<Back to Index>

- Physicist Abram Fyodorovich Ioffe, 1880

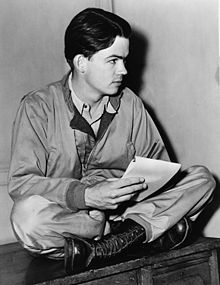

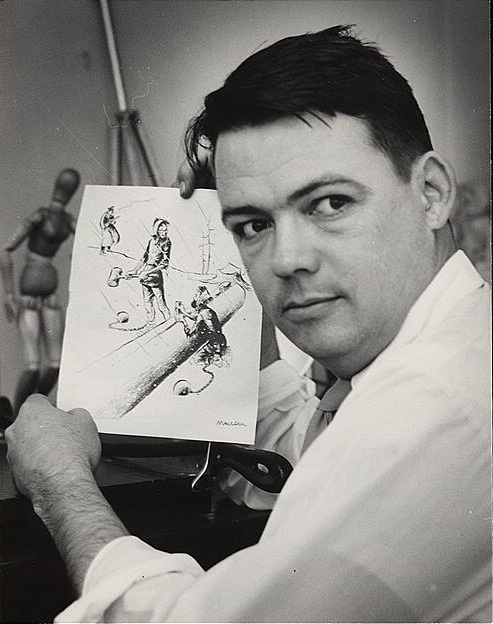

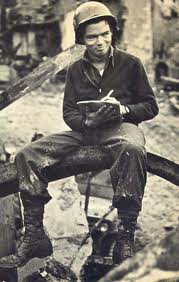

- Cartoonist William Henry "Bill" Mauldin, 1921

- Admiral of the Royal Navy John Byng, 1704

PAGE SPONSOR

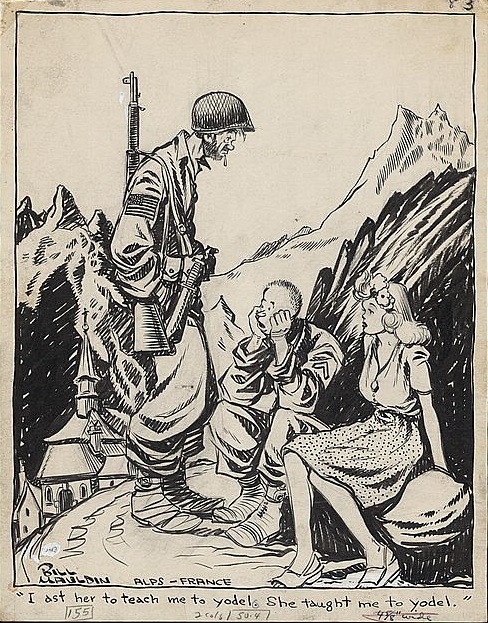

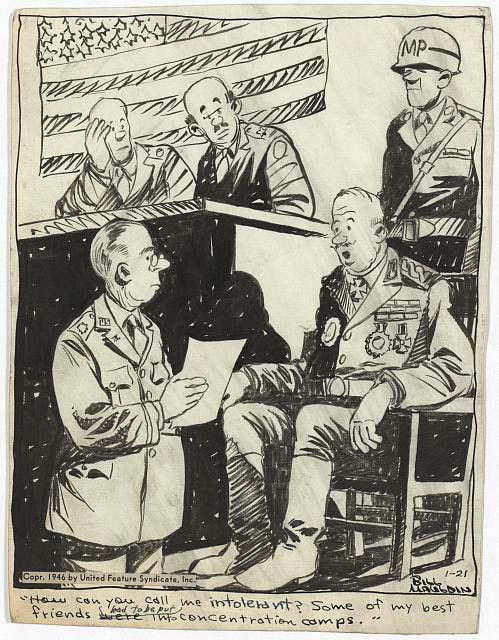

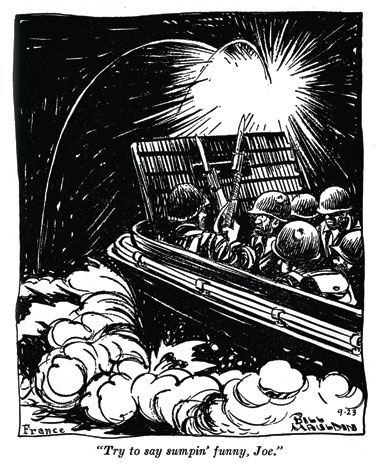

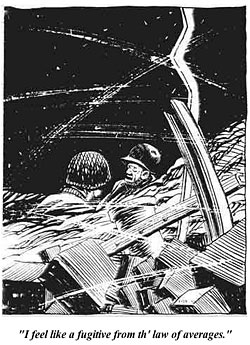

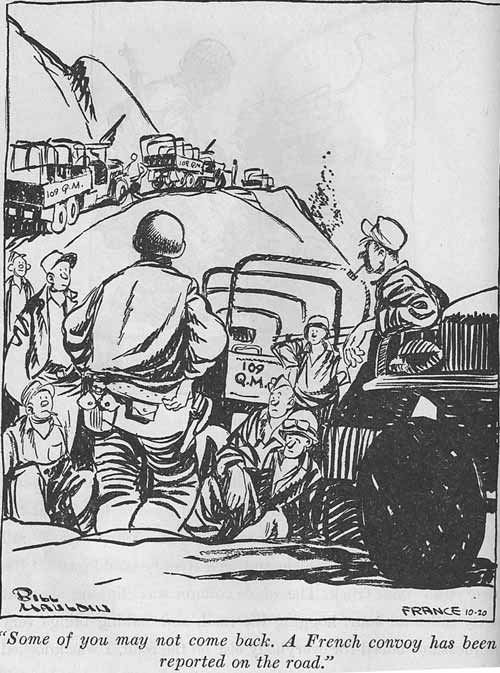

