<Back to Index>

- Physiologist Stephen Hales, 1677

- Writer and Philosopher Hildegard of Bingen, 1098

- 6th President of Israel Chaim Herzog, 1918

PAGE SPONSOR

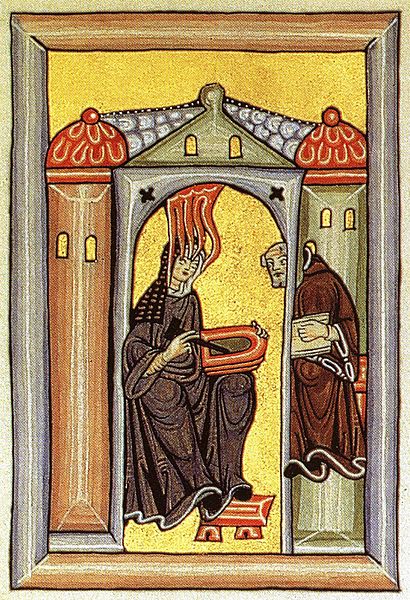

Blessed Hildegard of Bingen (German: Hildegard von Bingen; Latin: Hildegardis Bingensis) (1098 – 17 September 1179), also known as Saint Hildegard, and Sibyl of the Rhine, was a writer, composer, philosopher, Christian mystic, German Benedictine abbess, visionary, and polymath. Elected a magistra by her fellow nuns in 1136, she founded the monasteries of Rupertsberg in 1150 and Eibingen in 1165. One of her works as a composer, the Ordo Virtutum, is an early example of liturgical drama.

She wrote theological, botanical and

medicinal texts, as well as letters, liturgical songs,

poems, and arguably the oldest surviving morality play, while supervising

brilliant miniature Illuminations.

Hildegard of Bingen's date of birth is uncertain. It has been concluded that she may have been born in the year 1098. Hildegard was raised in a family of free nobles. She was her parents' tenth child, sickly from birth. In her Vita, Hildegard explains that from a very young age she had experienced visions. Perhaps due to Hildegard's visions, or as a method of political positioning, Hildegard's parents, Hildebert and Mechthilde, offered her as a tithe to the church. The date of Hildegard's enclosure in the church is contentious. HerVita tells us she was enclosed with an older nun, Jutta, at the age of eight. However, Jutta's enclosure date is known to be in 1112, at which time Hildegard would have been fourteen. Some scholars speculate that Hildegard was placed in the care of Jutta, the daughter of Count Stephan II of Sponheim, at the age of eight, before the two women were enclosed together six years later. There is no written record of the twenty - four years of Hildegard's life that she was in the convent together with Jutta. It is possible that Hildegard could have been a chantress and a worker in the herbarium and infirmarium. In any case, Hildegard and Jutta were enclosed at Disibodenberg in the Palatinate Forest in what is now Germany. Jutta was also a visionary and thus attracted many followers who came to visit her at the enclosure. Hildegard also tells us that Jutta taught her to read and write, but that she was unlearned and therefore incapable of teaching Hildegard Biblical interpretation. Hildegard and Jutta most likely prayed, meditated, read scriptures such as the psalter, and did some sort of handwork during the hours of the Divine Office. This also might have been a time when Hildegard learned how to play the ten - stringed psaltery. Volmar, a frequent visitor, may have taught Hildegard simple psalm notation. The time she studied music could also have been the beginning of the compositions she would later create.

Upon Jutta's death in 1136, Hildegard was unanimously elected as "magistra" of her sister community by her fellow nuns. Abbot Kuno, the Abbot of Disibodenberg, also asked Hildegard to be Prioress. Hildegard, however, wanted more independence for herself and her nuns and asked Abbot Kuno to allow them to move to Rupertsberg. When the abbot declined Hildegard's proposition, Hildegard went over his head and received the approval of Archbishop Henry I of Mainz. Abbot Kuno did not relent, however, until Hildegard was stricken by an illness that kept her paralyzed and unable to move from her bed, an event that she attributed to God's unhappiness at her not following his orders to move her nuns to Rupertsberg. It was only when the Abbot himself could not move Hildegard that he decided to grant the nuns their own monastery. Hildegard and about twenty nuns thus moved to the St. Rupertsberg monastery in 1150, where Volmar served as provost, as well as Hildegard's confessor and scribe. In 1165 Hildegard founded a second convent for her nuns at Eibingen.

