<Back to Index>

- Physicist Ernest Thomas Sinton Walton, 1903

- Painter Alexander Maxovich Shilov, 1943

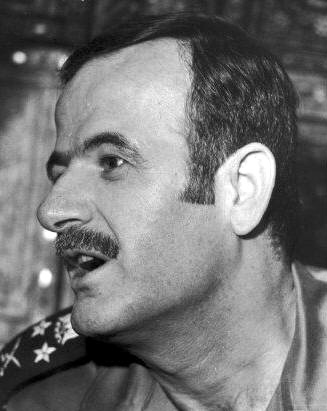

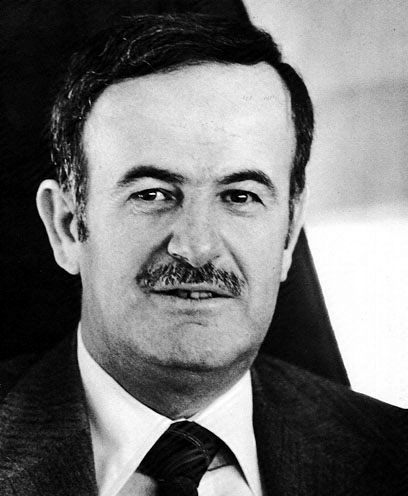

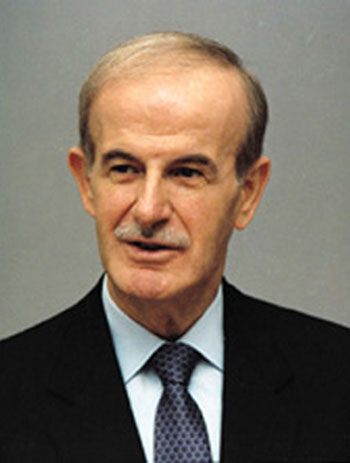

- Dictator of Syria Hafez al-Assad, 1930

PAGE SPONSOR

Hafez al-Assad (Arabic: حافظ الأسد Ḥāfiẓ al-Asad, 6 October 1930 – 10 June 2000) was the President of Syria for three decades. Assad's rule was praised for consolidating the power of the central government after decades of coups and counter - coups, such as Operation Wappen in 1957 conducted by the Eisenhower administration and preceding covert failures, and continued foreign meddling thereafter. His rule brought modern changes, including the 1973 constitution which guaranteed women's equal status in society. Assad attempted to industrialize the country, and it was opened up to foreign markets. He invested in infrastructure, education, medicine, and urban construction. Literacy was increased, oil was discovered, and the economy expanded.

He also drew criticism for repression of his own people, in particular for ordering the Hama massacre of 1982, which has been described as "the single deadliest act by any Arab government against its own people in the modern Middle East". Human Rights groups have detailed thousands of extrajudicial executions he committed against opponents of his regime. He was succeeded by his son, the even more brutal dictator Bashar al-Assad, in 2000.

Hafez ibn 'Ali ibn Sulayman

al-Assad was born into a poor family, in the town

of Qardaha in

the Latakia province

of western Syria (then

a French Mandate)

into a minority Alawite family.

He was the first member of the Assad family to

attend high school, Jules Jammal High

School in Lattakia. He joined the Ba'ath Party in

1946 at the age of 16.

Assad attended Homs Military Academy in

1952. In 1955, Assad graduated and was

commissioned as a lieutenant in

the Syrian Air Force, making him one

of the first Alawis to join the air force. He

became a combat and acrobatics display pilot,

flying the Gloster Meteor jet

fighter as well as other types. He shot down a

British plane during the Suez Operation. While at

the Academy, he met Mustafa Tlass.

In 1957, he was sent for additional training in

the Soviet Union. While stationed in Cairo, he developed a pan-Arab ideology

and came to believe that the U.A.R. concentrated

too much power in the hands of Gamal Abdel Nasser. Assad was then

assigned to a post in rural Egypt away from

political activity. At the breakup of the union in

1961, Assad was briefly imprisoned by the Egyptian authorities.

From 1961 to 1963 he worked at the Ministry of Sea Transportation while focusing on Ba'ath Party political activities. Assad and others planned the 1963 coup d'état, which took the Ba'ath Party to power. Following the coup, Assad returned to the Air Force in the rank of major. Syria was officially ruled by Amin Hafiz, a Sunni Muslim, but was in practice dominated by young Alawite Ba'athists.

