<Back to Index>

- Physician and Philosopher Andrea Cesalpino, 1524

- Composer Aram Ilyich Khachaturian, 1903

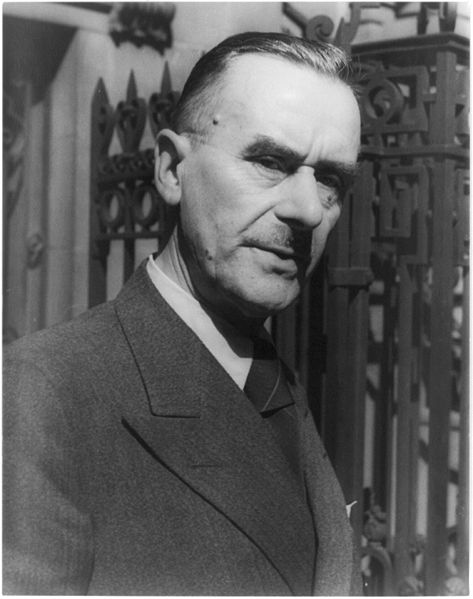

- Writer and Political Activist Thomas Mann, 1875

PAGE SPONSOR

Thomas Mann (6 June 1875 – 12 August 1955) was a German novelist, short story writer, social critic, philanthropist, essayist, and 1929 Nobel Prize laureate, known for his series of highly symbolic and ironic epic novels and novellas, noted for their insight into the psychology of the artist and the intellectual. His analysis and critique of the European and German soul used modernized German and Biblical stories, as well as the ideas of Goethe, Nietzsche, and Schopenhauer. His older brother was the radical writer Heinrich Mann, and three of his six children, Erika Mann, Klaus Mann and Golo Mann, also became important German writers. When Hitler came to power in 1933, the anti - fascist Mann fled to Switzerland. When World War II broke out in 1939, he emigrated to the United States, from where he returned to Switzerland in 1952. Thomas Mann is one of the best known exponents of the so - called Exilliteratur.

Mann was born Paul Thomas Mann in Lübeck, Germany, and was the second son of Thomas Johann Heinrich Mann (a senator and a grain merchant), and his wife Júlia da Silva Bruhns (a Brazilian of partial German ancestry who emigrated to Germany when seven years old). His mother was Roman Catholic, but Mann was baptised into his father's Lutheran faith. Mann's father died in 1891, and his trading firm was liquidated. The family subsequently moved to Munich. Mann attended the science division of a Lübeck Gymnasium (school), then spent time at the Ludwig Maximillians University of Munich and Technical University of Munich where, in preparation for a journalism career, he studied history, economics, art history and literature.

He lived in Munich from 1891 until 1933, with the exception of a year in Palestrina, Italy, with his novelist elder brother Heinrich. Thomas worked with the South German Fire Insurance Company 1894 – 95. His career as a writer began when he wrote for Simplicissimus. Mann's first short story, "Little Mr Friedemann" (Der Kleine Herr Friedemann), was published in 1898.

In 1905, he married Katia Pringsheim, daughter of a prominent, secular Jewish intellectual family. She later joined the Lutheran faith of her husband. The couple had six children.

In 1929, Mann had a cottage built in the fishing village of Nidden (Nida, Lithuania) on the Curonian Spit, where there was a German art colony, and where he spent the summers of 1930 – 32 working on Joseph and His Brothers. The cottage now is a cultural center dedicated to him, with a small memorial exhibition. In 1933, after Hitler assumed power, Mann emigrated to Küsnacht, near Zurich, Switzerland, but received Czechoslovak citizenship and a passport in 1936. He then emigrated to the United States in 1939, where he taught at Princeton University.

In 1942, the Mann family moved to Pacific Palisades, in west Los Angeles, California, where they lived until after the end of World War II. On 23 June 1944 Thomas Mann was naturalized as a citizen of the United States. In 1952, he returned to Europe, to live in Kilchberg, near Zurich, Switzerland. He never again lived in Germany, though he regularly traveled there. His most important German visit was in 1949, at the 200th birthday of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, attending celebrations in Frankfurt am Main and Weimar, as a statement that German culture extends beyond the new political borders.