Hildegard says that she first saw "The Shade of the Living Light" at the age of three, and by the age of five she began to understand that she was experiencing visions. She used the term 'visio' to this feature of her experience, and recognized that it was a gift that she could not explain to others. Hildegard explained that she saw all things in the light of God through the five senses: sight, hearing, taste, smell, and touch. Hildegard was hesitant to share her visions, confiding only to Jutta, who in turn told Volmar, Hildegard's tutor and, later, secretary. Throughout her life, she continued to have many visions, and in 1141, at the age of 42, Hildegard received a vision she believed to be an instruction from God, to "write down that which you see and hear." Still hesitant to record her visions, Hildegard became physically ill. The illustrations recorded in the book of Scivias were visions that Hildegard experienced, causing her great suffering and tribulations. In her first theological text, Scivias ("Know the Ways"), Hildegard describes her struggle within:

But I, though I saw and heard these things, refused to write for a long time through doubt and bad opinion and the diversity of human words, not with stubbornness but in the exercise of humility, until, laid low by the scourge of God, I fell upon a bed of sickness; then, compelled at last by many illnesses, and by the witness of a certain noble maiden of good conduct [the nun Richardis von Stade] and of that man whom I had secretly sought and found, as mentioned above, I set my hand to the writing. While I was doing it, I sensed, as I mentioned before, the deep profundity of scriptural exposition; and, raising myself from illness by the strength I received, I brought this work to a close – though just barely – in ten years. [...] And I spoke and wrote these things not by the invention of my heart or that of any other person, but as by the secret mysteries of God I heard and received them in the heavenly places. And again I heard a voice from Heaven saying to me, 'Cry out therefore, and write thus!'

Hildegard's Vita was begun by Godfrey of Disibodenberg under Hildegard's supervision.

Attention in recent decades to

women of the medieval Church has

led to a great deal of popular interest in

Hildegard, particularly her music. Between 70 and

80 compositions have survived, which is one of the

largest repertoires among medieval composers.

Hildegard left behind over 100 letters, 72 songs,

70 poems, and 9 books.

One of her better known works, Ordo Virtutum (Play of the Virtues), is a morality play. It is unsure when some of Hildegard’s compositions were composed, though the Ordo Virtutum is thought to have been composed as early as 1151. The morality play consists of monophonic melodies for the Anima (human soul) and 16 Virtues. There is also one speaking part for the Devil. Scholars assert that the role of the Devil would have been played by Volmar, while Hildegard's nuns would have played the parts of Anima and the Virtues.

In addition to the Ordo Virtutum Hildegard composed many liturgical songs that were collected into a cycle called the Symphonia armoniae celestium revelationum. The songs from the Symphonia are set to Hildegard’s own text and range from antiphons, hymns, and sequences, to responsories. Her music is described as monophonic; that is, consisting of exactly one melodic line. Hildegard's compositional style is characterized by soaring melodies, often well outside of the normal range of chant at the time. Additionally, scholars such as Margot Fassler and Marianna Richert Pfau describe Hildegard's music as highly melismatic, often with recurrent melodic units, and also note her close attention to the relationship between music and text, which was a rare occurrence in monastic chant of the twelfth century. Hildegard of Bingen’s songs are left open for rhythmic interpretation because of the use of neumes without a staff. The reverence for the Virgin Mary reflected in music shows how deeply influenced and inspired Hildegard of Bingen and her community were by the Virgin Mary and the saints.

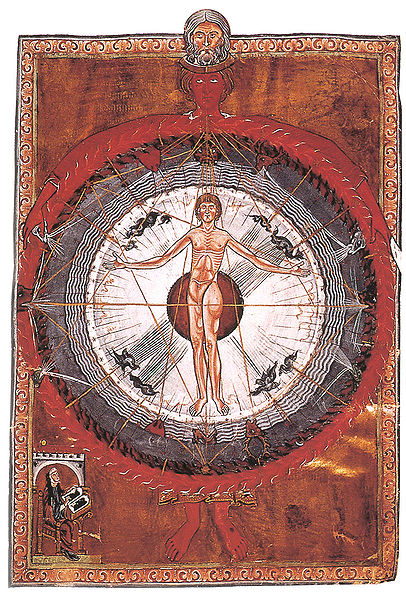

The definition of ‘greenness’ is an earthly expression of the heavenly in an integrity that overcomes dualisms. This ‘greenness’ or power of life appears frequently in Hildegard’s works.

In addition to her music, Hildegard also wrote three books of visions, the first of which, her Scivias ("Know the Way"), was completed in 1151. Liber vitae meritorum ("Book of Life's Merits") and De operatione Dei ("Of God's Activities", also known as Liber divinorum operum, "Book of Divine Works") followed. In these volumes, the last of which was completed when she was about 75, Hildegard first describes each vision, then interprets them through Biblical exegesis. The narrative of her visions was richly decorated under her direction, with transcription assistance provided by the monk Volmar and nun Richardis. The book was celebrated in the Middle Ages, in part because of the approval given to it by Pope Eugenius III, and was later printed in Paris in 1513.

