<Back to Index>

- Economist William Stanley Jevons, 1835

- Poet Innokentiy Fyodorovich Annensky, 1855

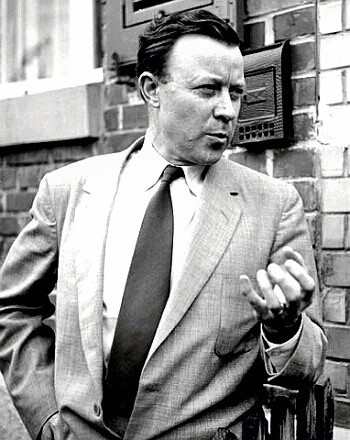

- Labor Union Leader Walter Philip Reuther, 1907

PAGE SPONSOR

Walter Philip Reuther (September 1, 1907 – May 9, 1970) was an American labor union leader, who made the United Automobile Workers a major force not only in the auto industry but also in the Democratic Party in the mid 20th century. He was a socialist in the early 1930s becoming a leading liberal and supporter of the New Deal coalition.

Reuther was born in Wheeling, West Virginia, the son of a socialist brewery worker who had immigrated from Germany. Throughout his career he was close to his brothers and co-workers Victor Reuther and Roy Reuther. Reuther joined the Ford Motor Company in 1927 as an expert tool and die maker but was laid off in 1932 as the Great Depression worsened. His Ford employment record states that he quit voluntarily, but Reuther himself always maintained that he was fired for his increasingly visible socialist activities. He and his brothers went to Europe and then worked 1933 - 35 in an auto plant at Gorky in the Soviet Union. While a committed socialist, he never became a Communist. At the end of the trip he wrote, "the atmosphere of freedom and security, shop meetings with their proletarian industrial democracy; all these things make an inspiring contrast to what we know as Ford wage slaves in Detroit. What we have experienced here has reeducated us along new and more practical lines." Unhappy with the lack of political freedom in Russia, Reuther returned to the United States where he found employment at General Motors and became an active member of the United Automobile Workers (UAW).

Reuther was a Socialist Party member; he may have paid dues to the Communist Party for some months in 1935 - 36; he has been accused of attending a Communist Party planning meeting as late as February 1939. Reuther cooperated with the Communists in the later 1930s; this was the period of the Popular Front, and they agreed with him on internal issues of the UAW; but his associations were with anti - Stalinist Socialists.

Reuther remained active in the Socialist Party and in 1937 failed in his attempt to be elected to the Detroit Common Council.

However, impressed by the efforts by President Franklin D. Roosevelt to

tackle inequality, he eventually joined the Democratic Party. In

1936 he became president of tiny local 174 (with 100 members), which on

paper had responsibility for 100,000 auto workers on the west side of Detroit, Michigan.

Reuther led several strikes and in 1937 and 1940 was hospitalized after

being badly beaten by strike breakers. He also survived two

assassination attempts, and his right hand was permanently crippled in

an attack on April 20, 1948. He had a highly publicized confrontation with Ford security forces on May 26, 1937, also known as the Battle of the Overpass.

By this time, thanks to the sit-down strikes, UAW membership had

exploded and Local 174 was a power inside the UAW. As a senior union organizer, Reuther helped win major strikes for union recognition against General Motors in 1940 and Ford in 1941. After Pearl Harbor,

Reuther strongly supported the war effort and refused to tolerate

wildcat strikes that might disrupt munitions production. He worked for

the War Manpower Commission, the Office of Production Management, and

the War Production Board. He led a 113 day strike against General Motors

in 1945 - 1946; it only partially succeeded. He never received the power

he wanted to inspect company books or have a say in management, but he

achieved increasingly lucrative wage and benefits contracts. In 1946 he

narrowly defeated R.J. Thomas for the UAW presidency, and soon after he

purged the UAW of all Communist elements. He was active in the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) umbrella as well, taking the lead in expelling eleven communist - led unions from the CIO in 1949. As a prominent figure in the anti - Communist left, he was a founder of the Americans for Democratic Action in

1947. He became president of the CIO in 1952, and negotiated a merger

with George Meany and the American Federation of Labor immediately

after, which took effect in 1955. In 1949 he led the CIO delegation to

the London conference that set up the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions in opposition to the Communist dominated World Federation of Trade Unions.

