<Back to Index>

- Navigator and Cartographer Captain Matthew Flinders, 1774

- Poet Bengt Lidner, 1757

- Father of Japanese Capitalism Shibusawa Eiichi, 1840

PAGE SPONSOR

Captain Matthew Flinders RN (16 March 1774 – 19 July 1814) was one of the most successful navigators and cartographers of his age. In a career that spanned just over twenty years, he sailed with Captain William Bligh, circumnavigated Australia and encouraged the use of that name for the continent, which had previously been known as New Holland. He survived shipwreck and disaster only to be imprisoned for violating the terms of his scientific passport by changing ships and carrying prohibited papers. He identified and corrected the effect upon compass readings of iron components and equipment on board wooden ships and he wrote a work on early Australian exploration A Voyage to Terra Australis.

Born in Donington, Lincolnshire, England, the son of Matthew Flinders, a surgeon, and his wife Susannah, née Ward. In his own words, he was "induced to go to sea against the wishes of my friends from reading Robinson Crusoe", and at the age of fifteen he joined the Royal Navy in 1789.

Initially serving on HMS Alert, he transferred to HMS Scipio, and in July 1790 was made midshipman on HMS Bellerophon under Captain Pasley. By Pasley's recommendation, he joined Captain Bligh's expedition on HMS Providence, transporting breadfruit from Tahiti to Jamaica. This was also young Flinders' first look at Australian waters landing at Adventure Bay, Tasmania, in 1792. Upon his return to England, he rejoined the Bellerophon, in which he saw action at the Glorious First of June. Flinders first trip to Port Jackson was in 1795 as a midshipman aboard HMS Reliance, carrying the newly appointed Governor of New South Wales Captain John Hunter. On this voyage he quickly established himself as a fine navigator and cartographer, and became friends with the ship's surgeon George Bass. Not long after their arrival in Port Jackson, Bass and Flinders made two expeditions in small open boats, both boats were called Tom Thumb: the first to Botany Bay and Georges River, the second in a larger boat south from Port Jackson to Lake Illawarra. In 1798, Flinders, who was now a Lieutenant, was given command of the Norfolk and orders "to sail beyond Furneaux's Islands, and, should a strait be found, pass through it, and return by the south end of Van Diemen's Land".

The passage between the Australian mainland and Tasmania enabled

savings of several days on the journey from England, and was named Bass Strait, after his close friend. In honour of this discovery, the largest island in Bass Strait would later be named Flinders Island. The town of Flinders near the mouth of Western Port also

commemorates Bass' discovery of that bay and port on 4 January

1798. Flinders never entered Western Port, and only pass Cape Schanck on

the 3rd. May 1802. Flinders once more sailed the Norfolk, this time North on 17 July 1799, he arrived in Moreton Bay between Redcliffe and Brighton. He touched down at Pumicestone Passage, Redcliffe and Coochiemudlo Island and also rowed ashore at Clontarf. During this visit he named Redcliffe after the Red Cliffs. In March 1800, Flinders rejoined the Reliance which set sail for England. Flinders' work had come to the attention of many of the scientists of the day, in particular the influential Sir Joseph Banks, to whom Flinders dedicated his Observations on the Coasts of Van Diemen's Land, on Bass's Strait, etc.. Banks used his influence with Earl Spencer to convince the Admiralty of

the importance of an expedition to chart the coastline of New Holland.

As a result, in January 1801, Flinders was given command of the Investigator, a 334 ton sloop, and promoted to Commander the following month. The Investigator set sail for New Holland on 18 July 1801. Attached to the expedition was the botanist Robert Brown, botanical artist Ferdinand Bauer and landscape artist William Westall. Due to the scientific nature of the expedition, Flinders was issued with a French passport, despite England and France then being at war.

On 17 April 1801, Flinders had married longtime friend Ann Chappelle (1772 – 1852).

