<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Franz Mertens, 1840

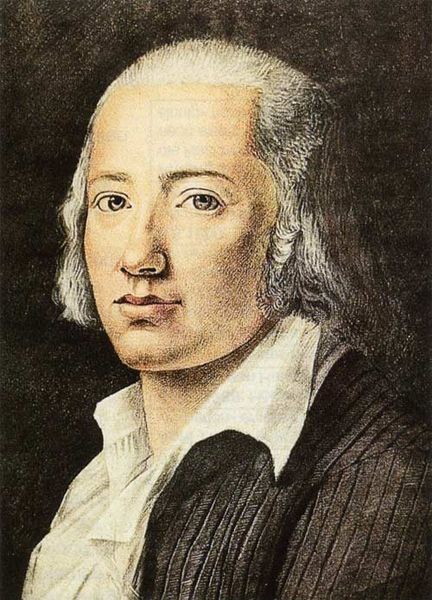

- Poet Johann Christian Friedrich Hölderlin, 1770

- General of the Imperial German Army Paul Emil von Lettow - Vorbeck, 1870

PAGE SPONSOR

Johann Christian Friedrich Hölderlin (20 March 1770 – 7 March 1843) was a major German lyric poet, commonly associated with the artistic movement known as Romanticism. Hölderlin was also an important thinker in the development of German Idealism, particularly his early association with and philosophical influence on his seminary roommates and fellow Swabians Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel and Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling.

Hölderlin was born in Lauffen am Neckar in the Duchy of Württemberg. His father, the manager of a church estate, died when the boy was two years old. He was brought up by his mother, who in 1774 married the Mayor of Nürtingen and moved there. He had a full sister, born after their father's death, and a half - brother. His stepfather died when he was nine. He went to school in Denkendorf and Maulbronn and then studied theology at the Tübinger Stift, where his fellow students included Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling (who had been a fellow pupil at his first school) and Isaac von Sinclair. It has been speculated that it was probably Hölderlin who brought to Hegel's attention the ideas of Heraclitus about the union of opposites, which the philosopher would develop into his concept of dialectics. Finding he could not sustain a Christian faith, Hölderlin declined to become a minister of religion and worked instead as a private tutor. In 1793 - 94 he met Friedrich Schiller and Johann Wolfgang Goethe and began writing his epistolary novel Hyperion. During 1795 he enrolled for a while at the University of Jena where he attended Fichte's classes and met Novalis.

As a tutor in Frankfurt from 1796 to 1798 he fell in love with Susette Gontard, the wife of his employer, the banker Jakob Gontard. The feeling was mutual, and this relationship was the most important in Hölderlin's life. Susette is addressed in his poetry under the name of 'Diotima'. Their affair was discovered and Hölderlin was harshly dismissed. He lived in Homburg from 1798 to 1800, meeting Susette in secret once a month and attempting to establish himself as a poet, but was plagued by money worries, having to accept a small allowance from his mother. He worked on a tragedy in the Greek manner, Empedokles, producing three versions, all unfinished. Already at this time he was diagnosed as suffering from a severe "hypochondria", a condition that would worsen after his last meeting with Susette Gontard in 1800. After a sojourn in Stuttgart, probably working on his translations of Pindar, at the end of 1800 he found further employment as a tutor in Hauptwyl, Switzerland, and then, in 1802, in Bordeaux, at the household of the Hamburg consul. His stay in that French city is celebrated in "Andenken" ("Remembrance"), one of his greatest poems. In a few months, however, he returned home on foot via Paris (where he saw Greek sculptures for the only time in his life). He arrived home in Nürtingen both physically and mentally exhausted. Susette died from influenza in Frankfurt about the same time.

