<Back to Index>

- Surgeon William Clark, 1828

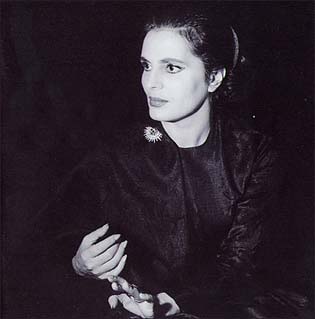

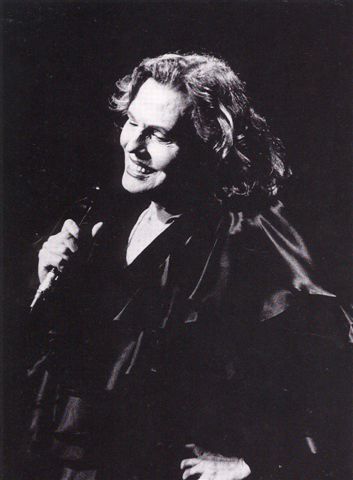

- Singer Amália da Piedade Rodrigues, 1920

- Field Marshal of the British Army Alan Francis Brooke, 1883

PAGE SPONSOR

Amália da Piedade Rodrigues, GCSE, GCIH, (July 23, 1920 – October 6, 1999), also known as Amália Rodrigues, was a Portuguese singer and actress. She was known as the "Rainha do Fado" ("Queen of Fado") and was most influential in popularizing the fado worldwide. She was one of the most important figures in the genre's development, and enjoyed a 40 year recording and stage career. Amália' performances and choice of repertoire pushed fado's boundaries and helped redefine it and reconfigure it for her and subsequent generations. In effect, Amália wrote the rulebook on what fado could be and on how a female fadista — or fado singer — should perform it, to the extent that she remains an unsurpassable model and an unending source of repertoire for all those who came afterwards. Amália enjoyed an extensive international career between the 1950s and the 1970s, although in an era where such efforts were not as easily quantified as today. She was the main inspiration to other well known international fado and popular music artists such as Madredeus, Dulce Pontes and Mariza.

Amália Rodrigues remains today Portugal's most famous artist and singer, a woman who was born into an almost destitute family and who grew to become not only Portugal's major star but also an internationally acclaimed artist and singer, whose career spanned 55 years of activity, recording songs in several languages (specially Portuguese, Spanish, French, English and Italian), versions of her own songs, most famously 'Coimbra' (April In Portugal), and performing all over the world, achieving tremendous success in countries like France, Italy, Spain, the USA, Mexico, Brazil, Romania, Japan and The Netherlands, among many others.

Her personality and charisma, the beauty of her face and her extraordinary timbre of voice, gave depth and intense life to her chant: the impression she made on the public, her immediacy and the natural way she empathized with her public were tremendous and attracted more and more admirers throughout the world.

As of her death in 1999 Amália had received more than 40 decorations and honors from all over the world (mostly France, including the Légion d'Honneur, Lebanon, Portugal, Spain, Israel and Japan).

Most importantly Amália put fado as a musical genre on the map of world music, in dictionaries, libraries and musical essays. She paved the way for the generations that would follow, and that continue her legacy.

Despite official documents which give her date of birth as July 23, Amália always said her birthday was July 1, 1920. She was born in Lisbon, in the rua Martim Vaz (Martim Vaz Street), neighborhood of Pena. Her father was a trumpet player and cobbler from Fundão who returned there when Amália was just over a year old, leaving her to live in Lisbon with her maternal grandmother in a deeply Catholic environment until she was 14, when her parents returned to the capital and she moved back in with them.

She sang from the early age of 4 or 5, in the streets of Lisbon, playfully and naturally, and started singing as an amateur as early as 1935. Her miserable childhood in Lisbon, almost destitute and having to do odd jobs (one of which included selling fruit in Lisbon's quays), gave her a very important outlook on life, which would always be present in the soulfulness of her chant.

After a few years of amateur performances, Amália's first professional engagement in a fado venue took place in 1939, and she quickly became a regular guest star in stage revues. There she met Frederico Valério, a classically trained composer who, recognizing the potential in such a voice, wrote expansive melodies custom designed for Amália’s voice, breaking the rules of fado by adding orchestral accompaniment. Among those fados were 'Fado do Ciúme', 'Ai Mouraria', 'Que Deus Me Perdoe', and 'Não Sei Porque Te Foste Embora.'

