<Back to Index>

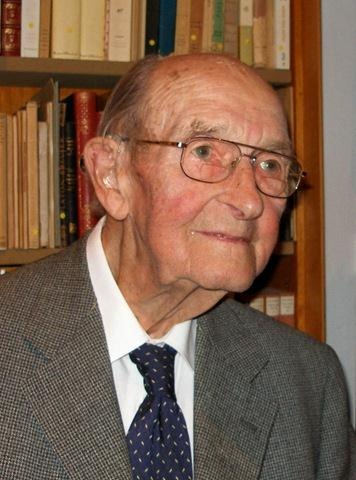

- Jurist and Minister President of Baden - Württemberg Hans Karl Filbinger, 1913

- Writer Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay, 1876

- Prime Minister of Denmark Jens Otto Krag, 1914

PAGE SPONSOR

Hans Karl Filbinger (15 September 1913 – 1 April 2007) was a conservative German politician and a leading member of the Christian Democratic Union in the 1960s and 1970s, serving as the first chairman of the CDU Baden - Württemberg and vice chairman of the federal CDU. He was Minister President of Baden - Württemberg from 1966 to 1978 and as such also chaired the Bundesrat in 1973 - 74. He had to resign as minister president and party chairman after allegations about his role as a navy lawyer and judge in the Second World War. While the CDU Baden - Württemberg elected him honorary chairman — a position he held until his death — he remained a controversial figure. He also founded the conservative think tank Studienzentrum Weikersheim, which he chaired until 1997.

Filbinger was born on 15 September 1913 in Mannheim.

Filbinger studied law and economics in Freiburg, Munich, and Paris. Having earned his doctorate in 1939 with the dissertation "Limits to majority rule in stock and corporation law", he worked as a lecturer at the University of Freiburg. In 1940 he passed his final examination.

Filbinger, a Catholic, was married to Ingeborg

Breuer and had four daughters and a son.

Filbinger first came into contact with Nazi organisations as a student. He was a member of the Jugendbund Neudeutschland (Youth Federation New - Germany), which he had joined in grammar school. As this Catholic students' federation with political leanings to the Centre Party opposed their being integrated into the Hitler Youth, it was banned. Filbinger, who was a leading member in the district of Northern Baden, in April 1933 called his fellow members to continue their work with their previous intentions and issue a programme for the upcoming future. As a result, the NSDAP deemed him "politically unreliable".

On 1 June 1933, Filbinger joined the Sturmabteilung (SA), and

later also the National Socialist students federation,

but largely remained an inactive member. Attorney

General Brettle advised Filbinger, as he was applying

for his first examination in January 1937, that he

could not expect to be admitted to the Referendariat,

the preparatory service required for future state

employees without having cleared himself from these

political complaints. Seeing

himself barred from the second examination and hence

blocked from any further professional career,

Filbinger asked to be admitted to NS party membership

in spring.

In 1940, Filbinger was conscripted into the

German Navy. He was promoted to the rank of Oberfähnrich and later

to that of lieutenant. In 1943 he was ordered to

enter the military legal department - according to his

own account, against his will. Two attempts at

avoiding this by volunteering for submarine squads

didn't succeed. Filbinger

served in the legal department until the end of the

war in 1945. This period of his life was later raised

to prominence in the Filbinger

affair.

During that time he was a member of the Freiburg circle,

a group of Catholic intellectuals centred around the

publisher Karl Färber.

Filbinger used his periods of leave to return to

Freiburg and attend lectures by Reinhold Schneider, a writer critical

of the Nazi regime.

Without his knowledge, two of the conspirators of the July 20 Plot — Karl Sack and Berthold Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg—

recommended Filbinger for employment after a

successful coup, adding that one could always rely on

Filbinger's "principled anti - Nazi stance and

loyalty".

In 1946, Filbinger resumed his academic work

at the university of Freiburg, subscribing to Walter Eucken's ordoliberalism, and settled down as

lawyer. In 1947, he was coopted into the International

anti - trust commission, chaired by Eucken and

Karl Gailer.