After some time in Nürtingen he was taken to the court of Homburg by Sinclair, who found a sinecure for him as court librarian, but in 1805 Sinclair was denounced as a conspirator and tried for treason. Hölderlin was in danger of being tried too but was declared mentally unfit to stand trial. The state of Hesse - Homburg was dissolved the following year after the Battle of Jena. On 11 September Hölderlin was delivered into the clinic at Tübingen run by Dr Ferdinand Autenrieth, inventor of a mask for the prevention of screaming in the mentally ill. The clinic was attached to the University and the poet Kerner, then studying medicine, was assigned to look after Hölderlin for a while. The following year he was discharged as incurable and given three years to live, but was taken in by the carpenter Ernst Zimmer (a cultured man, who had read Hyperion) and given a room in his house in Tübingen, which had been a tower in the old city wall, with a view across the Neckar river and meadows. Zimmer and his family cared for Hölderlin until his death in 1843, 36 years later. Wilhelm Waiblinger, a young poet and admirer, left a poignant account of Hölderlin's day - to - day life during these long, empty years. Hölderlin continued to write poetry of a simplicity and formality quite unlike what he had been writing up to 1805. As time went on he became a kind of minor tourist attraction and was visited by curious travelers and autograph hunters. Often he would play the piano or spontaneously write short verses for such visitors, confining himself to conventional subjects such as Greece, the Seasons, or The Spirit of the Times, pure in versification but almost empty of affect, although a few of these (such as the famous 'The Lines of Life', Die Linien des Lebens, which he wrote out for his carer Zimmer on a piece of wood) have a piercing beauty and have been set to music by many composers.

Hölderlin's own family did nothing to support him but instead petitioned (successfully) for his upkeep to be paid by the state. His mother and sister never visited him, and his stepbrother only once. His mother died in 1828: his sister and stepbrother quarrelled over the inheritance, arguing that too large a share had been allotted to Hölderlin, and tried unsuccessfully to have the will overturned in court. Neither of them attended his funeral, nor had the (now famous) friends of his childhood, Hegel and Schelling, had anything to do with him for years; the Zimmer family were his only mourners. His inheritance, including the patrimony left him by his father when he was two, had been kept from him by his mother and was untouched and continually accruing interest. He died a rich man, and never knew it.

The poetry of Hölderlin, widely recognized today as one of the highest points of German literature, was little known or understood during his lifetime, and slipped into obscurity shortly after his death; his illness and reclusion made him fade from his contemporaries' consciousness – and, even though selections of his work were published by his friends during his lifetime, it was largely ignored for the rest of the 19th century.

Indeed, Hölderlin was a man of his time, an early supporter of the French Revolution – in his youth at the Seminary of Tübingen, he and some colleagues from a "republican club" planted a "Tree of Freedom" in the market square, prompting the Grand Duke himself to admonish the students at the seminary. In his early years he was an enthusiastic supporter of Napoleon, whom he honors in one of his couplets.

Like Goethe and Schiller, his older contemporaries, Hölderlin was a fervent admirer of ancient Greek culture, but his understanding of it was very personal. Much later, Friedrich Nietzsche would recognize in him the poet who first acknowledged the Orphic and Dionysian Greece of the mysteries, which he would fuse with the Pietism of his native Swabia in a highly original religious experience. For Hölderlin, the Greek gods were not the plaster figures of conventional classicism, but living, actual presences, wonderfully life giving though, at the same time, terrifying. He understood and sympathized with the Greek idea of the tragic fall, which he expressed movingly in the last stanza of his "Hyperions Schicksalslied" ("Hyperion's Song of Destiny").

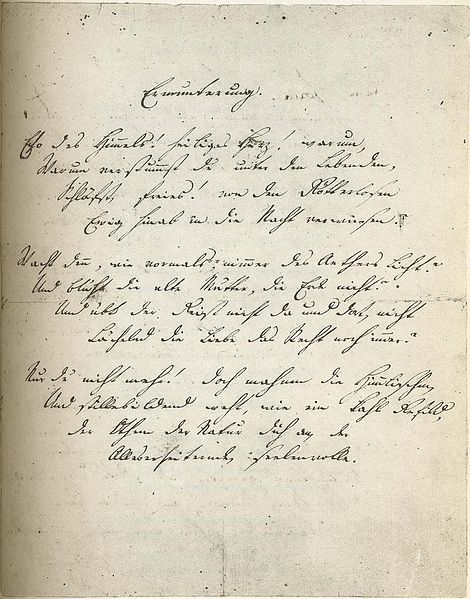

In

the great poems of his maturity, Hölderlin would generally adopt a

large scale, expansive and unrhymed style. Together with these long

hymns, odes and elegies – which included "Der Archipelagus" ("The

Archipelago"), "Brot und Wein" ("Bread and Wine") and "Patmos" – he

also cultivated a crisper, more concise manner in epigrams and

couplets, and in short poems like the famous "Hälfte des Lebens"

