<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Jurij Bartolomej Vega, 1754

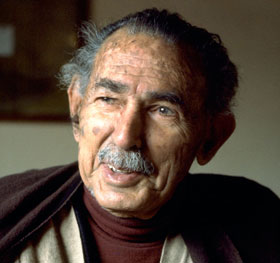

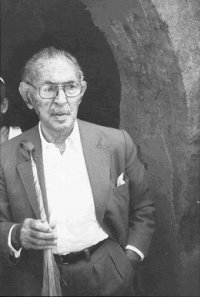

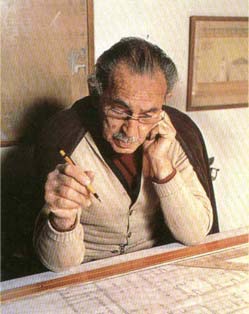

- Architect Hassan Fathy, 1900

- Prince of the Russian Empire Felix Felixovich Yusupov, 1887

PAGE SPONSOR

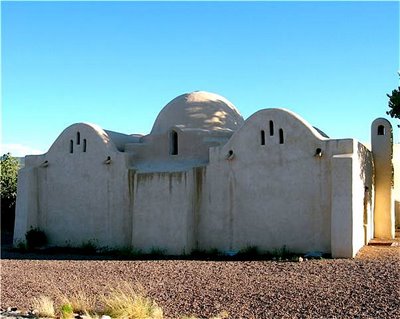

Hassan Fathy (1900 – 1989, Arabic: حسن فتحي) was a noted Egyptian architect who pioneered appropriate technology for building in Egypt, especially by working to re-establish the use of mud brick (or adobe) and traditional as opposed to western building designs and lay-outs. Fathy was recognized with the Aga Khan Award for Architecture Chairman's Award in 1980.

Hassan Fathy was born in Alexandria in 1900. He trained as an architect in Egypt, graduating in 1926 from the King Fuad University (now Cairo University).

Hassan Fathy was cosmopolitan trilingual professor - engineer - architect, amateur musician, dramatist, and inventor. He designed nearly 160 separate projects, from modest country retreats to fully planned communities with police, fire, and medical services, with markets, schools and theatres, with places for worship and others for recreation, including many, functional buildings including laundry facilities, ovens, and wells. He utilized ancient design methods and materials, and integrated a knowledge of the rural Egyptian economic situation with a wide knowledge of ancient architectural and town design techniques. He trained local inhabitants to make their own materials and build their own buildings.

He began teaching at the College of Fine Arts in 1930 and designed his first mud brick buildings in the late 1930s.

He worked on New Gourna, a town for the resettlement of Grave robbery which was designed for beauty and built with mud between 1946 and 1952. This project was noticed in Europe being applauded in a popular British weekly during 1947 and then in a British professional journal six months later; further articles were published in Spanish, French and in Dutch.

In 1953 he returned, heading the Architectural Section of the Faculty of Fine Arts, Cairo, in 1954.

Fathy's next major engagement was designing and supervising school construction for Egypt's Ministry of Education.

In 1957, frustrated with bureaucracy and convinced that buildings would speak louder than words, he moved to Athens to collaborate with international planners evolving the principles of ekistical design under the direction of Constantinos Doxiadis. He served as the advocate of traditional natural energy solutions in major community projects for Iraq, and Pakistan and undertook, under related auspices, extended travel and research for the 'Cities of the Future' program in Africa.

Returning to Cairo in 1963, he moved to Darb al-Labbana, near the Citadel, where he lived and worked for the rest of his life in the intervals between speaking and consulting engagements. As a man with a riveting message in an era searching for alternatives, in fuel, in personal interactions and in economic supports.

He moved from his first major international appearance at the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Boston in 1969, to multiple trips per year as a leading critical member of the architectural profession. His book on Gourna, published in a limited edition in 1969, became even more influential in 1973 with its new English title 'Architecture for the Poor'. His participation in the first U.N. Habitat conference in 1976 in Vancouver was followed shortly by two events that significantly shaped the rest of his activities. He began to serve on the steering committee for the nascent Aga Khan Award for Architecture and he founded and set guiding principles for his Institute of Appropriate Technology.

In 1980, he was awarded the Balzan Prize for Architecture and Urban Planning and the Right Livelihood Award.

He held several government positions and died in Cairo in 1989. Fathy is Egypt's best known architect since Imhotep. An

appreciation of the importance of Fathy's contribution to world

architecture became clear only as the twentieth century waned. Climatic conditions, public health considerations, and ancient craft skills

also affected his design decisions. Based on the structural massing of

ancient buildings, Fathy incorporated dense brick walls and traditional

courtyard forms to provide passive cooling.

Fathy married once, to Aziza Hassanein, sister of

Ahmed Pasha Hassanein.

He designed a villa for her along the Nile in Maadi, which was

destroyed to make way for the corniche. He also designed her brother's

maosoleum (1947), along Salah Salem, in neo - mameluke style. The

children of his five brothers and sisters, aware of the obligation to

preserve the heritage of their uncle tried to make sure that the

materials transmitting his ideals and his art will remain available in Egypt, for the future benefit that country.