<Back to Index>

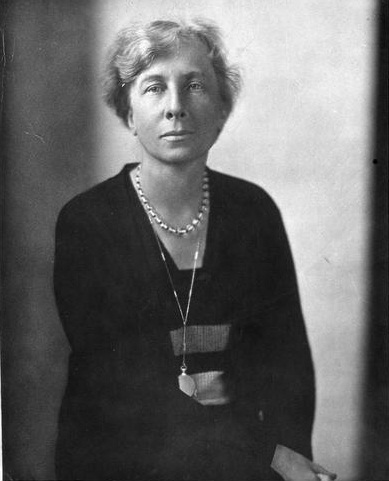

- Industrial Psychologist Lillian Moller Gilbreth, 1878

- Writer Mikhail Aleksandrovich Sholokhov, 1905

- General of the Roman Empire Germanicus Julius Caesar, 15 B.C.

PAGE SPONSOR

Lillian Moller Gilbreth (born Lillie Evelyn Moller; May 24, 1878 – January 2, 1972) was an American psychologist and industrial engineer. One of the first working female engineers holding a Ph.D., she is arguably the first true industrial / organizational psychologist. She and her husband Frank Bunker Gilbreth, Sr. were efficiency experts who contributed to the study of industrial engineering in fields such as motion study and human factors. The books Cheaper by the Dozen and Belles on Their Toes (written by their children Ernestine and Frank Jr.) are the story of their family life with their twelve children, and describe how they applied their interest in time and motion study to the organization and daily activities of such an extremely large family.

She died on January 2, 1972 in Phoenix, Arizona.

Gilbreth was born in Oakland, California. She was the second of ten children born to William Moller, a builder's supply merchant, and Annie Delger Moller, who were both of German descent. She was educated at home until she was nine years old, when her formal schooling began at a public elementary school, where she was required to start from the first grade (although she was rapidly promoted through the grades). She attended Oakland High School, where she was elected vice president of her senior class; she graduated with exemplary grades in May 1896.

Gilbreth started college at the University of California shortly after, commuting by streetcar from her parents' Oakland home. She graduated from the University of California in 1900 with a bachelor's degree in English literature and was the first female commencement speaker at the university. She originally pursued her master's degree at Columbia University, where she was exposed to the subject of psychology through courses under Edward Thorndike. However, she became ill and returned home, finishing her master's degree in literature at the University of California in 1902. Her thesis was on Ben Jonson's play Bartholomew Fair.

Gilbreth completed a dissertation and attempted to obtain a doctorate from the University of California in 1911, but was not awarded the degree due to noncompliance with residency requirements for doctoral candidates; this dissertation was later published as The Psychology of Management. Instead, since her immediate family had relocated to New England by this time, she attended Brown University and earned a Ph.D in 1915, having written a second dissertation on efficient teaching methods called "Some Aspects of Eliminating Waste in Teaching". It was the first degree granted in industrial psychology.

Lillian

Gilbreth combined the perspectives of an engineer, a psychologist, a

wife, and a mother; she helped industrial engineers see the importance

of the psychological dimensions of work. She became the first American

engineer ever to create a synthesis of psychology and scientific management.

She and her husband were certain that the revolutionary ideas of Frederick Winslow Taylor, as Taylor formulated them, would be neither easy to implement nor sufficient; their implementation would require hard work by both engineers and psychologists to make them successful. Both Lillian and Frank Gilbreth believed that scientific management as formulated by Taylor fell short when it came to managing the human element on the shop floor. The Gilbreths helped formulate a constructive critique of Taylorism; this critique had the support of other successful managers.

Her work included the marketing research for Johnson & Johnson in 1926 and her efforts to improve women’s spending decisions during the first years of the Great Depression. She also helped companies such as Johnson & Johnson and Macys with their management departments. In 1926, when Johnson & Johnson hired Lillian as a consultant to do marketing research on sanitary napkins, the firm benefited in three ways. First, it could use her training as a psychologist in measuring and the analysis of attitudes and opinions. Second, it could give her the experience of an engineer who specializes in the interaction between bodies and material objects. Third, she would be a public image as a mother and a modern career woman to build consumer trust.

She and her husband were partners in the management consulting firm of Gilbreth, Inc., which performed

time and motion study. Additionally, the Gilbreths did research on fatigue study, the forerunner to ergonomics.

Her government work began as a result of her longtime friendship with Herbert Hoover and his wife Lou Henry Hoover, both of whom she had known in California; Gilbreth had presided over the Women's Branch of the Engineers' Hoover for President campaign. At the behest of Lou Henry Hoover, Gilbreth joined the Girl Scouts as a consultant in 1929, later becoming a member of the board of directors, and remained active in the organization for more than twenty years.

