<Back to Index>

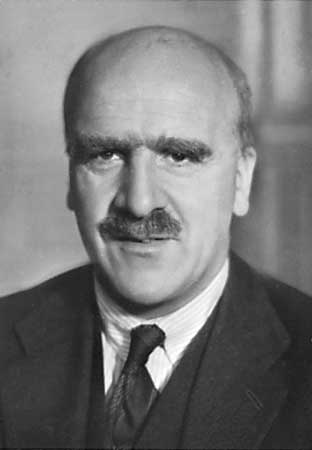

- Biologist John Burdon Sanderson Haldane, 1892

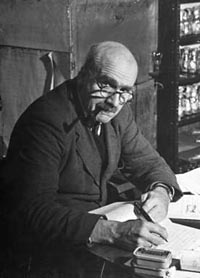

- Painter Philip de Koninck, 1619

- Brevet Major General of the U.S. Army William Woods Averell, 1832

PAGE SPONSOR

John Burdon Sanderson Haldane FRS (5 November 1892 – 1 December 1964), known as Jack (but who used 'J.B.S.' in his printed works), was a British born Indian geneticist and evolutionary biologist. He was one of the founders (along with Ronald Fisher and Sewall Wright) of population genetics.

Haldane was born in Oxford to physiologist John Scott Haldane and Louisa Kathleen Haldane (née Trotter), and descended from an aristocratic intellectual Scottish family. His younger sister, Naomi, became a writer. His uncle was Richard Haldane, 1st Viscount Haldane, politician and one time Secretary of State for War; his aunt was the author Elizabeth Haldane. His father was a scientist, a philosopher and a Liberal, and his mother was a Conservative. Haldane took interest in his father’s work very early in his childhood. It was the result of this lifelong study of the natural world and his devotion to empirical evidence that he felt atheism was the only rational deduction available in light of all evidence saying, "My practice as a scientist is atheistic. That is to say, when I set up an experiment I assume no god, angel or devil is going to interfere with its course... I should therefore be intellectually dishonest if I were not also atheistic in the affairs of the world."

Haldane was educated at Eton and New College, Oxford. He served in the British Army during the First World War in the Black Watch regiment.

Between 1919 and 1922 he was a Fellow of New College, Oxford, then moved to Cambridge University, where he accepted a Readership in Biochemistry at Trinity College and taught there until 1932. During his nine years at Cambridge, Haldane worked on enzymes and genetics, particularly the mathematical side of genetics. Haldane wrote many popular essays on science that were eventually collected and published in 1927 in a volume entitled Possible Worlds. He then accepted a position as Professor of Genetics and moved to University College London where he spent most of his academic career. Four years later he became the first Weldon Professor of Biometry at University College London. In 1923, in a talk given in Cambridge, Haldane, foreseeing the exhaustion of coal for power generation in Britain, proposed a network of hydrogen - generating windmills. This is the first proposal of the hydrogen based renewable energy economy.

In 1925, G.E. Briggs and Haldane derived a new interpretation of the enzyme kinetics law described by Victor Henri in 1903, different from the 1913 Michaelis – Menten equation. Leonor Michaelis and Maud Menten assumed that enzyme (catalyst) and substrate (reactant) are in fast equilibrium with their complex, which then dissociates to yield product and free enzyme. The Briggs – Haldane equation was of the same algebraic form, but their derivation is based on the quasi steady state approximation, that is the concentration of intermediate complex (or complexes) does not change. As a result, the microscopic meaning of the "Michaelis Constant" (Km) is different. Although commonly referring it as Michaelis – Menten kinetics, most of the current models actually use the Briggs – Haldane derivation.

Haldane made many contributions to human genetics and was one of the three major figures to develop the mathematical theory of population genetics. He is usually regarded as the third of these in importance, after R.A. Fisher and Sewall Wright. His greatest contribution was in a series of ten papers on "A Mathematical Theory of Natural and Artificial Selection" which was the major series of papers on the mathematical theory of natural selection. It treated many major cases for the first time, showing the direction and rates of changes of gene frequencies. It also pioneered in investigating the interaction of natural selection with mutation and with migration. Haldane's book, The Causes of Evolution (1932), summarized these results, especially in its extensive appendix. This body of work was a component of what came to be known as the "modern evolutionary synthesis", re-establishing natural selection as the premier mechanism of evolution by explaining it in terms of the mathematical consequences of Mendelian genetics.