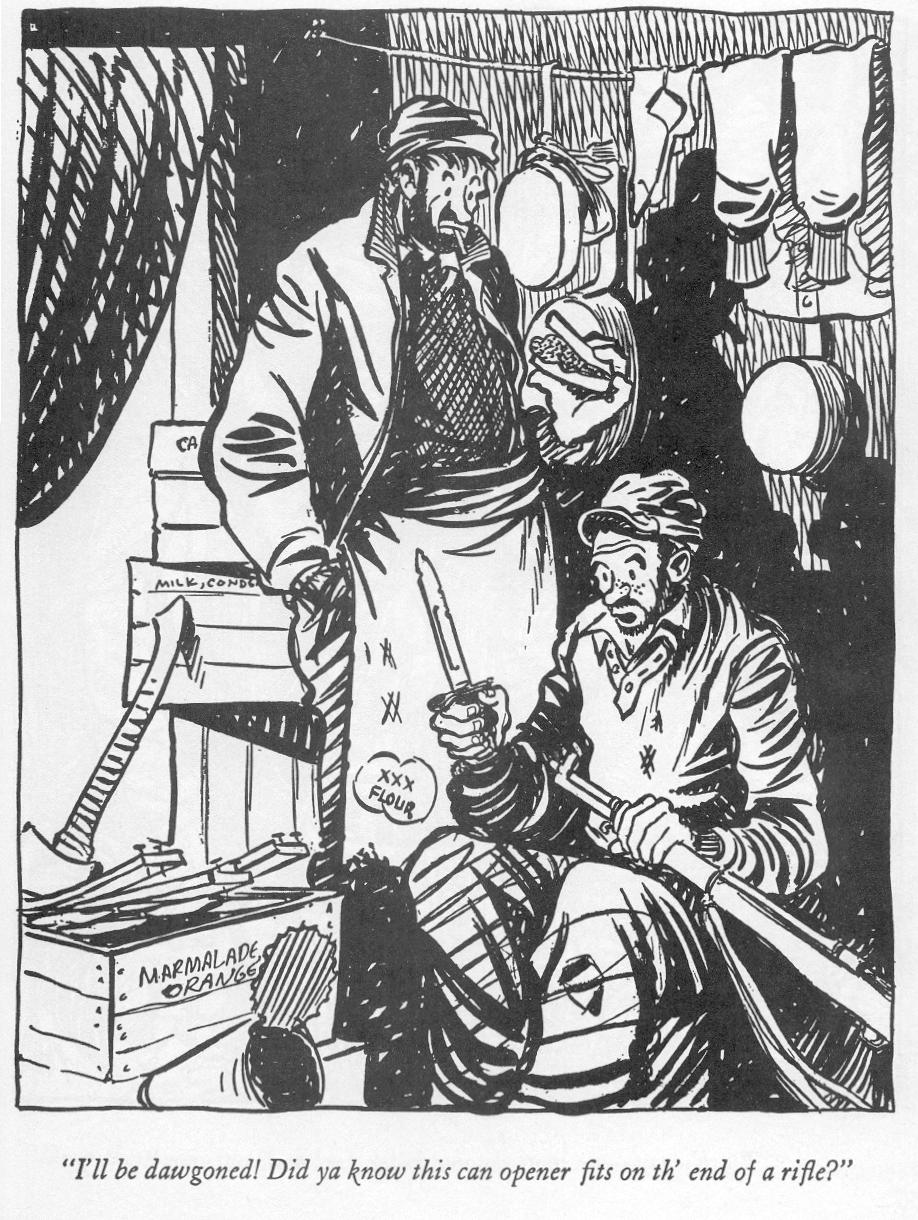

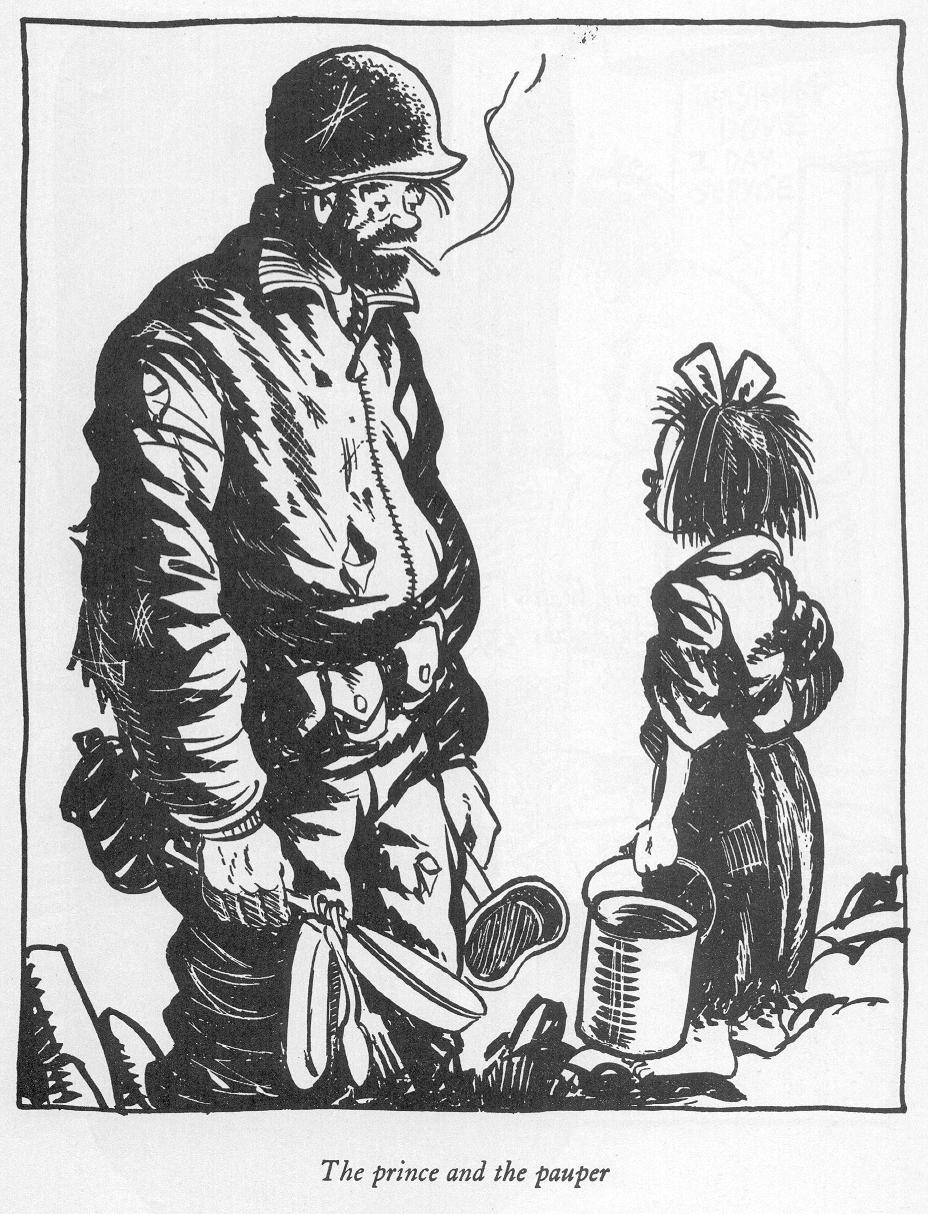

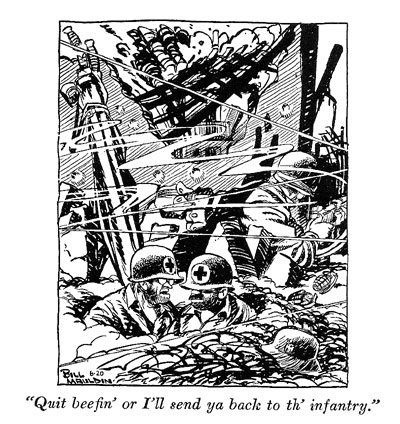

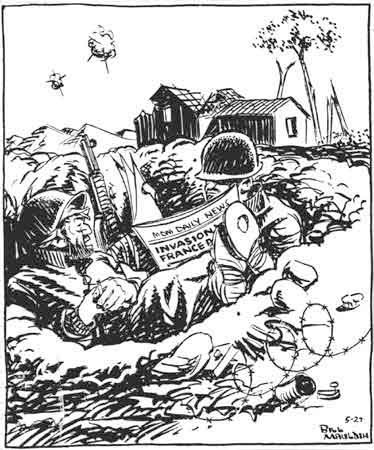

William Henry "Bill" Mauldin (October 29, 1921 – January 22, 2003) was a two - time Pulitzer Prize winning editorial cartoonist from the United States. He was most famous for his World War II cartoons depicting American soldiers, as represented by the archetypal characters "Willie and Joe", two weary and bedraggled infantry troopers who stoically endure the difficulties and dangers of duty in the field. These cartoons were broadly published and distributed in the American army abroad and in the United States.

Mauldin was born in Mountain Park, New Mexico. His grandfather had been a civilian cavalry scout in the Apache Wars and his father was an artilleryman in World War I. After growing up there and in Phoenix, Arizona, Mauldin took courses at the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts under the tutoring of Ruth VanSickle Ford. While in Chicago, Mauldin met Will Lang Jr. and became fast friends with him. Mauldin entered the US Army via the Arizona National Guard in 1940.

While in the 45th Infantry Division, Mauldin volunteered to work for the unit's newspaper, drawing cartoons about regular soldiers or "dogfaces". Eventually he created two cartoon infantrymen, Willie (who was modeled after his comrade and friend Irving Richtel) and Joe, who became synonymous with the average American GI.