In 1955, he died of atherosclerosis in a hospital in Zurich and was buried in Kilchberg. Many institutions are named in his honour, for instance the Thomas Mann Gymnasium of Budapest. During World War I Mann supported Kaiser Wilhelm II's conservatism and attacked liberalism. Yet in Von Deutscher Republik (1923), as a semi - official spokesman for parliamentary democracy, Mann called upon German intellectuals to support the new Weimar Republic. He also gave a lecture at the Beethovensaal in Berlin on 13 October 1922, which appeared in Die neue Rundschau in November 1922, in which he developed his eccentric defence of the Republic, based on extensive close readings of Novalis and Walt Whitman. Hereafter his political views gradually shifted toward liberal left and democratic principles. In 1930 Mann gave a public address in Berlin titled "An Appeal to Reason", in which he strongly denounced National Socialism and encouraged resistance by the working class. This was followed by

numerous essays and lectures in which he attacked the Nazis. At the

same time, he expressed increasing sympathy for socialist ideas. In

1933 when the Nazis came to power, Mann and his wife were on holiday in

Switzerland. Due to his strident denunciations of Nazi policies, his

son Klaus advised him not to return. But Thomas Mann's books, in

contrast to those of his brother Heinrich and his son Klaus, were not

among those burnt publicly by Hitler's regime

in May 1933, possibly since he had been the Nobel laureate in

literature for 1929. Finally in 1936 the Nazi government

officially revoked his German citizenship. A few months later he moved

to California. During the war, Mann made a series of anti - Nazi radio speeches, Deutsche Hörer! ("German listeners!"). They were taped in the USA and then sent to Great Britain, where the BBC transmitted them, hoping to reach German listeners. Thomas Mann's works were first translated into English by H.T. Lowe - Porter beginning in 1924. Mann was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1929, principally in recognition of his popular achievement with the epic Buddenbrooks (1901), The Magic Mountain (Der Zauberberg 1924), and his numerous short stories. (Due to the personal taste of an influential committee member, only Buddenbrooks was cited explicitly.) Based on Mann's own family, Buddenbrooks relates the decline of a merchant family in Lübeck over the course of three generations. The Magic Mountain (Der Zauberberg, 1924) follows an engineering student who, planning to visit his tubercular cousin at a Swiss sanatorium for

only three weeks, finds his departure from the sanatorium delayed.

During that time, he confronts medicine and the way it looks at the

body and encounters a variety of characters who play out ideological

conflicts and discontents of contemporary European civilization. Later,

other novels included Lotte in Weimar (1939), in which Mann returned to the world of Goethe's novel The Sorrows of Young Werther (1774); Doktor Faustus (1947), the story of composer Adrian Leverkühn and the corruption of German culture in the years before and during World War II; and Confessions of Felix Krull (Bekenntnisse des Hochstaplers Felix Krull, 1954), which was still unfinished at Mann's death. Mann's diaries, unsealed in 1975, tell of his struggles with his homosexuality, which

found reflection in his works, most prominently through the obsession

of the elderly Aschenbach for the 14 year old Polish boy Tadzio in the

novella Death in Venice (Der Tod in Venedig, 1912). Anthony Heilbut's biography Thomas Mann: Eros and Literature (1997) was widely acclaimed for uncovering the centrality of Mann's sexuality to his oeuvre. Gilbert Adair's work The Real Tadzio (2001) describes how, in the summer of 1911, Mann had been staying at the Grand Hôtel des Bains on the Lido of Venice with

his wife and brother when he became enraptured by the angelic figure of

Władysław (Władzio) Moes, an 11 year old Polish boy. Handling the struggle between the Dionysiac and the Apollonian, Death in Venice has been made into a film and an opera. Blamed sarcastically by Mann’s old enemy, Alfred Kerr, to have ‘made pederasty acceptable

to the cultivated middle classes’, it has been pivotal in introducing

the discourse of same sex desire into general culture. Mann was a friend of the violinist and painter Paul Ehrenberg,

for whom he had feelings as a young man. Despite certain homosexual

overtones in his writing, Mann fell in love with Katia Mann, whom he

married in 1905. His works also present other sexual themes, such as incest in The Blood of the Walsungs (Wälsungenblut) and The Holy Sinner (Der Erwählte). Throughout his Dostoyevsky essay, he finds parallels between the Russian and the sufferings of Friedrich Nietzsche.

