<Back to Index>

- Physician Karl Landsteiner, 1868

- Photographer John Thomson, 1837

- Geologist and Experimental Farmer James Hutton, 1726

PAGE SPONSOR

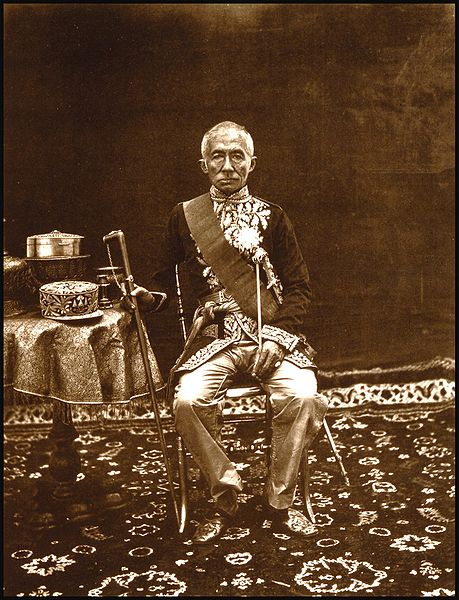

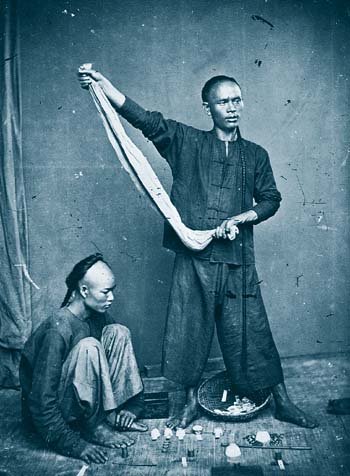

John Thomson (14 June 1837 – 29 September 1921) was a pioneering Scottish photographer, geographer and traveller. He was one of the first photographers to travel to the Far East, documenting the people, landscapes and artifacts of eastern cultures. Upon returning home, his work among the street people of London cemented his reputation, and is regarded as a classic instance of social documentary which laid the foundations for photojournalism. He went on to become a portrait photographer of High Society in Mayfair, gaining the Royal Warrant in 1881.

The son of William Thomson, a tobacco spinner and retail trader, and his wife Isabella, Thomson was born the eighth of nine children in Edinburgh in the year of Queen Victoria's accession. After his schooling in the early 1850s, he was apprenticed to a local optical and scientific instrument manufacturer, thought to be James Mackay Bryson. During this time, Thomson learned the principles of photography and completed his apprenticeship around 1858.

During

this time he also undertook two years of evening classes at the Watt

Institution and School of Arts (formerly the Edinburgh School of Arts,

later to become Heriot - Watt University). He received the "Attestation of Proficiency" in Natural Philosophy in 1857 and in Junior Mathematics and Chemistry in 1858. In 1861 he became a member of the Royal Scottish Society of Arts, but by 1862 he had decided to travel to Singapore to join his older brother William, a watchmaker and photographer. In

April 1862, Thomson left Edinburgh for Singapore, beginning a ten year

period spent travelling around the Far East. Initially, he established

a joint business with William to manufacture marine chronometers and optical and nautical instruments. He also established a photographic studio in Singapore, taking portraits of European merchants,

and he developed an interest in local peoples and places. He travelled

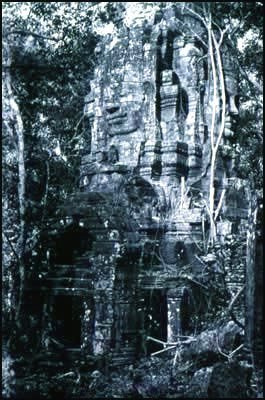

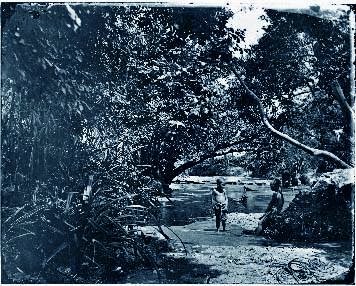

extensively throughout the mainland territories of Malaya and the island of Sumatra, exploring the villages and photographing the native peoples and their activities. After visiting Ceylon and India from October to November 1864 to document the destruction caused by a recent cyclone, Thomson sold his Singapore studio and moved to Siam. After arrival in Bangkok in September 1865, Thomson undertook a series of photographs of the King of Siam and other senior members of the royal court and government. Inspired by Henri Mouhot’s account of the rediscovery of the ancient cities of Angkor in the Cambodian jungle,

Thomson embarked on what would become the first of his major

photographic expeditions. He set off in January 1866 with his translator H.G. Kennedy, a British Consular official in Bangkok, who saved Thomson's life when he contracted jungle fever en route. The pair spent two weeks at Angkor, where Thomson extensively

documented the vast site, producing some of the earliest photographs of

what is today a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Thomson then moved on to Phnom Penh and took photographs of the King of Cambodia and other members of the Cambodian Royal Family, before travelling on to Saigon. From there he stayed in Bangkok briefly, before returning to Britain in May or June in 1866. While back home, Thomson lectured extensively to the British Association and published his photographs of Siam and Cambodia. He became a member of the Royal Ethnological Society of London and was elected a Fellow of the Royal Geographic Society in 1866, and published his first book, The Antiquities of Cambodia, in early 1867. After

