<Back to Index>

- Statistician John Wilder Tukey, 1915

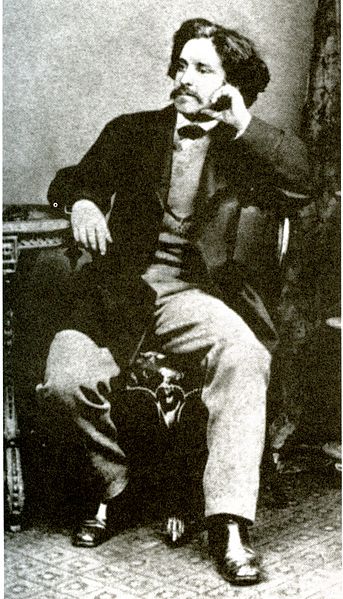

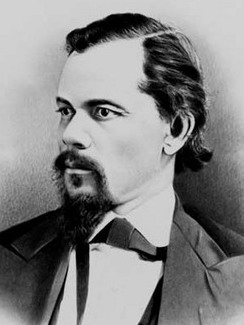

- Writer and Marxist Socialist Journalist Paul Lafargue, 1842

- Cossack Revolutionary Stepan Timofeyevich (Stenka) Razin, 1630

PAGE SPONSOR

Paul Lafargue (June 16, 1842 – November 26, 1911) was a French revolutionary Marxist socialist journalist, literary critic, political writer and activist; he was Karl Marx's son - in - law, having married his second daughter Laura. His best known work is The Right to Be Lazy. Born in Cuba to French and Creole parents, Lafargue spent most of his life in France, with periods in England and Spain. At the age of 69, he and Laura died together in a suicide pact.

Lafargue was the subject of a famous quotation by Karl Marx. Shortly before Marx died in 1883, he wrote a letter to Lafargue and the French Workers' Party leader Jules Guesde,

both of whom already claimed to represent "Marxist" principles. Marx

accused them of "revolutionary phrase - mongering" and of denying the

value of reformist struggles. This exchange is the source of Marx's remark, reported by Friedrich Engels: "ce qu'il y a de certain c'est que moi, je ne suis pas Marxiste" ("what is certain is that [if they are Marxists, then] I myself am not a Marxist"). Lafargue was born in Santiago de Cuba. His father was the owner of coffee plantations in Cuba, and the family's wealth allowed Lafargue to study in Santiago and then in France. In 1851, the Lafargue family moved to Bordeaux — Lafargue finished lycée in Toulouse, and studied medicine in Paris. It was there that Lafargue started his intellectual and political career, adhering to the Positivist philosophy, and contacting the Republican groups that opposed Napoleon III. The work of Pierre - Joseph Proudhon seem to have particularly influenced him in this phase. As a Proudhonian anarchist, Lafargue joined the French section of the International Workingmen's Association (the First International). Nevertheless, he soon contacted two of the most prominent figures of revolutionary thought and action: Marx and Auguste Blanqui, whose influence largely eclipsed the first anarchist tendencies of the young Lafargue. In 1865, after participating in the International Students' Congress in Liege, Lafargue was banned from all French universities, and had to leave for London in

order to start a career. It was there that he became a frequent visitor

to Marx's house, meeting his second daughter Laura, whom he married in

1868. His political activity took a new course, and he was chosen as a

member of the General Council of the First International, then

appointed corresponding secretary for Spain. However, he does not seem

to have succeeded in establishing any serious contact with workers'

groups in that country - Spain joined the international movement only

after the Cantonalist Revolution of 1868, while events such as the arrival of the Italian anarchist Giuseppe Fanelli made it a strong bastion of Anarchism (and not of the Marxist current that Lafargue chose to represent). Lafargue's

opposition to Anarchism became notorious when, after his return to

France, he wrote several articles attacking the Bakuninist tendencies

that were very influential in some French workers' groups; this series

of articles marked the start of a long career as a political journalist. After the revolutionary episode of the Paris Commune in 1871, political repression forced him to flee to Spain. He finally settled in Madrid, where he contacted those local members of the International over whom his influence was going to be very important. Unlike in other parts of Europe where Marxism came to play a dominant part, Spain's revolutionaries were mostly followers of the International's anarchist faction (they were to remain very strong up until the Spanish Civil War of the 1930s, and the subsequent dictatorship).