Haldane introduced many quantitative approaches in biology such as in his essay On Being the Right Size. His contributions to theoretical population genetics and statistical human genetics included the first methods using maximum likelihood for estimation of human linkage maps, and pioneering methods for estimating human mutation rates. His was the first to calculate the mutational load caused by recurring mutations at a gene locus, and to introduce the idea of a "cost of natural selection".

Haldane is also known for an observation from his essay, On Being the Right Size, which Jane Jacobs and others have since referred to as Haldane's principle. This is that sheer size very often defines what bodily equipment an animal must have: "Insects, being so small, do not have oxygen carrying bloodstreams. What little oxygen their cells require can be absorbed by simple diffusion of air through their bodies. But being larger means an animal must take on complicated oxygen pumping and distributing systems to reach all the cells." The conceptual metaphor to animal body complexity has been of use in energy economics and secession ideas.

Haldane was a keen experimenter, willing to expose himself to danger to obtain data. One experiment involving elevated levels of oxygen saturation triggered a fit which resulted in him suffering crushed vertebrae. In his decompression chamber experiments, he and his volunteers suffered perforated eardrums, but, as Haldane stated in What is Life, "the drum generally heals up; and if a hole remains in it, although one is somewhat deaf, one can blow tobacco smoke out of the ear in question, which is a social accomplishment."

In 1952, he received the Darwin Medal from the Royal Society. In 1956, he was awarded the Huxley Memorial Medal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. Among other awards, he received the Feltrinelli Prize, an Honorary Doctorate of Science, an Honorary Fellowship at New College, and the Kimber Award of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences. He was awarded the Linnean Society of London's prestigious Darwin – Wallace Medal in 1958.

In 1924, Haldane met Charlotte Burghes (née Franken), a young reporter for the Daily Express.

So that they could marry, Charlotte divorced her husband Jack Burghes,

causing some controversy. Haldane was almost dismissed from Cambridge

for the way he handled his meeting with her, which led to the divorce.

They married in 1926. Following separation in 1942, the Haldanes

divorced in 1945. He later married Helen Spurway.

Haldane became a socialist during World War I, supported the Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War, and finally became a Communist. He was an enthusiastic, idealistic Marxist, and wrote many articles in the Communist Daily Worker. He was the chairman of the editorial board of the London edition for several years. His vision of the Socialist principle can be considered pragmatic. In On Being the Right Size, Haldane doubted that socialism could be operated on the scale of the British Empire or the United States or, implicitly, the Soviet Union: "while nationalization of certain industries is an obvious possibility in the largest of states, I find it no easier to picture a completely socialized British Empire or United States than an elephant turning somersaults or a hippopotamus jumping a hedge."

In 1937, Haldane became a Marxist and an open supporter of the Communist Party although not a member of the party. In 1938, he proclaimed enthusiastically that "I think that Marxism is true." He joined the Communist Party of Great Britain in 1942. The first edition of his children's book My Friend Mr. Leakey contained an avowal of his Party membership which was removed from later editions. Events in the Soviet Union, such as the rise of anti - Mendelian agronomist Trofim Lysenko and the crimes of Joseph Stalin, may have caused him to break with the Party later in life, although he showed a partial support of Lysenko and Stalin. Pressed to speak out about the rise of Lysenkoism and the persecution of geneticists in the Soviet Union as anti - Darwinist and the denouncement of genetics as incompatible with dialectical materialism, Haldane shifted the focus to the United Kingdom and a criticism of the dependence of scientific research on financial patronage. In 1941, Haldane wrote about the Soviet trial of his friend and fellow geneticist Nikolai Vavilov:

"The controversy among Soviet geneticists has been largely one between the academic scientist, represented by Vavilov and interested primarily in the collection of facts, and the man who wants results, represented by Lysenko. It has been conducted not with venom, but in a friendly spirit. Lysenko said (in the October discussions of 1939): 'The important thing is not to dispute; let us work in a friendly manner on a plan elaborated scientifically. Let us take up definite problems, receive assignments from the People's Commissariat of Agriculture of the USSR and fulfil them scientifically. Soviet genetics, as a whole, is a successful attempt at synthesis of these two contrasted points of view.'"

