<Back to Index>

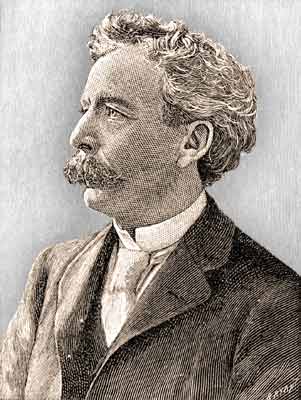

- Botanist Luther Burbank, 1849

- Painter Boris Mikhaylovich Kustodiev, 1878

- Prime Minister of France Jacques Chaban - Delmas, 1915

PAGE SPONSOR

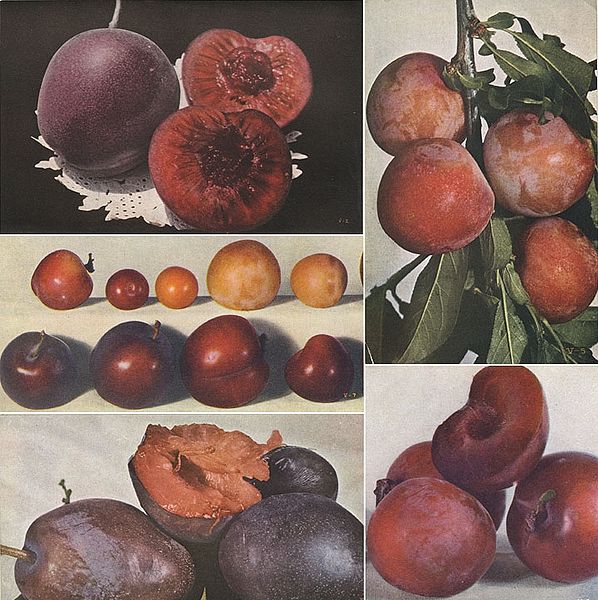

Luther Burbank (7 March 1849 – 11 April 1926) was an American botanist, horticulturist and a pioneer in agricultural science.

He

developed more than 800 strains and varieties of plants over his

55 year career. Burbank's varied creations included fruits, flowers, grains, grasses, and vegetables. He

developed a spineless cactus (useful

for cattle feed) and the plumcot. Burbank's most

successful strains and varieties include the Shasta daisy, the Fire poppy, the July Elberta peach, the Santa Rosa plum, the Flaming Gold nectarine, the Wickson plum, the Freestone peach, and the white

blackberry. A

natural genetic

variant of

the Burbank potato with russet

- colored skin

later became known as the Russet Burbank potato. This large, brown

skinned, white fleshed potato has become the world's

predominant potato in food

processing.

Born in Lancaster, Massachusetts, Burbank grew up on a farm and received only an elementary school education. The thirteenth of fifteen children, he enjoyed the plants in his mother's large garden. His father died when he was 21 years old, and Burbank used his inheritance to buy a 17 acre (69,000 m²) plot of land near Lunenburg center. There, he developed the Burbank potato. Burbank sold the rights to the Burbank potato for $150 and used the money to travel to Santa Rosa, California, in 1875. Later, a natural sport of Burbank potato with russetted skin was selected and named Russet Burbank potato. Today, the Russet Burbank potato is the most widely cultivated potato in the United States. A large percentage of McDonald's french fries are made from this cultivar.

In Santa Rosa, Burbank purchased a 4 acre (16,000 m2) plot of land, and established a greenhouse, nursery, and experimental fields that he used to conduct crossbreeding experiments on plants, inspired by Charles Darwin's The Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication. (This site is now open to the public as a city park, Luther Burbank Home and Gardens.) Later he purchased an 18 acre (7.3 ha) plot of land in the nearby town of Sebastopol called Gold Ridge Farm.

From 1904 through 1909 Burbank received several grants from the Carnegie Institution to support his ongoing research on hybridization. He was supported by the practical minded Andrew Carnegie himself, over those of his advisers who objected that Burbank was not "scientific" in his methods.

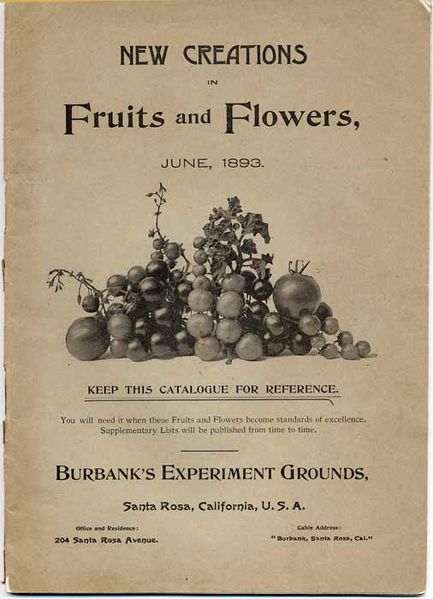

Burbank became known

through his plant catalogs, the most famous being

1893's "New Creations in Fruits and Flowers," and

through the word of mouth of satisfied customers, as

well as press reports that kept him in the news

throughout the first decade of the century.

Burbank created hundreds of new varieties of fruits (plum, pear, prune, peach, blackberry, raspberry); potato, tomato; ornamental flowers and other plants.

Burbank was criticized by scientists of his day because he did not keep the kind of careful records that are the norm in scientific research and because he was mainly interested in getting results rather than in basic research. Jules Janick, Ph.D., Professor of Horticulture and Landscape Architecture, Purdue University, writing in the World Book Encyclopedia, 2004 edition, says: "Burbank cannot be considered a scientist in the academic sense."

