<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Elwin Bruno Christoffel, 1829

- Poet and Jurist Jacob Cats, 1577

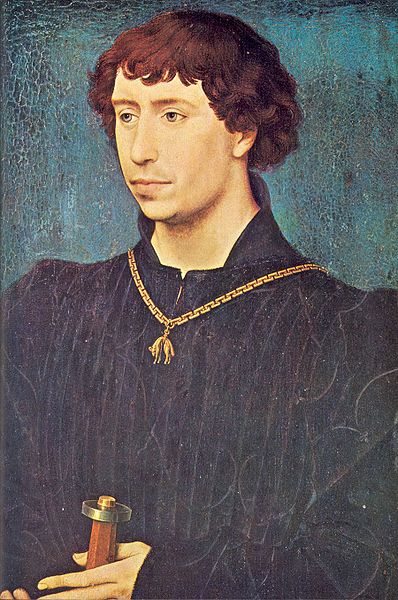

- Duke of Burgundy Charles the Bold, 1433

PAGE SPONSOR

Charles the Bold (or Charles the Rash) (French: Charles le Téméraire) (10 November 1433 – 5 January 1477), baptised Charles Martin, was Duke of Burgundy from 1467 to 1477. Known as Charles the Terrible to his enemies, he was the last Valois Duke of Burgundy and his early death was a pivotal, if under - recognised, moment in European history.

After

his death, his domains began an inevitable slide towards division

between France and the Habsburgs (who through marriage to his heiress Mary of Burgundy became

his heirs). Neither side was satisfied with the results and the

disintegration of the Burgundian state was a factor in most major wars

in Western Europe for over two centuries.

Charles the Bold was born in Dijon, the son of Philip the Good and Isabel of Portugal. In his father's lifetime (1433 – 1467) he bore the title of Count of Charolais; afterwards, he assumed all of his father's titles, including that of "Grand Duke of the West". He was also made a Knight of the Golden Fleece just twenty days after his birth, being invested by Charles I, Count of Nevers and the seigneur de Croÿ.

He was brought up under the direction of the Seigneur d'Auxy,

and early showed great application to study and also to warlike

exercises. His father's court was the most extravagant in Europe at the

time, and a centre for arts and commerce. While he was growing up,

Charles witnessed his father's efforts to unite his increasing dominions

in a single state, and his own later efforts centered on continuing and

securing his father's successes.

In 1440, at the age of seven, Charles was married to Catherine, daughter of Charles VII, the King of France, and sister of the Dauphin (afterwards Louis XI). She was only five years older than her husband, and she died in 1446 at the age of 18. They had no children.

In 1454, at the age of 21, having been a widower for eight years, Charles married a second time. He wanted to marry a daughter of his distant cousin, the Duke of York (sister of Kings Edward IV and Richard III of England), but under the Treaty of Arras (1435), he was required to marry only a royal princess of France. His father chose Isabella of Bourbon for him: she was the daughter of Philip the Good's sister, and a very distant cousin of Charles VII of France. Their daughter, Mary, was Charles' only surviving child, and became heiress to all of the Burgundian domains. Isabella died in 1465.

Charles was on familiar terms with his brother - in - law, the Dauphin, when the latter was a refugee at the Court of Burgundy from 1456 until Louis succeeded his father as King of France in 1461. But Louis began to pursue some of the same policies as his father; Charles viewed with chagrin Louis's later repurchase of the towns on the Somme, which Louis's father had ceded in 1435 to Charles's father in the Treaty of Arras. When his own father's failing health enabled him to take into his hands the reins of government (which Philip relinquished to him completely by an act of 12 April 1465), he entered upon his lifelong struggle against Louis XI, and became one of the principal leaders of the League of the Public Weal.

For his third wife, Charles was offered the hand of Louis XI's daughter, Anne; however, the wife he ultimately chose was Margaret of York (who was his second cousin, they both being descended from John of Gaunt).

With his father gone, and being no longer bound by the Treaty of Arras,

Charles decided to ally himself with Burgundy's old ally England. Louis

did his best to prevent or delay the marriage (even sending French

ships to waylay Margaret as she sailed to Sluys), but in the summer of

1468 it was celebrated sumptuously at Bruges, and Charles was made a Knight of the Garter. The couple had no

children, but Margaret devoted herself to her stepdaughter Mary; and

after Mary's death many years later, she kept Mary's two infant children

as long as she was allowed. Margaret survived her husband, and was the

only one of his wives to be Duchess of Burgundy, the first two wives

having died while Philip, Duke of Burgundy, was still alive, and thus

being known as Countesses of Charolais.