In 1951 Filbinger joined the Christian Democratic Union and rose

to be chairman of the CDU of Southern Baden. In 1953,

Filbinger was elected to the city council of Freiburg.

In 1958, minister - president Gebhard Müller appointed

him an honorary state council. As such he was a member

of the state government, mainly concerned with the

interests of Southern Baden in the young state of Baden - Württemberg. In 1960,

Filbinger was appointed Minister of the Interior.

In the same year, he was elected into the state

parliament of Baden - Württemberg, in which he

represented the city of Freiburg. He remained a member

of parliament until 1980.

In 1966, minister - president Kurt Georg Kiesinger was

elected Chancellor of Germany and

Filbinger succeeded him as minister - president of

Baden - Württemberg. At that time, the CDU's

coalition partner FDP broke

with the CDU in order to form a government with the SPD. Dramatic negotiations resulted in

Filbinger forming a CDU - SPD government, mirroring

the Federal Great

Coalition.

The Great Coalition continued after the state

elections of 1968 and went on to reform the

administrative system. This reform merged many towns

and districts to create more viable units. According

to Filbinger, towns are "true sources of power for the

state and provide the citizen with the feeling ... of

having a home". The results transcended the historical

borders of the historic regions of Baden and Württemberg. The two regions had

only been united in 1952 after a referendum. Their

relationship had never been easy and the opposition

against the new "South - West State" remained strong

in Baden. Proponents of Baden's independence raised

concerns about the legitimacy of the 1951 referendum

because of the controversial voting modalities. In

1956, the Federal Constitutional Court declared the

modalities and the merger of the states legal but

added that the will of the people of Baden had indeed

been glossed over by political machinations. The

decision had no immediate consequences until Filbinger

became Minister - President. He himself hailed from

Baden and after the court had reiterated its earlier

verdict in 1969, the Filbinger administration in 1970

held a second referendum in Baden, which resulted in

an overwhelming approval of the merger. Filbinger has

been dubbed "architect of Baden - Württemberg's

unity" for this.

Filbinger also pushed his party, that still

was organized as four distinct regional parties to

unite into a single CDU of Baden - Württemberg

and was duly elected the first chairman.

In the 1972 state elections, the Filbinger's

CDU achieve 52,9% of the vote, gaining an absolute

majority for the first time. In 1976, campaigning

under the slogan "Freedom instead of socialism", he

increased his party's vote to a hitherto unsurpassed

56,7%.

Filbinger was a staunch opponent of leftist

tendencies in politics and the universities, and

figured prominently in the struggle against terrorism. Against nationwide trends,

he opposed comprehensive schools and expanded the

state's tripartial school system (Hauptschule,

Realschule, Gymnasium) and also vocational schools.

As minister - president of Baden -

Würrtemberg, he was President of the Bundesrat, the representation of the

states on the federal level, from 1973 to 1974.

During the 1970s, Filbinger enjoyed a

tremendous popularity as a patriarchal figure. He was

elected a member of federal CDU executive board and

also deputy chairman. Analysts even deemed him a

possible candidate for the presidential elections in 1979,

when his career suddenly ended in 1978 due to the Filbinger

affaire, an event from which his reputation has

never recovered.

The first criticism of Filbinger's war time

record dates back to 10 April 1972. Two weeks before

the Baden - Württemberg state elections, the Der Spiegel magazine

published one of Filbinger's verdicts. On 29 May 1945,

Filbinger presided at the trial against artillery man

Petzold and sentenced him to six months imprisonment

for incitement of discontent, refusal of obedience and

resistance. In an editorial, the Spiegel also

claimed that, based on Petzold's memories, Filbinger

had referred to Hitler as "our beloved Führer ...

who has brought the fatherland back up". Filbinger

immediately reacted by filing a law suit against the Spiegel,

demanding that the Spiegel desist from making such a

claim. The court decided in favour of Filbinger, since

it found Petzold an unreliable witness and the alleged

quote in conflict with Filbinger's other utterances

and actions. Nonetheless, allegations against

Filbinger continued at various occasions, e.g. in 1974

when Filbinger as President of the Bundesrat spoke at

the tricennial of the July 20 Plot, or in

1975 during the debate about a nuclear facility at Wyhl. Debaters often twisted or

neglected the existing evidence or confused the

circumstance, Petzold's anti - Nazi stance in

particular, with the actual verdict.