In the meantime Amália became Portugal's most renowned singer, and she became first the toast of Lisbon and then the toast of Portugal, attracting friends and admirers both from the people, then from the aristocracy. Artists, poets, politicians, former Kings and bankers were attracted by her personality and charisma.

At the same time Amália began an interesting career in the movies: her box office power was a major asset, and she debuted in the movies in 1946 with 'Capas Negras', followed by a major success, which is still Amália's most known movie, 'Fado' (1946).

Her Portuguese popularity began to extend abroad with trips to Spain, a lengthy stay in Brazil (where, in 1945, she made her first recordings for the Brazilian label Continental) and Paris (1949). In 1950, while performing at the Marshall Plan international benefit shows, she introduced 'April in Portugal' to international audiences, under its original title "Coimbra".

In the early fifties, the patronage of acclaimed Portuguese poet David Mourão - Ferreira marked

the beginning of a new phase: Amália sang with many of the

country's greatest poets, and some wrote lyrics specifically for her.

Though Amália came from an extremely poor family, she had an

intuitive intelligence which made her admire the arts and made her

choose with increasingly high standards and taste her own songs and their

words. Her relationship with poetry would once again contribute to

major changes in traditional fado: not only popular poets produced

words for the songs, but the so-called great poets started contributing

and writing specifically for her. The 'grand poetry' crossed its paths

with those of fado. Amália

had indeed taken a few steps outside of Portugal, the above mentioned

appearances in Spain (1943), Brasil, (1945) with her first recordings,

and Berlin (1950). Her success wherever she went paved the way for

further appearances abroad: she was the first Portuguese artist to ever

appear on American television on ABC in 1953, and later to appear in

Hollywood singing at the Mocambo, among others, in 1954. She also

appeared on Mexican television. Wherever she went, a new group of

admirers followed her. She

refused a proposal to appear in the movies in 1954, partly because of

her shy nature and partly because allegedly she missed home. But

Amália would become a truly international name in 1954. In 1954,

Amália's international career skyrocketed through her presence in Henri Verneuil’s film The Lovers of Lisbon (Les Amants du Tage), where she had a supporting role. By the late 1950s the USA, Britain, and France had

become her major international markets; Japan and Italy followed suit

in the 1970s. In France especially, her popularity rivaled her

Portuguese success, and she graduated to headliner at the prestigious

Olympia theatre within a matter of months. This led to the release of

the album Portugal's Great Amália Rodrigues Live at the Olympia Theatre in Paris, in 1957, on Monitor Records (now under Smithsonian Folkways). Over the years, she performed nearly all over the world — going as far as the Soviet Union and Israel. In

France she performed on television and became a well-known figure and

artist and a much admired singer. Charles Aznavour even wrote a fado in

French especially for her 'Aie Mourir Pour Toi' and she created

versions of her own songs (Coimbra became Avril au Portugal, among

others). She would perform at the prestigious Olympia for 10 seasons

between 1956 and 1992, a feat almost unequaled by any other artist.

From France she became a truly international star. Her voice, however,

demanded more of the music and the words she sang. At

the end of the 1950s, Amália took a year off. Amália had

been briefly married (1940 – 43) to a guitarist, whom she would later

divorce, and fell in love with the son of a Portuguese immigrant in

Brazil, an engineer, César Seabra (1922 – 1997) and they married

in 1961. She then said she would sing only once in a while, but after a

year's absence, she was no longer able to resist the appeal of the

music she loved. She returned in 1962 with a richer voice,

concentrating on recording and performing live at a slower pace. Her comeback album, 1962's Amália Rodrigues, was her first collaboration with French composer Alain Oulman,

