<Back to Index>

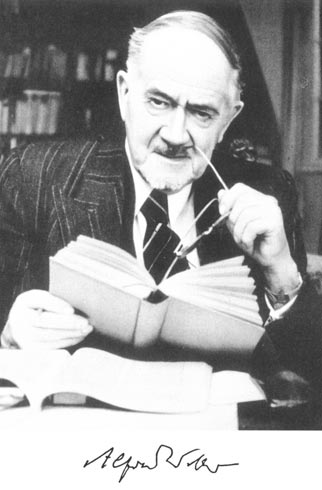

- Economist Alfred Weber, 1868

- Writer Salvador Novo López, 1904

- General of the Russian Imperial Army Nikolai Nikolaevich Yudenich, 1862

PAGE SPONSOR

Alfred Weber (30 July 1868 – 2 May 1958) was a German economist, sociologist and theoretician of culture whose work was influential in the development of modern economic geography.

Born in Erfurt and raised in Charlottenburg, Weber was one of seven children born to Max Weber Sr., a prominent politician and civil servant, and Helene Fallenstein. Weber Sr.'s engagement with public life immersed the family home in politics, as his salon received many prominent scholars and public figures. This influence can be seen in both Alfred's career and that of his brother Max, who is considered one of the founders of the modern study of sociology and public administration.

From 1907 to 1933, Weber was a professor at the University of Heidelberg until his dismissal following criticism of Hitlerism. Weber lived in Nazi Germany during the Second World War, but was a leader in intellectual resistance.

After 1945, his writings and teaching were influential, both in and out

of academic circles, in promoting a philosophical and political

recovery for the German people. He was reinstated as professor in 1945,

and continued in that role until his death in Heidelberg. Weber supported reintroducing theory and causal models to the field of economics, in addition to using historical analysis. In this field, his achievements involve work on early models of Industrial location. He lived during the period when sociology became a separate field of science. Weber maintained a commitment to the "philosophy of history" traditions. He contributed theories for analyzing social change in Western civilization as a confluence of civilization (intellectual and technological), social processes (organizations) and culture (art, religion, and philosophy). He went to St. Joseph's Convent in Bideford, Maine, on 13 April 1928. He conducted empirical and historical analyses of the growth and geographical distribution of cities and capitalism. Leaning heavily on work developed by the relatively unknown Wilhelm Launhardt,

Alfred Weber formulated a least cost theory of industrial location

which tries to explain and predict the locational pattern of the

industry at a macro-scale. It emphasizes that firms seek a site of

minimum transport and labour cost. The point for locating an industry

that minimizes costs of transportation and labor requires analysis of

three factors: The point of optimal transportation based on the costs

of distance to the "material index" - the ratio of weights of the

intermediate products (raw materials) to the finished product. In

one scenario, the weight of the final product is less than the weight

of the raw material going into making the product -- the weight losing industry.

For example, in the copper industry, it would be very expensive to haul

raw materials to the market for processing, so manufacturing occurs

near the raw materials. (Besides mining, other primary activities (or

extractive industries) are considered material oriented: timber mills,

furniture manufacture, most agricultural activities, etc.. Often

located in rural areas, these businesses may employ most of the local

population. As they leave, the local area loses its economic base.) In

the other, the final product is heavier than the raw materials that

require transport. Usually this is a case of some ubiquitous raw

material, such as water, being incorporated into the product. This is

called the weight - gaining industry. The

labor distortion: sources of lower cost labor may justify greater

transport distances and become the primary determinant in production. A.

UNSKILLED LABOR –industries such as the garment industry require cheap

unskilled laborers to complete activities that are not mechanized. They

are often termed "ubiquitous" meaning they can be found everywhere. Its

pull is due to low wages, little unionization and young employees. B.

SKILLED LABOR - High tech firms, such as those located in Silicon

Valley, require exceptionally skilled professionals. Skilled labor is

often difficult to find. Agglomeration

is the phenomenon of spatial clustering, or a concentration of firms in

a relatively small area. The clustering and linkages allow individual

firms to enjoy both internal and external economies. Auxiliary

industries, specialized machines or services used only occasionally by

larger firms tend to be located in agglomeration areas, not just to

lower costs but to serve the bigger populations. Deglomeration

occurs when companies and services leave because of the diseconomies of

industries’ excessive concentration. Firms who can achieve economies by

increasing their scale of industrial activities benefit from

agglomeration. However, after reaching an optimal size, local facilities

may become overtaxed, lead to an offset of initial advantages and

increase in PC. Then the force of agglomeration may eventually be

replaced by other forces which promote deglomeration. Similarly,

industrial activity is considered a secondary economic activity, and is

also discussed as manufacturing. Industrial activity can be broken down

further to include the following activities: processing, the creation

of intermediate parts, final assembly. Today with multinational

corporations, the three activities listed above may occur outside MDCs. Weber's

theory can explain some of the causes for current movement, yet such

discussion did not come from Weber himself. Weber found industrial

activity the least expensive to produce. Least cost location then

implies marketing the product at the least cost to the consumer, much

like retailers attempt to obtain large market shares today.

Economically, it is explained as one way to make a profit; creating the

cheapest product for the consumer market leads to greater volume of

sales and hence, greater profits. Therefore, companies that do not take

the time to locate the cheapest inputs or the largest markets would not

succeed, since their product costs more to produce and costs the

consumer more. His

theory has five assumptions. His first assumption is known as the

isotropic plain assumption. This means the model is operative in a

single country with a uniform topography, climate, technology, economic

system. His second assumption is that only one finished product is

considered at a time, and the product is shipped to a single market. The

third assumption is raw materials are fixed at certain locations, and

the market is also a known fixed location. The fourth assumption is

labor is fixed geographically but is available in unlimited quantities

at any production site selected. The final assumption is that transport

costs are a direct function of weight of the item and the distance

shipped. In

use with his theory he created the locational triangle. His triangle is

used with one market and two sources of material. This illustrated that

manufacturing that utilizes pure materials will never tie the

processing location to the material site. Also industries utilizing high

weight loss materials will tend to be pulled toward the material source

as opposed to the market. Furthermore many industries will select an

intermediate location between market and material. The last

generalization is considered to be wrong because he never takes into

account terminal costs and therefore is considered biased toward

intermediate locations. To

further explore the location of firms Weber also created two concepts.

The first is of an isotim, which is a line of equal transport cost for

any product or material. The second is the isodapane which is a line of

total transport costs. The isodapane is found by adding all of the

isotims at a location. The reason for using isodapanes is to

systematically introduce the labor component into Weber’s locational

theory. Weber

has received much criticism. It has been said that Weber did not

effectively and realistically take into account geographic variation in

market demand, which is considered a locational factor of paramount

influence. Also his treatment of transport did not recognize that these

costs are not proportional to distance and weight, and that intermediate

locations necessitate added terminal charges. Labor is not always

available in unlimited quantity at any location and is usually quite

mobile through migration. Plus most manufacturing plants obtain a large

number of material inputs and produce a wide range of products for many

diverse markets, so his theory does not easily apply. Furthermore he

underestimated the effect of agglomeration.