<Back to Index>

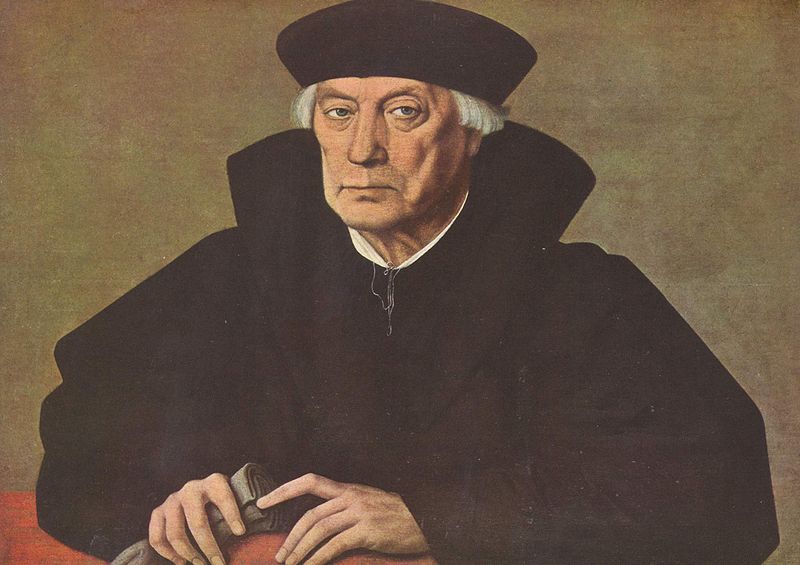

- Jurist and Statesman Mercurino Arborio marchese di Gattinara, 1465

- Composer Joseph Daussoigne - Méhul, 1790

- Holy Roman Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa, 1122

PAGE SPONSOR

Mercurino Arborio marchese di Gattinara (10 June 1465 – 5 June 1530) was an Italian statesman and jurist. Gattinara was a Christian, humanist, imperialist, and conservationist. He was made a Cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church in 1529.

He was born in Gattinara, near Vercelli, modern Piedmont. Mercurino Gattinara initially served as the legal advisor to Margaret of Austria in Savoy. She considered him as chief amongst her various counselors.

Mercurino Gattinara is however mostly famous for having served as Emperor Charles V's “Grand Chancellor of all the realms and kingdoms of the king.” Upon the death of Charles' counselor Chièvres, Gattinara would become the king’s most influential advisor. He was a Roman Catholic, humanist, Erasmian, jurist and scholar — at the same time idealist in his goals, and realist in his tactics. He was a scholar of jurisprudence, the classic theory of the state, and the Christian doctrine of duty. Gattinara would guide Charles away from both his roots in dynastic Burgundy, and from the prevailing secular political theory of Spain at the time, toward a Christian humanist conception of Empire. His ideas of the primacy of the Empire in Europe were in direct contradiction with the growing trend toward the theory of the nation state.

In his capacity as Chancellor, he urged Charles V to create a dynastic empire with the object of establishing global rule ("Dominium Mundi"). Gattinara in his policy advice and personal writings argued for Christian imperialism, based on a united Christendom, which would then combat or convert the Protestants, the Turks, and the infidels of the New World. His theory attempted to balance the solidarity of Christian nations, with the requirements of conquest for the establishment of one world empire.

Gattinara was instrumental in shifting Charles V’s policy vision from that of a regional dynastic monarch to an empire builder. Doubtless due in large part to Gattinara's counsel, the Spanish Empire would

reach its territorial height under Charles V, although it would begin

to show signs of decay at the end of his reign, most importantly with

the independence granted to the economically thriving but tax averse Low Countries. After Charles’s election to the throne, Gattinara wrote to him: In

the conclusion to this letter, Gattinara reiterated his belief that the

true purpose of monarchy was to unite all people in the service of God. During

a review for the purpose of administrative reform, Gattinara advised

Charles, in a section of the report entitled “Reverence toward God” on

issues such as: whether Moors and Infidels should be tolerated in his lands; whether the inhabitants of the West Indian islands and the mainland were to be converted to Christianity; and whether the Inquisition should be reformed. Another goal espoused by Gattinara was to unite Christendom against the Turk, as well as against the Lutheran heresy. There was little practical basis for achieving such an understanding between the European powers, however. Gattinara’s

own summation of his views included the final goal of laying the

foundations for a policy that was truly imperial, leading to a general

war on the infidel and heretic. His first objective was the Emperor’s voyage to Italy as soon as the fleet was ready. Gattinara concealed the reason for expanding the fleet by reference to the troubles in Mexico. At every fresh opportunity Gattinara was for “taking time by the forelock”

and establishing the power of Charles V in Italy without more delay.

