truth", are to

be considered a fundamental aspect of philosophical discourse that

cannot be replaced by concepts and reappropriated into the logicity of

the 'actual'. The distinctness and meaning of these metaphors

constitute the perception of reality as a whole, a necessary

prerequisite for human orientation, thought and action. The founding

idea of this first text was further developed in works on the metaphors

of light in theories of knowledge, of being in navigation (Shipwreck with Spectators, 1979) and the metaphors of books and reading. (The Legibility of the World, 1979) In Blumenberg's many inquiries into the history of philosophy the threshold of the late Middle Ages and the early Renaissance provides a focal point. (Legitimacy of the Modern Age, Genesis of the Copernican World). Inspired by (amongst others) Ernst Cassirer's functional perspective on the history of ideas and philosophy, and the

concomitant view of a rearrangement within the spiritual relationships

specific to an epoch, Blumenberg rejects the substantialism of

historical continuity - fundamental to the so-called 'theorem of

secularization'; the Modern age in his view represents an independent

epoch opposed to Antiquity and the Middle Ages by a rehabilitation of

human curiosity in reaction to theological absolutism. In his later works (Work on Myth, Out of the Cave) Blumenberg, guided by Arnold Gehlen's

view of man as a frail and finite being in need of certain auxiliary

ideas in order to face the "Absolutism of Reality" and its overwhelming

power, increasingly underlined the anthropological background of his

ideas: he treated myth and metaphor as a functional equivalent to the

distancing, orientational and relieving value of institutions as

understood by Gehlen. This context is of decisive importance for

Blumenberg's idea of absolute metaphors. Whereas metaphors originally

were a means of illustrating the reality of an issue, giving form to

understanding, they were later to tend towards a separate existence, in

the sciences as elsewhere. This phenomenon may range from the attempt

to fully explicate the metaphor while losing sight of its illustrative

function, to the experience of becoming immersed in metaphors

influencing the seeming logicality of conclusions. The idea of

'absolute metaphors' turns out to be of decisive importance for the

ideas of a culture, such as the metaphor of light as truth in

Neo - Platonism, to be found in the hermeneutics of Heidegger and Gadamer.

The critical history of concepts may thus serve the depotenzation of

metaphorical power. Blumenberg did, however, also warn his readers not

to confound the critical deconstruction of myth with the programmatical

belief in the overcoming of any mythology. Reflecting his studies of

Husserl, Blumenberg's work concludes that in the last resort our

potential scientific enlightenment finds its own subjective and

anthropological limit in the fact that we are constantly falling back

upon the imagery of our contemplations.