Flinders hoped to bring her with him to Port Jackson contrary to the

Admiralty's rules against wives accompanying captains. Despite these

rules, Flinders brought her on board and meant to take her to

Australia, though his attempt was discovered when his ship ran aground

while they were below deck, subsequently he was chastised by the

Admiralty. As a result, she was obliged to stay in England, and they

would not see each other for nine years. Matthew and Ann had one

daughter, Anne, born 1 April 1812, who later married William Petrie

(1821 - 1908) and was the mother of the eminent archaeologist and

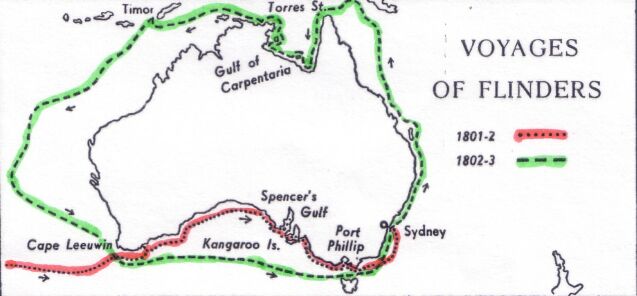

Egyptologist, William Matthew Flinders Petrie. Flinders reached and named Cape Leeuwin on 6 December 1801, and proceeded to make a survey along the southern coast of the Australian mainland. On 8 April 1802 while sailing east Flinders sighted the Géographe, a French corvette commanded by the explorer Nicolas Baudin, who was on a similar expedition for his government. Both men of science, Flinders and Baudin met and exchanged details of their discoveries, Flinders named the bay Encounter Bay. Proceeding along the coast, Flinders explored Port Phillip, which unbeknownst to him had been discovered only 10 weeks earlier by John Murray aboard the Lady Nelson. Flinders scaled Arthur's Seat, the highest point near the shores of the southernmost parts of the bay, where the ship had entered through The He ads.

From there he saw a vast view of the surrounding land and bays.

Flinders reported back to Governor King that the land had 'a pleasing

and, in many parts, a fertile appearance'. He

stated on 1 May, "I left the ship's name on a scroll of paper,

deposited in a small pile of stones upon the top of the peak". Here,

Flinders was drawing upon a British tradition of constructing a stone cairn to

mark a historical location. The Matthew Flinders Cairn, which was later

enlarged, is located on the upper slopes of Arthurs Seat a short

distance below Chapman's Point. With stores running low, Flinders proceeded to Sydney, arriving 9 May 1802. Having

hastily prepared the ship, Flinders set sail again on 22 July, heading

north and surveying the coast of Queensland. From there he passed

through the Torres Strait, and explored the Gulf of Carpentaria. During this time, the ship was discovered to be badly leaking, and despite careening,

they were unable to effect the necessary repairs. Reluctantly, Flinders

returned to Sydney, though via the western coast, completing the

circumnavigation of the continent. On the way, Flinders jettisoned two

wrought iron anchors, one of which was found by divers in 1973 at

Middle Island, Recherche Archipelago, Western Australia. This anchor may be seen at the National Museum of Australia. Arriving in Sydney 9 June 1803, the Investigator was subsequently judged to be unseaworthy and condemned. Unable to find another vessel suitable to continue his exploration, Flinders set sail for England as a passenger aboard HMS Porpoise. However the ship was wrecked on the Great Barrier Reef, approximately 700 miles (1127 km) north of Sydney. Flinders navigated the ship's cutter across open sea back to Sydney, and arranged for the rescue of the remaining marooned crew. Flinders then took command of the 29 ton schooner Cumberland in order to return to England, but the poor condition of the vessel forced him to put in at French controlled Mauritius for repairs on 17 December 1803. War with France had

broken out again the previous May, but Flinders hoped his French

passport (though for a different vessel) and the scientific nature of

his mission would allow him to continue on his way. Despite this, and

the knowledge of Baudin's earlier encounter with Flinders, the French

governor, Charles Mathieu Isidore Decaen,

was suspicious and detained Flinders. The relationship between the men

soured: Flinders was affronted at his treatment, and Decaen insulted by

Flinders' refusal of an invitation to dine with him and his wife.

Decaen's search of Flinders' vessel uncovered a trunk full of papers

from the governor of New South Wales that were not permitted under his

scientific passport. Decaen referred the matter to the French

government, which was delayed not only by the long voyage, but also by

the general confusion of war. Eventually on 11 March 1806, Napoleon gave

his approval, but Decaen still refused to allow Flinders' release. It

has been suggested that by this stage Decaen believed Flinders'

knowledge of the island's defences would have encouraged Britain to

attempt to capture it. Nevertheless, in June 1809 the Royal Navy began

a blockade of the island, and in June 1810 Flinders was paroled. Travelling via the Cape of Good Hope, he received a promotion to Post - Captain, before continuing to England. Flinders

had been confined for the first few months of his captivity, however he

was later afforded greater freedoms to move around the island and

access his papers. In November 1804 Flinders sent the first map of the

landmass he had charted (Y46/1) back to England. This was the only map

made by Flinders, where he used the name "Australia" in all capitals for the title, and the first known time Flinders used the word "Australia". Flinders finally returned to England in October 1810 in poor health and immediately resumed work preparing "A Voyage to Terra Australis" and his Atlas of maps for publication. The full title of this book