Aside from her books of visions, Hildegard

also wrote her Physica, a text on

the natural sciences, as well as Causae

et Curae. Hildegard of Bingen was well known for

her healing powers involving practical application of

tinctures, herbs, and precious stones. In both texts

Hildegard describes the natural world around her,

including the cosmos, animals, plants, stones, and

minerals. She combined these elements with a

theological notion ultimately derived from Genesis:

all things put on earth are for the use of humans. She is

particularly interested in the healing properties of

plants, animals, and stones, though she also questions

God's effect on man's health. One example

of her healing powers was curing the blind with the

use of Rhine water.

Hildegard also invented an alternative alphabet. The text of her writing and compositions reveals Hildegard's use of this form of modified medieval Latin, encompassing many invented, conflated and abridged words. Due to her inventions of words for her lyrics and a constructed script, many conlangers look upon her as a medieval precursor. Scholars believe that Hildegard used her Lingua Ignota to increase solidarity among her nuns.

Hildegard's musical, literary, and scientific

writings are housed primarily in two manuscripts: the

Dendermonde manuscript and the Riesenkodex. The

Dendermonde manuscript was copied under Hildegard's

supervision at Rupertsberg, while the Riesencodex was

copied in the century after Hildegard's death.

Hildegard's visionary writings maintain that virginity is the highest level of the spiritual life; however, she also wrote about secular life, including motherhood. In several of her texts, Hildegard describes the pleasure of the marital act.

In addition, there are many instances, both in her letters and visions, that decry the misuse of carnal pleasures. She condemns the sins of same - sex couplings and masturbation. After confession, severe repentance expressed in fasting and bodily penance is needed to obtain forgiveness from God for such sins. For instance, in Scivias Book II Vision Six.78:

God united man and woman, thus joining the strong to the weak, that each might sustain the other. But these perverted adulterers change their virile strength into perverse weakness, rejecting the proper male and female roles, and in their wickedness they shamefully follow Satan, who in his pride sought to split and divide Him Who is indivisible. They create in themselves by their wicked deeds a strange and perverse adultery, and so appear polluted and shameful in my sight...

...a woman who takes up devilish ways and plays a male role in coupling with another woman is most vile in My (God's) sight, and so is she who subjects herself to such a one in this evil deed...

...And men who touch their own genital organ and emit their semen seriously imperil their souls, for they excite themselves to distraction; they appear to Me as impure animals devouring their own whelps...

...When a person feels himself disturbed by bodily stimulation let him run to the refuge of continence, and seize the shield of chastity, and thus defend himself from uncleanness. (translation by Mother Columba Hart and Jane Bishop)

Human beings show forth God's creative power, and man and woman have complementary roles in the world.

...When God looked upon the human countenance, God was exceedingly pleased. For had not God created humanity according to the divine image and likeness? Human beings were to announce all God's wondrous works by means of their tongues that were endowed with reason. For humanity is God's complete work.... Man and woman are in this way so involved with each other that one of them is the work of the other. Without woman, man could not be called man; without man, woman could not be named woman. Thus woman is the work of man, while man is a sight full of consolation for woman. Neither of them could henceforth live without the other. Man is in this connection an indication of the Godhead while woman is an indication of the humanity of God's Son.

Hildegard communicated with popes such as Eugene III and Anastasius IV, statesmen such as Abbot Suger, German emperors such as Frederick I Barbarossa, and other notable figures such as Saint Bernard of Clairvaux, who advanced her work, at the behest of her abbot, Kuno, at the Synod of Trier in 1147 and 1148. Hildegard of Bingen’s correspondence with many people is an important element of her literary work because this is where we can see her speaking most directly to us.

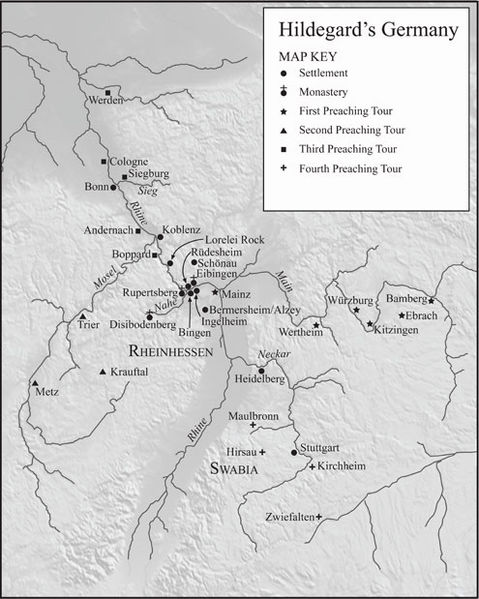

Many abbots and abbesses asked her for prayers and opinions on various matters. She traveled widely during her four preaching tours. She had several rather fanatic followers, including Guibert of Gembloux, who wrote frequently to Hildegard and eventually became her secretary after Volmar died in 1173. In addition, Hildegard influenced several monastic women of her time and the centuries that followed; in particular, she engaged in correspondence with another nearby visionary, Elisabeth of Schönau.