His ambiguous attitude toward the persecution of Vavilov was explainable by the atmosphere of the period, where the involvement in the Communist movement needed an all - or - nothing stand. His attitude changed dramatically at the end of World War II, when Lysenkoism reached a totalitarian influence in the Communist movement. He then become an explicit critic of the regime. He left the Party in 1950, shortly after considering standing for Parliament as a Communist Party candidate. He continued to admire Stalin, describing him in 1962 as "a very great man who did a very good job."

In 1956, Haldane left his post at University College London, and moved to Calcutta, where he joined the Indian Statistical Institute (ISI). Haldane's move to India was influenced by a number of factors. Officially he stated that his chief political reason was in response to the Suez Crisis.

He wrote: "Finally, I am going to India because I consider that recent

acts of the British Government have been violations of international

law." His interest in India was also because of his interest in

biological research, belief that the warm climate would do him good and

that India offered him freedom and shared socialist dreams since India

was his home country.

At the ISI, he headed the biometry unit and spent time researching a range of topics and guiding other researchers around him. He was keenly interested in inexpensive research and he wrote to Julian Huxley about his observations on Vanellus malabaricus boasting that he made them from the comfort of his backyard. Haldane took an interest in anthropology, human genetics and botany. He advocated the use of Vigna sinensis (cowpea) as a model for studying plant genetics. He took an interest in the pollination of the common weed Lantana camara. The quantitative study of biology was his main focus and he lamented that Indian universities forced those who took up biology to give up on an education in mathematics. Haldane took an interest in the study of floral symmetry. His wife, Helen Spurway, conducted studies on wild silk moths. Unable to get along with the director, P.C. Mahalanobis, Haldane resigned in February 1961 and moved to a newly established biometry unit in Orissa.

Haldane eventually became an Indian citizen. He was also interested in Hinduism and after his arrival he became a vegetarian and started wearing Indian clothes. In Kolkata, the busy connecting road from Eastern Metropolitan Bypass to Park Circus area on which the Science City is located, is named after him. In 1961, Haldane described India as "the closest approximation to the Free World." His American friend, Jerzy Neyman, a professor of Statistics in the University of California, Berkeley, objected to this premise. Neyman gave his impression that "India has its fair share of scoundrels and a tremendous amount of poor unthinking and disgustingly subservient individuals who are not attractive." Haldane retorted:

Perhaps one is freer to be a scoundrel in India than elsewhere. So one was in the U.S.A in the days of people like Jay Gould, when (in my opinion) there was more internal freedom in the U.S.A than there is today. The "disgusting subservience" of the others has its limits. The people of Calcutta riot, upset trams, and refuse to obey police regulations, in a manner which would have delighted Jefferson. I don't think their activities are very efficient, but that is not the question at issue.

When on June 25, 1962, six years after Haldane's move to India, he was described in print as a "Citizen of the World" by an American science writer named Geoff Conklin, Haldane's response was as follows:

No doubt I am in some sense a citizen of the world. But I believe with Thomas Jefferson that one of the chief duties of a citizen is to be a nuisance to the government of his state. As there is no world state, I cannot do this. On the other hand, I can be, and am, a nuisance to the government of India, which has the merit of permitting a good deal of criticism, though it reacts to it rather slowly. I also happen to be proud of being a citizen of India, which is a lot more diverse than Europe, let alone the U.S.A, U.S.S.R or China, and thus a better model for a possible world organisation. It may of course break up, but it is a wonderful experiment. So, I want to be labeled as a citizen of India.

Haldane was a famous science populariser. His essay, Daedalus; or, Science and the Future (1924), was remarkable in predicting many scientific advances but has been criticised for presenting a too idealistic view of scientific progress. Haldane’s book shows the effect of the separation between sexual life and pregnancy as a satisfactory one on human psychology and social life. The book was regarded as shocking science fiction at the time, being the first book about ectogenesis (the development of foetuses in artificial wombs) - "test tube babies", brought to life without sexual intercourse or pregnancy. His book, A.R.P. (Air Raid Precautions) (1938) combined his physiological research into the effects of stress upon the human body with his experience of air raids during the Spanish Civil War to provide a scientific explanation of the air raids that Britain was to endure during the Second World War, then imminent.