On 12 April 1465, Philip relinquished government to Charles, who spent the next summer prosecuting the War of the Public Weal against Louis XI. Charles was left master of the field at the Battle of Montlhéry (13 July 1465), where he was wounded, but this neither prevented the King from re-entering Paris nor assured Charles a decisive victory. He succeeded, however, in forcing upon Louis the Treaty of Conflans (4 October 1465), by which the King restored to him the towns on the Somme, the counties of Boulogne and Guînes, and various other small territories. During the negotiations for the Treaty, his wife Isabella died suddenly at Les Quesnoy on 25 September, making a political marriage suddenly possible. As part of the treaty Louis promised him the hand of his infant daughter Anne, with Champagne and Ponthieu as dowry, but no marriage took place.

In the meanwhile, Charles obtained the surrender of Ponthieu. The revolt of Liège against his father and his brother in law, Louis of Bourbon, the Prince - Bishop of Liège, and a desire to punish the town of Dinant,

intervened to divert his attention from the affairs of France. During

the previous summer's wars, Dinant had celebrated a false rumour that

Charles had been defeated at Montlhéry by burning him in effigy,

and chanting that he was the bastard of Duchess Isabel and John of

Heinsburg, the previous Bishop of Liege (d. 1455). On 25 August 1466,

Charles marched into Dinant, determined to avenge this slur on the

honour of his mother, and sacked the city, killing every man, woman and

child within; perhaps not surprisingly, he also successfully negotiated

at the same time with the Bishopric of Liège.

After the death of his father, Philip the Good (15 June 1467), the

Bishopric of Liège renewed hostilities, but Charles defeated them

at Sint - Truiden, and made a victorious entry into Liège, whose walls he dismantled and deprived the city of some of its privileges.

Alarmed by these early successes of the new Duke of Burgundy, and anxious to settle various questions relating to the execution of the treaty of Conflans, Louis requested a meeting with Charles and daringly placed himself in his hands at Péronne. In the course of the negotiations the Duke was informed of a fresh revolt of the Bishopric of Liège secretly fomented by Louis. After deliberating for four days how to deal with his adversary, who had thus maladroitly placed himself at his mercy, Charles decided to respect the parole he had given and to negotiate with Louis (October 1468), at the same time forcing him to assist in quelling the revolt. The town was carried by assault and the inhabitants were massacred, Louis not intervening on behalf of his former allies.

At the expiry of the one year's truce which followed the Treaty of Péronne, the King accused Charles of treason, cited him to appear before the parlement, and seized some of the towns on the Somme (1471). The Duke retaliated by invading France with a large army, taking possession of Nesle and massacring its inhabitants. He failed, however, in an attack on Beauvais, and had to content himself with ravaging the country as far as Rouen, eventually retiring without having attained any useful result.

Other

matters, moreover, engaged his attention. Relinquishing, if not the

stately magnificence, at least some of the extravagance which had

characterized the court of Burgundy under his father, he had bent all

his efforts towards the development of his military and political power.

Since the beginning of his reign he had employed himself in

reorganizing his army and the administration of his territories. While

retaining the principles of feudal recruiting, he had endeavoured to

establish a system of rigid discipline among his troops, which he had

strengthened by taking into his pay foreign mercenaries, particularly Englishmen and Italians, and by developing his artillery.

Furthermore, he had lost no opportunity to extend his power. In 1469, the Archduke of Austria, Sigismund, had sold him the county of Ferrette, the Landgraviate of Alsace, and some other towns, reserving to himself the right to repurchase.

In October 1470, his brother in law, Edward IV of England, the King of England, and many Yorkist followers, took refuge in the Burgundian Court while the deposed Henry VI was placed back on the throne in the Readeption of Henry VI.

The following March, with Burgundian support, Edward landed back in

England and by May had reclaimed the crown. In 1472 - 1473, Charles bought

the reversion of the Duchy of Guelders (i.e. the right to succeed to it) from its old Duke, Arnold,

whom he had supported against the rebellion of his son. Not content

with being "the Grand Duke of the West," he conceived the project of

forming a kingdom of Burgundy or Arles with himself as independent

sovereign, and even persuaded the Emperor Frederick to assent to crown him king at Trier.

