<Back to Index>

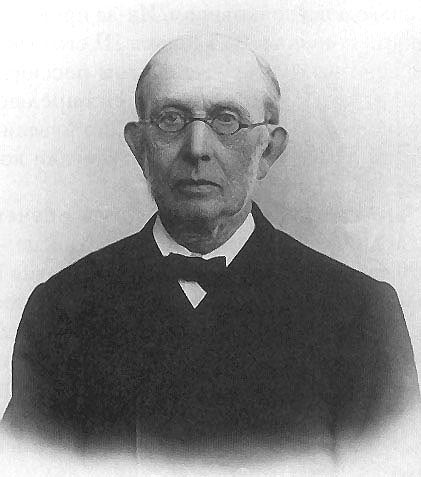

- Jurist and Statesman Konstantin Petrovich Pobedonostsev, 1827

- Poet Emile Verhaegen, 1855

- Prime Minister of France Léon Victor Auguste Bourgeois, 1851

PAGE SPONSOR

Konstantin Petrovich Pobyedonostsyev (Константин Петрович Победоносцев in Russian) (May 21, 1827 – March 23, 1907) was a Russian jurist, statesman, and adviser to three Tsars. Usually regarded as a prime representative of reactionary views and was the "éminence grise" of imperial politics during the reign of his disciple Alexander III of Russia, holding the position of the Ober - Procurator of the Holy Synod, the highest position of the supervision of the Russian Orthodox Church by the state.

Pobedonostsev's father Pyotr Vasilyevich Pobedonostsev was a Professor of literature at Moscow State University. In 1841 he placed his son, then aged 14, in the St. Petersburg School of Jurisprudence, which had been established to prepare young men for civil service. After graduation Konstantin Pobedonostsev entered public service as an official in the eighth Moscow department of the Senate. The task of the department was to resolve civil cases from guberniyas surrounding Moscow. He was promoted rapidly within the eighth department.

At the same time in 1859 Moscow State University requested him, then aged 32, to hold lectures in civil law instead of V.N. Nikolski, who had moved abroad. For the next six years Pobedonostsev was lecturing eight hours every week while continuing to work in the eighth Moscow department. From 1860 to 1865 he was professor of civil law at Moscow State University. In 1861 Alexander II invited him to instruct his son and heir Nicholas in the theory of law and administration. As a result, Pobedonostsev had to resign from Moscow State University due to lack of time.

In 1865 at the age of 38, he was elected Professor Emeritus at the university. But on April 12, 1865 his pupil Nicholas died, but Pobedonostsev was invited to teach Nicholas's brother Alexander (the future tsar Alexander III). In 1866 Pobedonostsev moved to a permanent residence in St. Petersburg. Pobedonostsev and Tsarevich Alexander remained very close for almost thirty years, from Alexander's ascension as a Tsar until his death in 1894.

In 1868, he became a senator, in 1874 – a member of the Council of the Empire, and in 1880 – chief procurator of the Holy Synod. In the latter office Pobedonostsev was de facto head of the Russian Orthodox Church, just the year before the Tsar was assassinated. During the reign of Alexander III he was one of the most influential men in the empire. He is considered the mastermind of Alexander's Manifesto of April 29, 1881, shortly after Alexander III ascended the throne after his father was assassinated.

The Manifesto proclaimed that the absolute power of the tsar in Russia was unshakable thus putting an end to Loris - Melikov's endeavours to establish a representative body in the empire. Actually, Pobedonostsev's ascension in the first days after the assassination of Alexander II resulted in subsequent resignation of Loris - Melikov and other ministers eager for liberal reforms. He always was an uncompromising conservative and never shrank from boldly expressing his staunch opinions. Consequently, in the liberal circles he was always denounced as an obscurantist, pedant, and an enemy of progress.

After the death of Alexander III, he lost much of his influence over unfortunate Tsar Nicholas II, who was assassinated with his whole family in 1918. While Nicholas II clung to his father's Russification policy and even extending it to Finland, he generally disliked the idea of systematic religious persecution, and was not wholly averse to the partial emancipation of the Russian Church from civil control.

In 1901, Nikolai Lagovski, a supporter of socialist ideas, tried to kill Pobedonostsev. He shot in the window of Pobedonostsev's office but missed. Lagovski was sentenced to 6 years of katorga.

During the revolutionary tumult, which followed the disastrous war with Japan, Pobedonostsev, being nearly 80 years of age, retired from public affairs. He died on March 23, 1907.