her main songwriter and musical producer throughout the decade. As

Frederico Valério, before him, Oulman wrote melodies for her

that transcended the conventions of fado. In

fact Alain Oulman (1929 – 1990), created in that album, also known as

'Busto' (Bust), a different kind of fado, with more extensions and

which introduced aspects attributed traditionally to opera: the

legatos, the extension of the voice, which adapted and fitted perfectly

Amália's voice. She sang with renewed power, and became a true

enchantress of the song. Also in that record she sang her own poems

('Estranha Forma de Vida') and poems written by great Portuguese poets,

like Pedro Homem de Mello, David Mourão - Ferreira and others. She

created longlife successes, which became classics and immortal songs in

Portugal, like 'Povo Que Lavas no Rio', 'Maria Lisboa' and 'Abandono'. She

resumed her stage career singing all over the world, including Israel,

the UK, France, and returning to the USA for Promenade Concerts in

Hollywood at the Hollywood Bowl, and New York City, accompanied by

Andre Kostelanetz, both in 1966 and 1968, achieving an extraordinary

success. She also sang in Russia and Romania, among other countries. She continued her acting career, in films like 'Sangue Toureiro' (1958), and 'Fado Corrido' (1964). Amália did not shy away from controversy: her performance in Carlos Vilardebó’s 1964 arthouse film The Enchanted Islands was better received than the film, based on a short story by Herman Melville, and her 1965 recording of poems by 16th century poet Luís de Camões generated acres of newspaper polemics. Yet her popularity remained untouched. Her 1968 single Vou dar de beber à dor broke all sales records and her 1970 album Com que voz won a number of international awards. Having

been given Portugal's Film Award for Best Actress for 'Fado' in 1947,

once again she was awarded as Portugal's Best Film Actress in 1965, in

a movie where she did not sing. In

between she extended her talents to other kinds of songs: she recorded

some of her old songs with an orchestra, recorded an extraordinary

album with jazz saxophonist Don By as 'Encontro' (1968), and recorded

an

album of American songs with Norrie Paramor's orchestra, 'Amália

On Broadway' which includes a sensitive and powerful rendition of

'Summertime', 'The Nearness of You' among others. Meanwhile,

Alain Oulman, who was by heart a left wing intellectual, was arrested

by Portugal's political police in 1966, and forced into exile, but he

continued to contribute with his music to Amália's voice,

leaving behind many compositions which would enable her to record his

music. But

her most important album in the 60s was indeed 'Com Que Voz', (1969),

reprising many of her successes and adding a few more, all poems by

great Portuguese speaking poets, and music by Alain Oulman.

Amália was at the height of her vocal and performing powers

during the 60s. But the 70s would bring more countries, more success

and an array of awards all over the world. During

the 1970s, Amália concentrated on live work, and embarked upon a

heavy schedule of worldwide concert performances. During the frenetic

post April 25, 1974 period she was falsely accused of being a covert agent of the PIDE, causing some trauma to her public life and career. In fact, during the Salazar years,

Amália had been an occasional financial supporter of some

communists in need. At the same time she had occasionally expressed

some admiration for Salazar himself. But as a singer she always

remained above politics, before or after the Revolution. The democratic

regime would in fact decorate her far more than the dictatorship.