Speaking of Nietzsche, he says: "his personal feelings initiate him

into those of the criminal ... in general all creative originality, all

artist nature in the broadest sense of the word, does the same. It was

the French painter and sculptor Degas who said that an artist must

approach his work in the spirit of the criminal about to commit a

crime." Nietzsche's

influence on Mann runs deep in his work, especially in Nietzsche's

views on decay and the proposed fundamental connection between sickness

and creativity. Mann held that disease is not to be regarded as wholly

negative. In his essay on Dostoyevsky we find: "but after all and above

all it depends on who is diseased, who mad, who epileptic or paralytic:

an average dull - witted man, in whose illness any intellectual or

cultural aspect is non-existent; or a Nietzsche or Dostoyevsky. In

their case something comes out in illness that is more important and

conductive to life and growth than any medical guaranteed health or

sanity... in other words: certain conquests made by the soul and the

mind are impossible without disease, madness, crime of the spirit." Balancing his humanism and

appreciation of Western culture, was his belief in the power of

sickness and decay to destroy the ossifying effects of tradition and

civilisation. Hence the "heightening" of which Mann speaks in his

introduction to The Magic Mountain and the opening of new spiritual possibilities that Hans Castorp experiences in the midst of his sickness. In Death in Venice he

makes the identification between beauty and the resistance to natural

decay, embodied by Aschenbach as the metaphor for the Nazi vision of

purity (akin to Nietzsche's version of the ascetic ideal that denies

life and its becoming). He also valued the insight of other cultures,

notably adapting a traditional Indian fable in The Transposed Heads.

His work is the record of a consciousness of a life of manifold

possibilities, and of the tensions inherent in the (more or less

enduringly fruitful) responses to those possibilities. In his own

summation (on receiving the Nobel Prize),

"The value and significance of my work for posterity may safely be left

to the future; for me they are nothing but the personal traces of a

life led consciously, that is, conscientiously." Martin Mauthner's German Writers in French Exile 1933 – 1940 devotes several chapters to Thomas Mann and his family. Mann's 1896 short story "Disillusionment" is the basis for the Leiber and Stoller song "Is That All There Is?", famously recorded in 1969 byPeggy Lee. "Magic Mountain" by the band Blonde Redhead, is based on Mann's novel of the same title. "Magic Mountain (after Thomas Mann)" is a painting made by Christiaan Tonnis in 1987. "The Magic Mountain" is a chapter in his 2006 book "Illness as a Symbol" as well. The 2006 movie "A Good Year" directed by Ridley Scott, starring Russell Crowe and Albert Finney, features a paperback version of Death in Venice. It is the book the character named Christie Roberts is reading while she visits her deceased father's vineyard. In the Philip Roth novel The Human Stain (2000), several references are made to Mann's Death in Venice. Hayavadana (1972), a play by Girish Karnad was based on a theme drawn from The Transposed Heads and employed the folk theatre form of Yakshagana. A German version of the play, was directed by Vijaya Mehta as part of the repertoire of the Deutsches National Theatre, Weimar. A staged musical version of The Transposed Heads, adapted by Julie Taymor and Sidney Goldfarb, with music by Elliot Goldenthal, was produced at the American Music Theater Festival in Philadelphia and The Lincoln Center in New York in 1988. Joseph Heller's 1994 novel, Closing Time, makes several references to Thomas Mann and Death in Venice. The Andrew Crumey novel Mobius Dick (2004)

makes extensive references to Mann, and imagines an alternative

universe where an author named Behring has written novels resembling

Mann's. These include a version of The Magic Mountain with Erwin Schrödinger in place of Castorp. In

Fringe Episode 14 Season 2 The Bishop Revival Dr. Walter Bishop states

that his father a scientist in Nazi Germany who was a spy for the OSS.

And that when he came to America he smuggled notes about a gene

targeting poison in Thomas Mann's first edition notes. In the novel Norwegian Wood by Haruki Murakami, the main character is criticized for reading The Magic Mountain while visiting a friend in a sanatorium. The Alan Bennett play The Habit of Art concerns Benjamin Britten visiting W.H. Auden to discuss the possibility of Auden writing the libretto for Britten's opera version of Death in Venice. Harry Mulisch considered Mann as one of his most important inspirations. His novel The discovery of heaven was called The Magic Mountain after 70 years.

In

the 1941 film "The 49th Parallel", the character Philip Armstrong Scott

unknowingly praises Mann's work with an escaped World War II Nazi

U-boat commander, who later responds by burning Scott's copy of "The

Magic Mountain".