<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Alberto Pedro Calderón, 1920

- Writer Hans Theodor Woldsen Storm, 1817

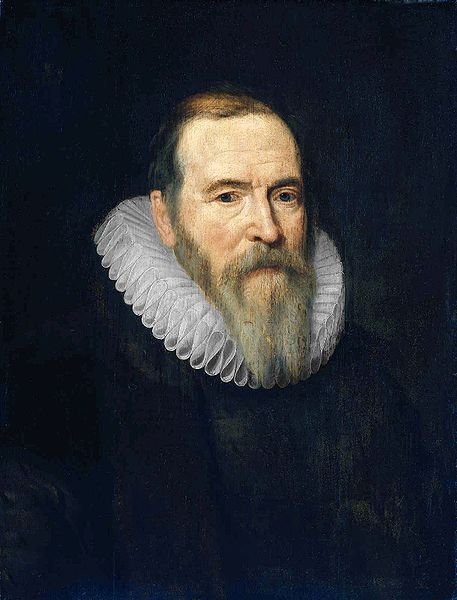

- Land's Advocate of Holland Johan van Oldenbarnevelt, 1547

PAGE SPONSOR

Johan van Oldenbarnevelt, Lord of Berkel en Rodenrijs (1600), Gunterstein (1611) and Bakkum (1613) (September 14, 1547, Amersfoort – May 13, 1619, The Hague) was a Dutch statesman who played an important role in the Dutch struggle for independence from Spain.

Van Oldenbarnevelt studied law at Leuven, Bourges, Heidelberg and Padua, and traveled in France and Italy before settling in The Hague. He was a Calvinist, he supported William the Silent in his revolt against Spain, and fought in William's army. On March 16, 1586, van Oldenbarnevelt, in succession to Paulus Buys, became Land's Advocate of Holland for the States of Holland,

an office he held for 32 years. This great office, given to a man of

commanding ability and industry, offered unbounded influence in a

multi - headed republic without any central executive authority. Though

nominally the servant of the States of Holland, Oldenbarnevelt made

himself the political personification of the province which bore more

than half the entire charge of the union. As mouthpiece of the

States - General, he practically dominated the assembly. In a brief

period, he became entrusted with such large and far - reaching authority

in all details of administration, that he became the virtual Prime minister of the Dutch republic. During

the two critical years following the withdrawal of Leicester, the

Advocate's statesmanship kept the United Provinces from collapsing under

their own inherent separatist tendencies. This prevented the United

Provinces from becoming an easy conquest for the formidable army of Alexander of Parma. Also of good fortune for the Netherlands, the attention of Philip II of Spain was at its greatest weakness, instead focused on a contemplated invasion of England.

Spain's lack of attention coupled with the United Province's lack of

central, organized government allowed Oldenbarnevelt to gain control of

administrative affairs. His task was made easier by receiving

whole - hearted support from Maurice of Nassau, who, after 1589, held the

office of Stadholderate of five provinces. He was also Captain - General and Admiral of the Union. The

interests and ambitions of Oldenbarnevelt and Maurice did not clash.

Indeed, Maurice's thoughts were centered on training and leading armies,

and he had no special capacity as a statesman or desire for politics.

Their first rift between them came in 1600, when Maurice was forced against

his will by the States - General, under the Advocate's influence, to

undertake a military expedition to Flanders. The expedition was saved from disaster by desperate efforts that ended in victory at the Nieuwpoort. In 1598, Oldenbarnevelt took part in special diplomatic missions to Henry IV and Elizabeth, and again in 1605 in a special mission sent to congratulate James I on his accession. The opening of negotiations by Albert and Isabel in 1606 for a peace or long truce led to a great division of opinion in the Netherlands. The

archdukes having consented to treat with the United Provinces as free

provinces and states over which they had no pretensions, Oldenbarnevelt,

who had with him the States of Holland and the majority of the Regenten patriciate throughout the county, was for peace, provided that liberty of trading was conceded. Maurice and his cousin William Louis, stadholder of Friesland,

with the military and naval leaders and the Calvinist clergy, were

opposed to it, on the ground that the Spanish king was merely seeking a

repose to recuperate his strength for a renewed attack on the

independence of the Netherlands. For some three years the negotiations

went on, but at last after endless parleying, on 9 April 1609, a truce

for twelve years was concluded. All the Dutch demands were directly or

indirectly granted, and Maurice felt obliged to give a reluctant and

somewhat sullen assent to the favorable conditions obtained by the firm

and skillful diplomacy of the Advocate. The

immediate effect of the truce was a strengthening of Oldenbarnevelt's

influence in the government of the Dutch Republic, now recognized as a

free and independent state; external peace, however, was to bring with

it internal strife. For some years there had been a war of words between

the religious parties, the strict Calvinist Gomarists (or Contra - Remonstrants) and the more liberal Arminians. In 1610 the Arminians, henceforth known as Remonstrants, drew up a petition, known as the Remonstrance, in which they asked that their tenets (defined in the Five Articles of Remonstrance)

should be submitted to a national synod, summoned by the civil

government. It was no secret that this action of the Arminians was

taken with the approval and connivance of Oldenbarnevelt, who was an

upholder of the principle of toleration in religious opinions. The

Gomarists in reply drew up a Contra - Remonstrance in seven articles,

and called for a purely church synod. The whole land was henceforth

divided into Remonstrants and Contra - Remonstrants; the States of

Holland under the influence of Oldenbarnevelt supported the former, and

refused to sanction the summoning of a purely church synod (1613). They

likewise (1614) forbade the preachers in the Province of Holland to

treat the disputed subjects from their pulpits. Obedience was difficult

to enforce without military help. Riots broke out in certain towns, and

when Maurice was appealed to, as Captain ‐ General, he declined to act.