He had left the Socialist party in 1939, and throughout the 1950s and

1960s was a leading spokesman for liberal interests in the CIO and in

the Democratic party. Reuther

delivered contracts for his membership through brilliant negotiating

tactics. He would pick one of the "Big three" automakers, and if it did

not offer concessions, he would strike it and let the other two absorb

its sales. Besides high hourly wage rates and paid vacations, Reuther

negotiated these benefits for his union: employer funded pensions

(beginning in 1950 at Chrysler), medical insurance (beginning at GM in

1950), and supplementary unemployment benefits (beginning at Ford in

1955). Reuther tried to negotiate lower automobile prices for the

consumer with each contract, with limited success.

Toward the end of his life, when he took the UAW out of the AFL - CIO for a short lived alliance with the Teamsters Union, and marched with the United Farm Workers in Delano, California,

Reuther seemed to be dissatisfied, looking for the ability to challenge

the injustices that had made the union movement so vital in the 1930s.

He strongly supported the Civil Rights movement; Reuther was an active

supporter of African American civil rights and participated in both the

March on Washington for Freedom and Jobs (August, 1963) and the Selma

to Montgomery March (March, 1965). He stood beside Martin Luther King Jr. while he made the "I Have A Dream" speech, during the 1963 March on Washington. Although critical of the Vietnam War,

he supported Lyndon Johnson and Hubert Humphrey in 1968, and met weekly

with President Johnson during 1964 - 1965. He was instrumental in

mobilizing UAW resources to minimize the threat that George Wallace would win more than 10 percent of union votes (Wallace won about 9 percent in the North). On May 9, 1970, Reuther, his wife May, architect Oscar Stonorov,

and also a bodyguard, the pilot and co-pilot were killed when their

chartered Lear - Jet crashed in flames at 9:33 P.M. Michigan time. The

plane, arriving from Detroit in rain and fog, was on final approach to

the Pellston, Michigan, airstrip near the union's recreational and educational facility at Black Lake, Michigan. In

October 1968, a year and a half before the fatal crash, Reuther and his

brother Victor were almost killed in a small private plane as it

approached Dulles airport. Both incidents are amazingly similar; the

altimeter in the fatal crash was believed to have malfunctioned. When

Victor Reuther was interviewed many years after the fatal crash he said

"I and other family members are convinced that both the fatal crash and

the near fatal one in 1968 were not accidental." The FBI still refuses

to turn over nearly 200 pages of documents pertaining to Walter

Reuther's death, and correspondence between field offices and J. Edgar

Hoover. Walter Reuther appears in Time magazine's list of the 100 most influential people of the 20th century. He was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom posthumously in 1995 by President Bill Clinton. In retrospect, audio tapes from the Johnson White House, revealed a quid pro quo unrelated

to chicken. In January 1964, President Johnson attempted to persuade

Reuther not to initiate a strike just prior to the 1964 election and to

support the president's civil rights platform. Reuther in turn wanted

Johnson to respond to Volkswagen's increased shipments to the United States. The Chicken Tax directly curtailed importation of German built Volkswagen Type 2 vans in configurations that qualified them as light trucks — that is, commercial vans and pickups. In

1964 U.S. imports of "automobile trucks" from West Germany declined to

a value of $5.7 million — about one - third the value imported in the

previous year. Soon after, Volkswagen cargo vans and pickup trucks, the

intended targets, "practically disappeared from the U.S. market." As of 2009, the Chicken tax remains in effect.