Lafargue became involved in redirecting the trend toward Marxism, an

activity that was largely developed under directions from Friedrich Engels,

and one that became intertwined with the struggles that both tendencies

had at the international level - as the Spanish federation of the

International was one of the main pillars of the Anarchist group. The task given to Lafargue consisted mainly of gathering a Marxist leadership in Madrid, while exercising an ideological influence through unsigned articles in the newspaper La Emancipación (where he defended the need to create a political party of the working class,

one of the main topics opposed by the anarchists). At the same time,

Lafargue took initiative through some of his articles, expressing his

own ideas about a radical reduction of the working day (a concept which was not entirely alien to the original thought of Marx). In 1872, after a public attack of La Emancipación against

the new, anarchist, Federal Council, the Federation of Madrid expelled

the signatories of that article, who soon went on to found the New Federation of Madrid,

a group of limited influence. The last activity of Lafargue as a

Spanish activist was to represent this Marxist minority group in the

1872 Hague Congress which marked the end of First International as a united group of all communists. Between

1873 and 1882, Paul Lafargue lived in London, and avoided practising

medicine as he had come to lose faith in it. He opened a photolithography workshop,

but its limited income forced him to request money from Engels (who was

an owner of industries) on several occasions. Thanks to Engels'

assistance, he again contacted the French workers' movement from London, after it had started to regain ground lost with the reactionary repression under Adolphe Thiers during the first years of the Third Republic. From 1880, he again worked as editor of the newspaper L'Egalité. In that same year, and in the pages of that publication, Lafargue began publishing the first draft of The Right to Be Lazy. In 1882, he started working in an insurance company, which allowed him to move back to Paris and re-enter the core of French socialist politics. Together with Jules Guesde and Gabriel Deville, he began directing the activities of the newly founded French Workers' Party (Parti Ouvrier Français; POF), which he led into conflict with the other major left wing options: Anarchism, as well as the "Jacobin" Radicals and Blanquists. From

then until his death, Lafargue remained the most respected theorist of

the POF, not just extending the original Marxist doctrines, but also

adding original ideas of his own. He also took active part in public

activities such as strikes and elections, and was imprisoned several times. In 1891, despite being in police custody, he was elected to the French Parliament for Lille,

being the first ever French Socialist to occupy such an office. His

success would encourage the POF to remain engaged in electoral

activities, and largely abandon the insurrectional policies of its previous period. Nevertheless, Lafargue continued his defense of Marxist orthodoxy against any reformist tendency, as shown by his conflict with Jean Jaurès, as well as his refusal to take part in any "bourgeois" government. In 1908, the different socialist tendencies were unified in the form of a single party after a Congress in Toulouse. Lafargue made his last stand in the gathering, fighting fiercely against the social democrat reformism defended by Jaurès. In

these late years, Lafargue had already distanced himself from any form

of political activity, living on the outskirts of Paris in the village

of Draveil,

limiting his contributions to a number of articles and essays, as well

as occasional contacts with some of the most outstanding socialist

activists of the time, such as Karl Kautsky and Hjalmar Branting of the older generation, and Karl Liebknecht or Vladimir Lenin of the younger generation. It was in Draveil that Paul and Laura Lafargue put an end to their lives, to the surprise and even outrage of French and European socialists. He wrote on that occasion: Most socialist leaders publicly or privately deplored his decision; a few, notably the Spanish Anarchist leader Anselmo Lorenzo, who had been a major political rival of Lafargue in his Spanish period,

accepted his decision with understanding. Lorenzo wrote after

Lafargue's death: Adolf Abramovich Joffe who later himself committed suicide to protest against the expulsion of Leon Trotsky from the Central Committee of

the Soviet Communist Party noted in his final letter to Trotsky on the

verge of committing suicide that he supported the suicide pact of

Lafargue and Marx in his youth: