<Back to Index>

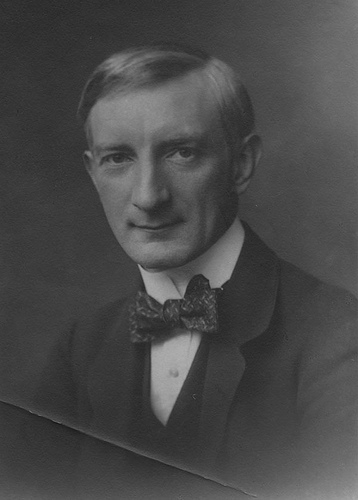

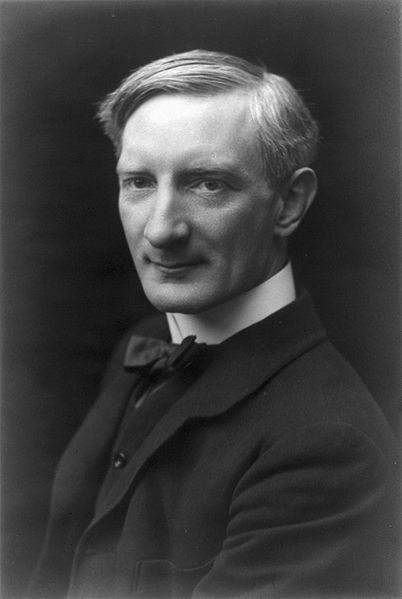

- Economist William Henry Beveridge, 1879

- Writer Vasily Kirillovich Trediakovsky, 1703

- King of Hungary and Croatia Louis I the Great, 1326

PAGE SPONSOR

William Henry Beveridge, 1st Baron Beveridge KCB (5 March 1879 – 16 March 1963) was a British economist and social reformer. He is best known for his 1942 report Social Insurance and Allied Services (known as the Beveridge Report) which served as the basis for the post World War II welfare state put in place by the Labour government elected in 1945.

Considered an authority on unemployment insurance from early in his career, he served under Winston Churchill on the Board of Trade as director of the newly created labour exchanges and later as permanent secretary of the Ministry of Food. He was Director of the London School of Economics and Political Science from 1919 until 1937, when he was elected master of University College, Oxford.

He published widely on unemployment and social security, his most notable works being: Unemployment: A Problem of Industry (1909), Planning Under Socialism (1936), Full Employment in a Free Society (1944), Pillars of Security (1948), Power and Influence (1953), and A Defence of Free Learning (1959).

Beveridge, the eldest son of Henry Beveridge, an Indian Civil Service officer and scholar Annette Akroyd, was born in Rangpur, India (now Rangpur, Bangladesh), on 5 March 1879. After studying at Charterhouse School and Balliol College, Oxford, he became a lawyer. Beveridge became interested in the social services and wrote about the subject for the Morning Post newspaper. His interest in the causes of unemployment began in 1903 when he worked at Toynbee Hall, a settlement house in London. There he worked closely with Sidney Webb and Beatrice Webb and was influenced by their theories of social reform, becoming active in promoting old age pensions, free school meals, and campaigning for a national system of labour exchanges. In 1908, now considered to be the United Kingdom's leading authority on unemployment insurance, he was introduced by Beatrice Webb to Winston Churchill, who had recently promoted to the Cabinet as President of the Board of Trade.

Churchill invited Beveridge to join the Board of Trade, and he

organised the implementation of the national system of labour exchanges

and National Insurance to combat unemployment and poverty. During the First World War he was involved in mobilising and controlling manpower. After the war, he was knighted and made permanent secretary to the Ministry of Food. In 1919 he left the civil service to become director of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Over the next few years he served on several commissions and committees on social policy. He was so highly influenced by the Fabian Society socialists — in particular by Beatrice Webb, with whom he worked on the 1909 Poor Laws report

— that he could readily be considered one of their number. He published

academic economic works including his early work on unemployment (1909)

and a large historical study of prices and wages (1939). The Fabians

made him a director of the LSE in 1919, a post he retained until 1937.

During his time as Director, he jousted with Cannan and Robbins, who were trying to steer the LSE away from its Fabian roots. In 1933 he helped set up the Academic Assistance Council. This helped prominent German Jewish academics escape Nazi persecution. In 1937, Beveridge was appointed Master of University College, Oxford.

Three years later, Ernest Bevin,

Minister of Labour in the wartime National government, invited

Beveridge to take charge of the Welfare department of his Ministry.

Beveridge refused, but declared an interest in organising British

manpower in wartime (Beveridge had come to favour a strong system of

centralised planning). Bevin was reluctant to let Beveridge have his

way but did commission him to work on a relatively unimportant manpower

survey from June 1940 and so Beveridge became a temporary civil

servant. Neither Bevin nor the Permanent Secretary of the Ministry Sir

Thomas Phillips liked working with Beveridge as both found him

conceited.

An opportunity for Bevin to ease Beveridge out presented itself in May 1941 when Minister of Health

Ernest Brown announced

the formation of a committee of officials to survey existing social

insurance and allied services, and to make recommendations. Although

Brown had made the announcement, the inquiry had largely been urged by

Minister without Portfolio Arthur Greenwood,

and Bevin suggested to Greenwood making Beveridge chairman of the

committee. Beveridge, at first uninterested and seeing the committee as

a distraction from his work on manpower, accepted only reluctantly. The Report to the Parliament on Social Insurance and Allied Services was published in 1942. It proposed that all people of working age should pay a weekly national insurance contribution.

In return, benefits would be paid to people who were sick, unemployed,

retired or widowed. Beveridge argued that this system would provide a

minimum standard of living "below which no one should be allowed to

fall". It recommended that the government should find ways of fighting

the five 'Giant Evils' of Want, Disease, Ignorance, Squalor and

Idleness. Beveridge included as one of three fundamental assumptions

the fact that there would be a National Health Service of some sort, a

policy already being worked on in the Ministry of Health. Beveridge's

arguments were widely accepted. He appealed to conservatives and other

doubters by arguing that welfare institutions would increase the

competitiveness of British industry in the post war period, not only by

shifting labour costs like healthcare and pensions out of corporate ledgers

and onto the public account, but also by producing healthier, wealthier

and thus more motivated and productive workers who would also serve as

a great source of demand for British goods. Beveridge saw full employment (defined as unemployment of no more than 3%) as the pivot of the social welfare programme he expressed in the 1942 report. Full Employment in a Free Society, written in 1944 expressed how this goal might be gained. Alternative measures for achieving it included Keynesian style

fiscal regulation, direct control of manpower, and state control of the

means of production. The impetus behind Beveridge's thinking was social justice,

and the creation of an ideal new society after the war. He believed

that the discovery of objective socio - economic laws could solve the

problems of society. Later in 1944, Beveridge, who had recently joined the Liberal Party, was elected to the House of Commons in a by-election to succeed George Charles Grey, who had died on the battlefield in Normandy, France, on the first day of Operation Bluecoat on 30 July 1944. Beveridge briefly served as Member of Parliament (MP) for the constituency of Berwick - upon - Tweed until the 1945 general election. The

following year the new Labour Government began the process of

implementing Beveridge's proposals that provided the basis of the

modern Welfare State. Clement Attlee and the Labour Party defeated Winston Churchill's Conservative Party in the 1945 general election.

Attlee announced he would introduce the Welfare State outlined in the

1942 Beveridge Report. This included the establishment of a National Health Service in 1948 with

taxpayer funded medical treatment for all. A national system of

benefits was also introduced to provide 'social security' so that the

population would be protected from the 'cradle to the grave'. The new

system was partly built on the National Insurance scheme set up by Lloyd George in 1911. In 1946 Beveridge was raised to the peerage as Baron Beveridge, of Tuggal in the County of Northumberland, and eventually became leader of the Liberals in the House of Lords. He was the author of Power and Influence (1953). Beveridge was a member of the Eugenics Society, which promoted the study of methods to 'improve' the human race by controlling reproduction.

In 1909, he proposed that men who could not work should be supported by

the state "but with complete and permanent loss of all citizen rights —

including not only the franchise but civil freedom and fatherhood." Whilst

director of the London School of Economics, Beveridge attempted to

create a Department of Social Biology. Though never fully established, Lancelot Hogben, a fierce anti - eugenicist, was named its Chair. Former LSE Director John Ashworth speculated that discord between those in favour and those against the serious

study of eugenics led to Beveridge's departure from the school in 1937. In the 1940s, Beveridge credited the Eugenics Society with promoting the children's allowance,

which was incorporated into his 1942 report. However, whilst he held

views in support of eugenics, he did not believe the report had any

overall "eugenic value". Professor Danny Dorlingof the University of Sheffield says "there is not even the faintest hint" of eugenic thought in the report.

Lord

Beveridge married Jessy Janet, daughter of William Philip and widow of

David Mair, in 1942. He died at his home on 16 March 1963, aged 84, and

was buried in Thockrington churchyard, on the Northumbrian moors. His

barony became extinct upon his death. His last words, as he sat up in

bed whilst still working on his 'History of Prices', were "I have a

thousand things to do".