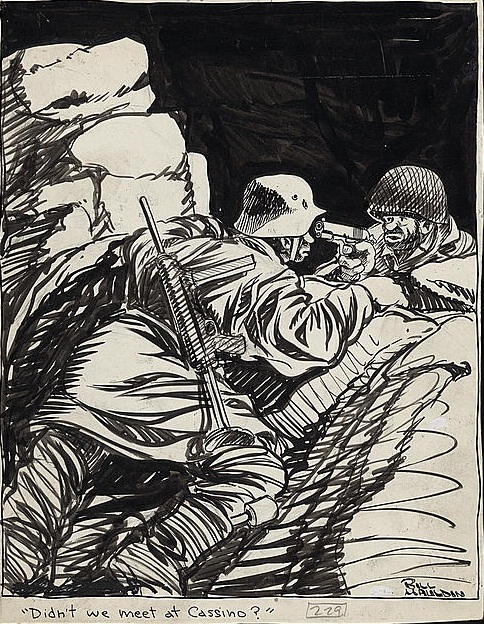

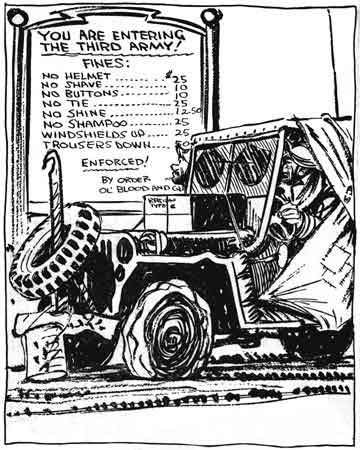

During July 1943, Mauldin's cartoon work continued when, as a sergeant of the 45th Division's press corps, he landed with the division in the invasion of Sicily and later in the Italian campaign. Mauldin began working for Stars and Stripes, the American soldiers' newspaper; as well as the 45th Division News, until he was officially transferred to the Stars and Stripes in February 1944. By March 1944, he was given his own jeep, in which he roamed the front, collecting material and producing six cartoons a week. His cartoons were viewed by soldiers throughout Europe during World War II, and were also published in the United States. The War Office supported their syndication, not only because they helped publicize the ground forces but also to show the grim and bitter side of war, which helped show that victory would not be easy. Willie was on the cover of Time Magazine in 1945, and Mauldin himself made the cover in 1958.

Those officers who had served in the army before the war were generally offended by Mauldin, who parodied the spit - shine and obedience - to - order - without - question view that was more easily maintained during that time of peace. General George Patton once summoned Mauldin to his office and threatened to "throw his ass in jail" for "spreading dissent," this after one of Mauldin's cartoons made fun of Patton's demand that all soldiers must be clean - shaven at all times, even in combat. But Dwight Eisenhower, Supreme Commander European Theater, told Patton to leave Mauldin alone, because he felt that Mauldin's cartoons gave the soldiers an outlet for their frustrations. Mauldin told an interviewer later, "I always admired Patton. Oh, sure, the stupid bastard was crazy. He was insane. He thought he was living in the Dark Ages. Soldiers were peasants to him. I didn't like that attitude, but I certainly respected his theories and the techniques he used to get his men out of their foxholes."

Mauldin's

cartoons made him a hero to the common soldier. GIs often credited him

with helping them to get through the rigors of the war. His credibility

with the common soldier increased in September 1943, when he was wounded

in the shoulder by a German mortar while visiting a machine gun crew

near Monte Cassino. By the end of the war he also received the Army's Legion of Merit for his cartoons. (Mauldin wanted to have Willie and Joe be killed on the last day of combat, but Stars and Stripes dissuaded him.)

In 1945, at the age of 23, Mauldin won the Pulitzer Prize. The first collection of his work, Up Front, was a best seller. The cartoons are interwoven with an impassioned telling of his observations of war.

After World War II, Mauldin turned to drawing political cartoons expressing a generally civil libertarian view associated with groups such as the American Civil Liberties Union. These were not well received by newspaper editors, who were hoping for more apolitical Willie and Joe cartoons. But Mauldin's attempt to carry Willie and Joe into civilian life was also unsuccessful, as documented in his memoirs, Back Home, in 1947.

He abandoned cartooning for a while, working as a film actor, freelance writer, and illustrator of articles and books, including one on the Korean War. He drew Willie and Joe only a few times afterwards: for the funerals of Omar Bradley and George C. Marshall, both of them considered "soldiers' generals"; for a Life Magazine article on the "New Army"; and to memorialize fellow cartoonist Milton Caniff.

