<Back to Index>

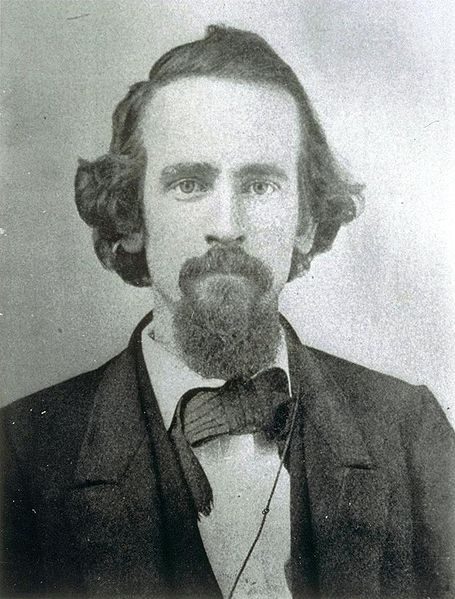

- Political Economist Henry George, 1839

- Writer and Anarchist Philosopher Hans Henrik Jæger, 1854

- President Pro Tempore of the U.S. Senate William Pierce Frye, 1830

PAGE SPONSOR

Henry George (September 2, 1839 – October 29, 1897) was an American writer, politician and political economist, who was the most influential proponent of the land value tax, also known as the "single tax" on land. He inspired the economic philosophy known as Georgism, whose main tenet is that people should own what they create, but that everything found in nature, most importantly land, belongs equally to all humanity. His most famous work, Progress and Poverty (1879), is a treatise on inequality, the cyclic nature of industrial economies, and the use of the land value tax as a possible remedy.

George was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to a lower middle class family, the second of ten children of Richard S.H. George and Catharine Pratt (Vallance) George. His formal education ended at age 14 and he went to sea as a foremast boy at age 15 in April 1855 on the Hindoo, bound for Melbourne and Calcutta. He returned to Philadelphia after 14 months at sea to become an apprentice typesetter before settling in California. After a failed attempt at gold mining he began work with the newspaper industry during 1865, starting as a printer, continuing as a journalist, and ending as an editor and proprietor. He worked for several papers, including four years (1871 – 1875) as editor of his own newspaper San Francisco Daily Evening Post.

In California, George became enamored of Annie Corsina Fox, an eighteen year old Australian girl who had been orphaned and was living with an uncle. The uncle, a prosperous, strong minded man, was opposed to his niece's impoverished suitor. But the couple, defying him, eloped and married during late 1861, with Henry dressed in a borrowed suit and Annie bringing only a packet of books. The marriage was a happy one and four children were born to them. Fox's mother was Irish Catholic, and while George remained an Evangelical Protestant, the children were raised Catholic. On November 3, 1862 Annie gave birth to future United States Representative from New York, Henry George, Jr. (1862 – 1916). Early on, even with the birth of future sculptor, Richard F. George (1865 – September 28, 1912), the family was near starvation, but George's increasing reputation and involvement in the newspaper industry lifted them from poverty.

George's

other two children were both daughters. The first was Jennie George,

(c. 1867 - 1897), later to become Jennie George Atkinson. George's other daughter was Anna Angela George, (b. 1879), who would become mother of both future dancer and choreographer, Agnes de Mille and future actress Peggy George, (who was born Margaret George de Mille). George began as a Lincoln Republican, but then became a Democrat, once losing an election to the California State Assembly. He was a strong critic of railroad and mining interests, corrupt politicians, land speculators, and labor contractors. One day during 1871 George went for a horseback ride and stopped to rest while overlooking San Francisco Bay. He later wrote of the revelation that he had: Furthermore, on a visit to New York City,

he was struck by the apparent paradox that the poor in that

long established city were much worse off than the poor in less

developed California. These observations supplied the theme and title

for his 1879 book Progress and Poverty,

which was a great success, selling over 3 million copies. In it George

made the argument that a sizeable portion of the wealth created by

social and technological advances in a free market economy is possessed by land owners and monopolists via economic rents, and that this concentration of unearned wealth is the main cause of poverty.

George considered it a great injustice that private profit was being

earned from restricting access to natural resources while productive

activity was burdened with heavy taxes, and indicated that such a system

was equivalent to slavery — a concept somewhat similar to wage slavery. George

was in a position to discover this pattern, having experienced poverty

himself, knowing many different societies from his travels, and living

in California at a time of rapid growth. In particular he had noticed

that the construction of railroads in California was increasing land values and rents as fast or faster than wages were rising.