The following year, 1964, Assad jumped several ranks to become a general and was appointed to the Ba'ath Party's regional command. The following year, he became Commander - in - Chief of the Air Force. This military power allowed Assad, operating in conjunction with Salah Jadid, to overthrow the government of Amin Hafiz in 1966.

In 1966, the Ba'ath launched a coup d'état within

the government and cleared the other parties from the

government. Assad became Minister of Defence and

wielded considerable influence over government policy.

However, there was tension between the dominant

radical wing of the Ba'ath Party, which promoted an

aggressive foreign policy and rapid social reform, and

Assad's more pragmatic, military based faction. After

being discredited by the failure of the Syrian

military in the Six - Day War in 1967,

and enraged by the aborted Syrian intervention in the

Jordanian - Palestinian Black September war, the

government faced conflict within its ranks. By the

time President Nureddin al-Atassi and the

de facto leader, deputy secretary general of the

Ba'ath Party Salah Jadid, realized the threat and

ordered Assad and Tlass be stripped of all party and

government power, it was too late. Assad swiftly

launched a bloodless intra - party coup, the Corrective Revolution of 1970.

The party was purged, Atassi and Jadid jailed, and

Assad loyalists installed in key posts throughout the

government.

Al-Assad inherited a dictatorial government shaped by years of unstable military rule that was organized along one-party lines after the Ba'athist coup. He increased repression, operating a vast web of police informers and agents. He became the object of a state sponsored cult of personality, which depicted him as a wise, just, and strong leader of Syria and of the Arab world in general.

The government of al-Assad initially achieved some popularity for bringing stability to the country, which had experienced dozens of attempted coups since 1948. He also implemented many social reforms and infrastructure projects, such as the Thawra (Revolution) dam on the Euphrates River. It was built with Soviet assistance, and still supplies much of Syria's electricity. Public schooling and other reforms were extended to larger segments of the population, and a rise in living standards occurred. The government's secularism meant that many members of religious minorities, such as the Alawites, Druze, and Christians, supported Assad, fearing a return to historic persecution under a Sunni Islamist successor government to Assad.

Assad continued previous Ba'ath policies by

overseeing massive increases in Syria's military

strength (again with Soviet support) and by

maintaining a strong Arab nationalist position.

School curricula and the state controlled media gave

much attention to the glorious past of Syria and the

Arabs, and portrayed al-Assad's government as the lone

uncorrupted champion of the Arab nation against Western imperialism and aggression. This propaganda aimed to

legitimize the government, but also to unify the

diverse and fractured Syrian society, and instill a

sense of national pride among the populace.

In 1979, a chain of assassinations took place in the artillery school in Aleppo. After almost a year, a member from the group believed to be behind the assassinations was injured and taken into custody by the Syrian intelligence system. He was identified as a member of the Muslim Brotherhood party. The party's goals were to eliminate all persons who had strong ties with the government or Ba'ath party, focusing on Ba'athists who were educated and had a good reputation within the government, or army high ranking members who were members of Assad's family or Alawites. It took Syrian intelligence a long time to penetrate the Muslim Brotherhood and diminish its power. In February 1982, Assad ordered the Syrian army to bombard the town of Hama in order to quell a revolt by the Muslim Brotherhood. In what became known as the Hama massacre, an estimated 17,000 to 40,000 people were killed, including about 1,000 soldiers.

In 1983, Assad suffered a heart attack and was

confined to hospital. He named a six man governing

council to run the country in his absence, among them

long time Defense Minister Mustafa Tlass; Hafez

al-Assad believed that they were less likely to try to

seize power. Despite this, rumors spread that Assad

was dead or nearly so, and indeed his condition was

serious. In 1984, his brother Rifaat al-Assad attempted

to use the security forces under his control to seize

power. His Defence Company troops of

some 50,000 men, complete with tanks and helicopters,

began putting up roadblocks throughout Damascus, and tensions between Hafez

loyalists and Rifaat supporters came close to all-out

war. The stand-off was not ended until Hafez, still

ill, rose from his bed to reassume power and speak to

the nation. He transferred command of the Defence

Company and,

without formal accusations, shortly after Rifaat was

exiled to France.

