<Back to Index>

- Jurist and Prime Minister of Japan Kijūrō Shidehara, 1872

- Composer Girolamo Frescobaldi, 1583

- Emperor of the Byzantine Empire John II Komnenos, 1087

PAGE SPONSOR

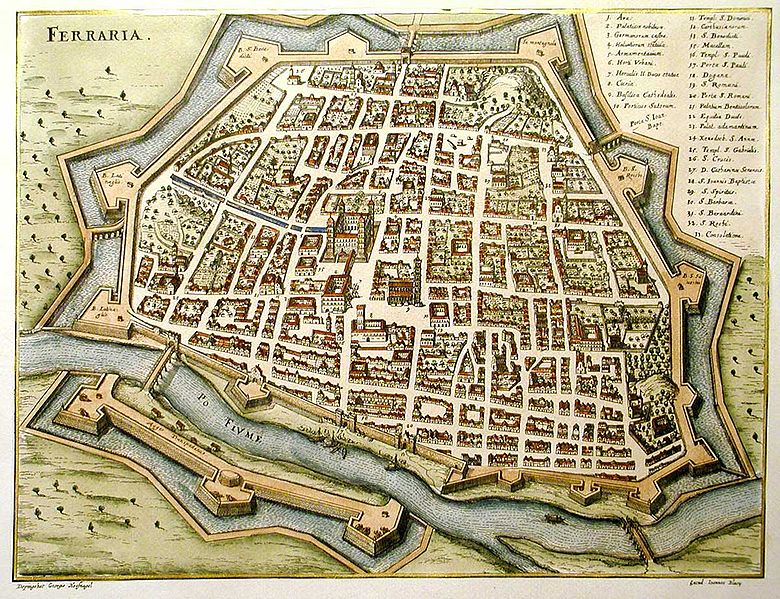

Girolamo Frescobaldi (September, 1583 – March 1, 1643) was a musician from Ferrara, one of the most important composers of keyboard music in the late Renaissance and early Baroque periods. A child prodigy, Frescobaldi studied under Luzzasco Luzzaschi in Ferrara, but was influenced by a large number of composers, including Ascanio Mayone, Giovanni Maria Trabaci, and Claudio Merulo. Girolamo Frescobaldi was appointed “organist” of St. Peter's Basilica, a focal point of power for the Capella Giulia (a musical organisation) from July 21, 1608 until 1628 and again from 1634 until his death. Frescobaldi's printed collections contain some of the most influential music of the 17th century. His work influenced Johann Jakob Froberger, Johann Sebastian Bach, Henry Purcell, and countless other major composers. Pieces from his celebrated collection of liturgical organ music, Fiori musicali (1635), were used as models of strict counterpoint as late as the 19th century.

The composer was born in Ferrara, Italy. His father Filippo was a man of property, possibly an organist, since both Girolamo and his half - brother Cesare became organists. (There is no evidence that the Frescobaldi of Ferrara were related to the homonymous Florentine noble house.) Frescobaldi studied under Luzzasco Luzzaschi, a noted composer of madrigals and an organist at the court of Duke Alfonso II d'Este. Although Luzzaschi's keyboard music is relatively unknown today (much of it has been lost), contemporary accounts suggest he was both a gifted composer and performer, one of the few who could perform and compose for Nicola Vicentino's arcicembalo. Contemporary accounts describe Frescobaldi as a child prodigy who was "brought through various principal cities of Italy"; he quickly gained prominence as a performer and patronage of important noblemen. Composers who visited Ferrara during the period included numerous important masters such as Claudio Monteverdi, John Dowland, Orlande de Lassus, Claudio Merulo, and, most importantly, Carlo Gesualdo.

In his early twenties, Frescobaldi left his native Ferrara for Rome. Reports place Frescobaldi in that city as early as 1604, but his presence can only be confirmed by 1607. He was the church organist at Santa Maria in Trastevere, recorded as “Girolamo Organista”, from January to May of that year. He was also employed by Guido Bentivoglio, the Archbishop of Rhodes, and accompanied him on a trip to Flanders where Bentivoglio had been made nuncio to the court. It was Frescobaldi's only trip outside Italy. Although the court at Brussels was musically among the most important in Europe at the time, there is no evidence of Peeter Cornet's or Peter Philips' influence on Frescobaldi. Based on Frescobaldi's preface to his first publication, the 1608 volume of madrigals, the composer also visited Antwerp, where local musicians, impressed with his music, persuaded him to publish at least some of it. While abroad, Frescobaldi was elected on 21 July 1608 to succeed Ercole Pasquini as organist of St. Peter's Basilica in Rome. Frescobaldi remained in Flanders, however, through the summer and did not return to Rome until 29 October (delaying his arrival with an extended stay in Milan to publish another collection of music, the keyboard Fantasie). He took up his duties on 31 October and held the position, albeit intermittently, until his death. He also joined Enzo Bentivoglio's musical establishment after the latter settled in Rome in 1608, although he grew estranged from his patron after an affair with a young woman. A scandal involving competition between Bentivoglio and the Medici family eventually forced him to leave his position.