("The Middle of Life"). In the years after his return from Bordeaux he

completed some of his greatest poems but also, once they were finished,

returned to them repeatedly, creating new and stranger versions

sometimes in several layers on the same manuscript, which makes the

editing of his works problematic. Some of these later versions (and

some later poems) are fragmentary, but they have astonishing intensity.

He seems sometimes also to have considered the fragments, even with

gaps and unfinished lines and incomplete sentence structure, to be

poems in themselves. This obsessive revising and his stand alone

fragments were once considered evidence of his mental disorder, but

they were to prove very influential on later poets such as Paul Celan.

In his years of madness, Hölderlin would occasionally pen

ingenuous rhymed quatrains, sometimes of a childlike beauty, which he

would sign with fantastic names (most often "Scardanelli") and give

fictitious dates from the previous or future centuries. Hölderlin’s major publication in his lifetime was his novel Hyperion,

which was issued in two parts (1797 and 1799). Various individual poems

were published but attracted little attention and in 1799 he also

attempted to produce a literary philosophical periodical, Iduna. His translations of the dramas of Sophocles were

published in 1804 but were generally met with derision over their

apparent artificiality and difficulty caused by transposing Greek

idioms into German. In the 20th century, theorists of translation such as Walter Benjamin have vindicated them, showing their importance as a new – and greatly influential – model of poetic translation. Der Rhein and Patmos, two of the longest and most densely charged of the hymns, appeared in a poetic calendar in 1808. Wilhelm

Waiblinger, who visited Hölderlin in his tower repeatedly in

1822-3 and depicted him in the protagonist of his novel Phaëthon, urged the necessity of issuing an edition of his poems and the first collection of his poetry was issued by Ludwig Uhland and C.T. Schwabin

1826. They omitted anything they suspected might be 'touched by

insanity'. A copy was given to Hölderlin, but some years later

this was stolen by a souvenir hunter. A second, enlarged edition with a biographical essay appeared in 1842, the year before Hölderlin’s death. Only in 1913 did Norbert von Hellingrath, a member of the circle around poet Stefan George,

bring out the first two volumes of what eventually became a six volume

edition of Hölderlin's poems, prose and letters (the 'Berlin

Edition', Berliner Ausgabe).

For the first time, Hölderlin's hymnic drafts and fragments were

published and it became possible to gain some overview of his work in

the years between 1800 and 1807, which had been only sparsely covered

in earlier editions. The Berlin edition and von Hellingrath's

impassioned advocacy of Hölderlin's work shifted the emphasis of

appraisal from his earlier elegies to the enigmatic and grandiose later

hymns. At the same time, Hölderlin's appeals to the Germans became

all too easy to abuse among nationalists and finally among

Nazi inflected groups. Already in 1912, before the Berlin edition began to appear, Rainer Maria Rilke composed his first two Duino Elegies whose

form and spirit draw strongly on the hymns and elegies of

Hölderlin. Rilke had met von Hellingrath a few years earlier and

had seen some of the hymn drafts, and the Duino Elegies heralded

the beginning of a new appreciation of Hölderlin's late work.

Although his hymns can hardly be imitated, they have become a powerful

influence on modern poetry in German and other languages, and are

sometimes cited as the very crown of German lyric poetry. The Berlin edition was to some extent superseded by the Stuttgart Edition (Grosse Stuttgarter Ausgabe) edited by Friedrich Beissner and Adolf Beck,

which began publication in 1943 and eventually saw completion in 1986.