Filbinger's verdict against Petzold was

especially criticized for having occurred after the

surrender of the German military on 8 May 1945.

However, the British military command had charged

German officers in Norway with maintaining order among

the German prisoners - of - war. Later the Petzold

trial was confused with other cases involving

Filbinger, creating the legend that Filbinger had

sentenced a soldier to death for having spoken out

against Nazism after German surrender.

The controversy was brought to the boiling

point by the controversial German author Rolf Hochhuth. On 17 February 1978 the

German weekly Die Zeit published

a preview from Hochhuth's novel A Love

in Germany (published

October 1978), the backbone of which was the case of

seaman Walter Gröger. Hochhuth accused Filbinger

of having "participated" in four death sentences as a

navy lawyer. The Petzold trial, though not involving a

death sentence, Hochhuth deemed "outrageous" for

having been held after the end of war. In his

allegations, Hochhuth called Filbinger "such a

dreadful lawyer, so that one has to presume that ...

he is only living in freedom because of the silence of

those who knew him." As in the previous case,

Filbinger filed a law suit against Hochhuth and Die Zeit,

seeking to have the claim quoted above banned as

libel. In contrast to the previous case, the court did

not take the incriminated sentence as a unit but

analysed and judged it bit by bit. On June 13, 1978

the court decided that Hochhuth's claims about illegal

behaviour were indeed a libellous charges and banned

the author from repeating them. However, The term "a

dreadful lawyer" was deemed a judgement of opinion

protected by freedom of speech. The court has been

criticized for mistaken the causal connection between

the two statements for a simple addition. Filbinger

abstained from appealing the court's decision, and

though Hochhuth did not repeat his "illegality"

charges (and later even claimed that no one ever made

such charges) the other allegation were echoed and

variegated by the media.

During his stint as a Navy lawyer, Filbinger

had been involved in 230 cases, of which six were of a

capital nature. In three of these cases, Filbinger was

the attorney for the prosecution, in two cases he had

been the presiding judge and in one case he had

interfered from outside.

In May 1943 several seamen employed in

clearing up the scene after an air raid on Kiel were

accused of having stolen some petty goods from a drug

store. Filbinger, as prosecutor, demanded the death

penalty for the ringleader Krämer and the judge

did sentence Krämer to death. After the verdict,

Filbinger again interrogated the seaman about the

incident and afterwards wrote a report putting the

condemned man in a positive light. Filbinger appended

this report to the verdict that had to be sent to the

superior commander for confirmation and as the

commander asked Filbinger to comment on the question

whether the man should be pardoned, the prosecutor

made the case for commuting the death penalty into a

prison sentence. The commander agreed and sent

Krämer into a punitive camp. Filbinger himself

called his actions "an act of artifice, of

manipulation, a lie, without a doubt".

The second case was the case on which

Hochhuth's novel was based. The seaman Walter

Gröger, deployed to Norway, had planned to desert

and flee to Sweden with his Norwegian lover. The

couple was found out and arrested and Gröger

sentenced to eight years of prison. However, the

commander of the fleet denied confirmation, returned

the case to the Oslo court martial and ordered the

prosecution to demand the death penalty. On the day of

the trial, the original prosecutor, who already had

pleaded for the death penalty, was prevented

participating and Filbinger, who hadn't been involved

in the case, was appointed prosecutor. According to

the Admiral's orders, Filbinger demanded the death

penalty and the court sentenced the seaman to death. Admiral Dönitz rejected a

plea for pardon. On 16 March 1945 Gröger was

executed and, according to military custom, Filbinger

supervised the execution.