During 1880, now a popular writer and speaker, George moved to New York City, becoming closely allied with the Irish nationalist community despite being of English ancestry. From there he made several speaking journeys abroad to places such as Ireland and Scotland where

access to land was (and still is) a major political issue. During 1886

George campaigned for mayor of New York City as the candidate of the

United Labor Party, the short lived political society of the Central Labor Union. He polled second, more than the Republican candidate Theodore Roosevelt. The election was won by Tammany Hall candidate Abram Stevens Hewitt by what many of George's supporters believed was fraud. In the 1887 New York state elections George came in a distant third in the election for Secretary of State of New York.

The United Labor Party was soon weakened by internal divisions: the

management was essentially Georgist, but as a party of organised labor

it also included some Marxist members who did not want to distinguish between land and capital, many Catholic members who were discouraged by the excommunication of Father Edward McGlynn,

and many who disagreed with George's free trade policy. Against the

advice of his doctors, George campaigned for mayor again during 1897, this time as an Independent Democrat.

Henry George died of a stroke four days before the election. An estimated 100,000 people attended his funeral on Sunday, October 30, 1897 where the Reverend Lyman Abbott delivered an address, "Henry George: A Remembrance". Henry George is best known for his argument that the economic rent of land should be shared by society rather than being owned privately. The clearest statement of this view is found in Progress and Poverty: "We must make land common property." By

taxing land values, society could recapture the value of its common

inheritance, and eliminate the need for taxes on productive activity. Modern - day environmentalists have agreed with the idea of the earth as the common property of humanity – and some have endorsed the idea of ecological tax reform, including substantial taxes or fees on pollution as a replacement for "command and control" regulation.

George was opposed to tariffs, which were at the time both the major method of protectionist trade policy and an important source of federal revenue (the federal income tax having not yet been introduced). Later in his life, free trade became a major issue in federal politics and his book Protection or Free Trade was read into the Congressional Record by five Democratic congressmen.

George was one of the earliest, strongest and most prominent advocates for adoption of the Secret Ballot in the U.S.A. George supported government issued notes such as the greenback rather than gold or silver currency or money backed by bank credit. In the United Kingdom during 1909, the Liberal Government of the day attempted to implement his ideas as part of the People's Budget. This caused a crisis which resulted indirectly in reform of the House of Lords. George's ideas were also adopted to some degree in Australia, Singapore, South Africa, South Korea, and Taiwan. In these countries, governments still levy some type of land value tax, albeit with exemptions. In Denmark, the Danmarks Retsforbund (known

in English as the Justice Party or Single - Tax Party) was founded in

1919. The party's platform is based upon the land tax principles of

Henry George. The party was elected to parliament for the first time in

1926, and they were moderately successful in the post - war period and

managed to join a governing coalition with the Social Democrats and the

Social Liberal Party from the years 1957 - 60. In 1960 they dropped out of

the parliament. However in the 1973 Danish parliamentary election (the

so-called Landslide Election) the party won 5 seats in Folketinget,

because of their opposition against Danish membership of the European

Economic Community. They were represented until 1981 and also in the

European Parliament 1978 - 79 (by Ib Christensen). The 1970s were followed

by a dropoff of party support, and the party ceased to run at a

national level in 1990, but in 2005 the party ran together with

Minoritetspartiet (the Minority Party): this wasn't with any success

since the Minority Party only achieved 0.3% of the votes. Fairhope, Alabama was

founded as a colony by a group of his followers as an experiment to try

to test his concepts. Much of he land around Fairhope is owned by the Fairhope Single Tax Corporation, which leases the land for 99 years (transferable and renewable for another 99 years at transfer). Although both advocated worker's rights, Henry George and Karl Marx were antagonists. Marx saw the Single Tax platform as a step backwards from the transition to communism. On his part, Henry George predicted that if Marx's ideas were tried the likely result would be a dictatorship. Henry