This undertaking was much more rigorous in textual criticism than the

Berlin edition and solved many issues of interpretation raised by

Hölderlin's unfinished and undated texts (sometimes several

versions of the same poem with major differences). Meanwhile a third

complete edition, the Frankfurt Critical Edition (Frankfurter Historisch - kritische Ausgabe), began publication in 1975 under the editorship of Dietrich Sattler;

it is still in progress. There are other editions; it should be noted

that no two of them show all the major poems in congruent textual

status. Strophes and readings are sometimes arranged in different ways

from one edition to the next. Though Hölderlin's hymnic style

– dependent as it is on a genuine belief in the divinity – creates a

deeply personal fusion of Greek mythic figures and romantic nature

mysticism, which can appear both strange and enticing, his shorter and

sometimes more fragmentary poems have exerted wide influence too on

later German poets, from Georg Trakl onwards. He also had an influence on the poetry of Hermann Hesse and Paul Celan. (Celan wrote a poem about Hölderlin, called "Tübingen, January" which ends with the word Pallaksch - according to C.T. Schwab, Hölderlin's favourite neologism "which sometimes meant Yes, sometimes No"). Hölderlin

was a poet - thinker who wrote, fragmentarily, on poetic theory and

philosophical matters. His theoretical works, such as the essays "Das

Werden im Vergehen" ("Becoming in Dissolution") and "Urteil und Sein"

("Judgement and Being") are insightful and important if somewhat

tortuous and difficult to parse. They raise many of the key problems

also addressed by his Tübingen roommates

Hegel and Schelling. And, though his poetry was never "theory - driven",

the interpretation and exegesis of some of his more difficult poems has

given rise to profound philosophical speculation by thinkers as

divergent as Martin Heidegger, Jacques Derrida, Michel Foucault and Theodor Adorno.

Hölderlin's poetry has inspired many composers. One of the earliest settings of Hölderlin's poetry and perhaps the most famous is Schicksalslied by Brahms, based on Hyperions Schicksalslied. Other composers of Hölderlin settings include Peter Cornelius, Hans Pfitzner, Richard Strauss (Drei Hymnen), Max Reger (An die Hoffnung), Alphons Diepenbrock (Die Nacht), Richard Wetz (Hyperion), Josef Matthias Hauer, Stefan Wolpe, Paul Hindemith, Benjamin Britten, Hans Werner Henze, Bruno Maderna (Hyperion, Stele an Diotima), Heinz Holliger (the Scardanelli - Zyklus), Hans Zender (Hölderlin lesen I-IV), György Kurtág (who planned an opera on Hölderlin), György Ligeti (Hölderlin - Phantasien), Hanns Eisler (Hollywood Liederbuch), Viktor Ullmann (who wrote settings in Terezin concentration camp), Wolfgang von Schweinitz, Walter Zimmermann (Hyperion, an epistolary opera) and Wolfgang Rihm. Wilhelm Killmayer based in 1986 two song cycles Hölderlin - Lieder for tenor and orchestra on Hölderlin's latest poems. Kaija Saariaho's Tag des Jahrs for mixed choir and electronics (2001) is based on four of these poems, Graham Waterhouse composed in 2003 Sechs späteste Lieder nach Hölderlin for (singing and speaking) voice and cello on six latest poems. Many songs of Swedish alternative rock band ALPHA 60 also contain lyrical references to Hölderlin's poetry. Finnish melodic death metal band Insomnium has transposed and used Hölderlin's verses in several songs.

Robert Schumann's late piano suite Gesänge der Frühe was inspired by Hölderlin, as was Luigi Nono's string quartet Fragmente - Stille, an Diotima and parts of his opera Prometeo. Josef Matthias Hauer wrote many piano pieces inspired by individual lines of the poems. Carl Orff used Hölderlin's German translations of Sophocles in his operas Antigone and Oedipus der Tyrann. Paul Hindemith's First Piano Sonata is influenced by Hölderlin's poem Der Main. Hans Werner Henze's Seventh Symphony is partly inspired by Hölderlin.