He was fictionalized as old senator Ableukhov in the great novel of Andrey Bely called Petersburg (1912). Arguably he was also depicted in Leo Tolstoy's Anna Karenina as Alexei Alexandrovich Karenin. Perhaps in revenge, he ordered Tolstoy's excommunication in 1901. (Tolstoy had in fact left the Russian Orthodox Church voluntarily years earlier.) Though Pobedonostsev is mostly known as statesman and thinker, his contribution to Russian civil law is

significant. He is generally regarded as one of the most educated

Russian jurists of the 19th century. His main work was the three -

volume "Course of Civil Law" (Курс гражданского права) published in

1868, 1871

and 1880 respectively. Before the 1905 October Revolution the

Course was reprinted several times with minor changes. The Course was

regarded as an outstanding guide for practising lawyers. Quotations from

the Course are reported to have been used as a ground for decisions of

the Civil Board of the Senate. The author's profound knowledge of

Russian civil law resulted in the description of many previously

insufficiently explored institutions such as communal land law. In addition, Pobedonostsev published in 1865 in Moskovskie Vedomosti several anonymous articles on the judicial reform of Alexander II. He

criticized the reform because, as he thought, Russia lacked highly

qualified judges and in that situation the creation of an independent

judicial branch was unreasonable. Pobedonostsev held the view that human nature is sinful, rejecting the Western ideals of freedom and independence as "dangerous delusions of nihilistic youth." In his "Reflections of a Russian Statesman" (1896), he

promoted autocracy and condemned elections, representation and

democracy, the jury system, the press, free education, charities, and

social reforms. Of representative government, he wrote, "It is terrible

to think of our condition if destiny had sent us the fatal gift — the

all - Russian Parliament." He also condemned Social Darwinism as erroneous generalisation of Darwin's Theory of Evolution. In the early years of the reign of Alexander II, Pobedonostsev maintained, though keeping aloof from the Slavophiles, that Western institutions were radically bad in themselves and totally inapplicable to Russia since

they had no roots in Russian history and culture and did not correspond

to the spirit of Russian people. At that period, he contributed several

papers to Alexander Herzen's radical periodical Voices from Russia. He denounced democracy as "the insupportable dictatorship of vulgar crowd". Parliamentary methods of administration, trial by jury, freedom of the press, secular education – these were among the principal objects of his aversion. He subjected all of them to a severe analysis in his Reflections of a Russian Statesman. He once stated that Russia should be "frozen in time", showing his undivided commitment to autocracy. To these dangerous products of Western rationalism he found a counterpoise in popular vis inertiae,

and in the respect of the masses for institutions developed slowly and

automatically during the past centuries of national life. In his view,

human society evolves naturally, just like a tree grows. Human mind is

not capable to perceive the logic of social development. Any attempt to

reform society is a violence and a crime. Among the practical

deductions drawn from these premises is the necessity of preserving the autocratic power, and of fostering among the people the traditional veneration for the ritual of the national Church. Spanish journalist Enrique Gomez Carrillo compared Pobedonostsev with the Grand Inquisitors of

Spain, and quoted him as saying to the later assassinated Tsar, "You

have no right to relinquish your power. You are the arm of the

(Orthodox) Church. If you become weaker, if you kneel down, then Our

Lord Jesus will be asking you for your cowardy". In the sphere of practical politics he exercised considerable influence by inspiring and encouraging the Russification policy of Alexander III, which found expression in an administrative nationalist propaganda and led to Tsarist Russia's most elaborately justified and most thoroughly carried - out programs of religious persecution, largely centered upon Russia's Jews. These policies were implemented by the "May Laws" that banned Jews from rural areas and shtetls even within Pale of Settlement. Pobedonostsev

was influential in promulgation of all anti - Jewish measures taken

during the Alexander III's administration, such as deportations of Jews

from large cities, proscriptions of property ownership in rural as well

as urban areas, enrollment quotas in public education, and the

proscription to vote in local elections. The saying

that "a third of Jews will be converted, a third will emigrate, and the

rest will die of hunger," is often attributed to Pobedonostsev. John Klier notes the dubious provenance of this quote. According

to British author Arnold White, interested in Jewish agricultural

colonisation in Argentina, who visited Pobedonostsev with credentials

from Baron de Hirsch,

Pobedonostsev said to him: "The characteristics of the Jewish race are

parasitic; for their sustenance they require the presence of another

race as "host" although they remain aloof and self - contained. Take them

from the living organism, put them on a rock, and they die. They cannot

cultivate the soil." Although

Pobedonostsev, especially during the later years of his life, was

generally detested, there was at least one man who not only shared his

views but also sympathized with him personally. It was the novelist Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoyevsky. Their correspondence is still read with the utmost interest. "I believe that he is the only man who can save Russia from the revolution", wrote the Russian novelist.