In 1956, he ran unsuccessfully for the United States Congress as a Democrat in

New York's 28th Congressional District. Mauldin had this to say about

his run for Congress: "I jumped in with both feet and campaigned for

seven or eight months. I found myself stumping around up in these rural

districts and my own background did hurt there. A farmer knows a farmer

when he sees one. So when I was talking about their problems I was a

very sincere candidate, but when they would ask me questions that had to

do with foreign policy or national policy, obviously I was pretty far

to the left of the mainstream up there. Again, I'm an old Truman Democrat, I'm not that far left, but by their lives I was pretty far left."

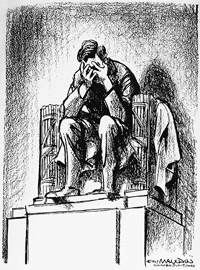

In 1958, he returned to cartooning on the editorial pages of the St. Louis Post - Dispatch. The following year, he won a second Pulitzer Prize and the National Cartoonist Society Award for Editorial Cartooning. In 1961 he received their Reuben Award as well. In 1962 he moved to the Chicago Sun - Times. One of his most famous post - war cartoons appeared in Chicago in 1963, following the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. The cartoon shows the statue of Abraham Lincoln at the Lincoln Memorial, his head in his hands, crying.

In 1969, Mauldin was commissioned by the National Safety Council to illustrate the booklet on traffic safety, which the council published every year. These pamphlets were regularly issued without copyright, but for this issue it was pointed out that Mauldin's cartoons were under copyright even though the rest of the pamphlet was not.

Mauldin remained with the Sun - Times until his retirement in 1991. He was inducted into the St. Louis Walk of Fame on May 19, 1991. On September 19, 2001, Sergeant Major of the Army Jack L. Tilley presented Mauldin with a personal letter from Army Chief of Staff General Eric K. Shinseki, a hardbound book with notes from other senior Army leaders and several celebrities to include Walter Cronkite, Tom Brokaw and Tom Hanks. He also promoted Mauldin to the honorary rank of first sergeant.

In 1998, Mauldin drew "Willie and Joe" for publication one last time, as part of a Veterans Day strip for the popular comic, Peanuts. The creator of Peanuts and a World War II veteran himself, Charles M. Schulz, had long described Mauldin as his hero. He signed the strip Schulz, and my Hero, and then had Mauldin sign his name underneath. Mauldin died on January 22, 2003, from complications of Alzheimer's disease and a bathtub scalding. He was buried in Arlington National Cemetery on January 29, 2003. Married three times, he was survived by 7 children. (His daughter Kaja had died of Non - Hodgkins Lymphoma in 2001.)

On March 31, 2010, the United States Post Office released a first - class denomination ($.44) postage stamp in Mauldin's honor depicting him with Willie & Joe.

In 2005, Mauldin was inducted into the Oklahoma Cartoonists Hall of Fame in Pauls Valley, Oklahoma by Michael Vance. The Oklahoma Cartoonists Collection, created by Vance, is located in the Toy and Action Figure Museum.

From 1969 to 1998, cartoonist Charles M. Schulz (himself a veteran of World War II) regularly paid tribute to Bill Mauldin in his Peanuts comic strip on Veterans Day. In the strips, Snoopy, dressed as an army vet, would annually go to Mauldin's house to "quaff a few root beers and tell war stories." By the end of the strip Schulz had depicted 17 of Snoopy's visits. Schulz also paid tribute to Rosie the Riveter in 1976, and Ernie Pyle in 1997 & 1999.

The films Up Front (1951) and Back at the Front (1952) were based on Mauldin's Willie and Joe characters; however, when Mauldin's suggestions were ignored in favor of making a slapstick comedy, he returned his advising fee; he said he had never seen the result.

Mauldin also appeared as an actor in the 1951 films The Red Badge of Courage and Teresa, and as himself in the 1998 documentary America in the '40s. He also appeared in on-screen interviews in the Thames documentary The World at War.