<Back to Index>

- Philosopher and Social Activist Jane Addams, 1860

- Writer Nicolae Filimon, 1819

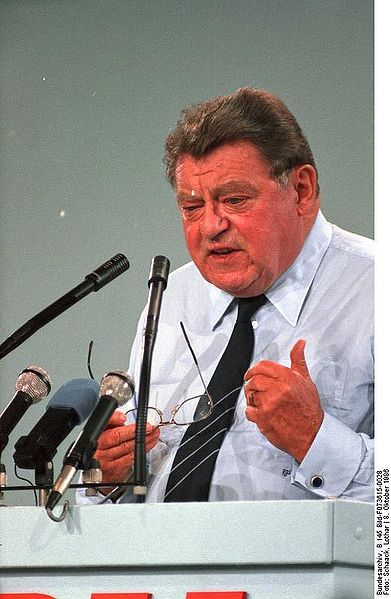

- Minister of Defence and Minister of Finance Franz Josef Strauß, 1915

PAGE SPONSOR

Franz Josef Strauss (German: Franz Josef Strauß; 6 September 1915 – 3 October 1988) was a German politician. He was the leader of the Christian Social Union, member of the federal cabinet in different positions and long time minister - president of the state of Bavaria.

During his political career Strauss was something of a divisive figure. As a younger man he served in several positions in the federal cabinet, and had some brushes with scandal during this time. After the 1969 federal elections, West Germany's conservative alliance found itself out of power for the first time since the founding of the Federal Republic. At this time, Strauss became more identified with the regional politics of Bavaria. While he ran for the chancellorship as the candidate of the CDU / CSU in 1980, for the rest of his life Strauss never again held federal office. From 1978 until his death in 1988, he was the head of the Bavarian government. His last two decades were also marked by a fierce rivalry with CDU leader Helmut Kohl.

Born in Munich, as the second child of a butcher, Strauss studied German letters, history and economics at the University of Munich from 1935 to 1939. In World War II, he served in the German Wehrmacht on the Western and Eastern Fronts. While on furlough, he passed the German state exams to become a teacher. After suffering from severe frostbite on the Eastern Front in early 1943, he served as an Offizier für wehrgeistige Führung (Nationalsozialistischer Führungsoffizier (NSFO), political officer) at the anti - aircraft artillery school in Altenstadt, near Schongau. He held the rank of Oberleutnant at the end of the war. In 1945 he served as translator for the US army and especially for Ernest F. Hauser, who was first lieutenant in CIC military intelligence. He called himself Franz Strauss until soon after the war when he started using his middle name as well. Strauss married Marianne Zwicknagl in 1957. They had three children: Max Josef, Franz Georg, and Monika, who was member of the Landtag of Bavaria and a Bavarian minister. In 2009 she was elected to the European Parliament.

After the war, he was appointed deputy Landrat (county president) of Schongau by the American occupiers and was involved in founding the local party organization of the Christian Social Union of Bavaria (CSU). He became a member of the first Bundestag (Federal Parliament) in 1949 and, in 1953, Federal Minister for Special Affairs in the second cabinet of Chancellor Konrad Adenauer, in 1955 Federal Minister of Nuclear Energy, and in 1956 defence minister, charged with the build-up of the new Bundeswehr – the youngest man to hold this office at the time. He became chairman of the CSU in 1961.

Former Lockheed lobbyist Ernest Hauser told Senate investigators that Minister of Defence Strauss and his party had received at least $10 million for West Germany's purchase of 900F-104G Starfighters in 1961, which later became part of the Lockheed bribery scandals.