Haldane was a friend of the author Aldous Huxley, who parodied him in the novel Antic Hay (1923) as Shearwater, "the biologist too absorbed in his experiments to notice his friends bedding his wife". Haldane's discourse in Daedalus on ectogenesis was an influence on Huxley's Brave New World (1932) which features a eugenic society.

Haldane was one of those, along with Olaf Stapledon, Charles Kay Ogden, I.A. Richards, and H.G. Wells, whom C.S. Lewis accused of scientism, "the belief that the supreme moral end is the perpetuation of our own species, and that this is to be pursued even if, in the process of being fitted for survival, our species has to be stripped of all those things for which we value it — of pity, of happiness, and of freedom." Shortly after the third book of the Ransom Trilogy appeared, J.B.S. Haldane criticised all three of them in an article entitled "Auld Hornie, F.R.S.". The title reflects the sarcastic tone of the article, Auld Hornie being the pet name given to the devil by the Scots and F.R.S. standing for "Fellow of the Royal Society". Lewis’s response, "A Reply to Professor Haldane", was never published during his lifetime and apparently never seen by Haldane. In it, Lewis claims that he was attacking scientism, not scientists, by challenging the view of some that the supreme goal of our species is to perpetuate itself at any expense.

Haldane wrote a popular book for children titled My Friend Mr Leakey (first

published in 1937) which contained the stories "A Meal With a

Magician", "A Day in the Life of a Magician", "Mr Leakey's Party",

"Rats", "The Snake with the Golden Teeth", and "My Magic Collar Stud".

It was reprinted several times – in 1944, 1971, and 1972 with

illustrations by Quentin Blake. When he appears as a character in the

stories, several of which are written in the first person, he describes

his job as a professor, or: "Doing sums to make new kinds of primroses

and cats".

Shortly before his death from cancer, Haldane wrote a comic poem while in the hospital, mocking his own incurable disease; it was read by his friends, who appreciated the consistent irreverence with which Haldane had lived his productive life:

"Cancer’s a Funny Thing:

I wish I had the voice of Homer

To sing of rectal carcinoma,

This kills a lot more chaps, in fact,

Than were bumped off when Troy was sacked..."

The poem ends:

"...I know that cancer often kills,

But so do cars and sleeping pills;

And it can hurt one till one sweats,

So can bad teeth and unpaid debts.

A spot of laughter, I am sure,

Often accelerates one’s cure;

So let us patients do our bit

To help the surgeons make us fit."

Haldane died on 1 December 1964. He willed that his body be used for study at the Rangaraya Medical College, Kakinada.

"My body has been used for both purposes during my lifetime and after my death, whether I continue to exist or not, I shall have no further use for it, and desire that it shall be used by others. Its refrigeration, if this is possible, should be a first charge on my estate."

- He is famous for the (apocryphal) response that he gave when some theologians asked him what could be inferred about the mind of the Creator from the works of His Creation: "An inordinate fondness for beetles." This is in reference to there being over 400,000 known species of beetles in the world, and that this represents 40% of all known insect species (at the time of the statement, it was over half of all known insect species).

- Often quoted for saying, "My own suspicion is that the universe is not only queerer than we suppose, but queerer than we can suppose."

- "It seems to me immensely unlikely that mind is a mere by-product of matter. For if my mental processes are determined wholly by the motions of atoms in my brain I have no reason to suppose that my beliefs are true. They may be sound chemically, but that does not make them sound logically. And hence I have no reason for supposing my brain to be composed of atoms."

- "Teleology is like a mistress to a biologist: he cannot live without her but he's unwilling to be seen with her in public."

- "I had [gastritis] for about fifteen years until I read Lenin and other writers, who showed me what was wrong with our society and how to cure it...Since then I have needed no magnesia."

- "Theories have four stages of acceptance. i) this is worthless nonsense; ii) this is an interesting, but perverse, point of view, iii) this is true, but quite unimportant; iv) I always said so."

- In 1927, he predicted that no landings on Mars would be possible until 10,000,000.