In two cases Filbinger saved opponents of the

regime from execution: He interfered in the

confirmation process of the case of military chaplain

Möbius, who had been sentenced to death for a

political statement. The case was reopened in spring

1945 and Möbius subsequently acquitted. As

prosecutor in the case against Lieutenant Forstmeier,

who had made some remarks about the July 20 Plot, he

influenced the witnesses to testimonies, that could be

interpreted in the defendant's favour, prolonged the

proceedings and obtained a verdict of demotion and imprisonment on

parole. Forstmeier was supposed to be sent to

frontline combat, but the end of the war prevented

this.

Finally, Filbinger issued two death sentences

as a Navy judge: On 9 April, the Oslo court martial

chaired by Filbinger dealt with the case of four

seaman, who had killed their commanding officer and

fled to Sweden. In absentia, the court sentenced them

to death for murder and desertion. (In 1952, one of

the seamen was again brought to trial and sentenced to

ten years in prison). On 17 April 1945, Filbinger

chaired the absentia trial against an Oberststeuermann

who had taken his boat and fourteen seamen to Sweden

and sentenced the officer to death for desertion and undermining morale. Both verdicts were

issued in absentia and could not reach the defendants.

These two death sentences have been explained as an

attempt of avoiding a breaking down of military

discipline even at the end of the war, especially

since the Navy was involved in evacuating two million

Germans from East Prussia that was

encircled by the Red Army.

According to Veteran FAZ editor

Günter Gillessen, who reviewed the case in 2003,

the facts paint a picture different from that of a

bloodthirsty and unrepentant Nazi judge, a view

confirmed by Adolf Harms, who worked as a judge

alongside Filbinger, including the Gröger case,

and described Filbinger as "no fierce dog",

"definitely not a Nazi" and as someone with a

decidedly negative attitude towards the then current

political leadership". It should be

noted that Harms has been described by some as a

"Scharfmacher", a baiter.

Filbinger was not only criticized for his

actions during the war, but also for his reactions to

the allegations in 1978: In his first reactions to the

allegations, Filbinger had claimed that he had "never

issued a single death sentence", which was later

contradicted by the revelation of the two in

absentia cases

from April 1945. That

Filbinger recalled the two death sentences of 1945

only during the controversy in 1978 seemed incredible

and outrageous to many. Filbinger explained this by

characterizing the verdicts as "phantom verdicts" with

no further consequences for the absent defendants.

Another issue revolves around the sentence "Was

damals rechtens war, kann heute nicht Unrecht sein" ("What was

lawful then, cannot be unlawful today."). This comment

was part of an interview the Spiegel had

conducted with Filbinger on 15 May 1978. The Spiegel

interpreted the quote as a justification of Nazi laws,

whereas Filbinger had referred to the military penal

code of 1872, that was in force throughout the Second

World War. Filbinger complained that his quote had

been edited and taken out of context and his then

spokesman Gerhard Goll, who had been present during

the interview, called the magazine's interpretation

"not only untrue but also an infamy". Goll stated that

Filbinger was referring in particular to the fact that

all nations in 1945 considered the death penalty as an

adequate and necessary deterrent against desertion,

whereas he had always considered and labelled the Nazi

state as a "tyranny of injustice". Still, the quote as

originally published stuck with Filbinger and has been

the basis of much of the recurring criticism. Since

then Spiegel, Zeit and other

media have repeated the controversial interpretations,

leading to letters of protest by Filbinger. In 1991,

the Zeit was

forced by court injunction to publish

corrections.

Filbinger's critics have been criticized for

violating the presumption of innocence and for

putting their adversary in a vicious circle, in which a rejection

of allegations is taken as a confirmation of guilt.