The ceremony, however, did not take place owing to the Emperor's

precipitate flight by night (September 1473), occasioned by his

displeasure at the Duke's attitude. At the close of 1473, his duchy of

Burgundy was anchored in France and extended to the edges of the

Netherlands. Charles the Bold was now one of the wealthiest and most

powerful nobles in Europe. His fortunes and landholdings rivaled those

of many of the royal families.

In

the following year Charles involved himself in a series of difficulties

and struggles which ultimately brought about his downfall. He embroiled himself successively with the Archduke Sigismund of Austria, to whom he refused to restore his possessions in Alsace for the stipulated sum; with the Swiss, who supported the free towns of Upper Rhine in their revolt against the tyranny of the ducal governor, Peter von Hagenbach (who was condemned by a special international tribunal and executed on 9 May 1474); and finally, with René II, Duke of Lorraine, with whom he disputed the succession of Lorraine, the possession of which had united the two principal portions of Charles's territories — Flanders and the Low Countries and the Duchy and County of Burgundy.

All these enemies, incited and supported as they were by Louis, were

not long in joining forces against their common adversary.

Charles suffered a first rebuff in endeavouring to protect his kinsman, Rupprecht of the Palatinate, Archbishop of Cologne, against his rebel subjects. He spent ten months (July 1474 – June 1475) besieging the little town of Neuss on the Rhine (the Siege of Neuss), but was compelled by the approach of a powerful imperial army to raise the siege. Moreover, the expedition he had persuaded his brother - in - law, Edward IV of England, to undertake against Louis was stopped by the Treaty of Picquigny (29 August 1475). He was more successful in Lorraine, where he seized Nancy (30 November 1475).

From Nancy he marched against the Swiss, hanging or drowning the garrison of Grandson, a possession of the Savoyard Jacques de Romont, a close ally of Charles, which the Confederates had invested shortly before, and in spite of their capitulation. Some days later, however, he was attacked before Grandson by the confederate army in the Battle of Grandson and suffered a shameful defeat, being compelled to flee with a handful of attendants, and leaving his artillery and an immense booty (including his silver bath) in the hands of the allies (2 March 1476).

He succeeded in raising a fresh army of 30,000 men, with which he attacked Morat, but he was again defeated by the Swiss army, assisted by the cavalry of René II, Duke of Lorraine (22

June 1476). On this occasion, and unlike the debacle at Grandson,

little booty was lost, but Charles certainly lost about one third of his

entire army, the unfortunate losers being pushed into the nearby lake

where they were drowned or shot at while trying to swim to safety on the

opposite shore. On 6 October Charles lost Nancy, which René

re-entered.

Making a last effort, Charles formed a new army and arrived in the depth of winter before the walls of Nancy. Having lost many of his troops through the severe cold, it was with only a few thousand men that he met the joint forces of the Lorrainers and the Swiss, who had come to the relief of the town, at the Battle of Nancy (5 January 1477). He himself perished in the fight, his naked and disfigured body being discovered some days afterward frozen into the nearby river. Charles' head had been cleft in two by a halberd, multiple lances were lodged in his stomach and loins, and his face had been so badly mutilated by wild animals that only his physician was able to identify him by his long fingernails and the old battle scars on his body.

Charles' battered body was initially buried in Nancy, but in 1550 his great grandson, the Emperor Charles V, ordered it to be moved to the Church of Our Lady in Bruges, next to that of his daughter Mary. In 1562 Philip II of Spain erected a splendid mausoleum in early renaissance style over his tomb, still extant. Excavations in 1979 positively identified the remains of Mary, in a lead coffin, but those of Charles were never found.

Charles left his unmarried nineteen year old daughter, Mary of Burgundy, as his heir; clearly her marriage would have enormous implications for the political balance of Europe. Both Louis and the Emperor had unmarried eldest sons; Charles had made some movements towards arranging a marriage between the Emperor's son, Maximilian, before his own death. Louis unwisely concentrated on seizing militarily the border territories, in particular the Duchy of Burgundy (a French fief). This naturally made negotiations for a marriage difficult. He later admitted to his councillor Philippe de Commynes that this was his greatest mistake. In the meantime the Habsburg Emperor moved faster and more purposefully and secured the match for his son, the future Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor, with the aid of Mary's stepmother, Margaret.

In

view of Charles' irrational behaviour in the last year or so of his

life, it has even been suggested that he became mentally unstable.