Though in no sense a theologian, he then declared himself on the side

of the Contra - Remonstrants, and established a preacher of that

persuasion in a church in The Hague (1617). The

Advocate now took a bold step. He proposed that the States of Holland

should, on their own authority, as a sovereign province, raise a local

force of 4000 men (waardgelders) to keep the peace. The

States - General, meanwhile, by a bare majority (4 provinces to 3) agreed

to the summoning of a national church synod. The States of Holland,

also by a narrow majority, refused their assent to this, and passed on

August 4, 1617 a strong resolution (Scherpe Resolutie) by which

all magistrates, officials and soldiers in the pay of the province were

on pain of dismissal required to take an oath of obedience to the States

of Holland, and were to be held accountable not to the ordinary

tribunals, but to the States of Holland. The

States ‐ General of the Republic saw this as a declaration of sovereign

independence on the part of Holland, and decided to take action. A

commission was appointed, with Maurice at its head, to compel the

disbanding of the waardgelders. On 31 July 1618 the Stadholder, at the head of a body of troops,

appeared at Utrecht, which had thrown in its lot with Holland. At his

order the local militias laid down their arms. His

progress through the towns of Holland met with no military opposition.

The States' sovereignty party was crushed without a battle being fought. On 23 August 1618, by order of the States - General, Oldenbarnevelt and his chief supporters, Hugo Grotius, Gilles van Ledenberg, Rombout Hogerbeets and Jacob Dircksz de Graeff, were arrested or lost their political positions in government. Oldenbarnevelt

was, with his friends, kept in strict confinement until November of

that year, and then brought for examination before a commission

appointed by the States - General. He appeared more than 60 times before

the commissioners and the whole course of his official life was severely

examined. During the period of inquest, he was neither allowed to

consult papers nor put his defense in writing. On

20 February 1619, Oldenbarnevelt was arraigned before a special court

of twenty - four members, only half of whom were Hollanders, and nearly

all of whom were personal enemies. This ad hoc judicial

commission was necessary, because, unlike in the individual provinces,

the federal government did not have a judicial branch. Normally the

accused would be brought before the Hof van Holland or the Hoge Raad van Holland en Zeeland, the highest courts in the provinces of Holland and Zeeland; however, in this case, the alleged crime was against the Generaliteit,

or federal government, and required adjudication by the States - General,

acting as highest court in the land. As was customary in similar

cases (for instance, the later trial of the judges in the case of the Amboyna massacre),

the trial was delegated to a commission. Of course, the accused

contested the competence of the court, as they contested the residual

sovereignty of the States - General, but their protest was disregarded. It was in fact a kangaroo court,

and the stacked bench of judges on Sunday, 12 May 1619, pronounced a

death sentence on Oldenbarnevelt. On the following day, the old

statesman, at the age of seventy-one, was beheaded in the Binnenhof, in The Hague. Oldenbarnevelt's last words to the executioner were purportedly: "Make it short, make it short." The

States of Holland noted in their Resolution book on 13 May that

Oldenbarnevelt had been: "…a man of great business, activity, memory and

wisdom – yes, extra - ordinary in every respect." They added the cryptic sentence Die staet siet toe dat hij niet en valle which probably should be understood as a free Dutch translation of the old dictum sic transit gloria mundi, or possibly translated as "pride comes before the fall".

Oldenbarnevelt was married in 1575 to Maria van Utrecht. He left two sons; Reinier van Oldenbarnevelt, lord of Groeneveld and Willem van Oldenbarnevelt,

lord of Stoutenburg, and two daughters. A conspiracy against the life

of Maurice, in which both sons of Oldenbarnevelt took part, was

discovered in 1623. Stoutenburg, who was the chief accomplice, made his

escape and entered the service of Spain; Groeneveld was executed.

The Nederland Line ship Johan van Oldenbarnevelt carried his name from 1930 to 1963.

He served as a volunteer for the relief of Haarlem (1573) and again at Leiden (1574). In 1576 he obtained the important post of pensionary of Rotterdam, an office which carried with it official membership of the States of Holland.

In this capacity his industry, singular grasp of affairs, and

persuasive powers of speech speedily gained for him a position of

influence. He was active in promoting the Union of Utrecht (1579) and the offer of the countship of Holland and Zeeland by William (prevented by Williams death in 1584). He was a fierce opponent of the policies of the Earl of Leicester, the governor ‐ general at the time, and instead favoured Maurice of Nassau,

a son of William. Leicester left in 1587, leaving the military power in

the Netherlands to Maurice. During the governorship of Leicester, Van

Oldenbarnevelt was the leader of the strenuous opposition offered by the

States of Holland to the centralizing policy of the governor.