Filbinger has been criticized for not

enquiring about other cases after the first

allegations, for not being forthcoming enough or for

placing too much emphasis on the legal dimension of

the allegations.

He also has been criticized for not uttering regret

for his involvement or sympathy for Gröger,

though he explicitly agreed with a comment by the

judge presiding over his 1978 libel case: "The verdict

against Gröger is regrettable and can only be

explained by the one word: war. Every war is

gruesome!"

After CDU politicians had joined in the

criticism, Filbinger resigned as minister - president

on 7 August 1978, and also as chairman of the CDU

Baden - Württemberg. In both positions, he was

succeed by Lothar Späth. Despite this, the

CDU Baden - Württemberg appointed him honorary

chairman in 1979, which he remained until his death.

Filbinger also had to relinquish his offices in the

federal party, resigning as deputy chairman in 1978

and giving up his seat on the executive board in 1981.

As he resigned from office, Filbinger stated that the

attacks would be revealed as untrue, if they hadn't

been so yet. Some historians and lawyers have agreed

with this, while others dispute this conclusion. The

CDU Baden - Württemberg considers Filbinger as

rehabilitated.

After his withdrawal from politics, Filbinger

in 1979 founded the conservative think tank Studienzentrum

Weikersheim (Weikersheim

Centre of Studies), which he chaired until 1997.

In 1987, Filbinger published his memoirs

titled Die

geschmähte Generation (The

slandered generation), in which he again defended

himself against his critics. In a review of this book,

historian Golo Mann called

the events of 1978 a "masterly orchestrated hunt

against Filbinger".

After the collapse of the GDR in 1989/90, two Stasi lieutenants revealed that they had been involved in the campaign against Filbinger:

- "We have fought against Filbinger actively, that means we have collected material and have leaked forged or manipulated material into the west. The fight against Filbinger was a substantial part of "Action Black", a long lasting campaign against conservatives, CDU/CSU, Fascists."

Stasi document P3333 reveals that Filbinger had been spied on since the end of the 1960s. Note that the use of the word Fascist adheres to usage prevalent in Communist states.

Filbinger's case sparks controversy even to this day.

On 16 September 2003, a day after his 90th birthday, Filbinger was honoured by a reception at Ludwigsburg palace. The 130 guests included most government ministers of Baden - Württemberg and his successors Lothar Späth and Erwin Teufel. Protests accompanied the Ludwigsburg reception and had previously resulted in the cancelling in of a similar reception in Filbinger's home town Freiburg.

Filbinger has been elected to the Federal Convention as a representative of Baden - Würrtemberg's parliament in 1959, 1969, 1974, 1994, 1999, and 2004. The last occasion in 2004 caused controversy, as SPD, Greens, PDS, the German PEN and the Jewish Council protested this choice. However, on 31 March 2004, all candidates, including Filbinger, were unanimously confirmed by all parties in the state parliament, including the SPD and Green groupings.

Filbinger died on 1 April 2007 in Freiburg im Breisgau.

On 11 April 2007, Günther Oettinger, the current Minister President of Baden - Württemberg, held a controversial eulogy during the memorial service for his predecessor. In his speech Oettinger described Filbinger as "not a National - Socialist" but "an opponent of the Nazi regime", who could flee the constraints of the regime as little as million others". About Filbinger's role as navy judge, Oettiner pointed out that no one lost his life because of a verdict by Filbinger and had not the power and freedom supposed by his critics. Oettinger was subsequently accused by politicians and the media of diminishing the significance of the Nazi dictatorship. German Chancellor Angela Merkel reacted with public admonishment, stating that she would have preferred if "the critical questions" would have been raised. Oettinger was also criticized by opposition politicians and the Jewish Council; some of his critics even called for his demission. Oettinger at first defended his speech but added that he regretted any "misunderstanding" about his eulogy, but did not withdraw his comments on Filbinger's past. However, on April 16 he distanced himself from his comments.