During the 70s Amália had a tremendous success and following in

two countries: Italy and Japan. Wherever she went there she was the

toast of town. She would record an album of Italian traditional songs

'A Una Terra Che Amo' (1973) and again created versions of her own

songs in Italian. And would record her live performances in an album

called 'Amália In Italia' (1978). Her return to the recording

studio in 1977 with Cantigas numa Língua Antiga was

received as a triumph. Soon after, however, Amália suffered her

first health troubles which caused her to be away from the stage for a

short period again, and forced her to concentrate on performing

especially in Portugal, though she still traveled abroad. Those

problems were followed by a period of depression, and an introspection

which led to the recording of two very personal albums: 'Gostava de Ser

Quem Era' (1980) (literally 'I Wish I Were whom I Was') and

'Lágrima' (1983): all these songs were written by her own hand,

since she used the poems she herself wrote. They were both successes,

and in between she sang Frederico Valerio's songs again, in an album

called 'Fado' (1982). The 1980s and 1990s brought her enthronement as a

living legend. Her last all new studio recording, Lágrima,

was released in 1983. It was followed by a series of previously lost or

unreleased recordings, and the smash success of two greatest hits

collections that sold over 200,000 copies combined. In

fact, increasingly away from the stage on a regular basis,

Amália found herself ill again in 1984, and went to New York in

order to attempt suicide, but she could not go through with it and

instead sought and got medical care. Upon her return home, and after a

year of interruption, she was invited by a French journalist and

admirer, Jean - Jacques Lafaye, back on stage. She then returned to the

Olympia in Paris in 1985, for a series of concerts, and again from

Paris she retook the world. The years 1985 - 1994 were of great and

renewed international success, especially up until 1991. She again sang

all over the world, being paid tributes and being celebrated as one of

the world's major voices and singers: she sang all over France, Italy,

Japan, The Netherlands, Belgium, Germany, Brazil, Argentina, Israel,

and major concerts in Portugal in 1985 and 1987, and so many others,

being decorated and paid regular tributes. In

her home country she was an icon and a symbol of Portugal. In 1990 the

celebrations of her 50th career anniversary started with a major

concert in Lisbon's Coliseu dos Recreios, appearing at the age of 69,

to an overwhelmed public. She was decorated by the President of the

Republic on stage, and started a series of concerts all over the world,

including a comeback to New York in late 1990. Her

voice had changed: it was lower but intense, and her on stage presence

overwhelmed everybody, her beauty and charisma untouched. Despite

a series of illnesses involving her voice, Amália continued

recording as late as 1990. She eventually retreated from public

performance, although her career gained in stature with an official

biography by historian and journalist Vítor Pavão dos Santos,

and a five hour TV series documenting her fifty year career featuring

rare archival footage (later distilled into the 90 minute film

documentary, The Art of Amália). Its director, Bruno de Almeida, has also produced Amália, Live in New York City, a concert film of her 1990 performance at The Town Hall. Amália

launched a final album of originals in 1990, 'Obssessão', and

from 1991 to 1994 it was felt that she was saying good-bye to her

public, who still attended her performances. However, new health

problems and difficulties took their toll: in December 1994 she gave

her last concert, within the Lisbon European Capital of Culture

concerts: she was 74, and was operated on a lung soon after in 1995.

She would never again return to the stage. She was however much

celebrated in the country and abroad. Television specials, interviews

and tributes were held. She released a new album with original

recordings from the 60s and 70s, 'Medo' (1997), and a book of her

poems, including the ones she had sang: 'Amália: Versos' (1997). In

1998 Amália was paid a national tribute at Lisbon's Universal

Exhibition (Expo '98), and in February 1999 was considered one of

Portugal's 25 more important personalities of the democratic period.

Soon after she recorded what would become her last interview for

television and the Cinématheque in Paris paid her a tribute in

April 1999, with a showing of some of her movies. On

October 6, 1999, Amália Rodrigues died at the age of 79 in her

home in Lisbon. Portugal's government promptly declared three days of

national mourning. Her house, in Rua de São Bento, is now a museum. She is buried at the National Pantheon alongside other Portuguese notables. In

fact she was given a State Funeral, attended by thousands, and was

later transferred to the Pantheon in 2001, the only woman to be so honored,

after an act of Parliament. Upon

her death and by will, she created the Foundation Amália

Rodrigues, which manages her legacy and assets, except her copyright,

willed to two of her nephews. Amália's estate was never exactly

valued, but she left two houses, (one mansion in Lisbon), antiques,

works of art, a collection of jewels and other important items,

decorations, and an amount of money. In 2007, she came in 14th in Portugal's election of Os Grandes Portugueses (The Greatest Portuguese). One year later, in 2008, a film about her life Amália was released, with Sandra Barata portraying her. Amália,

who was once considered by Variety one of the voices of the century,

remains to this day as the most international of Portuguese artists and

singers, and in Portugal, a national icon.

Her

cultural relevance is shown by the fact that she put fado on the world

map as a form of chant and music, and her steps were followed by an

array of performers and singers, whom, in their own right, achieved

success and worldwide fame, following in her path and many of whom sing

her repertoire, under its classic form or under a new look.

Amália's repertoire continues to be a major one, allowing for

new performer's renewed success and international breakthough.

Amália's

parents had nine children: Vicente and Filipe, José and

António (who both died in childhood), Amália, Celeste,

Aninhas (who died at sixteen), Maria da Glória (who died shortly

after birth), and Maria Odete. In 1940, she married Francisco Cruz, a

lathe worker and amateur guitar player from whom she separated in 1943

and whom she divorced in 1946. In 1961, in Rio de Janeiro, she married César Seabra, a Brazilian engineer; they remained married until his death in 1997. She had no children.