Contributing to Christian European rhetorical traditions, she “authorized herself as a theologian” through alternative rhetorical arts. Hildegard was creative in her interpretation of theology. She believed that her monastery should not allow novices who were from a different class than nobility because it put them in an inferior position. She also stated that ‘woman may be made from man, but no man can be made without a woman’. Due to church limitation on public, discursive rhetoric, the medieval rhetorical arts included: preaching, letter writing, poetry, and the encyclopedic tradition. Hildegard’s participation in these arts speaks to her significance as a female rhetorician, transcending bans on women’s social participation and interpretation of scriptures. The acceptance of public preaching by a woman, even a well connected abbess and acknowledged prophet does not fit the usual stereotype of this time. She conducted four preaching tours throughout Germany, speaking to both clergy and laity in chapter houses and in public, mainly denouncing clerical corruption and calling for reform. Maddocks claims that it is likely she learned simple Latin, and the tenets of the Christian faith, but was not instructed in the Seven Liberal Arts, which formed the basis of all education for the learned classes in the Middle Ages: the Trivium of grammar, dialectic, and rhetoric plus the Quadrivium of arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and music. The correspondence she kept with the outside world both spiritual and social transgressed the cloister as a space of female confinement, and served to document Hildegard’s grand style and strict formatting of medieval letter writing. Recent scholars have asserted that Hildegard made a close association between music and the female body in her musical compositions. The poetry and music of Hildegard’s Symphonia is concerned with the anatomy of female desire thus described as Sapphonic, or pertaining to Sappho, connecting her to a history of female rhetoricians.

In recent years, Hildegard has become of particular interest to feminist scholars. Her reference to herself as a member of the "weaker sex" and her rather constant belittling of women, though at first seemingly problematic, must be considered within the context of the patriarchal church hierarchy. Hildegard frequently referred to herself as an unlearned woman, completely incapable of Biblical exegesis. Such a statement on her part, however, worked to her advantage because it made her statements that all of her writings and music came from visions of the Divine more believable, therefore giving Hildegard the authority to speak in a time and place where few women were permitted a voice. Hildegard used her voice to condemn church practices she disagreed with, in particular simony.

Hildegard has also become a figure of reverence within the contemporary New Age movement, mostly due to her holistic and natural view of healing, as well as her status as a mystic. She was the inspiration for Dr. Gottfried Hertzka's "Hildegard - Medicine", and is the namesake for June Boyce - Tillman's Hildegard Network, a healing center that focuses on a holistic approach to wellness and brings together people interested in exploring the links between spirituality, the arts, and healing,. Hildegard's reincarnation has been debated since 1924 when Austrian mystic Rudolf Steiner lectured that a nun of her description was the past life of Russian poet Vladimir Soloviev, whose Sophianic visions are often compared to Hildegard. Sophiologist Robert Powell writes that hermetic astrology proves the match, and artist mystic Carl Schroeder claims to be in the lineage of Hildegard with the support and validation of reincarnation author Walter Semkiw.

Before Hildegard’s death, a problem arose with the clergy of Mainz. A man buried in Rupertsburg had died after excommunication from the Church. Therefore, the clergy wanted to remove his body from the sacred ground. Hildegard did not accept this idea, replying that it was a sin and that the man had been reconciled to the church at the time of his death. On 17 September 1179, when Hildegard died, her sisters claimed they saw two streams of light appear in the skies and cross over the room where she was dying.

Hildegard was one of the first persons for whom the canonization process was officially applied, but the process took so long that four attempts at canonization were not completed, and she remained at the level of her beatification. Hildegard's name was nonetheless taken up in the Roman Martyrology at the end of the sixteenth century. Her feast day is 17 September. Numerous popes have referred to Hildegard as a saint, including Pope John Paul II and Pope Benedict XVI. Hildegard’s Parish and Pilgrimage Church house the relics of Hildegard, including an altar encasing her remains, in Eibingen near Rüdesheim.

Hildegard of Bingen also appears in the calendar of saints in various Anglican churches. In the Church of England she is commemorated on 17 September.

In space, she is commemorated by the asteroid 898 Hildegard.