George's popularity decreased gradually during the 20th century, and he

is little known today. However, there are still many Georgist organizations in existence. Many people who still remain famous were influenced by him. For example, George Bernard Shaw, Leo Tolstoy's To The Working People, Sun Yat Sen, Herbert Simon, and David Lloyd George. A follower of George, Lizzie Magie, created a board game called The Landlord's Game in 1904 to demonstrate his theories. After further development this game led to the modern board game Monopoly. J. Frank Colbert, a newspaperman, a member of the Louisiana House of Representatives and later the mayor of Minden, joined the Georgist movement during 1927. During 1932, Colbert addressed the Henry George Congress at Memphis, Tennessee. Also notable is Silvio Gesell's Freiwirtschaft,

in which Gesell combined Henry George's ideas about land ownership and

rents with his own theory about the money system and interest rates and

his successive development of Freigeld. In his last book, Where do we go from here: Chaos or Community?, Martin Luther King, Jr referenced Henry George in support of a guaranteed minimum income. George's influence has ranged widely across the political spectrum. Noted progressives such as consumer rights advocate (and U.S. Presidential candidate) Ralph Nader and Congressman Dennis Kucinich have spoken positively about George in campaign platforms and speeches. His ideas have also received praise from conservative journalists William F. Buckley, Jr. and Frank Chodorov, Fred E. Foldvary and Stephen Moore. The libertarian political and social commentator Albert Jay Nock was also an avowed admirer, and wrote extensively on the Georgist economic and social philosophy. Mason Gaffney, an American economist and a major Georgist critic of neoclassical economics,

argued that neoclassical economics was designed and promoted by

landowners and their hired economists to divert attention from George's

extremely popular philosophy that since land and resources are provided

by nature, and their value is given by society, they - rather than labor

or capital - should provide the tax base to fund government and its

expenditures. The Robert Schalkenbach Foundation,

an incorporated "operating foundation," also publishes copies of

George's work on economic reform and sponsors academic research into his

policy proposals. George developed what he saw as a crucial feature of his own theory of economics in a critique of an illustration used by Frédéric Bastiat in order to explain the nature of interest and profit.

Bastiat had asked his readers to consider James and William, both

carpenters. James has built himself a plane, and has lent it to William

for a year. Would James be satisfied with the return of an equally good

plane a year later? Surely not! He'd expect a board along with it, as

interest. The basic idea of a theory of interest is to understand why.

Bastiat said that James had given William over that year "the power,

inherent in the instrument, to increase the productivity of his labor,"

and wants compensation for that increased productivity. George did not accept this explanation. He wrote, "I am inclined to think that if all wealth consisted

of such things as planes, and all production was such as that of

carpenters -- that is to say, if wealth consisted but of the inert

matter of the universe, and production of working up this inert matter

into different shapes, that interest would be but the robbery of

industry, and could not long exist." But some wealth is inherently

fruitful, like a pair of breeding cattle, or a vat of grape juice soon

to ferment into wine. Planes and other sorts of inert matter (and the

most lent item of all —- money itself) earn interest indirectly, by being

part of the same "circle of exchange" with fruitful forms of wealth

such as those, so that tying up these forms of wealth over time incurs

an opportunity cost. George's theory had its share of critiques. Austrian school economist Eugen von Böhm - Bawerk, for example, expressed a negative judgment of George's discussion of the carpenter's plane. On page 339 of his treatise, Capital and Interest, he wrote: Later, George argued that the role of time in production is pervasive. In "The Science of Political Economy", he writes: The

importance ... of this principle that all production of wealth requires

time as well as labor we shall see later on; but the principle that

time is a necessary element in all production we must take into account

from the very first. According

to Oscar B. Johannsen, "Since the very basis of the Austrian concept of

value is subjective, it is apparent that George's understanding of

value paralleled theirs. However, he either did not understand or did

not appreciate the importance of marginal utility." Another spirited response came from British biologist T.H. Huxley in his article "Capital - the Mother of Labour," published in 1890 in the journal The Nineteenth Century.

Huxley used the principles of energy science to undermine George's

theory, arguing that, energetically speaking, labor is unproductive. George's early emphasis on the "productive forces of nature" is now dismissed even by otherwise Georgist authors.

“ I

asked a passing teamster, for want of something better to say, what

land was worth there. He pointed to some cows grazing so far off that

they looked like mice, and said, 'I don't know exactly, but there is a

man over there who will sell some land for a thousand dollars an acre.'

Like a flash it came over me that there was the reason of advancing

poverty with advancing wealth. With the growth of population, land

grows in value, and the men who work it must pay more for the privilege. ”

Some of George's earliest articles to gain him fame were on his opinion that Chinese immigration should be restricted. Although

he thought that there might be some situations in which immigration

restriction would no longer be necessary and admitted his first

analysis of the issue of immigration was "crude", he defended many of

these statements for the rest of his life. In

particular he argued that immigrants accepting lower wages had the

undesirable effect of forcing down wages generally. He acknowledged,

however, that wages could only be driven down as low as whatever

alternative for self - employment was available.