Even though Iraq was ruled by

another branch of the Ba'ath Party, Assad's

relations with Saddam Hussein were

extremely strained. Hostile rhetoric was intense,

and until Saddam's fall in 2003, Iraq was listed

in Syrian passports as one of the two countries no

Syrian citizen could visit (the other being

Israel). But with the exception of a few border

guard skirmishes and mutual support for cross -

border raids by opposition groups, no heavy

fighting broke out until 1991, when Syria joined

the US - led UN coalition to expel Iraq's military

forces from Kuwait during

the Persian Gulf War.

In that war, Assad contributed Syrian ground

troops to the battlefront.

To a large extent, Al-Assad's

foreign policy was shaped by Syria's attitude

toward Israel. During his presidency,

Syria played a major role in the 1973 Arab -

Israeli war. The war is presented by the

Syrian government as a victory, as Syria regained

some territory that had been occupied in 1967

through peace negotiations headed by Henry Kissinger. The Syrian

government refused to recognize the State of

Israel and referred to it as the "Zionist Entity."

Only in the mid 1990s did Hafez moderate his

country's policy towards Israel, as he realized

the loss of Soviet support meant a different

balance of power in the Middle East. Pressed by the United States, he engaged in

negotiations on the Israeli - annexed Golan

Heights, but these talks failed. Al-Assad believed

that what constituted Israel, the West Bank, and

Gaza, were an integral part of "Southern Syria."

Syria deployed troops to Lebanon in

1976, officially in response to a request from the

Lebanese government (by conspiracy) for Syrian

military intervention during the Lebanese Civil War. It is alleged

that the Syrian presence in Lebanon began earlier

with its involvement in as-Saiqa,

a Palestinian militia composed primarily of

Syrians. The Arab League agreed

to send a peacekeeping force mostly formed by

Syrian troops. The initial goals were to save the

Lebanese government from being overrun by the Left

and the Palestinian militancy. Critics allege that

this turned into an occupation by 1982, which is

not disputed within the Lebanese community. The

Syrian presence ended in 2005, due to UN

resolution 1559, after the Rafiq Hariri assassination

and the March 14 protests.

The hostile attitude to Israel meant vocal support for the Palestinians, but that did not translate into friendly relations with their organizations. Hafez al-Assad was always wary of independent Palestinian organizations, as he aimed to bring the Palestinian issue under Syrian control in order to use it as a political tool. He soon developed an implacable animosity towards Yassir Arafat's PLO, against which Syria fought bloody battles in Lebanon. As Arafat moved the PLO in a more moderate direction, seeking compromise with Israel, al-Assad feared regional isolation, and he resented the PLO underground's operations in Palestinian refugee camps in Syria. Arafat was depicted by Syria as a rogue madman and an American marionette, and after accusing him of supporting the Hama revolt, al-Assad backed the 1983 Abu Musa rebellion inside Arafat's Fatah movement. A number of unsuccessful Syrian attempts to kill Arafat were also made.

The attitude of Hafez al-Assad

towards Turkey was

quite hostile while he was in power. During his

rule, Syria – Turkey relations underwent

some serious political crises. He did not

recognize the annexation of Hatay by

Turkey, and all official maps continued to show

the territory as part of Syria. Furthermore, Syria

has supported the Kurdish separatist

organization PKK, which aimed an armed struggle

against Turkey for the creation of an independent Kurdistan, and allowed the PKK to

recruit Syrian Kurds to

fight against Turkey. He was blamed by Turkey for

sheltering the PKK leader Abdullah Öcalan. However,

this changed after Syria decided to force him out

of the country in 1998 when Turkey threatened to

invade Syria. After 1998, Syria started to crack

down on remaining PKK networks and forged better

ties with Turkey.

Assad had originally groomed

his son, Basil al-Assad as

his successor, but Basil died in a car accident in

1994. Assad then put a second son, Bashar, in intensive military and

political training, with Bashar becoming a staff

colonel in the military of Syria. Despite

some concerns of unrest within the government, the

succession ultimately went smoothly, and Bashar

holds office today. However, his rule has proven

even more brutal than that of his father. Several

thousands of Syrians have died during his efforts

to quell a popular revolution aimed at ousting his

regime. Hafez al-Assad died on June 10, 2000 of pulmonary fibrosis, though some

suggest that he died of blood cancer. He was 69.

Hafez al-Assad is buried together with Basil in a mausoleum in

his hometown of Qardaha.