which was first published in London in July 1814 was given, as was

common at the time, a synoptic description: "A Voyage to Terra

Australis : undertaken for the purpose of completing the discovery

of that vast country, and prosecuted in the years 1801, 1802, and 1803

in His Majesty's ship the Investigator, and subsequently in the armed

vessel Porpoise and Cumberland Schooner. With an account of the

shipwreck of the Porpoise, arrival of the Cumberland at Mauritius, and

imprisonment of the commander during six years and a half in that

island" . Original copies of the "Atlas to Flinders' Voyage to Terra

Australis" are held at the Mitchell Library in Sydney, Australia, as

a portfolio that accompanied the book and included engravings of 16

maps, and 4 plates of views, and 10 plates of Australian flora. The book was republished in 3 volumes in 1964 accompanied by a reproduction

of the portfolio. Flinders' map of Terra Australia was first published

in January 1814 and

the remaining maps where published before his atlas and book. On 19

July 1814, the day after the book and atlas was published, Matthew

Flinders died, aged 40. On 12 April 1812 he and his wife had had a daughter who became Mrs. William Petrie; in 1853 the governments of New South Wales and Victoria bequeathed

a belated pension to her (deceased) mother of £100 per year, to

go to surviving issue of the union. This she, Mrs. Anne (née

Flinders) Petrie (1812 – 1892), accepted on behalf of her young son, named William Matthew Flinders Petrie, who would go on to become an accomplished archaeologist and Egyptologist. Flinders was not the first to use the word "Australia". He owned a copy of Alexander Dalrymple's 1771 book An Historical Collection of Voyages and Discoveries in the South Pacific Ocean,

and it seems likely he borrowed it from there, but he applied it

specifically to the continent, not the whole South Pacific region. In

1804 he wrote to his brother: "I call the whole island Australia, or

Terra Australis" and later that year he wrote to Sir Joseph Banks and

mentioned "my general chart of Australia." That 92 cm x 72 cm

chart, made in 1804, was the first time Australia was used to name the

landmass we know today. A map Flinders constructed from all the

information he had accumulated while he was in Australian waters and

finished while he was detained by the French in Mauritius. Flinders

continued to promote the use of the word until his arrival in London in

1810. Here he found that Banks did not approve of the name and had not

unpacked the chart he had sent him, and that "New Holland" and "Terra

Australis" were still in general use. As a result, a book by Flinders

was published under the title A Voyage to Terra Australis despite

his objections. The final proofs were brought to him on his deathbed,

but he was unconscious. The book was published on 18 July 1814, but

Flinders did not regain consciousness and died the next day, never

knowing that his name for the continent would be later accepted. In this book, Flinders wrote: ...with the accompanying note at the bottom of the page: So Flinders had concluded that the Terra Australis, as hypothesised by Aristotle and Ptolemy (which would later be discovered as Antarctica) did not exist, therefore he wanted the name applied to Australia, and it stuck. Flinders' book was widely read and gave the term "Australia" general currency. Lachlan Macquarie, Governor of New South Wales, became aware of Flinders' preference for the name Australia and used it in his dispatches to England. On 12 December 1817 he

recommended to the Colonial Office that it be officially adopted. In

1824 the British Admiralty agreed that the continent should be known

officially as Australia. Flinders'

name is now associated with over 100 geographical features and places

in Australia in addition to Flinders Island, in Bass Strait. Flinders

is seen as being particularly important in South Australia, where he is

often considered the main explorer of the state. Landmarks named after

him in South Australia include the Flinders mountain range and Flinders Ranges National Park, Flinders Chase National Park on Kangaroo Island, Flinders University, Flinders Medical Centre, the suburb Flinders Park and Flinders Street in Adelaide. In Victoria, eponymous places include Flinders Street in Melbourne, the suburb of Flinders, the federal electorate of Flinders, and the Matthew Flinders Girls Secondary College in Geelong. Flinders Bay in Western Australia and Flinders Way in Canberra also

commemorate him. There is even a school named after him: Flinders Park

Primary School. Another school named in his honour is Matthew Flinders Anglican College, on the Sunshine Coast in Queensland. A former electoral district of the Queensland Parliament was named Flinders. There are also Flinders Highways in both Queensland and South Australia. Bass & Flinders Point in the southernmost part of Cronulla in New South Wales features a monument to George Bass and Matthew Flinders, who explored the Port Hacking estuary. Australia holds a large collection of statues erected in Flinders' honour, second only in number to statues of Queen Victoria.

In his native England the first statue of Flinders was erected on 16

March 2006 (his birthday) in his hometown of Donington. The statue also

depicts his beloved cat Trim, who accompanied him on his voyages. Flinder's

proposal for the use of iron bars to be used to compensate for the

magnetic deviations caused by iron on board a ship resulted in them

being known as Flinders bars. Flinders, who was John Franklin's uncle by marriage, instilled in him a love for navigating, and took him with him on his voyage aboard the Investigator. In 1964 he was honoured on a postage stamp issued by Australia Post, again in 1980, and in 1998 with George Bass. Flindersia is a genus of 14 species of tree in the citrus family. Named by the Investigator's botanist, Robert Brown in honour of Matthew Flinders.