The party and its leader denied the allegations, and Strauss filed a

slander suit against Hauser. As the allegations were not corroborated,

the issue was dropped. Strauss was appointed minister of the treasury again in 1966, in the cabinet of Kurt Georg Kiesinger. In cooperation with the SPD minister for economy, Karl Schiller,

he developed a groundbreaking economic stability policy; the two

ministers, quite unlike in physical appearance and political background,

were popularly dubbed Plisch und Plum, after two dogs in a 19th century cartoon by Wilhelm Busch. After the SPD was able to form a government without the conservatives, in 1969, Strauss became one of the most vocal critics of Willy Brandt's Ostpolitik. After Helmut Kohl's first run for chancellor in 1976 failed, Strauss cancelled the alliance between the CDU and

CSU parties in the Bundestag, a decision which he only took back months

later when the CDU threatened to extend their party to Bavaria (where

the CSU holds a political monopoly for the conservatives). In the 1980 federal election,

the CDU / CSU opted to put forward Strauss as their candidate for

chancellor. Strauss had continued to be critical of Kohl's leadership,

so providing Strauss a shot at the chancellery may have been seen as an

endorsement of either Strauss' policies or style (or both) over Kohl's.

But many, if not most, observers at the time believed that the CDU had

concluded that Helmut Schmidt's SPD

was likely unbeatable in 1980, and felt that they had nothing to lose

in running Strauss. Schmidt's easy win was seen by Kohl's supporters as a

vindication of their man, and though the rivalry between Kohl and

Strauss persisted for years, once the CDU / CSU was able to take power in

1982, Kohl was again their leader, where he remained until well after

Strauss's death.

Strauss was the author of a book called The Grand Design in

which he set forth his views of the way in which the future unification

of Europe should be decided. There is much evidence that he was truly

committed to the creation of a United States of Europe.

Strauss visited communist Albania on 21 August 1984, while Enver Hoxha,

the ruler from the end of World War II until his death in 1985, was

still alive. Strauss was one of the few Western leaders, if not the only

one, to visit the isolationist Albania in decades. This fuelled

speculation that Strauss might be preparing the way for diplomatic links

between Albania and West Germany and indeed, relations were established

in 1987.

On 1 October 1988, Strauss collapsed while hunting with Johannes, 11th Prince of Thurn and Taxis in the Thurn and Taxis forests, east of Regensburg. He died in a Regensburg hospital on 3 October without having regained consciousness. Strauss

shaped post - war Germany and polarized the public like few others. He

was a vocal figurehead for conservatives and a skilled rhetorician. His

clearly right - leaning political standpoints and his involvement in

several large scale scandals made him an opponent of more moderate

politicians and the entire political left. Nevertheless, it is seldom

disputed that his policies have contributed to change Bavaria from an

agrarian state to one of Germany's leading industry centers. The CSU,

his former political party that still strongly identifies with his

legacy, has as of today never lost an election in Bavaria, and often

receives vote margins well over 50%. As an aerospace enthusiast, Strauss was one of the driving persons to create Airbus in the 1970s. He served as Chairman of Airbus in the late 1980s, until his death in 1988; he saw the company win a lucrative but controversial (Airbus affair) contract to supply planes to Air Canada just before his death. Munich's new airport, the Franz Josef Strauss Airport, was named after him in 1992.

Strauss was forced to step down as defence minister in 1962 in the wake of the Spiegel scandal. Rudolf Augstein, owner and editor - in - chief of the influential Der Spiegel magazine,

had been arrested on Strauss's request and was held for 103 days.

Strauss was forced to admit that he had lied to the parliament and was

forced to resign, complaining that he was treated like a "Jew who had

dared appear at a Nazi party convention".

From 1978 until his death in 1988, Strauss was minister - president of Bavaria, serving as President of the Bundesrat in

1983 / 84. After his defeat in the 1980 federal election, he retreated

to commenting on federal politics from his safe seat in Bavaria. In the

following years, he was the most visible critic of Kohl's politics in

his own political camp, even after Kohl ascended to the Chancellorship.

In 1983, he was primarily responsible for a loan of 3 billion Deutsche

Mark given to East Germany. This move was widely criticised even during Strauss's lifetime.