<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Philip Edwrad Bertrand Jourdain, 1879

- Composer Jan Dismas Zelenka, 1679

- Diplomat and Cardinal Gasparo Contarini, 1483

PAGE SPONSOR

Jan Dismas Zelenka (16 October 1679, Louňovice pod Blaníkem, Czechia - 23 December 1745, Dresden, Germany), baptised Jan Lukáš Zelenka and previously also known as Johann Dismas Zelenka, was the most important Czech Baroque composer, whose music was notably daring with outstanding harmonic invention and mastery of counterpoint.

Zelenka was born in Louňovice pod Blaníkem, a small market town southeast of Prague, in Bohemia, as the eldest of the eight children born of Marie Magdalena (née Hájek) and Jiří Zelenka. The name Jan Dismas probably originates from his confirmation. His father was a schoolmaster and organist there; nothing more is known with certainty about Zelenka's early years. He received musical training at the Jesuit college Clementinum in Prague. Zelenka played the violone, the largest and lowest member of the viol family, analogous to the double bass in the violin family of stringed instruments. During his studies in Prague, Zelenka wrote his first compositions, all of them of oratorial character.

It is known that Zelenka had served Baron Hartig, the imperial governor who resided in Prague, before becoming a violone player in the royal orchestra at Dresden in about 1710. His emigration from Bohemia was most likely sudden, the reasons for it are not known and became the subject of some speculations. In some monographs, various personal reasons are alleged to be behind his escape, but the truth remains draped in mystery. His first opus in Dresden was "Missa Sanctae Caeciliae" (c.1711).

Zelenka continued his education in Vienna with the Habsburg Imperial Kapellmeister Johann Joseph Fux beginning in 1715. According to his own account, he spent 18 months in Vienna and was back in Dresden by 1719. Whether or not he ever went to Venice is unclear, but a Saxon court document of 1715 records a royal cash advance for such a journey by Zelenka along with Christian Petzold and Johann Georg Pisendel.

Except for a visit in 1723 to Prague, where Zelenka conducted his opus Dresden. Zelenka also composed a number of instrumental compositions in Prague, which was confirmed by the autograph of the score of Concerto à 8 concertanti, where was written: "six concerti written in a hurry in Prague in 1723".

In Dresden, Zelenka initially assisted the Kapellmeister, Johann David Heinichen, and gradually assumed Heinichen's duties as the latter's health declined. After Heinichen died in 1729, Zelenka applied for the post of Kapellmeister, but the post was given instead (in 1733) to Johann Adolf Hasse, reflecting the court's fashionable interest in opera as opposed to liturgical music. Alternatively, in 1735, Zelenka was given the title of "church composer" - "Compositeur of the Royal Court Capelle" (Johann Sebastian Bach had applied for this title in 1733, and was to receive it as well in 1736.) Zelenka was disappointed by the decision of the court, but, despite this, he was working very hard. It can be assumed, that this failure might paradoxically have opened the door for the composer´s free, independent creative effort of unprescribed work, and contributed thus indirectly on the extensive work of unique qualities.

Johann Sebastian Bach held Zelenka in high esteem, as evidenced by a letter from Bach's son C.P.E. Bach to Johann Nikolaus Forkel, of 13 January 1775, and Zelenka was a guest at Bach's home in Leipzig. Bach was allowed to copy some of his works, e.g., instructed his son, Wilhelm Friedemann, to copy the Amen from Zelenka's third Magnificat (ZWV 108) for use in Leipzig at St. Thomas' church.

In addition to compositional work, Zelenka was pedagogically active throughout his life and educated a number of prominent musicians of that time, e.g. Johann Joachim Quantz, J.G. Barter and J.G. Rollig. To his closest friends belonged (apart from Pisendel) also Georg Philipp Telemann and Sylvius Leopold Weiss.

Zelenka died of dropsy, that seems to have been the result of cardiac failure, in Dresden on December 23, 1745 and was buried on Christmas Eve. In his final years he wrote works that were never performed during his lifetime and generally felt isolated, broody and increasingly melancholic. He never married and had no children; his compositions and musical estate were purchased from his beneficiaries by the Electress of Saxony, Maria Josepha of Austria, and after his death were closely guarded (in contrast to his treatment when he was alive) and regarded as the court's possessions. Telemann, together with Pisendel tried unsuccessfully to publish Zelenka's "Responsoria". He wrote on the 17th of April 1756, with undisguised anger, that "the complete manuscript will be at the Dresden court, kept under lock and key as something rare…".

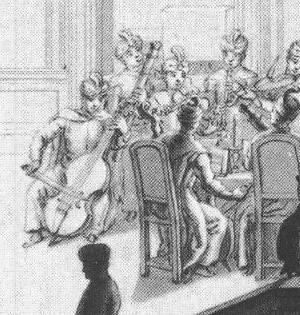

There

is no confirmed portrait of Zelenka, only one assumed composite sketch

and one drawing by Carl Heinrich Jakob Fehling dating from 1719,

portraying Zelenka as a violon player with an ensemble in Arabic

costumes, playing at what appears to be a festive dinner for the king's

court. It is necessary to mention a mirror - image black - and - white copy of the well known portrait of Fux, which has been passed off as a picture of Zelenka on several respected websites.