Between 1610 – 13 Frescobaldi began to work for Cardinal Pietro Aldobrandini. He remained in their service until after the death of Cardinal Aldobrandini in February of 1621. On February 18, 1613, he married Orsola Travaglini, known as Orsola del Pino. The

couple had five children: Francesco (an illegitimate child born May 29,

1612), Maddalena (an illegitimate child born July 22, 1613), Domenico

(November 8, 1614, poet and art collector), Stefano (1616/7), and

Caterina (September 1619). In October of 1614, Frescobaldi was approached by an agent of the Duke of Mantua, Ferdinando I Gonzaga.

Frescobaldi was given such a good offer he agreed to enter his employ.

However, at his arrival in Mantua the reception was so cold that

Frescobaldi returned to Rome by April 1615. He continued publishing his music: two editions of the first book of toccatas and a book of ricercars and canzonas appeared in 1615. In addition to his duties at the Basilica and the Aldobrandini

establishment, Frescobaldi took pupils and occasionally worked at other

churches. The period from 1615 - 28 was Frescobaldi’s most productive

time. His major works from this period were instrumental pieces

including: a second version of the first book of toccatas (1615-6),

ricercars and canzonas (1615), the cappricios (1624), the second book of

toccatas (1627), and a volume of canzonas for one to four instruments

and continuo (1628).

St. Peter’s Basilica gave Frescobaldi permission to leave Rome November 22, 1628. Girolamo moved to Florence, Italy, into the service of the Grand Duke of Tuscany, a Medici. During his sojourn there he was the highest paid musician and served as the organist of the Florence baptistery for a year. He

stayed in the city until 1634; the period resulted in, among other

things, the publication of two books of arias (1630). The composer

returned to Rome in April 1634, having been summoned into the service of

the powerful Barberini family, i.e. Pope Urban VIII Barberini, the highest prize offered to any musician. He continued working at St. Peter's, and was also employed by Cardinal Francesco Barberini, who also employed the famous lutenist Johannes Hieronymus Kapsberger. Frescobaldi published one of his most influential collections, Fiori musicali, in 1635, and also produced reprints of older collections in 1637. No

other prints followed (although a collection of previously unpublished

works appeared in 1645, and in 1664 Domenico Frescobaldi still possessed

pieces by his father that were never published). Frescobaldi died on 1

March 1643 after an illness that lasted for 10 days. He was buried in Santi Apostoli,

but the tomb disappeared during a rebuilding of the church in late 18th

century. A grave bearing his name and honoring him as one of the

fathers of Italian music exists in the church today. Frescobaldi

was the first of the great composers of the ancient

Franco - Netherlandish - Italian tradition who chose to focus his creative energy on instrumental composition. Frescobaldi brought a wide range of emotion to the relatively unplumbed depths of instrumental music. Keyboard music occupies the most important position in Frescobaldi's extant oeuvre. He

published eight collections of it during his lifetime, several were

reprinted under his supervision, and more pieces were either published

posthumously or transmitted in manuscripts. The

ensemble canzonas of 1634 are most likely the most thoroughly revised

of Frescobaldi’s works. Of the forty pieces within the collection, ten

were replaced and another sixteen were revised to various degrees. This

extensive editing attests to Frescobaldi’s ongoing interest in the

utmost perfection of his pieces and collections. Frescobaldi’s compositional canon began with his 1615 publications. One of the publications issued in 1615 was Ricercari, et canzone. This work returned to the old fashioned, pure style of ricercar. Fast

note values and triple meter were not allowed to detract from the purity

of style. A second publication of 1615 was the Toccate e partite which

established expressive keyboard style. Frescobaldi did not obey the

conventional rules for composing, ensuring no two works had a similar

structure. From

1615 - 28, Frescobaldi’s publications connect him with the Congregazione

exactly when the group’s activities determined the Roman musical trends. Frescobaldi’s

next stream of compositions expanded their artistic range beyond the

keyboard music that he had focused on previously. Frescobaldi's

next four publications after 1627 were composed for instrumental and

vocal ensembles in both sacred and secular genres. The

collections of thirty sacred works of 1627 and forty ensemble canzonas

of 1628 are structural opposites. However, both are written in a more

traditional style that makes them appropriate for church use. The Arie musicali,

published in 1630, were probably composed earlier while Frescobaldi was

in Rome. These two volumes utilize keyboard pairs, the

romanesca / ruggiero and the ciaconna / passacaglia, within the vocal mode. In 1635 Frescobaldi published Fiori musicali. This group of works is his only composition devoted to church music and his last collection containing completely new pieces. The Fiori experiments with many types of genres within the liturgical confines of a mass.