In 1893, Burbank published a descriptive catalog of some of his best varieties, entitled New Creations in Fruits and Flowers.

In 1907, Burbank published an “essay on childrearing,” called The Training of the Human Plant. In it, he advocated improved treatment of children and eugenic practices such as keeping the unfit and first cousins from marrying.

During his career, Burbank wrote, or co-wrote, several books on his methods and results, including his eight volume How Plants Are Trained to Work for Man (1921), Harvest of the Years (with Wilbur Hall, 1927), Partner of Nature (1939), and the 12 volume Luther Burbank: His Methods and Discoveries and Their Practical Application.

Burbank experimented with a

variety of techniques such as grafting,

hybridization, and cross breeding.

Intraspecific hybridization within a plant species was demonstrated by Charles Darwin and Gregor Mendel, and was further developed by geneticists and plant breeders.

In 1908, George Harrison Shull described heterosis, also known as hybrid vigor. Heterosis describes the tendency of the progeny of a specific cross to outperform both parents. The detection of the usefulness of heterosis for plant breeding has led to the development of inbred lines that reveal a heterotic yield advantage when they are crossed. Maize was the first species where heterosis was widely used to produce hybrids.

By the 1920s, statistical methods were developed to analyze gene action and distinguish heritable variation from variation caused by environment. In 1933, another important breeding technique, cytoplasmic male sterility (CMS), developed in maize, was described by Marcus Morton Rhoades. CMS is a maternally inherited trait that makes the plant produce sterile pollen. This enables the production of hybrids without the need for labour intensive detasseling.

These early breeding techniques

resulted in large yield increase in the United States in the

early 20th century. Similar yield increases were not

produced elsewhere until after World War II, the Green Revolution increased

crop production in the developing world in the 1960s.

Classical plant breeding uses deliberate interbreeding (crossing) of closely or distantly related individuals to produce new crop varieties or lines with desirable properties. Plants are crossbred to introduce traits / genes from one variety or line into a new genetic background. For example, a mildew resistant pea may be crossed with a high yielding but susceptible pea, the goal of the cross being to introduce mildew resistance without losing the high yield characteristics. Progeny from the cross would then be crossed with the high yielding parent to ensure that the progeny were most like the high yielding parent, (backcrossing). The progeny from that cross would then be tested for yield and mildew resistance and high yielding resistant plants would be further developed. Plants may also be crossed with themselves to produce inbred varieties for breeding.

Classical breeding relies largely on homologous recombination between chromosomes to generate genetic diversity. The classical plant breeder may also makes use of a number of in vitro techniques such as protoplast fusion, embryo rescue or mutagenesis to generate diversity and produce hybrid plants that would not exist in nature.

Traits that breeders have tried to incorporate into crop plants in the last 100 years include:

Burbank cross pollinated the flowers of plants by hand and planted all the resulting seeds. He then selected the most promising plants to cross with other ones.By all accounts, Burbank was a kindly man who wanted to help other people. He was very interested in education and gave money to the local schools. He married twice: to Helen Coleman in 1890, which ended in divorce in 1896; and to Elizabeth Waters in 1916. He had no children.

His friend and admirer Paramahansa Yogananda wrote in his Autobiography of a Yogi:

- "His heart was fathomlessly deep, long acquainted with humility, patience, sacrifice. His little home amid the roses was austerely simple; he knew the worthlessness of luxury, the joy of few possessions. The modesty with which he wore his scientific fame repeatedly reminded me of the trees that bend low with the burden of ripening fruits; it is the barren tree that lifts its head high in an empty boast."

In a speech given to the First Congregational Church of San Francisco in 1926, Burbank said:

- "I love humanity, which has been a constant delight to me during all my seventy - seven years of life; and I love flowers, trees, animals, and all the works of Nature as they pass before us in time and space. What a joy life is when you have made a close working partnership with Nature, helping her to produce for the benefit of mankind new forms, colors, and perfumes in flowers which were never known before; fruits in form, size, and flavor never before seen on this globe; and grains of enormously increased productiveness, whose fat kernels are filled with more and better nourishment, a veritable storehouse of perfect food — new food for all the world's untold millions for all time to come."

In mid March 1926, Burbank suffered a heart attack and became ill with gastrointestinal complications. He died on April 11, 1926, aged 77, and is buried near the greenhouse at the Luther Burbank Home and Gardens.

His last

words were: "I don't feel good."

Burbank's work spurred the passing of the 1930 Plant Patent Act four years after his death. The legislation made it possible to patent new varieties of plants (excluding tuber - propagated plants). In supporting the legislation, Thomas Edison testified before Congress in support of the legislation and said that "This [bill] will, I feel sure, give us many Burbanks." The authorities issued Plant Patents #12, #13, #14, #15, #16, #18, #41, #65, #66, #235, #266, #267, #269, #290, #291, and #1041 to Burbank posthumously.

In 1986, Burbank was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame. The Luther Burbank Home and Gardens, in downtown Santa Rosa, are now designated as a National Historic Landmark. Luther Burbank's Gold Ridge Experiment Farm is listed in the National Register of Historic Places a few miles west of Santa Rosa in the town of Sebastopol, California.

The home that Luther Burbank was born in, as well as his California garden office, were moved by Henry Ford to Dearborn, Michigan, and are part of Greenfield Village.