Under the Hoover administration, she became the head of the women's section of the President's Emergency Committee for Employment in 1930, where she worked to gain the cooperation of women's groups for reducing unemployment. During World War II, she was an advisor to several governmental groups, providing expertise on education and labor (particularly women in the workforce) for organizations such as for the War Manpower Commission, the Office of War Information, and the United States Navy. In later years, she served on the Chemical Warfare Board and on Harry Truman's Civil Defense Advisory Council. During the Korean War, she served on the Defense Advisory Committee on Women in the Services.

Gilbreth had always been interested in teaching and education; as an undergraduate she took enough education courses to earn a teacher's certificate, and her second doctoral dissertation was on efficient teaching methods.

While residing in Providence, Rhode Island, she and husband taught free two week summer schools in scientific management from 1913 to1916. They later discussed teaching the "Gilbreth system" of motion study to members of industry, but it was not until after her husband's death that she created a formal motion study course. Her first course began in January 1925, and it offered to "prepare a member of an organization, who has adequate training both in scientific method and in plant problems, to take charge of Motion Study work in that organization." Coursework included laboratory projects and field trips to private firms to witness the application of scientific management. She ran a total of seven motion study courses out of her home in Montclair, New Jersey, until 1930.

Meanwhile, Gilbreth had been lecturing at Purdue University since 1925, where her husband had previously given annual lectures. This led to a visiting professorship in 1935, when she became the first female engineering professor at Purdue; she was granted full professorship in 1940, dividing her time between the departments of industrial engineering, industrial psychology, home economics, and the dean's office where she consulted on careers for women. In the School of Industrial Engineering, she help establish a time and motion study laboratory, and transferred motion study techniques to the home economics department under the banner of "work simplification". She retired from Purdue in 1948.

Besides teaching at Purdue, she was also appointed Knapp Visiting Professor at the University of Wisconsin's School of Engineering, and taught at other universities including the Newark College of Engineering, Bryn Mawr College, and Rutgers University. She became resident lecturer at Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1964, at the age of 86.

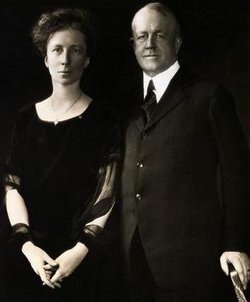

Lillian first met her future husband Frank Bunker Gilbreth, Sr. in June 1903 in Boston, Massachusetts, en route to Europe with her chaperone, who was Frank's cousin. The couple married on October 19, 1904, in Oakland, California. As planned, they became the parents of twelve children, eleven of whom lived to adulthood.

During her career, Gilbreth received numerous awards and honors, including 23 honorary degrees from such schools as Princeton University, Brown University, and the University of Michigan. She was named 1954 Alumna of the Year by the University of California's alumni association. She was accepted to the membership of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers in 1926, becoming its second female member; the society later awarded both her and her husband (posthumously) the Henry Laurence Gantt Medal in 1944 for her contributions to industrial engineering. In 1950, she was the first honorary member of the newly created Society of Women Engineers.

In 1965, she became the first woman elected to the National Academy of Engineering. The next year, she received the Hoover Medal, an engineering prize awarded jointly by five engineering societies, for her "contributions to motion study and to recognition of the principle that management engineering and human relations are intertwined.... Additionally, her unselfish application of energy and creative efforts in modifying industrial and home environments for the handicapped has resulted in full employment of their capabilities and elevation of their self - esteem".

In 1984, the United States Postal Service issued a 40˘ Great Americans series postage stamp in Gilbreth's honor, and she was lauded by the American Psychological Association as the first psychologist to be so commemorated. (Psychologists Gary Brucato Jr. and John D. Hogan later questioned this claim, noting that John Dewey had appeared on an American stamp 17 years earlier. However, they also emphasized that Gilbreth was the first female psychologist to do so.) A comprehensive international list of psychologists on stamps (compiled by psychology historian Ludy T. Benjamin) indicates that Gilbreth was only the second female psychologist commemorated by a postage stamp in all the world, preceded only by Maria Montessori in India in 1970.

Multiple engineering awards have been named in her honor. The Lilian M. Gilbreth Lectureships were established in 2001 by the National Academy of Engineering, to recognize outstanding young American engineers, while the highest honor bestowed by the Institute of Industrial Engineers is the Frank and Lillian Gilbreth Industrial Engineering Award, for "those who have distinguished themselves through contributions to the welfare of mankind in the field of industrial engineering". At Purdue University, the Lilian M. Gilbreth Distinguished Professor is an honor bestowed on a member of the industrial engineering department. Additionally, the Society of Women Engineers awards the Lillian Moller Gilbreth Memorial Scholarship to deserving female engineering undergraduates.

Lillian and husband Frank have a permanent collection in the Smithsonian National Museum of American History, and her portrait hangs in the National Portrait Gallery. Their papers are housed in The Frank and Lillian Gilbreth Library of Management at Purdue University.