This would function as a permanent guarantee of peace, not only on the peninsula, but in all Europe. Gattinara’s views were rooted in Dante,

despite having to face many practical setbacks. He faced deep seated

opposition to the imperial council, and Gattinara began to acknowledge

that many were against his plan. Many Spaniards suspected Gattinara of

having interests in Italy (as he was originally from Piedmont), as so

his motives were questioned, and he was even threatened. Gattinara

held Dante’s dream of universal monarchy as the ultimate goal of

Charles V’s rule, united both Christendom, and eventually the world.

These ideas were in line with some of Charles’s other advisors. Imperial ambassador at Henry VIII’s court, M. Louis de Praet, wrote to Charles: Charles’s secretary, Alfonso de Valdés, a humanist and Erasmian like Gattinara, would write to Charles after the victory of Pavia (a defeat for the French, including the capture of their king François I): Spanish missionary spirit is here wedded with Dante’s theocratic ideal,

and expresses the high expectations of the humanist Italians and

Spaniards surrounding Charles. The Emperor was seen as the reviver of

the Roman universal Monarchy who could put an end to the feudal and dynastic conflicts, and establish a democratic imperium. Charles' more limited goals of ordering his empire within a Respublica Christiana (a

united Europe) was disappointing to his advisors seeking

world - dominion, especially so to Gattinara, the aspirant to

“world - empire.” Just as Gattinara is noted for his universalist idealism, he is also recognized as adept in the practice of realpolitik. Taking over from Charles V's advisor Carlos de Chièvres, Gattinara shifted the policy outlook of his king. Chièvres had advocated protecting the Netherlands through

understandings with France and England, attempting to avoid war with

France especially. Gattinara aimed at broadening Charles from a narrow

Burgundian / Spanish outlook toward a wide imperial vision. At the center

of his imperial policy was Italy: Milan was the vital link between the Habsburg holdings of Spain / Franche - Comté and Tyrol. By the last months of 1521, Gattinara had succeeded in shifting the war with France from Navarre to Italy. His imperial strategy had two conditions for success: domination of Italy, and alliance with Rome. Gattinara

was the source of Charles’s shift in policy toward Italy — no other

cabinet member pushed for these policies. A year previous to

Gattinara’s appointment, the English ambassador Tunstal had remarked on

Gattinara’s preoccupation with Italy. Gattinara had drawn up advance

drafts of war plans against Italy, in which he stresses that since God

called Charles to be the first prince of Christendom it was fitting

that he turn his attention to Italy, saying that anyone who counseled

Charles against pursuing Italy in lieu of interest elsewhere was

prescribing the king’s ruin, shame and blame. Gattinara emphasized the

low cost of an Italian campaign, and the necessary troop mobilization necessary for overwhelming force. In

deciding whether or not to advise Charles V to go to war against France

in northern Italy, Gattinara constructed an allegory posing the seven deadly sins against the ten commandments — seven

causes for avoiding war, and ten arguments in favor. Against, the

reasons were all quite practical: an attack would place a great stake

on a single strategy with an uncertain method of solution; there was not enough money in the treasury; negotiations with other Italian states were uncertain; the Swiss might

ally themselves with France; and the area would soon be fraught with

danger from the impending winter. However, Gattinara argued that the

war was justified by Charles V’s bond to honor the Pope, whom he needed as an ally. Clearly, God was on Charles’s side, and to let France escape a fight would be to tempt fate — he

would not have the chance, as resources would not be mobilized so

easily next time. Additionally, with the army mobilized, it would not

look good to call it off at the eleventh hour. Gattinara saw to it that

his ten commandments won out over the seven deadly sins. Gattinara was not an idealist when it came to policy. The Treaty of Madrid was forced upon Francis I of France by Charles after Francis was captured. The treaty spoke in romantic hyperbole and ended with an oath for both rulers to undertake a crusade together. While François signed the treaty under duress, Gattinara refused

to affix the imperial seal to the document, because of his sense of realpolitik.

François would subsequently break the terms of the treaty, which

had been to renounce claims in Italy, surrender Burgundy, and abandon suzerainty over Flanders and Artois.“ Sire,

God has been very merciful to you: he has raised you above all the

Kings and princes of Christendom to a power such as no sovereign has

enjoyed since your ancestor Charles the Great. He has set you on the way towards a world monarchy, towards the uniting of all Christendom under a single shepherd. ” “ At this moment one may say that Your Majesty holds world - monarchy in your hands, provided this victory over France is turned to good advantage. If the English were

to set foot in France, it would be a great advantage for Your Majesty,

for it would weaken the enemy and prevent him from doing any further

damage, and thus the surest means to a lasting peace. The whole of Languedoc, Burgundy, and the land about the River Somme should be regained. God made Emperor the arbitrator between peace and war. Such favorable opportunity should not be lost. ” “ It

appears God has bestowed this victory on the Emperor in a wonderful

manner, so that he might defend Christendom and fight the Turks and

Moors on their own ground, so that the whole world receive our Holy Faith under this Christian Prince and the words of Our Savior be fulfilled: Fiet unum ovile et unus pastor. ”