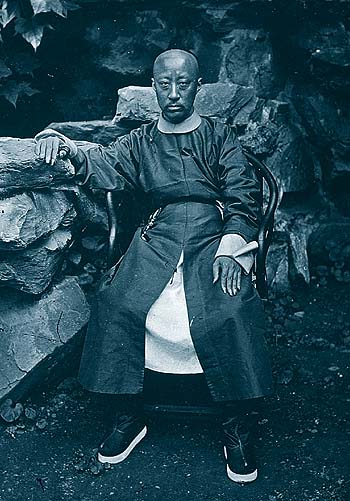

a year in Britain, Thomson again felt the desire to return to the Far

East. He returned to Singapore in July 1867, before moving to Saigon

for three months and finally settling in Hong Kong in 1868. He established a studio in the Commercial Bank building, and spent the next four years photographing the people of China and recording the diversity of Chinese culture. Thomson travelled extensively throughout China, from the southern trading ports of Hong Kong and Canton to the cities of Peking and Shanghai, to the Great Wall in the north, and deep into central China. From 1870 to 1871 he visited the Fukien region, travelling up the Min River by boat with the American Protestant missionary Reverend Justus Doolittle, and then visited Amoy and Swatow. He went on to visit the island of Formosa with the missionary Dr. James Laidlaw Maxwell, landing first in Takao in early April 1871. The pair visited the capital, Taiwanfu, before travelling on to the aboriginal villages

on the west plains of the island. After leaving Formosa, Thomson spent

the next three months travelling 3,000 miles up the Yangtze River, reaching Hupeh and Szechuan. Thomson's

travels in China were often perilous, as he visited remote, almost

unpopulated regions far inland. Most of the people he encountered had

never seen a Westerner or camera before. His expeditions were also

especially challenging because he had to transport his bulky wooden

camera, many large, fragile glass plates, and potentially explosive

chemicals. He photographed in a wide variety of conditions and often

had to improvise because chemicals were difficult to acquire. His

subject matter varied enormously: from humble beggars and street people

to Mandarins, Princes and

senior government officials; from remote monasteries to Imperial

Palaces; from simple rural villages to magnificent landscapes. Thomson returned to England in 1872, settling in Brixton, London, and, apart from a final photographic journey to Cyprus in

1878, Thomson never left again. Over the coming years he proceeded to

lecture and publish, presenting the results of his travels in the Far

East. His publications started initially in monthly magazines and were

followed by a series of large, lavishly illustrated photographic books.

He wrote extensively on photography, contributing many articles to

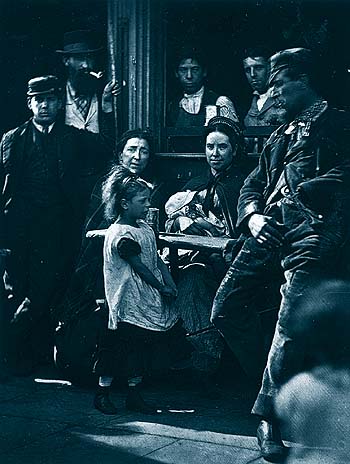

photographic journals such as the British Journal of Photography. He also translated and edited Gaston Tissandier’s 1876 History and Handbook of Photography, which became a standard reference work. In London, Thomson renewed his acquaintance with Adolphe Smith,

a radical journalist whom he had met at the Royal Geographic Society in

1866. Together they collaborated in producing the monthly magazine, Street Life in London,

from 1876 to 1877. The project documented in photographs and text the

lives of the street people of London, establishing social documentary

photography as an early type of photojournalism. The series of

photographs was later published in book form in 1878. With

his reputation as an important photographer well established, Thomson

opened a portrait studio in Buckingham Palace Road in 1879, later

moving it to Mayfair. In 1881 he was appointed photographer to the

British Royal Family by Queen Victoria, and his later work concentrated

on studio portraiture of the rich and famous of High Society, giving

him a comfortable living. From January 1886 he began instructing

explorers at the Royal Geographical Society in the use of photography to document their travels. After

retiring from his commercial studio in 1910, Thomson spent most of his

time back in Edinburgh, although he continued to write papers for the

Royal Geographical Society on the uses of photography. He died of a

heart attack in 1921 at the age of 84. Thomson

was an accomplished photographer in many areas: landscapes,

portraiture, street photography, architectural photography, and his

legacy is one of outstanding quality and breadth of coverage. His

photography from the Far East enlightened the Victorian audience of

Britain about the land, people and cultures of China and South - East

Asia. His pioneering work documenting the social conditions of the

street people of London established him as one of the pioneers of

photojournalism, and his publishing activities mark him out as an

innovator in combining photography with the printed word. In recognition of his work, one of the peaks of Mount Kilimanjaro was

named "Point Thomson" on his death in 1921. Some of Thomson's work may

be seen at the Royal Geographical Society's headquarters in London.