Almost all of the genres practiced by Frescobaldi are present within

this collection except for the popular style. Frescobaldi cultivated the old form of organ improvisation on a Gregorian chant cantus firmus that is best displayed within the Fiori muscali. The organ alternated with the choir on versets and improvised in a contrapuntal style. Works from the 1634 collection Fiori musicali were still used as models of strict counterpoint in the 18th and 19th centuries. Aside from Fiori musicali, Frescobaldi's two books of toccatas and partitas (1615 and 1627) are his most important collections. His

toccatas could be used in masses and liturgical occasions. These

toccatas served as preludes to larger pieces, or were pieces of

substantial length standing alone. The Secondo libro di toccata written

in 1627 stretches the conception of the genres included in the first

book of toccatas. More variety is introduced with different rhythmic

techniques and four organ pieces. Both books open with a set of twelve toccatas written in a flamboyant improvisatory style and alternating fast - note runs or passaggi with more intimate and meditative parts, called affetti,

plus short bursts of contrapuntal imitation. Virtuosic techniques

permeate the music and make some of the pieces challenging even for

modern performers — Toccata IX from Secondo libro bears

an inscription by the composer: "Non senza fatiga si giunge al fine",

"Not without toil will you get to the end." Such short remarks appear

also in works from Fiori musicali;

one of these refers to a fifth voice that is to be sung by the

performer at key moments during a ricercar, and the key moments are left

to the performer to find. Frescobaldi's famous note for this piece is

""Intendami chi puo che m'intend' io" — "Understand me, [who can,] as long

as I can understand myself". The concept is yet another illustration of

Frescobaldi's innovative, bold approach to composition. Although Frescobaldi was influenced by numerous earlier composers such as the Neapolitans Ascanio Mayone and Giovanni Maria Trabaci and the Venetian Claudio Merulo,

his music represents much more than a summary of its influences. Aside

from his masterful treatment of traditional forms, Frescobaldi is

important for his numerous innovations, particularly in the field of tempo:

unlike his predecessors, he would include in his pieces sections in

contrasting tempi, and some of his publications include a lengthy preface detailing tempo - related aspects of performance. In effect, he made a compromise between the ancient white mensural notation with a rigid tactus and the modern notion of tempo. Although this idea was not new (it was used by, for example, Giulio Caccini),

Frescobaldi was among the first to popularize it in keyboard music.

Frescobaldi also made substantial contributions to the art of variation;

he may have been one of the first composers to introduce the

juxtaposition of the ciaccona and passacaglia into the music repertory,

as well as the first to compose a set of variations on an original theme

(all earlier examples are variations on folk or popular melodies). Frescobaldi

showed an increasing interest in composing intricate works out of

unrelated individual pieces during his last years of composing. The last work Frescobaldi composed, Cento partite sopra passacagli, was his most impressive creative work. The Cento displays Frescobaldi’s new interest in combining different pieces that were first written independently. The

composer's other works include collections of canzonas, fantasias,

capriccios, and other keyboard genres, as well as four prints of vocal

music (motets and arias; one book of motets is lost) and one of ensemble

canzonas. Contemporary

critics acknowledged Frescobaldi as the single greatest trendsetter of

keyboard music of their time. Even critics who did not approve of

Frescobaldi’s vocal works agreed that he was a genius both playing and

composing for the keyboard. Frescobaldi’s music did not lose direct influence until the 1660s, and his works held

influence over the development of keyboard music over a century after

his death. Bernardo Pasquini promoted Girolamo Frescobaldi to the rank

of pedagogical authority. Frescobaldi's pupils included numerous Italian composers, but the most important was a German, Johann Jakob Froberger, who studied with him in 1637 – 41. Froberger's works were influenced not only by Frescobaldi but also by Michelangelo Rossi;

he became one of the most influential composers of the 17th century,

and, similarly to Frescobaldi, his works were still studied in the 18th

century. Frescobaldi's work was known to, and influenced numerous major

composers outside Italy, including Henry Purcell, Johann Pachelbel, and Johann Sebastian Bach.

Bach is known to have owned a number of Frescobaldi's works, including a

manuscript copy of Frescobaldi's Fiori musicali (Venice, 1635), which

he signed and dated 1714 and performed in Weimar the

same year. Frescobaldi's influence on Bach is most evident in his early

choral preludes for organ. Finally, Frescobaldi's toccatas and

canzonas, with their sudden changes and contrasting sections, may have

inspired the celebrated stylus fantasticus of the North German organ school.