Zelenka's pieces are characterized by very daring compositional structure, with a highly spirited harmonic invention and perfection of the art of counterpoint. His works are often virtuosic and difficult to perform, but always fresh and surprising, with sudden turns of harmony, being always a challenge for their interpreters. In particular, his writing for bass instruments is far more demanding than that of other composers of his era, notably the "utopian" (as Heinz Holliger describes them) demands of the oboe scores in his trio sonatas. His instrumental works (the trio sonatas, capricci, and concertos) are exemplary models of his early style (1710s - 1720s). The six trio sonatas demand high virtuosity and expressive sensitivity from performers. As Zelenka was himself a violone player, he was known to write fast moving continuo parts with driving and complicated rhythm.

Zelenka was aware of the music in different regions of Europe. He wrote complex fugues, ornate operatic arias, galant - style dances, baroque recitatives, Palestrina like chorales, and virtuosic concertos. Zelenka's musical language is closest to Bach's, especially in its richness of contrapuntal harmonies and ingenious usage of fugal themes. Nevertheless, Zelenka's language is idiosyncratic in its unexpected harmonic twists, obsession with chromatic harmonies, huge usage of syncopation and tuplet figures, and unusually long phrases full of varied musical ideas. He is sometimes considered as Bach's Catholic counterpart, in his works.

Zelenka's music is influenced by Czech folk music. This way, he continues in the tradition of the progress of specific Czech national music, initiated by Adam Michna z Otradovic and brought to its culmination later, in works of Bedřich Smetana, Antonín Dvořák and Leoš Janáček.

The rediscovery of Jan Dismas Zelenka´s work is accredited to Bedřich Smetana, who rewrote some scores from the archives in Dresden and introduced one of the composer's orchestral suites in Prague's New Town Theatre festivals in 1863.

It was mistakenly assumed that many of Zelenka's autograph scores were destroyed during the fire bombing of Dresden in February 1945. However, the scores were not in the Katholische Hofkirche but were in a library north of the river. Some are certainly missing, but this probably happened gradually - and these represent only a small proportion of his extant works.

The interest in Zelenka's music has begun to grow, especially since the end of the 1950s. By the late 1960s and early 1970s all of Zelenka's instrumental compositions and selected liturgical music were published in Czechoslovakia. The most important revival was demonstrated by the first presentation of selected compositions by Czech conductor Milan Munclinger and his ensemble Ars Rediviva. They were three trio sonatas in 1958 - 1960, Sinfonia concertante in 1963 and the exquisite interpretation of "Lamentationes Jeremiae prophetae" with soloists Karl Berman, Nedda Casei and Theo Altmeyer in 1969. The music of Zelenka has become widely known and available since that time, through recordings and sparked the interest of musicians such as, Milan Munclinger, Heinz Holliger and Reinhard Goebel.

More than half of Zelenka's works have now been recorded, mostly in the Czech Republic and Germany. Many of his opuses are now being premiered for the first time in history by Czech choirs and orchestras and subsequently recorded from the 1990s. Those first recordings include, e.g., Missa Purificationis, Missa Sanctissimae trinitatis, Missa votiva, Missa Sancti Josephi, Il serpente di bronzo, and his secular works "Sub olea pacis" and "Il Diamante", performed by new Czech ensembles, using original instruments and interpretational techniques of the Baroque era, above all Musica Florea, Collegium 1704, Ensemble Inégal, Capella Regia Musicalis et al. It seems to be apparent, that Zelenka's opuses have not been completely explored yet and continuously bring new discoveries.

In honor of Jan Dismas Zelenka, "The autumn music festival" ("Podblanický hudební podzim" in Czech) was founded in 1984. Annual concerts of the composer's music are performed in many places in the region of his hometown.

The total number of Zelenka's known and attributed opuses is 249. His sacred vocal - instrumental music is in the center of the compositions - over 20 masses, 4 extensive oratoria and requiems, 2 Magnificat and Te Deum settings, 13 litanies, many psalms, hymns, antiphons and other similar works compromise his legacy. Zelenka also created a number of instrumental works - 6 trio or quartet sonatas, 5 capricci, 1 Hipocondrie, Concerto, Overture and Symphonie. The opuses nuumbering is marked „ZWV“ – „Zelenka - Werke - Verzeichnis“ (Zelenka Works Index)

The most appreciated Zelenka's sacred works are represented by masses, above all by Missa Purificationis (this is the last mass to include brass instruments) and his final 5 pieces, ZWV 17 - 21, called "High Mass" compositions, written from 1736 until 1741, during Zelenka's alleged compositional peak. The last three were also called "Missae ultimae" (Last Masses).