<Back to Index>

- Philosopher Protagoras (Πρωταγόρας), 490 B.C.

PAGE SPONSOR

Protagoras (Greek: Πρωταγόρας) (ca. 490 BC – 420 BC) was a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher and is numbered as one of the sophists by Plato. In his dialogue Protagoras, Plato credits him with having invented the role of the professional sophist or teacher of virtue. He is also believed to have created a major controversy during ancient times through his statement that man is the measure of all things. This idea was very revolutionary for the time and contrasting to other philosophical doctrines that claimed the universe was based on something objective, outside the human influence.

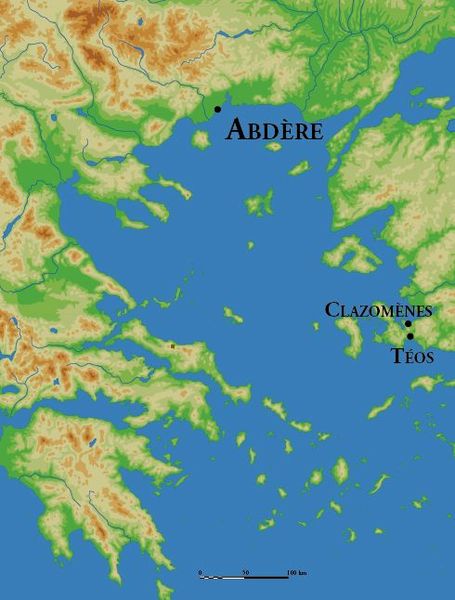

Protagoras was born in Abdera, Thrace, in Ancient Greece. According to Aulus Gellius, he originally made his living as a porter, but one day he was seen by the philosopher Democritus carrying a load of small pieces of wood tied with a short cord. Democritus discovered that Protagoras had tied the load himself with such perfect geometric accuracy that it revealed him to be a mathematics prodigy. He immediately took him into his own household and taught him philosophy.

In Plato's Protagoras, before the company of Socrates, Prodicus, and Hippias, he states that he is old enough to be the father of any of them. This suggests a date of not later than 490 BC. In the Meno he is said to have died at about the age of 70 after 40 years as a practicing Sophist. His death, then, may be assumed to have occurred circa 420. He was well known in Athens and became a friend of Pericles.

Plutarch relates

a story in which the two spend a whole day discussing an interesting

point of legal responsibility, that probably involved a more philosophical question of causation: "In

an athletic contest a man had been accidentally hit and killed with a

javelin. Was his death to be attributed to the javelin itself, to the

man who threw it, or to the authorities responsible for the conduct of

the games?"

Protagoras was also renowned as a teacher who addressed subjects connected to virtue and political life. He was especially involved in the question of whether virtue could be taught, a commonplace issue of 5th Century BC Greece (and related to modern readers through Plato's dialogue). Rather than educators who offered specific, practical training in rhetoric or public speaking, Protagoras attempted to formulate a reasoned understanding, on a very general level, of a wide range of human phenomena (for example, language and education). He also seems to have had an interest in the correct use of words (a topic more strongly associated with his fellow sophist Prodicus).

His most famous saying is: "Man is the measure of all things: of things which are, that they are, and of things which are not, that they are not". Like many fragments of the Presocratics, this phrase has been passed down to us without any context, and its meaning is open to interpretation. However, the use of the word "χρήματα" instead of the general word "ὄντα" (entities) signifies that Protagoras was referring to things that are used by or in some way related to humans. This makes a great difference in the meaning of his aphorism. Properties, social entities, ideas, feelings, judgements, etc. are certainly "χρήματα" and hence originate in the human mind. However, Protagoras has never suggested that man must be the measure of the motion of the stars, the growing of plants or the activity of volcanos. Such views (together with his views about the gods) were considered subversive by the contemporary political elites. Like many modern thinkers, Plato ascribes relativism to Protagoras and uses his predecessor's teachings as a foil for his own commitment to objective and transcendent realities and values particularly those that relate to his aristocratic background. His major effort (through the words of Socrates) is to convince his contemporaries that virtue ("ἀρετή") is a present from the gods, which one either has or has not and that no sophist can teach virtue to people that do not already possess it. Plato ascribes to Protagoras an early form of phenomenalism, in which what is or appears for a single individual is true or real for that individual. However, as it is clearly presented in the dialogue "Theaetetus", Protagoras explains that some of such controversial views may result from an ill body or mind. He stresses that although all views may appear equally true (and perhaps should be equally respected) they are certainly not of equal gravity. One may be useful and advantageous to the person that has it while another may prove harmful. Hence, the sophist is there to teach the student how to discriminate between them, i.e. to teach virtue.

Protagoras was a proponent of agnosticism. In his lost work, On the Gods, he wrote: "Concerning the gods, I have no means of knowing whether they exist or not or of what sort they may be, because of the obscurity of the subject, and the brevity of human life."

Very few fragments from Protagoras have survived, though he is known to have written several different works: Antilogiae and Truth. The latter is cited by Plato, and was known alternatively as 'The Throws' (a wrestling term referring to the attempt to floor an opponent). It began with the "man the measure" pronouncement. The crater Protagoras on the Moon is named in his honor.

According to Diogenes Laërtius, the above outspoken agnostic position taken by Protagoras aroused anger, causing the Athenians to expel him from the city, and all copies of the book were collected and burned in the marketplace; this is also mentioned by Cicero. However, the Classicist John Burnet doubts this account, as both Diogenes Laertius and Cicero wrote hundreds of years later and no such persecution of Protagoras is mentioned by contemporaries who make extensive references to this philosopher. Burnet notes that even if some copies of Protagoras' book were burned, enough of them survived to be known and discussed in the following century.